Source: Link

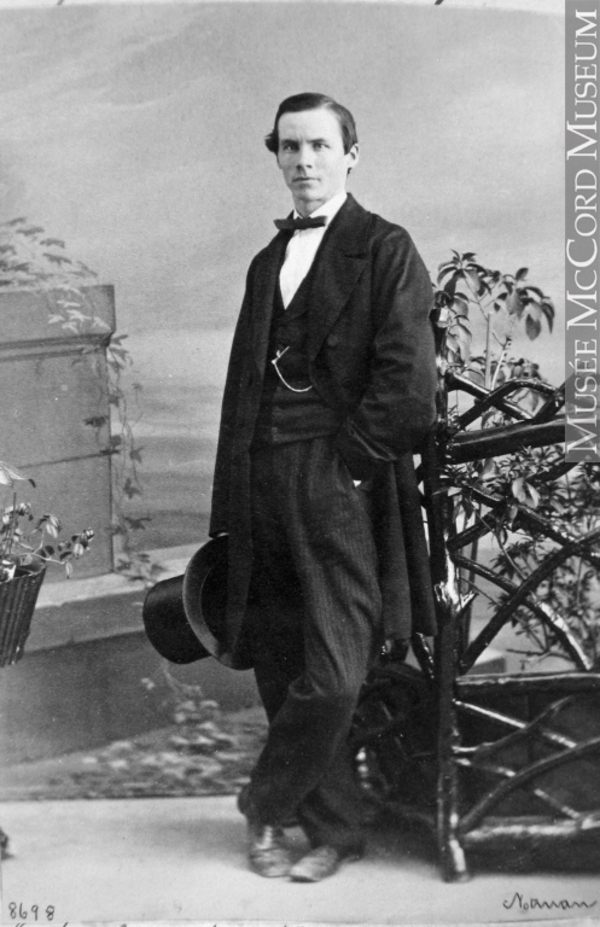

BRODIE, ROBERT, businessman; b. 11 May 1835 in Montreal, son of Charles Brodie and Elizabeth Kerr; m. 31 Oct. 1865 at Quebec Jane Blair, daughter of David Blair of Lotbinière, Lower Canada, and they had three daughters and two sons; d. there 30 May 1905.

Robert Brodie’s parents, who were born in Scotland, immigrated to Lower Canada in 1831. Brodie went to school in Montreal and then at the age of 15 entered the employ of Henry Morgan and Company, which specialized in dry goods. In 1855 he left the company and moved to Quebec, where his brother Charles owned a flour and grocery business on Rue Saint-Paul. Opened in 1850, the store was small and in 1858 had a stock in trade valued at between £500 and £750. After the death of Charles in 1859, Robert and his brother William formed a new partnership, W. and R. Brodie. Their financial base enabled them to obtain a good credit rating and make a profit. They were considered good administrators but rather tight-fisted.

In 1868 their brother Thomas joined the firm as a partner. W. and R. Brodie came through the 1860s and the following decade without difficulty, growing steadily, with no sudden ups or downs. At the outset of 1880 its capital was valued at between $50,000 and $75,000, and in 1881 at between $75,000 and $100,000. The enterprise had no difficulty in maintaining its capital at the latter level throughout the decade. Henceforth it monopolized flour distribution at Quebec, in the lower St Lawrence region, and in the Gaspé peninsula. Its major competitor during the 1870s, J.-B. Renaud et Compagnie, suffered a serious loss of capital with the death in 1884 of its principal shareholder, Jean-Baptiste Renaud*. The Brodie enterprise benefited from this occurrence as well as from the effects of the National Policy [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*].

The three Brodie brothers aspired to become part of the business élite of Quebec. One of their first spheres of influence was the Stadacona Bank, founded in 1873, whose liquidation they vigorously opposed in 1879. Along with Evan John Price* and Charles Pentland, they formed a minority group challenging the decision. According to a circular signed by Robert Chambers, mayor of Quebec and chairman of the shareholders’ meeting, the bank’s balance sheet was in the black. In the last fiscal year, it had a paid-up capital of more than $990,890 and had also managed to make good investments, in spite of the pronounced business recession. To proceed with liquidation on the grounds that the returns and profit margin no longer enabled the bank to be competitive would thus be ill advised, it was argued. 1n the view of the opposition group, the normal voting procedure on this crucial question had been bypassed. Of the 4,231 votes cast in favour of liquidation, more than 2,000 had been proxies. This process seriously compromised the confidentiality of the vote by ballot and was contrary to the methods laid out in the bank’s charter. It was a highly unorthodox use of the rules and had distorted the results of the voting, in which 3,699 ballots had been cast in favour of the bank’s continued existence. The Brodies’ disapproval did not carry sufficient weight to change the outcome, however, and the Stadacona Bank shut down.

The defeat had little effect on the position Robert Brodie held within the Quebec business élite; like that of his brothers, it seems always to have been marginal. Brodie was one of the first to try to diversify the city’s economy following the onset of depression in 1873. In 1883 he helped organize and bought shares in the Riverside Worsted Company, a woollen mill that had begun in 1881 as the Canada Worsted Company. By 1885 the factory had a paid-up capital of $200,000, but its profit margin did not attract new money. In 1886 it was reorganized as the Quebec Worsted Company, with capital limited to $60,000. Within two years, $50,000 had been paid up. However, the board of directors and its chairman, Pierre Garneau, did not succeed in making the enterprise profitable and it was finally sold in 1890 to a group headed by Andrew Paton* of Sherbrooke. Brodie was the only Quebec resident to keep a seat on the board. He still had some decision-making powers but his position was tenuous. In 1891 a boiler explosion destroyed much of the factory and, for the moment, ended his hopes of bringing variety to the city’s economic life by means of a textile industry. At a special shareholders’ meeting, Brodie was assigned the task of liquidating the company.

Brodie still continued to invest in the textile sector, but on a much smaller scale. Now a minority shareholder in the Paton Manufacturing Company of Sherbrooke, he was no longer given any administrative duties. However, in 1894 the Montmorency Cotton Manufacturing Company, a firm founded in 1889 and affiliated with Dominion Cotton Mills of Montreal, underwent administrative reorganization. As a result, Brodie and other Quebec investors were able to regain a foothold in the textile sector. The Riverside Manufacturing Company was set up as a subsidiary and Robert and William Brodie became shareholders in it. Like the Montmorency Cotton Manufacturing Company, its destinies were presided over by Montreal businessman Charles Ross Whitehead*, and the two firms merged in 1898, becoming the Montmorency Cotton Mills Company. Its capital of $200,000 was largely subscribed and paid up by business circles in the city of Quebec. Despite increased demand for textiles on the Chinese and African markets, in the years after 1900 the Quebec investors would lose control of the company, which fell into the hands of a Montreal group headed by Louis-Joseph* and Rodolphe* Forget. In 1905 the mill would become part of the Dominion Textile Company.

During the 1890s W. and R. Brodie consolidated its business position. As of 1893 its capital assets were valued at between $100,000 and $150,000. When Thomas died in 1894, however, the company was liquidated. Robert and William took the opportunity to retire.

The two brothers then embarked on a second career, centring on the administration of their portfolio of stocks. In general they invested in the fields of finance, transportation, textiles, iron and steel, and mining. Robert put his money largely into banks, while William concentrated more on industry and mining. At his death Robert held shares worth $39,200 in four banks and a trust company; 70 per cent of it was in the Canadian Bank of Commerce. In the industrial sector he had assets of $15,300, half as much as William owned in stocks and shares. The main investments of the Brodies were in the Dominion Textile Company and the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company Limited. Mining speculation was more particularly William’s purview, although Robert did put $3,200 into prospecting and mining companies in Nova Scotia and British Columbia. William, for his part, invested in mining in Nova Scotia and the state of Washington, but as it turned out, for no return. Both of them were also attracted to transportation companies and some $10,000 was sunk in such ventures, mainly in the Quebec Steamship Company Limited and, to a lesser extent, the Quebec and Levis Ferry Company Limited and the Micmac Steamship Company Limited in Nova Scotia. They also invested in the Aetna Life Insurance Company, based in Connecticut, the London and Lancashire Life Assurance Company, the Royal Insurance Company of Liverpool, and the Scottish Provincial Assurance Company of Aberdeen. Each brother held life insurance policies with a value of between $10,000 and $14,000. The only important difference between their assets was in real estate: Robert owned a residence on the Grande Allée, while William, at his death in 1908, owned nothing but a plot in Mount Hermon Cemetery, where his brothers were buried.

Throughout their lives, the Brodies had shown strong solidarity as a family. They had embarked together on their business and social careers. They had given their energies to the development and growth of their firm and thus had been able to associate with the élite and its networks of power. However, they had never gained wide acceptance of their views and had remained marginal. Perhaps Robert believed more strongly than William in climbing the social ladder, but he had been no more successful than his brother in that endeavour. Nevertheless, Robert was true to the image he projected. A staunch Presbyterian and teetotaller, he had banned alcohol from his life, even advocating that it be abolished by law. Although he was a shrewd administrator, he had been, like William, somewhat off the mark in believing that the economy of Quebec City could be diversified.

AC, Québec, État civil, Presbyterians, Chalmers Free Church (Quebec), 1 June 1905; Minutiers, E. G. Meredith, 21 août 1903, 28 nov. 1905, 30 juill. 1908. ANQ-M, CE1-121, 8 sept. 1836. ANQ-Q, CE1-67, 31 oct. 1865; CN1-294, 31 juill. 1879; T11-1/28, no.613 (1859); 30, nos.4704 (1891), 5640–41 (1895). Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 8: 131. Le Canadien, 29 juill. 1879. L’Électeur, 13–14, 19, 21 févr. 1891. Quebec Chronicle, 31 May 1905. Quebec Morning Chronicle, “Special trade ed.,” May 1894. Le Soleil, 19 oct. 1900, 31 mai 1905. Benoit, “Le développement des mécanismes de crédit et la croissance économique dune communauté d’affaires,” 283–84, 306, 390–91, 394. Bradstreet commercial report, 1862–64, 1867, 1871–73, 1875, 1878–81, 1883, 1885, 1887–89, 1891, 1893. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), 2: 374–75. Poulin, “Déclin portuaire et industrialisation,” 83.

Cite This Article

Jean Benoit, “BRODIE, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brodie_robert_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brodie_robert_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Benoit |

| Title of Article: | BRODIE, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |