Source: Link

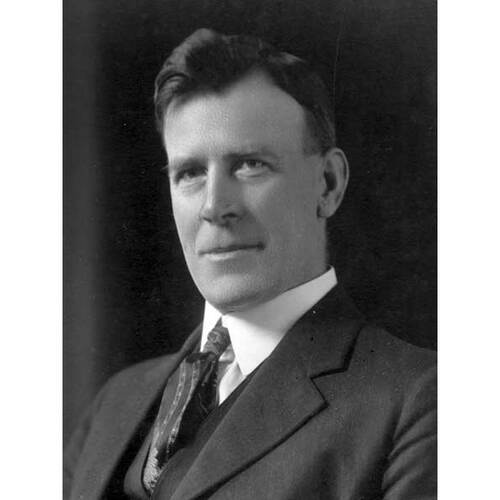

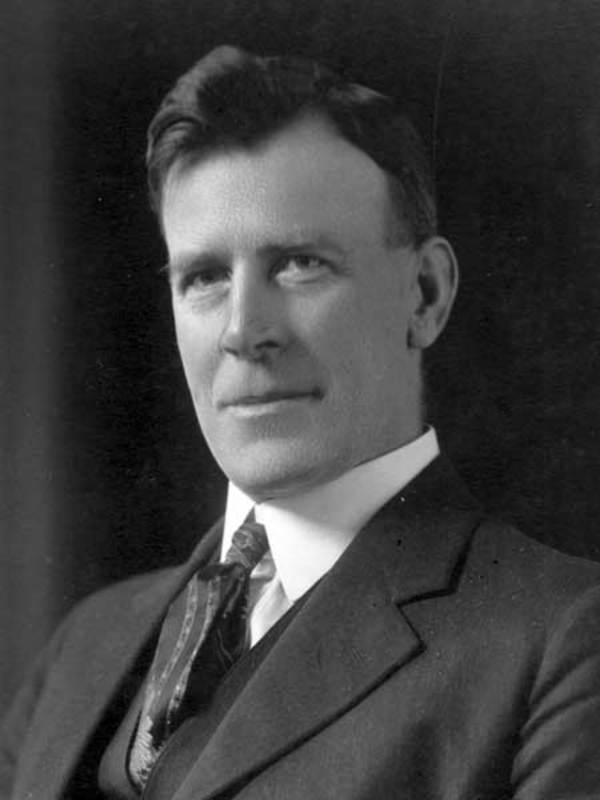

DIXON, Frederick John, labourer, designer, social reformer, lecturer, politician, office holder, and insurance salesman; b. 20 Jan. 1881 in Englefield, England, son of Thomas Dixon and Hannah More; m. 15 Oct 1914 Winona Margaret Flett* in Winnipeg, and they had three children, two of whom died before reaching adulthood; d. 18 March 1931 in Fort Garry (Winnipeg) and was buried in Brookside Cemetery, Winnipeg.

Fred Dixon was born on an estate near Reading, west of London, to a rural labouring family. Little is known of his early life. He apprenticed as a gardener, but finding himself unemployed he followed his elder brother George to Manitoba in 1904. Initially his fortunes fared little better in Canada and he turned to various jobs, including farm labourer and pick-and-shovel worker. He took a correspondence course in drafting to improve his drawing skills, and obtained a full-time position as a designer in the Winnipeg office of Bemis Brothers Bag Company, a packaging firm.

As a result of the wheat boom, Edwardian Winnipeg experienced both the problems and the promises of unrestrained growth. Not surprisingly, the city was a hothouse of reform ideas and social movements. Dixon gravitated to a circle of reformers who met above the bookstore of Robert Max Mobius, a naturopath, phrenologist, and, most important for Dixon, an advocate of the single tax. The single tax movement had developed from the ideas of American social critic Henry George, whose theories had been publicized in Canada by, among others, John Wilson Bengough* and Thomas Phillips Thompson. George believed that the growing poverty in wealthy societies was caused by private ownership of land. Unequal access to land meant that when social processes such as population growth increased the value of property, a privileged few benefited from the unearned increment, while others were driven into penury.

In the hands of Dixon and his close colleagues, including reformer Seymour James Farmer*, the Georgite philosophy was both all-encompassing and surprisingly narrow. A single tax on land values, it was thought, would act as a panacea, curing an array of social problems. The achievement of this goal required fighting against the Canadian tariff, which unfairly enriched those with the power to convince government to protect their interests, and pressing for direct legislation that would allow citizens to initiate laws and recall politicians, thus breaking the hold that established parties had on government. This democratic agenda was consistent with those proposed by other movements that attracted Dixon, particularly women’s suffrage and workers’ rights. Yet, at the same time, his defence of free trade implied an economic liberalism that separated him from the socialists. This distinction was significant. Throughout his political life Dixon would associate closely with the Trades and Labour Council of Winnipeg and with local labour parties, but he remained a strong believer in individual rights and freedoms. For example, in 1908, during an attempt by the newly created Independent Labor Party to define its platform, Dixon headed the group opposed to the inclusion of a plank on collective ownership of the means of mass production, and the party ultimately split.

Over the next ten years Dixon contributed a regular column entitled “Land values” to Arthur W. Puttee*’s Voice (Winnipeg), a labour newspaper. Through articles he frequently published in the Grain Growers’ Guide (Winnipeg), he probably reached a wider, rural audience. He led in the creation of the Single Tax League of Manitoba in 1909, and was active in a range of reform organizations that cut across class lines, including the Manitoba Health League, founded in 1907, and the Manitoba Federation for Direct Legislation, for which he worked as a paid organizer from February 1911 to 1914. He was also involved in the province’s main women’s suffrage group, the Political Equality League, and he married another prominent member, Winona Flett, in 1914.

In 1910 Puttee had called Dixon the Winnipeg labour movement’s “most forceful, fearless and logical speaker.” His considerable oratorical abilities and activism led to his nomination by the short-lived Manitoba Labor Party as its candidate in the provincial election of June 1910 for the riding of Winnipeg Centre. He lost to Conservative Thomas William Taylor by only 73 ballots. Four years later, describing himself as an “independent progressive,” he ran in the election of 10 July and won by a large majority. Both campaigns were aimed at a broad spectrum of voters. Dixon’s platform in 1914 had been, for the most part, little different from that of the increasingly reform-minded Liberals under Tobias Crawford Norris. As an mla, he played an important part in exposing the corruption surrounding the construction of the new provincial legislative building [see Victor William Horwood] that brought down the Conservative government of Sir Rodmond Palen Roblin and led to a Liberal victory in the contest of August 1915 and his own re-election. On the issues dearest to Dixon’s perception of direct democracy, there were mixed results under Norris’s Liberals. The Initiative and Referendum Act of 1916 allowed citizens to propose legislation and force referenda on the assembly, but it would ultimately be declared ultra vires by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Dixon’s advocacy of female suffrage proved more successful; the Norris government granted women the right to vote in 1916.

Dixon could be distinguished from the Norris Liberals principally by his views on military conflict. Well before World War I began, he had loudly denounced the spirit of militarism that he saw pervading both the federal Conservative and Liberal parties. In the provincial election of 1914 he had specifically pilloried Roblin’s “flag-flapping.” Compulsory military service especially offended him. He quickly became an important spokesperson of the TLC’s campaign at the end of 1916 against the registration of workers required by the establishment of the National Service Board, urging them not to sign their registration cards and declaring his own willingness to go to jail over the issue.

Dixon’s anti-war pronouncements provoked a national storm. Norris declared that opponents of registration should be imprisoned. Dixon’s alleged “pro-Germanism” was denounced by editors of the city’s newspapers (including John Wesley Dafoe* of the Manitoba Free Press), the Winnipeg Board of Trade, and the Winnipeg Ministerial Association. About 2,000 people crammed the Thomas Scott Memorial Orange Hall on 30 Jan. 1917 to protest against his comments. But there were limits to wartime jingoism in the province. The Manitoba Grain Growers’ Association received him enthusiastically despite threats that its convention in Brandon would be disrupted. Dixon’s opponents tried to turn his dearly loved instruments of direct democracy against him. They circulated a petition demanding his recall from the legislature and the removal from Winnipeg Centre of the “stigma of a seditious constituency.” Although the petition had no legal standing, Dixon promised to resign if it received the support of 25 per cent or more of the electors in his riding. The Manitoba Free Press claimed that “everyone” was signing it except “foreigners,” yet presentation was repeatedly delayed – the Winnipeg Telegram joked that it would still be circulating in 1927. In the end, the attempt to unseat Dixon failed.

By 1918 the existence of reinvigorated labour and farmer groups led Dixon to try to create in Manitoba a united movement of “wealth producers,” a Non-Partisan League on the models of those in North Dakota and Alberta. In June he wrote to approximately 100 potential members, but little came of the effort. He then focused on the new Dominion Labor Party, the provincial wing of the Canadian Labor Party, becoming its chairman in the winter of 1918–19. Closely tied to the unions, the DLP also reflected his passions, adopting a reconstruction program that called for a single tax on property.

After the war the city headed towards the great conflagration of the Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowiski*]. Despite Dixon’s lack of trade-union credentials, his sense of justice and personal courage led him directly into the fray. At the now-famous meeting held on 22 Dec. 1918 at the Walker Theatre, he called for the release of political prisoners, such as so-called enemy aliens and conscientious objectors. The meeting, sponsored by the TLC and the Socialist Party of Canada, and featuring the city’s most prominent labour and socialist speakers, demonstrated the growing identification of the workers with international revolutionary movements as well as the convergence of trade-unionist and socialist forces. When the strike broke out the following May, he supported it from the floor of the Legislative Assembly. He and his close friend James Shaver Woodsworth* took over the TLC’s Western Labor News (Winnipeg) when its editor, William Ivens*, and other strike leaders were arrested on 16 June. A week later Woodsworth was arrested and the paper was forcibly suppressed. Dixon went into hiding but continued to publish it, first on 24 June as a special edition of the Western Star and on the next two days as the Enlightener. When Ivens was let out on bail, Dixon turned himself in, was briefly imprisoned, and then released on 28 June.

Dixon’s trial for seditious libel, held from 29 Jan. to 16 Feb. 1920, became a cause célèbre. Although coached by the notable jurists Lewis St George Stubbs and Edward James McMurray, he chose to defend himself. At issue was his speech at the Walker Theatre and others, as well as three articles. “Kaiserism in Canada” and “Bloody Saturday” had assailed the brutality with which the authorities had attacked the “silent parade” of returned soldiers on 21 June 1919, while his “Alas! The poor alien,” seized before it could be printed, deplored the treatment of foreign-born strikers who had been arrested. In a masterful closing address, he focused on liberty of speech and of the press. He was acquitted and the crown decided to drop similar charges against Woodsworth. Dixon had his hands full during the trial. Each day he raced from the courtroom to the legislative assembly, where he pressed the Norris government to reveal who was paying for the prosecution of the strike leaders; in his case, it was the provincial attorney-general. After the strike he undertook a lecture tour with Woodsworth to raise money for the defence of those accused.

Dixon’s personal popularity, reflected in the results of the provincial election of 29 June 1920, was astounding. Winnipeg City was a single, ten-member constituency. He came first among 41 contestants, with almost three times as many votes as Attorney General Thomas Herman Johnson*, the second-place candidate. Despite deep social divisions in post-strike Winnipeg, he had won 101 of the city’s 135 polls. He took his place at the head of the 11-member Labour caucus. The years following the strike proved difficult for his brand of liberalism. The city’s labour movement was deeply divided between the increasingly conservative TLC and the new, more radical One Big Union. In order to distance themselves from these battles, some moderate Labourites, former strike leaders, and heads of special-interest groups joined to form the Independent Labor Party in November 1920 with Dixon as their chief. The new party met with a certain amount of success, electing provincial and federal representatives.

Although re-elected in July 1922 as the first of the 43 candidates in his riding, Dixon was soon overwhelmed by personal tragedy. The death in 1920 of his son, aged two, followed by those of his wife in 1922 and his nine-year-old daughter and his mother-in-law (who had helped to care for the children) in 1924, sapped his morale. He resigned from the legislature in July 1923 because of skin cancer and underwent numerous treatments. He had been a part-time insurance salesman for the Confederation Life Assurance Company since 1919 and now worked on a full-time basis when his health permitted it. His only return to public life was to serve from November 1927 to early 1928 on a provincial commission examining seasonal unemployment. One of the commission’s recommendations was the creation of a national unemployment insurance plan. He died in March 1931.

Three decades later, Frederick George Tipping, a colleague from the days of the general strike, remembered Dixon as “without doubt the most popular man in public life that Winnipeg has ever had.” An individual of wide reading and broad experience, Dixon possessed oratorical skills and a passion for justice that made him a leading figure of the formidable reform tradition that emerged in Winnipeg during the years before World War I. His career also testifies to the extent that democracy had become a class issue; Dixon chose to stand beside Winnipeg’s workers in the epic struggles of 1919.

Frederick John Dixon’s impressive speech during his trial for seditious libel was published as Dixon’s address to the jury in defence of freedom of speech, considered the most powerful address ever delivered in the courts of Manitoba, and Judge Galt’s charge to the jury in “Rex v. Dixon” (Winnipeg, [1920]).

AM, MG 14, B25 (Frederick John Dixon papers); P5607 (Jack Samuel Walker papers). Man., Dept. of Tourism, Culture, Heritage, Sport and Consumer Protection, Vital statistics agency (Winnipeg), nos.1914-134063, 1931-019331. National Arch. (G.B.), RG 11/1299, f.110, p.14; RG 12/989, f.69, p.5; RG 13/1156, f.45, p.14. Manitoba Free Press, 1912–31. Voice (Winnipeg), 1907–18. Western Labor News (Winnipeg), 1918–21. Winnipeg Telegram, 20 March 1917. CPG, 1910–31. Harry and Mildred Gutkin, Profiles in dissent: the shaping of radical thought in the Canadian west (Edmonton, 1997). D. N. Irvine, “Reform, war, and industrial crisis in Manitoba: F. J. Dixon and the framework of consensus, 1903–1920” (ma thesis, Univ. of Man., Winnipeg, 1981). Allen Mills, “Single tax, socialism and the Independent Labour Party of Manitoba: the political ideas of F. J. Dixon and S. J. Farmer,” Labour (Halifax), 5 (1980): 33–56. Martin Robin, Radical politics and Canadian labour, 1880–1930 (Kingston, Ont., 1968). R. St G. Stubbs, Prairie portraits (Toronto, 1954). F. [G.] Tipping, “Vote for men in jail,” Canadian Democrat (Winnipeg), 2, no.3 (April–May 1960): 11–15. Winnipeg 1919: the strikers’ own history of the Winnipeg General Strike, ed. Norman Penner (2nd ed., Toronto, 1975).

Cite This Article

James Naylor, “DIXON, FREDERICK JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 23, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dixon_frederick_john_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dixon_frederick_john_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | James Naylor |

| Title of Article: | DIXON, FREDERICK JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2016 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | February 23, 2026 |