Source: Link

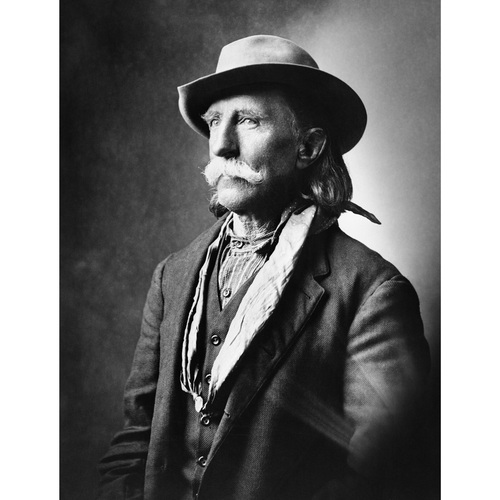

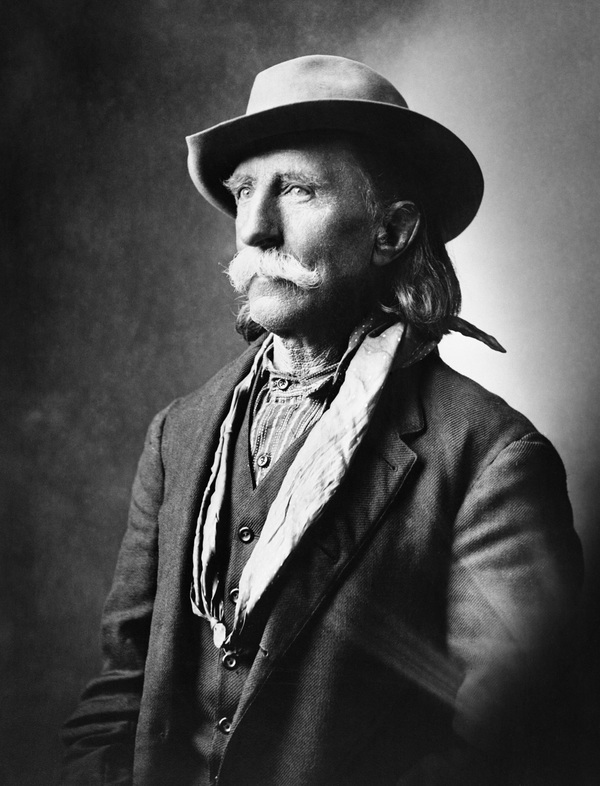

BROWN, JOHN GEORGE, known as Kootenai Brown, prospector, frontiersman, and park superintendent; b. 10 Oct. 1839 in Ennistymon (Republic of Ireland), son of John George Brown and Ellen Finucane; m. first 26 Sept. 1868 Olive Lyonnais in Pembina (N.Dak.), and they had two daughters and one son; m. secondly Cheepaythaquakasoon (Isabella); they had no children; d. 18 July 1916 in Waterton Lakes National Park, Alta.

Orphaned when very young, John George Brown was brought up by his grandmother. His grandfather had been an officer in the British army, and through persistent letters to the War Office, his grandmother obtained a commission without purchase for Brown on 13 Dec. 1857. An ensign in the 8th Foot, he served briefly in India. In 1861 he left the army, sold his commission, and with his friend Arthur Wellesley Vowell set out for the Cariboo gold-field in the new colony of British Columbia.

After arriving in Victoria in February 1862, the two proceeded to the diggings but failed to make a strike. Vowell returned to the coast; Brown remained until news of gold at Wild Horse Creek (Wild Horse River) tempted him to move on. Again fortune eluded him. Instead, in March 1865 he obtained employment as a constable. In July, however, he and four companions set out through the mountains for Fort Edmonton (Edmonton), once more in pursuit of gold.

Having made their way through the Boundary (South Kootenay) Pass, they came upon the Kootenay (Waterton) Lakes, in what is now southwestern Alberta, and Brown later said he resolved then and there to come back to that beautiful country some day to live. Soon after, an encounter with a Blackfoot war party during which he was wounded, together with differences between the travellers, split the group. Brown made his way to Duck Lake (Sask.), where he wintered with the Métis before continuing to Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) in the spring of 1866.

Brown traded with the Indians in the Whitemud River area until the next year, when he found employment as a mail carrier with a private company operating a pony express service for the United States Army in the Dakota and Montana territories. That enterprise failed in 1868, but the army hired Brown as a civilian “tripper.” For the next six years he served as a carrier, contractor, guide, and interpreter, surviving accidents, unpredictable weather, and uncharted terrain. He almost lost his life in May 1868 when he was captured by Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*] and his warriors, who were resisting the presence of the army on their lands.

When Brown left the army’s employment on 4 June 1874, he and his family joined the Métis community to which his wife belonged. With her people he took part in some of the last great buffalo hunts, and after the buffalo herds disappeared from the area he briefly turned to poisoning wolves for their pelts. In April 1877 he killed a man in a quarrel. Jailed at Fort Benton, Mont., he attempted suicide. A territorial grand jury found insufficient evidence to charge him with murder, however, and he was released on 12 November.

True to his earlier resolve, Brown then took Olive and their children to the Kootenay Lakes. After a brief trading partnership, he settled into sustaining them by the area’s abundant fish and wildlife. Periodically he took temporary jobs as a packer and guide for the North-West Mounted Police. Sometime between the autumn of 1883 and the spring of 1885 Olive died. Their son was placed in the Roman Catholic mission school at St Albert; what became of their daughters is not clear. Within a few years Cheepaythaquakasoon, a Cree woman, came to live with Brown as his country wife. She spoke no English, although she understood it, but she was an excellent shot and often travelled with him, keeping camp while he hunted for big game.

When the North-West rebellion erupted in 1885 Brown served as chief scout with the Rocky Mountain Rangers, an ad hoc defence force raised by residents in the area of Fort Macleod. Although the unit carried out patrols, it never saw action. Similarly, because of his familiarity with the region, in 1888 he accompanied the NWMP contingent returning from Wild Horse Creek, where it had been sent to prevent unrest among the Kutenai Indians from escalating into hostilities [see Isadore*]. In 1898 he was employed as a packer with private companies servicing the Canadian Pacific Railway when it thrust its way through the Crowsnest Pass.

As the CPR made western Canada more accessible to outsiders, Brown began to guide parties in the Kootenay Lakes area. The growing number of visitors, however, alarmed him and neighbouring ranchers, and they voiced their concerns to federal officials and politicians about the impact on the region’s flora and fauna. On 30 May 1895 Ottawa set aside a township and a half as the Kootenay Lakes Forest Reserve. Brown was appointed the fishery officer in 1901 to establish a government presence, and he held the post until 1912. In his reports he persistently stressed the need for greater conservation measures, particularly as the effects of a brief oil boom [see John Lineham] manifested themselves. By then nicknamed Kootenai Brown because of his long residence in the region and his known commitment to the reserve, he was given additional powers as forest ranger in 1910, when more supervision was deemed necessary. Four years later, largely on his recommendation, the reserve was greatly expanded and accorded the status of a national park. Renamed Waterton Lakes National Park, it was put under the superintendence of someone else. Brown, who was 75, was kept on as a park ranger until his death.

An accomplished raconteur, in his later years Kootenai Brown delighted in telling tales of the old west to newcomers. He was interested none the less in the changing world around him. In his seventies he requested a typewriter to help him with his correspondence as forest ranger. “Practicing on typewriter,” he notes more than once in his diary. He subscribed to various magazines and newspapers and owned a surprisingly large library. During stormy weather he was frequently “at home all day reading.” As he grew older, Brown became increasingly concerned about spiritual questions. Perhaps because he had encountered a wide variety of religions over the years, he was drawn to theosophy rather than one of the conventional churches. In 1898 he applied to join the Theosophical Society in America, and he remained a staunch supporter of it for the rest of his life.

Since 1916 numerous newspaper reports and articles in periodicals have perpetuated the myths and legends that came to be associated with Brown. Most are epitomized in [J. W.] G. MacEwan, Fifty mighty men (special ed., Saskatoon, 1982). Various inaccuracies are also repeated in George Woodcock*, Faces from history: Canadian profiles & portraits (Edmonton, 1978). A full listing of sources for Brown’s life can be found in William Rodney, Kootenai Brown: his life and times, 1839–1916 (Sidney, B.C., 1969).

Cite This Article

William Rodney, “BROWN, JOHN GEORGE, known as Kootenai Brown,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_john_george_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_john_george_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | William Rodney |

| Title of Article: | BROWN, JOHN GEORGE, known as Kootenai Brown |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |