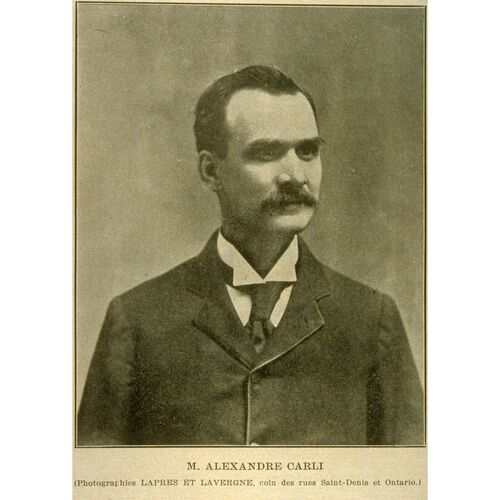

CARLI, ALEXANDRE, sculptor, statuary maker, professor, and businessman; b. 3 Nov. 1861 in Montreal, eldest son of Thomas (Tommaso) Carli and Mathilde Pichette; m. there 12 July 1880 Hedwidge Couture, and they had six daughters; d. there 5 Sept. 1938.

Alexandre Carli belonged to a family of statuary makers who ran an active business in Montreal for over a century. His father, Thomas, was born in Coreglia Antelminelli, near the city of Lucca, Italy, and he immigrated to Lower Canada in 1858 after having worked briefly in Europe and the United States. Other members of the Carli family would join him.

Skilled Italian art workers had been in great demand in Lower Canada since the early 19th century. Stone carvers and cutters, moulders, and plaster-statuary makers were sought after because their specialized skills were required for architectural embellishment. The Roman Catholic clergy in what would become Quebec purchased customized statues of religious figures, nativity scenes, Stations of the Cross, and calvaries (sculptures representing the crucifixion of Jesus) to meet the needs of churches, convents, abbeys, and other institutions. Along with technical expertise, Italian artists brought knowledge of the religious iconography essential to church and cemetery ornamentation. Many remained migrants, moving from city to city and country to country, and were often part of familial and professional networks that included cousins and paesani (fellow villagers).

Thomas Carli soon found employment in Montreal with statuary maker Gaetano Baccerini. In 1864 he prepared three monumental cement statue moulds for Baccerini based on models produced by artist Charles-Olivier Dauphon; they were destined for the facade of Notre-Dame church in Montreal. From about 1867 to 1877 Thomas Carli was in partnership with statuary makers Carlo (Charles) Catelli and Aurelio Giannotti; by 1872 the firm was named C. Catelli and Carli. Five years later he set up his own company, T. Carli.

Thomas had intended his eldest son for a career in commerce, so Alexandre went to business school and worked briefly as an accountant before joining his father’s workshop in 1876. Two years later he entered the school of the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec, which was oriented towards trade occupations and catered to the working class. He studied with François C. Van Luppen and Joseph Chabert* and forged lasting friendships, including one with his moulding teacher, Olindo Gratton*, who would later produce models for him. During the early 1890s Carli exhibited several sculptures that drew praise. In 1898, while continuing in his father’s workshop, he replaced Gratton at the school. He taught there until 1914, when the family business required his complete attention.

The company of T. Carli had prospered. By 1894 it occupied a spacious three-storey building plus two floors of an adjacent warehouse and employed 22 skilled workmen. Most of this work was unsigned. Orders came from across Canada and the United States. By the time of Thomas’s death in 1906 his four sons were all employed in the firm. Alexandre, the sculptor of the enterprise, was also its director. Ferdinand was the accountant, while Edmond and Charles supervised employees and production. Around 1914 cousins Vincent, Apollo, and Urbain, who were statuary makers, closed their firm, Carli et Frères, and by 1915 they had all joined T. Carli; their younger brother Carlo followed them in 1920.

Aimé and Nicholas Petrucci, who, like the Carlis, hailed from the region of Lucca, had opened a statuary workshop in Montreal known as Petrucci Brothers in about 1910. They were successful in obtaining commissions and collaborated with the Carli family on major projects. On 18 May 1923 the two firms fused to become T. Carli-Petrucci Limited, with an authorized capital of $99,000. This capital was probably not entirely paid up. The Bradstreet credit agency estimated in 1925 that the company was worth between $35,000 and $50,000, a significant increase over the evaluation of $10,000 to $20,000 made in 1905, a year before the business’s patriarch died. Alexandre would serve as director until his retirement in 1933 or 1934, and the firm would continue until 1965. The workshop employed, at one time, as many as 60 people. In addition to statues, the business undertook other decorative work, especially for churches, producing stone or marble altars and railings, pedestals, columns, plaster friezes, baptismal fonts, stoups, pulpits, and monuments. In 1925 T. Carli-Petrucci claimed that it executed 90 per cent of this type of work undertaken in Canada. One of its most impressive achievements was the plaster frieze, just over seven feet high and depicting more than 320 figures, that was installed two years later in the church of La Nativité-de-la-Sainte-Vierge d’Hochelaga.

In 1926 Aimé Petrucci and Apollo Carli had left the firm to set up Petrucci et Carli; it would continue to 1972, the last workshop to carry the Carli name. The family tradition, well over a century old, would cease when they went out of business because of decreasing demand – most likely owing to the effects of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution – and rising production costs.

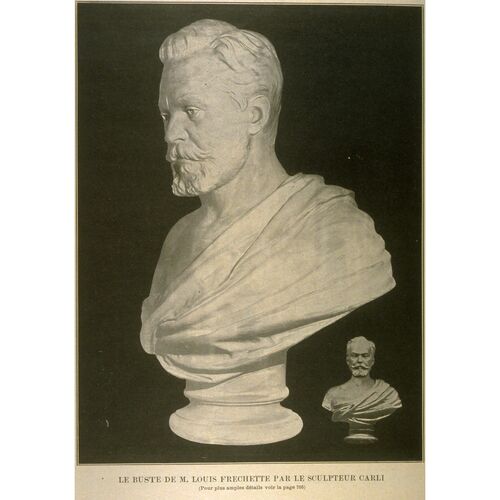

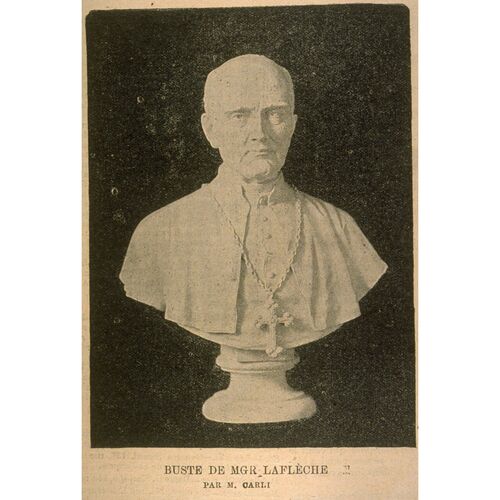

Alexandre Carli took over a prosperous family business and helped it expand through his crucial roles as both a sculptor and its director. He was admired for his ability to work closely with clients, and for his reputation as a teacher. Several prominent artists started their careers as painters for T. Carli or T. Carli-Petrucci, including Ozias Leduc*. Among Carli’s artist friends was Alfred Laliberté*, who had been his student at the council’s school in 1898–99. Laliberté became an important sculptor, whose many commissions often brought him to Carli’s workshop. In the book Les artistes de mon temps, compiled and published posthumously by his niece Odette Legendre in 1986, Laliberté suggests that Carli’s guidance contributed to his winning an important prize that allowed him to travel to Paris for further study. He speculates that unfavourable circumstances, especially the lack of opportunity to study in Europe, hindered Carli’s professional development as a sculptor and prevented him from pursuing a promising artistic career. In a fine-arts show in Montreal in 1890, Carli presented a sculptural grouping comprising a depiction of the Assumption and individual statues of at least seven saints. In a review of the exposition, Le Monde Illustré wrote that all of Carli’s statues were “excellent” and “noteworthy.” With the Art Association of Montreal he exhibited busts of lawyer and writer Laurent-Olivier David* and artist Edmond Dyonnet in 1891 and busts of Bishop Louis-François Lafleche* and Alexandre’s brother Charles Carli in 1892. Yet he did not continue as an independent artist. Laliberté believes that Carli’s artistic career was impeded by his obligations to the family business, which “shackled” him throughout his life. The dominating personality of the family patriarch, Thomas, and the conservative tastes of the firm’s major client, the Roman Catholic Church, may have stifled Alexandre’s creative ambitions. Laliberté also suggests that because Alexander had only daughters and therefore there were no sons to follow in his footsteps, his artistic dreams could never be realized through his children, nor could he fulfil his father’s hope that the family business would continue to the next generation.

Laliberté’s speculations reflect the social conventions of the time. They also reveal the context in which Alexandre Carli evolved and in which many artists of Italian descent found themselves. The chain migration evident in the history of Montreal’s Italian community allowed the Carli business to flourish since there was a continuous flow of skilled and semi-skilled labour, yet Italian family and community ties may have inhibited or at times discouraged individual ambition. Carli, who was secretary of the Italian Mutual Benefit Society of Montreal in 1915, was conscious of the need for Italian immigrants to help one another. Unfortunately, he did not leave behind documentation that expresses his opinion of his own career. Certainly he, his father, brothers, and cousins, and the various firms associated with the family name left a large body of artistic work, the importance of which is still being evaluated.

Works attributed to Alexandre Carli are preserved by the Sisters of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary (Rimouski, Que.), the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec (Québec), and the Soc. du Patrimoine Religieux du Diocèse de Saint-Hyacinthe. Other works attributed to the Carli family can be found at the Musée des Sœurs de l’Assomption de la Sainte Vierge (Nicolet), the Filles de la Charité du Sacré-Cœur de Jésus (Sherbrooke), the Musée des Ursulines de Trois-Rivières, the Marguerite-Bourgeoys Museum and Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel (Montréal), the Notre-Dame Basilica (Montreal), and the Musée des Religions du Monde (Nicolet).

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S15, 12 juill. 1880; CE601-S51, 3 nov. 1861. FD, Notre-Dame (Montréal), 8 sept. 1938. Alain Bernard, “La contribution des ateliers Carli et Petrucci à la statuaire religieuse canadienne (1867–1972)” (unpublished report for the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Can., n.d.). Karel, Dict. des artistes, 146–47. Laurier Lacroix, “Italian art and artists in nineteenth-century Quebec: a few preliminary observations,” trans. David Homel, in Arrangiarsi: the Italian immigration experience in Canada, ed. Roberto Perin and Franc Sturino (Montreal, 1989), 163–78. Alfred Laliberté, Les artistes de mon temps, Odette Legendre, édit. (Montréal, 1986), 74–76. Claude Lamarche et Jacques Lamarche, Dictionnaire biographique Guérin: Québec-Canada/2000 (Montréal, 1999), 78. Luc Noppen, “Le rejet du plâtre dans l’étude de l’art ancien du Québec: un point de vue,” Rev. d’ethnologie du Québec (Trois-Rivières), no.1 (1975): 25–48. J. R. Porter et Léopold Désy, L’Annonciation dans la sculpture au Québec suivi d’une étude sur les statuaires et modeleurs Carli et Petrucci (Québec, 1979), 127–37. Bruno Ramirez, Les premiers Italiens de Montréal: l’origine de la Petite Italie du Québec (Montréal, 1984). Luce Vignola, “Essai de définition: les sculpteurs, statuaires et ornemanistes italiens à Montréal de 1862 à 1880” (mémoire de ma, Univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1996).

Cite This Article

Anna Maria Carlevaris, “CARLI, ALEXANDRE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carli_alexandre_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carli_alexandre_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Anna Maria Carlevaris |

| Title of Article: | CARLI, ALEXANDRE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |

![M. Alexandre Carli [image fixe] / A.J. Rice, Laprés & Lavergne Original title: M. Alexandre Carli [image fixe] / A.J. Rice, Laprés & Lavergne](/bioimages/w600.7555.jpg)