Source: Link

DOBBS, HARRIET (Cartwright), humanitarian and artist; b. 27 Aug. 1808 in Dublin (Republic of Ireland), daughter of Maria Sophia and Conway Edward Dobbs, qc; m. 21 Nov. 1832 in Dublin the Reverend Robert David Cartwright, son of Richard Cartwright* of Kingston, Upper Canada, and they had one daughter and four sons, including Sir Richard John Cartwright*; d. 14 May 1887 at Portsmouth (now part of Kingston).

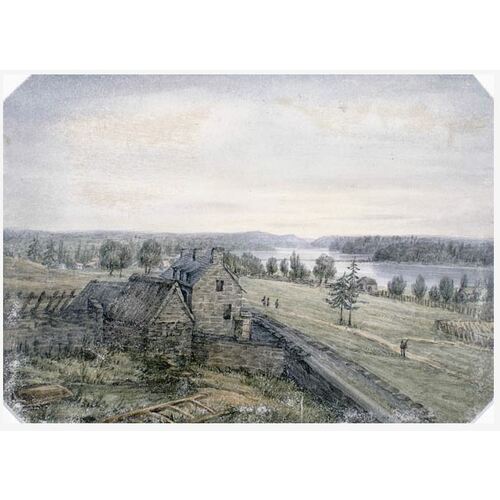

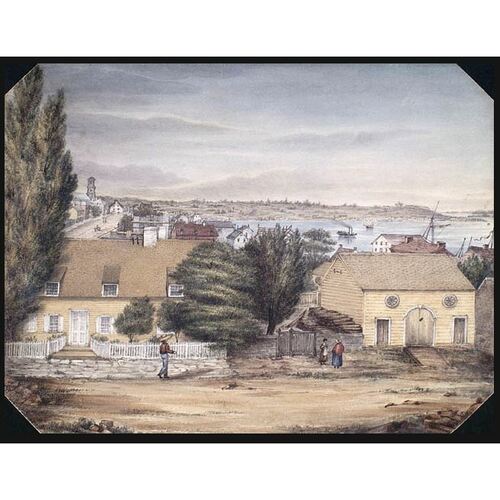

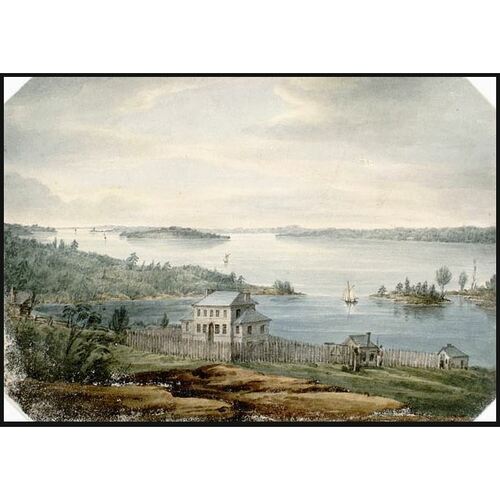

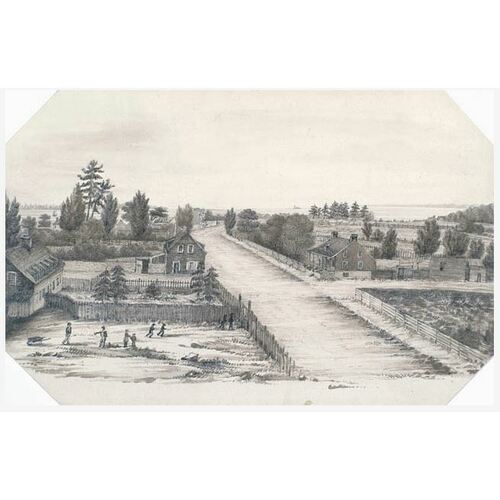

Harriet Dobbs grew up in Ireland as one of eight children in an upper class, religious family. She received a good education including drawing lessons which encouraged her considerable talent for sketching and painting. She sketched daily in Ireland and produced drawings, water-colours, and “likenesses” after she came to Canada.

On 5 June 1833 Harriet arrived in Kingston with her husband as the newest member of one of the town’s founding families. Shortly after entering the new stone mansion that was to be her home she received the élite of Kingston who came to welcome her in “the ceremony of cake and wine . . . a Canadian custom it seems.” In addition to the status of the family in the community, her husband’s position as assistant minister to Archdeacon George Okill Stuart* at St George’s Church encouraged her inclination towards charitable work.

Harriet immediately joined the Female Benevolent Society, an interdenominational group of women who since 1820 had been providing, in an abandoned blockhouse, the only hospital care for the poor in Kingston. The hospital, actually a hostel for the sick and their families, opened in November and closed in May each year. During the summer the remaining patients were placed in boarding-houses. Harriet Cartwright, as one of the managers of the society, took her turn in a rotation system, being responsible for the management of the hospital for a week at a time.

To raise badly needed funds for the society she organized a sewing group in December 1833, acting as secretary for the ladies who produced items for sale at an annual bazaar. She also painted “likenesses” to raise funds for charity. Not satisfied with just the physical care of the poor, in April 1834 she organized the first FBS school in a room attached to the hospital. Classes ceased later that year when she was forced to limit her charitable activities because of the birth of her first child and the care required by her ailing husband. After the blockhouse hospital burned in December 1835, the society became dormant, expecting a general hospital to be opened in the new building constructed for that purpose.

In 1839 Harriet Cartwright reorganized the FBS as “a society for giving out work to employ the poor . . . by directing industry into the right channels.” The members collected funds, appointed visitors, purchased sewing and knitting materials, and distributed work to the unemployed and to fatherless families. The finished products were given to the poor or sold at the annual bazaar. With the materials the society also handed out advice and dire warnings about “the evil of strong drink.”

In 1840 the FBS took an activist role in the fight for temperance, which was very unusual for women’s groups at that time, especially in Canada. Harriet wrote that the society “ventured so far out of place as to get up a petition to the magistrates to diminish the licenses and look after the unlicensed dram shops abounding in every quarter.” A waterfront fire in Kingston in April 1840 had burned 14 taverns on one block and the petition succeeded in bringing about a limit on the number of liquor licences issued. In November Harriet wrote that the FBS had “had some effect.” Late that year Harriet also organized a Church of England district visiting society to investigate cases of distress and “to create a more friendly intercourse with those in the lower class, who often feel themselves overlooked & neglected by their superiors.” The men of St George’s visited in the district, the women visited in the town.

The general hospital, expected to commence in 1835, never opened and the FBS began a temporary hospital again late in 1842, this time in an old warehouse. Harriet’s time, however, was spent caring for her sick husband who died 24 May 1843. After a short visit to Ireland with her four children, Harriet returned to her work in Kingston. In November 1845 the society opened two wards in the hospital building, which had been vacated by the parliament, and Harriet Cartwright’s name headed the list of “visitors” who took responsibility for running the hospital. Its operation became too expensive and time-consuming for the FBS and after 1846 they were assisted by a male volunteer committee until the hospital was incorporated under municipal management in 1849 [see Horatio Yates].

During this time as frequent epidemics, especially the typhus epidemic of 1847, left more widows and orphans in Kingston, the FBS formed the Widows’ and Orphans’ Friends Society. Harriet Cartwright was the secretary, and the society concentrated on providing shelter for unfortunates. A house of industry, opened in 1847 and assisted by city funds after 1852, provided accommodation for widows but not for orphans. The society was reorganized and in 1856 the Orphans’ Home and Widows’ Friend Society, incorporated in 1862, began to concentrate on providing a home for “destitute orphans and homeless children.” In February 1857 the ladies bought a small house, and architect William Coverdale* donated the plans for a dormitory and school building. The “ladies’ school” which had been held at the house of industry from 1848 moved to the home in 1857. The salaries of the teachers were paid by the trustees of the common schools, and 70 orphans and children from destitute families were enrolled.

For 31 years Harriet served as corresponding secretary of the Orphans’ Home and Widows’ Friend Society. She sought funds from business and government as well as by personally canvassing homes in the village of Portsmouth, where she had moved after her return from Ireland. She interviewed prospective employers, adoptive parents, and the fathers of abandoned children, and as well investigated apprentice bonds and working conditions of the wards of the FBS. A new orphans’ home was opened in 1863; in her final years Harriet was planning to establish a kindergarten.

As a manager of the FBS Harriet was also involved in the care of women in the provincial penitentiary, which had opened in 1835. Dr James Sampson*, surgeon at the penitentiary and the Cartwrights’ family physician, persuaded her to be one of the first regular visitors to the prison. She was especially troubled by the incarceration of mentally ill women for whom there was no other institution until the Rockwood Asylum was opened in 1856. She also assisted her brother, the Reverend Francis William Dobbs, who was chaplain at the penitentiary after 1875, in organizing Christmas parties for women prisoners.

Harriet Cartwright faced the sorrows of her life, the death of her first son at 14 months and her husband’s death after 11 years of marriage, as “deserved chastisement” to be accepted “with a truly humble heart.” She typified the spirit of Victorian humanitarianism and her obituary in the Daily Whig of Kingston said: “She was a good old lady, full of piety and much given to good work and her reward is certain.”

The letterbook of Harriet Dobbs (Cartwright) is in the possession of her descendants and some of her sketches are held at the PAC.

Canadian Penitentiary Service Museum, Arch. Section (Kingston, Ont.), Kingston Penitentiary, Inspector’s letterbook, 23 April 1835–1 May 1866; Warden’s letterbook, 2 Aug. 1834–8 Sept. 1843. QUA, Cartwright family papers, H. D. Cartwright, letters, 1832–43 (transcripts); House of Industry records; Orphans’ Home and Widows’ Friend Society records. Daily British Whig, 16 May 1887. Daily News (Kingston), 5 Sept. 1856, 20 April 1857. Kingston Spectator, 22 Jan. 1833. M. I. Campbell, 100 years: Orphans Home and Widows Friend Society, 1857–1957 ([Kingston, 1957?]). J. D. Stewart and I. E. Wilson, Heritage Kingston (Kingston, 1973). Margaret Angus, “A gentlewoman in early Kingston,” Historic Kingston, no.24 (1976): 73–85. H. L. Cartwright, “The Cartwrights of Kingston,” Historic Kingston, no.16 (1968): 41–47.

Cite This Article

Margaret Sharp Angus, “DOBBS, HARRIET (Cartwright),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dobbs_harriet_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dobbs_harriet_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret Sharp Angus |

| Title of Article: | DOBBS, HARRIET (Cartwright) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |