Source: Link

CHAUMONOT (Calmonotius, Calvonotti, Chomonot), PIERRE-JOSEPH-MARIE, priest, Jesuit, missionary, called Échon (Héchon) by the Indians; specialist in the Huron language, co- founder of the Confrérie de la Sainte-Famille, founder of the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette mission near Quebec; b. 9 March 1611 at Châtillon-sur-Seine (Côte d’Or, Burgundy); d. 21 Feb. 1693 at Quebec.

In 1688, at Quebec, Father Claude Dablon asked Father Chaumonot to write the story of his life. This autobiography enables us to acquire a thorough knowledge of this missionary, who remains, as Gosselin says, “One of the finest figures in the Church in Canada and one of the purest glories of the Society of Jesus.”

His father was “a poor vine-grower,” and his mother “a poor daughter of a schoolmaster.” After attending his grandfather’s school, Pierre presented himself at the home of his uncle, a parish priest who wanted to make a cleric of him. But a comrade persuaded Pierre to accompany him to Beaune, where the Oratorian fathers taught. He took advantage of his uncle’s absence at church to steal 100 sols from him and to take to flight. This petty theft was to lead him to the Jesuits’ noviciate in Rome and then to the Huron mission in Canada.

Stranded without any funds, and being afraid of “being pointed at as a thief” if he returned home, he decided “to roam about the world as a vagabond.” From Lyons he set off for Italy with another vagabond like himself. After many adventures, which are recounted in a picturesque manner in the autobiography, Pierre Chaumonot, who had been moved by a Jesuit father’s sermon at Terni (Umbria), was presented to the provincial of the Jesuits and accepted by him, and entered St. Andrew’s noviciate in Rome on 18 May 1632. He was 21 years old.

Six months later he was sent with three comrades to the new Jesuit noviciate at Florence where, a year and a half later, he took his vows. He travelled from Florence to Rome, then from Rome to Fermo, near Loreto. There he taught for two years and a half, while relearning his mother tongue which he had forgotten. Back in Rome to study philosophy in preparation for theology, he met Father Poncet de La Rivière, who showed him Brébeuf’s Relation for 1636; on reading it he decided to apply for the missions in Canada. After repeated entreaties he obtained permission to drop his studies, to receive the priesthood as soon as possible, and to go to France (21 Sept. 1637)

Upon his ordination towards the end of 1637 or the beginning of 1638, Joseph-Marie said his first mass in a chapel erected under the name and invocation of the house of the Virgin in Loreto (it was at this time also that he obtained permission to use as his first name Joseph-Marie, because he held Mary in great veneration and because he had learned that Canada was under the protection of St. Joseph). Almost immediately after his ordination Father Chaumonot left Rome with Father Poncet and went to prepare for his mission at the noviciate in Rouen, at the same time doing his third probationary year. Finally the day of departure was set for 4 May 1639, from the quays of Dieppe. The flotilla consisted of three ships, including the flagship Saint-Joseph, which carried Father Barthélemy Vimont, three Ursuline nuns, including Marie de l’Incarnation [see Guyart], four Religious Hospitallers, and Mme de Chauvigny de La Peltrie. Father Claude Jager and Father Chaumonot embarked on the other two ships. Father Poncet also sailed on this voyage. The rough crossing, which has been described at length in the nuns’ letters, did not end until the evening of 31 July; all the travellers, who were brought together on one boat at Tadoussac, landed on the western end of the Île d’Orléans. It was there that next morning the shallop belonging to M. Huault de Montmagny, the governor of New France, picked up the travellers to bring them to Quebec; they were received with open arms, for, according to Father Paul Le Jeune, the colony was receiving “a Jesuit college, a Hospitallers’ house, & a Ursuline convent.” The travellers went directly to the church; they sang the Te Deum, heard mass, and received Holy Communion; they dined at the governor’s house. The people of Quebec took a holiday that day in honour of the new arrivals, who visited the town and its surroundings the very next day. Father Poncet and Father Chaumonot recorded their first baptisms of a few Indians.

On 3 Aug. 1639 Chaumonot was already on his way from Quebec to the Huron country with Father Poncet. Chaumonot himself has told us of this trip, which ended on 10 Sept. 1639 at Lake Isiaragui. Father Chaumonot, was assistant to Father François Du Peron and Father Paul Ragueneau at the former central residence at Ossossanë, which had become the “Mission de la Conception.” It had difficulties at the beginning, especially because of “a sort of smallpox” which scattered the population and for which the witch doctors blamed the fathers, as the French were not affected.

Between this first mission with Father Ragueneau and his departure for the Neutral Nation with Father Brébeuf, 2 Nov. 1640, Chaumonot stayed a short time with the Ahrendarrhonon (Rock) Nation at the Saint-Jean-Baptiste mission (Cahiagué), which at that time was under the direction of Father Antoine Daniel. According to the autobiography and the 1640 Relation, this new position must have been entrusted to him early in the spring of 1640, probably in March, to permit him to learn the Huron language. “Father Daniel,” he said, “gave me this advice. I had to go into a certain number of lodges every day to ask the Indians for the words of their language and to write them down when they were suggested to me.” It was in dirty lodges, amid a thousand mockeries, that the missionaries were to learn the Huron language, “the most difficult of all those of North America,” according to Chaumonot. He was to be rewarded for his work, for he himself declared: “It pleased God so to bless my work, that the Huron possesses no turn of phrase, no subtlety nor manner of expression, that I am not acquainted with and which I have not, as it were, discovered.” After his death someone was to write: “All the Jesuits who will ever learn Huron will do so with the help of the examples, the roots, the speeches, and several fine works which he has left us in this language. The Indians themselves admitted that he spoke it better than they, who for the most part prided themselves on speaking well.” Someone else was to write: “Father Chaumont [sic], who has lived for 50 years among the Hurons, has composed a grammar, which is very useful to those who come for the first time to this mission.”

From that time on his life was to be nothing but a long series of moves in the midst of the greatest difficulties. After his stay with Father Daniel, Chaumonot was sent with Jean de Brébeuf to the Neutrals, with whom they stayed from 2 Nov. 1640 to 19 Mar. 1641. Then he returned with Father Daniel, staying sometimes at Saint-Jean-Baptiste, sometimes at Saint-Joseph II (Teanaostaiaë) or at Saint-Michel (Scanonaenrat). It was at Saint-Joseph II that Father Chaumonot was saved from death by Father Daniel, who very dexterously snatched a hatchet from the hand of an Indian who was about to fell the missionary.

From 1643 to 1645 Chaumonot worked at Saint-Michel with Father Du Peron. We lose sight of him during the years 1645–47, for the Relations make no mention whatsoever of him; it is not until the end of 1647 or the beginning of 1648 that we find him again, at the Saint-Ignace I mission (Taenhatentaron) with Father Ménard. After April 1648 and until 19 March 1649 he carried on his work at La Conception. We know that the Iroquois had sworn to destroy the Hurons. After harrying them for many years, they launched their final offensive in 1649. We also know that from 29 Sept. 1642 to 8 Dec. 1649 the Iroquois martyred eight persons. Having escaped the massacre, Chaumonot did not abandon the Hurons: he sought refuge with them among the Tobacco Nation from 19 March to 1 May 1649, and then on the Île Saint-Joseph (Christian Island) from 1 May to 10 June 1650, when they left for Quebec, which the “small remainder” reached on 28 July, to settle subsequently on the Île d’Orléans (29 March 1651).

On 12 Sept. 1655, in order to lure the Hurons to them, the Onondagas sent ambassadors to Quebec to request that priests be sent them. Following Father Simon Le Moyne’s peace mission in 1654, Chaumonot left Quebec with Father Claude Dablon 19 Sept. 1655 and arrived at Onondaga 5 Nov. 1655. In July 1656 they established the Sainte-Marie-de-Ganentaa mission in Onondaga territory. It was there that Chaumonot delivered several addresses “in the style of the country,” addresses that remained famous among the Indians as well as the French. As there was no end to the Iroquois’ vexations, life rapidly became unbearable and all the French had to flee on 20 March 1658. They arrived back at Quebec on 23 April.

On 19 September Chaumonot was called to Montreal by Governor Voyer* d’Argenson to carry on negotiations with the Onondagas. As he was well acquainted with these Indians and with their habits and language, he was to be sent on embassy by the governor fairly often (13 May 1659, 2 July 1661).

On 2 June 1662 Chaumonot again set off for Montreal, this time “to succour the inhabitants . . . who were suffering from an extreme shortage of supplies.” There, c. 1663, with M. Souart’s permission and the aid of Mme d’Ailleboust [see Boullongne], he founded the Confrérie de la Sainte-Famille, which was to bear much fruit and which still exists. He was to establish the same congregation at Quebec in October 1664. Chaumonot was chaplain of five French companies from 23 July to 3 Oct. 1665. At the same time he continued to look after his Hurons. At the end of that year he was at the post between Quebec and Beauport – at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges – and he stayed there till April 1668. In the spring of 1669 he settled down at Côte-Saint-Michel, still serving the Hurons but sometimes preaching retreats to the nuns in Quebec and performing other ministries.

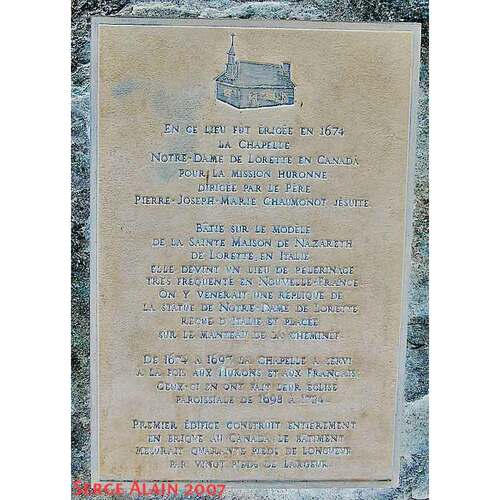

One of Father Chaumonot’s finest claims to fame is that of having founded the celebrated Huron mission of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, three leagues from Quebec. Since the time of his trip to Loreto in Italy he had dreamt of building in New France a chapel modelled on the one in Europe. At that time the missionaries were looking for tracts of land for the Hurons. After much searching and many prayers the Jesuits decided to bestow upon the Indians their seigneury of Saint-Gabriel which was three leagues from Quebec and to which they gave the name of Lorette. When the site for the chapel had been chosen, the plan for the village was drawn up, and in that same summer of 1673 the construction of a few lodges was quickly begun; on 28 December their first inhabitants moved into them. While waiting for the chapel to be built three Hurons generously lent their lodge, in which mass was said for ten months by the fathers, who themselves lived in a hastily erected lodge. On 16 July 1674 Father Claude Dablon, the superior general of the missions of the Society of Jesus in New France and rector of the college in Quebec, laid the first stone. He blessed the chapel 4 Nov. 1674; it had cost 5,000 livres. At the outset nearly 300 Indians (there would be only 146 at the time of the 1685 census) lived at the new mission, which was under the direction of Father Chaumonot. The Relations of the time contain a large number of accounts of the great virtues of the Hurons, who displayed much piety and much charity. The other missions had more inhabitants, but only those who openly professed Christianity and practised the highest virtues were chosen to live at Lorette. Father Chaumonot could see them praying in the chapel and hear them singing hymns in the fields.

Lorette rapidly became a place of pilgrimage for the French. Unfortunately, mingled with the pilgrims, were traffickers in spirits who took up with the Hurons. According to Father Chaumonot, drunkenness was the only vice they had to contend with; in 1687 he wrote that “with spirits moral perversion entered the village.” Father Chaumonot resigned in 1691, after being the first religious to celebrate the golden jubilee of his sacerdotal career at Quebec.

In October 1692 he fell ill; he finally retired to Quebec, to the Jesuit college, and on 21 Feb. 1693 he died, after receiving the rites for the sick on 18 February. He was 82, and had spent 52 years working in New France.

[P.-J.-M. Chaumonot], Un missionnaire des Hurons autobiographie du Père Chaumonot de la Compagnie de Jésus et son complément, éd. Félix Martin (Paris, 1885); Le Père Pierre Chaumonot de la Compagnie de Jésus: autobiographie et pièces inédites, éd. Auguste Carayon (Poitiers, 1869); “Quelques remarques sur les vertus du P. de Brébeuf,” dans ACSM, “Mémoires touchant la mort et les vertus des pères Isaac Jogues . . .” (Ragueneau), repr. APQ Rapport, 1924–25, 68–69; La vie du R. P. Pierre-Joseph-Marie Chaumonot, de la Compagnie de Jésus, missionnaire dans la Nouvelle-France, écrite par lui-même par ordre de son supérieur, l’an 1688, éd. J. G. Shea (2v., New York, 1858). Marie Guyart de l’Incarnation, Écrits (Jamet). JR (Thwaites). Première mission des Jésuites au Canada: lettres et documents inédits, éd. Auguste Carayon (Paris, 1864). Campbell, Pioneer priests. Auguste Gosselin, Vie de Mgr de Laval. Jésuites de la N.-F. (Roustang). Parkman, Jesuits in North America (29th ed); The old régime (25th ed.), 20–39. Rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la N.-F. au XVIIe siècle, I, 399–408, et passim. André Surprenant, “Le Père Pierre-Joseph-Marie Chaumonot, missionnaire de la Huronie,” RHAF, VII (1953–54), 64–87, 241–58, 392–412, 505–23.

Cite This Article

André Surprenant, “CHAUMONOT (Calmonotius, Calvonotti, Chomonot), PIERRE-JOSEPH-MARIE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chaumonot_pierre_joseph_marie_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chaumonot_pierre_joseph_marie_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | André Surprenant |

| Title of Article: | CHAUMONOT (Calmonotius, Calvonotti, Chomonot), PIERRE-JOSEPH-MARIE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |