CHAUVIN DE TONNETUIT, PIERRE DE, French naval and military captain, lieutenant of New France, called the founder of Tadoussac; b. Dieppe, Normandy; d. early in February 1603 in France (probably at Honfleur). He should not be confused with Capt. Pierre Chauvin de La Pierre, or Chavin, of Dieppe, whom Champlain placed in command at Quebec during his absence in 1609–10.

He was of a wealthy merchant family, and married first Jeanne de Mallemouche, by whom he had one son, François, and second, Marie de Brinon. In 1583 he was serving under admiral Aymar de Chaste in the Azores, and in 1589 he was captain of the important Huguenot garrison at Honfleur, occupied by Du Gua de Monts the previous year. By 1596, as several notarized documents attest (reproduced in Bréard, Documents, 73ff.), Chauvin had developed an interest in commercial and maritime enterprises. He now owned four vessels, the Don-de-Dieu, the Espérance, the Bon-Espoir, and the Saint-Jean, and he was regularly engaged in the fur trade and cod-fishery of Canada and Newfoundland.

A Calvinist, he had given illustrious service in the wars against the League, and was soon rewarded with a position of influence in the new king’s court. At the solicitation of François Gravé Du Pont, who also had made many trading expeditions to the St. Lawrence, Chauvin sought and gained from Henri IV, in 1599, a ten-year monopoly of the fur trade in New France. However, following the protest of La Roche de Mesgouez, who held a similar concession, Henri IV gave Chauvin a new commission on 15 Jan. 1600 which acknowledged only his “being one of the lieutenants” of La Roche.

Chauvin embarked from Honfleur in the early spring of 1600, with his four ships and the intended colonists, and Gravé as his partner and lieutenant. De Monts sailed with them as a passenger. Against the advice of Gravé and de Monts, Chauvin chose Tadoussac as his destination – inevitably, perhaps, for his trading post, but fatally for the colony. Strategically situated at the junction of the Saguenay and St. Lawrence rivers, the Indian trading routes to the interior, with a harbour adjacent, Tadoussac had long been a Montagnais summering place for barter, and for half a century a fur-trading and fishing resort for Europeans. But with the arms they received the Montagnais had ousted the Iroquois from the region; they were soon to be visited by a revenge of equal horror, and driven far into the interior. Tadoussac was to suffer; and as allies of the Montagnais, and soon of the Algonkins and Hurons too, all enemies of the Iroquois, the French and their fur trade were distressed for many years. Furthermore, the area was ill fitted for settlement because of the rugged terrain and poor soil, and because in winter “the cold is so great” Champlain says in his Voyages “that if there is an ounce of cold forty leagues up the river, there will be a pound of it here.”

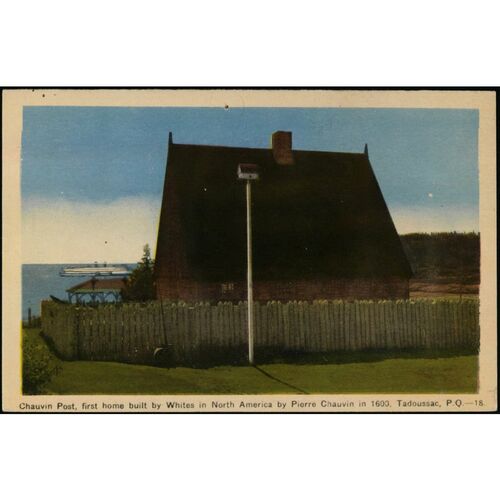

A house was built at Tadoussac, which Champlain saw and described as being “twenty–five feet long by eighteen wide and eight feet high, covered with boards with a fireplace in the middle,” encompassed by a wattle palisade and a ditch. Champlain’s map of Tadoussac in 1608, which appears in the Works (II, 19) depicts this structure on the east bank of a stream which enters the harbour; underneath are the words “abitasion du Cappn chauvain de lan 1600” (habitation of Capt. Chauvin of the year 1600). After the colonists were settled, the monopolists devoted their energies to the traffic in peltry until the autumn, when they sailed for France with a cargo of beaver and other furs. At Tadoussac they left 16 men to face the unknown northern winter; only 5 survived, and these owed their lives to Indian hospitality.

According to contemporary documents Chauvin sent only one vessel, the Espérance, to the Saguenay the following spring (cf. Bréard, Documents, 69–70, 88), but did not sail himself. Doubtless the remnant of his colony returned with this ship in the autumn, and no others were set ashore to repeat the suffering. In April 1602, Chauvin commanded another expedition from Honfleur to New France, this time with only two ships, the Don-de-Dieu and the Espérance, and almost certainly no colonists. After a summer of trading in the Tadoussac region he returned, from this the third voyage of his monopoly, in October 1602. If the number of vessels employed is an indication, Chauvin had won no great success from his privilege.

During half a century the Canadian fur trade had assumed considerable proportions, involving the capital of a great many investors. As with previous French grants of monopoly trading in Canada, Chauvin’s patent was vigorously opposed by the excluded merchants of the French seaports. Henri IV had stood resolute in the larger cause; but after three summers, Chauvin had failed to establish a colony, and his rivals were as clamorous as ever. In 1602, therefore, the monopoly was extended to include certain other traders in Rouen and Saint-Malo, providing they undertook a share of the obligations. When this also failed to silence the outcry for free trade the king summoned a commission of inquiry, on 28 Dec. 1602, to meet in Rouen in a month’s time. Here the commissioners (one of whom was the governor of Dieppe, Aymar de Chaste) received delegates from the Rouen and Saint-Malo merchants, and Chauvin himself, to discuss and arbitrate the monopoly and its colonization terms. An agreement to continue both was apparently reached and published (Biggar, Early trading companies, 45–46), but before the vessels could leave on another voyage, Chauvin died. The monopoly passed to de Chaste who, that same spring, dispatched three ships to New France. One, the Bonne Renommée belonging to de Chaste, was commanded by Gravé, whose task was to survey the resources of the region and find a more auspicious place for settlement; in this he was aided by Champlain, on his first visit to New France.

On 20 Jan. 1603, Chauvin was still living, for he gave a power of attorney to his sister Madeleine; in the absence of any known record we may accept the estimate of Bréard (Documents, 71), based on the evidence, that he died during the first days of February. The same writer shows that Chauvin had probably made a fortune during his lifetime, for he owned four ships and several smaller boats ‘ more than one house, valuable personal property, and he had bought the land of Tonnetuit. Yet, at his death, his estate was so encumbered that both his wife and his son renounced it. Some historians have observed that Chauvin was more concerned with profit than with his colonists; but evidently his last years had only reduced his fortune, and he did send a ship to Tadoussac early in 1601, probably rescuing the surviving colonists, and in all likelihood he never replaced them. History, however, will remember him as the builder at Tadoussac, eight years before Quebec, of the first trading post, the first house, in Canada. A replica, serving as a museum, has been built on what is thought to be the original site.

Champlain, Works (Biggar), II, 19; III, 305–11. Biggar, Early trading companies, 42–46. Bréard, Documents relatifs à la marine normande, 65–92. Gustave Lanctot, Réalisations françaises de Cartier à Montcalm (Montréal, 1951), 45 f. La Roncière, Histoire de la marine française, IV (1923), 318–19. Joseph Le Ber, “Un document inédit sur l’Île de Sable et le Marquis de la Roche,” RHAF, II (1948–49), 203 ff. Trudel, Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, I, 236.

Cite This Article

William F. E. Morley, “CHAUVIN DE TONNETUIT, PIERRE DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chauvin_de_tonnetuit_pierre_de_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chauvin_de_tonnetuit_pierre_de_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | William F. E. Morley |

| Title of Article: | CHAUVIN DE TONNETUIT, PIERRE DE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |

![Chauvin Post, first home built by whites in North America by Pierre Chauvin, in 1600, Tadoussac, P.Q., 18 [image fixe] Original title: Chauvin Post, first home built by whites in North America by Pierre Chauvin, in 1600, Tadoussac, P.Q., 18 [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.3935.jpg)