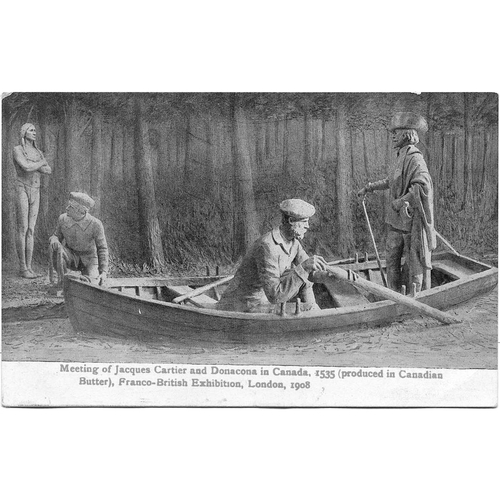

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DONNACONA, chief of Stadacona until May 1536, taken into exile by Jacques Cartier along with two sons (Domagaya and Taignoagny); d. in France probably in 1539.

In July 1534, in Gaspé Bay (“la baie d’Honguedo”), Jacques Cartier entered into relations with Indians who had come from Stadacona (Quebec) to fish. When Cartier erected a cross there 24 July 1534, their chief, Donnacona, felt that he had been wronged; he harangued the French; his canoe was seized and he was forced to go aboard the ship along with those who were accompanying him. Cartier feasted him and persuaded him to let his two sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, sail away with him, promising to bring them back. The French needed to train interpreters. Donnacona accepted and his two sons left for France. They spent eight months there and sailed again with Cartier 19 May 1535, without, however, having been baptized. They had learned French, they were able to give valuable information about their country; thanks to them, Cartier discovered in 1535 the great river which he had missed the previous year. Under the guidance of his two interpreters Cartier sailed up the river and took “the route to Canada”; on 7 September the interpreters finally arrived home, in “the province of Canada.”

At this point Cartier, who was attracted by the hypothesis of a route to Asia, wanted to go on, to reach Hochelaga; from then on the interpreters began to intrigue against the French; Taignoagny in particular, we are told, “was intent on nothing but treason and malice.” To dissuade Cartier from making this voyage they put on for him a scene of sorcery, which had no effect; Donnacona vainly offered gifts. Cartier left for Hochelaga without his interpreters. On his return, he found that his allies were no longer to be relied upon; he built fortifications. The chief of Achelacy (in the neighbourhood of Portneuf) put him on his guard against Donnacona and his sons: having become familiar with business practice in France, Domagaya and Taignoagny took their kinsmen to task for accepting trifling articles of no value in return for their goods, and Stadacona became more demanding. Relations were even broken off for a time; they were renewed 5 November, with the greatest benefit to the French. Indeed, Cartier obtained from Donnacona, who claimed to have travelled a great deal, much information about the country and also about the fabulous kingdom of the Saguenay which could be reached by the river which bears that name today and where “there are immense quantities of gold, rubies and other rich things, and . . . the men there are white as in France and go clothed in woolens,” along with many other “marvels too long to relate.” In addition, during the winter, when scurvy was ravaging the little French colony, it was Domagaya who unwittingly saved the day; Cartier learned from him by ruse the secret of the infusion of annedda (white cedar).

The mutual distrust flared up again in the spring of 1536: Donnacona absented himself mysteriously and returned with people who had never been seen before; Cartier sent him an embassy, but Donnacona refused to receive it. It was finally learned that a quarrel had broken out at Stadacona between Chief Donnacona and his rival Agona. The interpreter Taignoagny asked for Cartier’s help to eliminate Agona; for the French it involved carrying Agona off into exile. Cartier saw how he could turn the situation to good account and was “determined to outwit them.” Since there was a crisis at Stadacona, it was better to get rid of Donnacona and his sons who were hindering the policy of the French; and, another advantage in carrying Donnacona off to France, the chief could recount personally all he knew to François I. Cartier pretended therefore to join in the plot against Agona; the interpreters promised to come back the following day for the feast of the Holy Cross (3 May). Donnacona and his people arrived for the religious ceremony, albeit very distrustfully; upon an order from Cartier, Chief Donnacona, his two sons, and two other headmen were seized, The inhabitants of Stadacona were upset; Cartier assured them (“and spoke thus to set their minds at rest”) that Donnacona would come back in 12 moons, laden with gifts, after describing to the king the marvels of the Saguenay. On 6 May 1536 he left Stadacona with ten Iroquois on board: old Donnacona, his sons Domagaya and Taignoagny, a little girl of ten or 12 years of age, and two little boys whom Cartier had received as gifts the preceding autumn, a little girl of eight or nine years of age whom the chief of Achelacy had given him, and three other Indians. The way was clear for Agona.

It was not until 23 Aug. 1541 that Cartier arrived again at Stadacona; he returned without the Indians whom he had captured five years earlier. He announced to Agona, who was still chief of Stadacona, that Donnacona had died in France, that the others were living there as great lords, and that they were married and had not wished to come back: all of which naturally did not cause Chief Agona any grief.

In reality, of the ten Iroquois nine were dead; there remained only one little girl whose fate is unknown. Upon their arrival at Saint-Malo 16 July 1536, Chief Donnacona and his companions proceeded to live at the king’s expense. Donnacona accepted questioning, even before a notary, about what he had seen on his voyages; the monk and historian André Thevet, who specialized in interrogating travellers, claimed that he had had a long conversation with Donnacona. The old chief was presented to François I: he talked to him about mines which were very rich in gold and silver, of an abundance of cloves, nutmeg, and pepper (the spices of which Europe dreamed); he enumerated many marvels, such as men with wings on their arms like bats, who flew from the trees to the ground. François I was very enthusiastic; someone said to him that the Indian chief was perhaps relating all this simply in order to obtain the opportunity of returning home; but the king in reply insisted upon Donnacona’s veracity. On 25 March 1539 three of the Indians whom Cartier had brought back were baptized; the register does not identify them, we know only that they were males. Perhaps they were baptisms in articulo mortis? It was in any event towards this time that Donnacona, according to Thevet, died a Christian; and except for the little girl of ten years of age, his companions died about the same time.

When Cartier returned in 1541, Agona was then the only chief remaining at Stadacona. Franco-Iroquois relations were not improved thereby: Cartier’s second voyage to Hochelaga (again without interpreters) undoubtedly had some bearing upon this, as did Agona’s fear of suffering Donnacona’s fate; even the chief of Achelacy, long faithful to Cartier, turned against the French. A veritable war finally broke out between the Indians of Stadacona and the colonists at Charlesbourg-Royal (at Cap-Rouge, near Quebec); the Indians were to boast of killing more than 35 of Cartier’s men.

Agona was avenging Donnacona. We must go back to this wintering-over of 1541–42 to date the beginning of the wars between the French and the Iroquois. They were the result of Cartier’s policy.

Biggar, Documents relating to Cartier and Roberval, 69–70, 75–82, 128, 456–57, 463. Hakluyt, Principal navigations (1903–5), VIII, 283–90 (English version of Cartier’s third voyage). André Thevet, Les singularitez de la France antarctique, autrement nommée Amérique: & de plusieurs terres & isles découvertes de nostre temps, éd. Paul Gaffarel (Paris, 1878), 407. Voyages de Jacques Cartier au Canada, éd, Th. Beauchesne in Les Français en Amérique (Julien), 77–197. Voyages of Cartier (Biggar). A. G. Bailey, “The significance of the identity and disappearance of the Laurentian Iroquois,” RSCT, 3d ser., XXVIII (1933), sect.ii, 97–108. Hoffman, Cabot to Cartier, 131–60, 197–215. W. D. Lighthall, “Hochelagans and Mohawks; a link in Iroquois history,” RSCT, 2d ser., V (1899), sect.ii, 199–211. Jacques Rousseau, “L’annedda et l’arbre de vie,” RHAF, VIII (1954), 171–201; “Ces gens qu’on dit sauvages,” Cahiers des Dix, XXIII (1958), 71; “Le mystère de l’annedda,” in Jacques Cartier et “la grosse maladie” (XIXe Congrès international de Physiologie Pub., Montréal, 1953), 105–16.

Cite This Article

Marcel Trudel, “DONNACONA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/donnacona_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/donnacona_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marcel Trudel |

| Title of Article: | DONNACONA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |