Source: Link

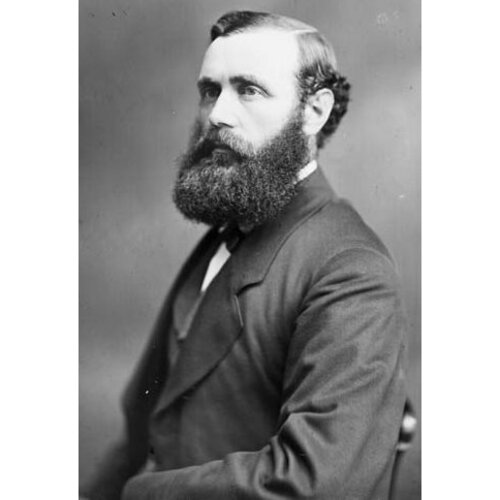

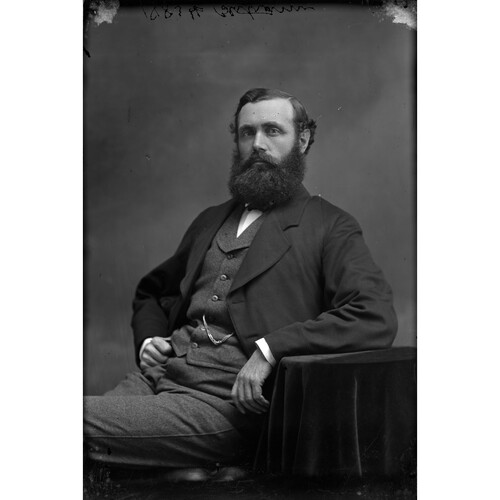

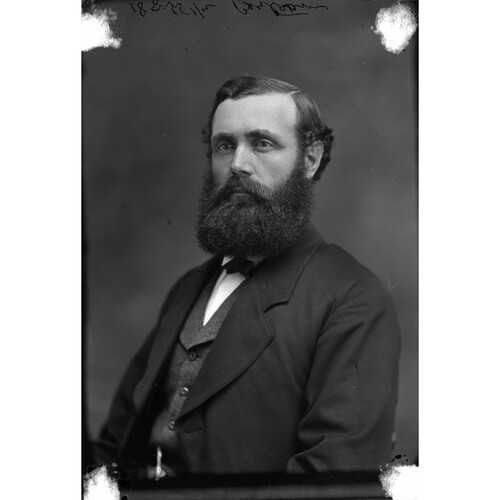

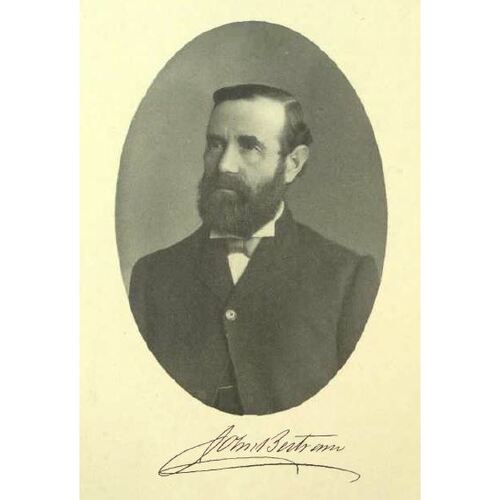

BERTRAM, JOHN, businessman and politician; b. 16 Oct. 1837 in Fenton Barns, Scotland, son of Hugh Bertram; m. 16 Sept. 1863 in Almonte, Upper Canada, Helen Shiells of Edinburgh, and they had four sons and three daughters; d. 28 Nov. 1904 in Toronto and was buried in Peterborough, Ont.

One of six children, John Bertram was educated in the parish school at Dirleton, near Fenton Barns. He was later apprenticed to a merchant in Galashiels, where he learned the rudiments of business management. Having cast for his fortune first in Edinburgh, he decided in 1860 to emigrate to British North America. He settled in the Peterborough area and was joined in 1865 by his brother George Hope*, who located in Lindsay. In 1867 John obtained enough capital to launch a wholesale hardware business in Peterborough; it was soon expanded to include a store in Lindsay, under George’s management. The business was attuned to the farming and lumber economy of the area as settlement moved up the Trent and Otonabee watersheds into the Haliburton highlands. This exposure to the resource frontier of central Ontario deeply influenced Bertram’s later career.

Bertram had ambitions to rise in Peterborough’s business community. He managed to take the Reform nomination in Peterborough West for the federal election of 1872 and he won the seat, even though Tory timber interests normally controlled the area. However, he was disqualified for not having established his eligibility as a candidate. Re-elected in the general election two years later, he was defeated by timber merchant George Hilliard in the Liberal–Conservative resurgence of 1878.

In 1874 Bertram had sold his interest in the hardware business to his brother and begun to seek investments in northern Ontario, which, it was rapidly being recognized, was providing the key to the province’s economic growth. He invested in timber limits on the north shore of Georgian Bay and in 1885 established the Collins Inlet Lumber Company to exploit the rich pineries of that region. The company expanded its holdings into Manitoulin Island, Algoma, and the Parry Sound district, and developed as the centre-piece of Bertram’s business empire. As the Ottawa valley became lumbered out, the attention of Canadian operators shifted to Georgian Bay. At the same time, American lumbermen, who had exhausted the forests of Michigan, cast their eyes north for new sources of supply. High-risk investments made in the difficult times of the late 1870s and early 1880s quickly became extremely profitable.

Though Bertram had turned his back on political life in 1878, he did not lose his interest in public issues, especially as they related to natural resources and national development. His years in Peterborough had exposed him to the worst effects of fire, over-cutting, and agricultural settlement on marginal land. He had seen areas turned into wasteland and, for this reason, he tried to foster more careful harvesting and forest protection on his timber limits in northern Ontario. Indeed, he became a leading advocate of protection and the classification of land for either timbering or settlement.

At the same time, Bertram had a sense of place as a businessman. In the early 1880s he joined once more in the hardware business with his brother George, who had moved to Toronto in 1881. John relocated there himself in 1887 and within a few years the brothers had also set up an engine and shipbuilding works. Positioned in a metropolis that controlled a huge, resource-rich hinterland, Bertram was only one of many entrepreneurs who wished to ensure that the resources were manufactured in Canada before being shipped to international markets, and who thus began to reassess the prevailing association of the Liberal party with free trade. George would persuade Wilfrid Laurier*, prime minister from 1896, to modify Liberal policy toward a protective federal tariff. John Bertram was as committed as his brother to Canadian manufacture, transportation, and trade of natural resources as the basis for national development.

These themes dominated the last decade of Bertram’s life. In June 1897, because of his business credentials as a lumberman and his party ties to the provincial Liberal government, he was appointed, with Edward Wilkes Rathbun, Alexander Kirkwood, J. B. McWilliams, superintendent of forest rangers, Peterborough, and Thomas Southworth, clerk of forestry for Ontario, to a provincial royal commission on forest protection. Its role was to investigate the restoration and preservation of timber on nonagricultural lands. Tabled in 1899, the commission’s report recommended better fire-protection measures, thorough provincial regulation of cutting practices, classification of provincial lands (including the establishment of forest reserves), and a greater limit on tree size for governing the harvesting of white pine. The report marked a turning point in Ontario timber policy: for the first time serious consideration was given to preserving a productive timber base rather than simply regulating the clearing of land for settlement.

Later in 1897 Bertram had found himself embroiled in a controversy over trade in forest products with the United States. The American Dingley tariff of 1897 placed a duty on finished lumber imported into the United States, and thus ended a short period of free trade in wood products between the two countries. The duty had been advocated by mid-western American lumbermen to prevent Canadian exports from entering a depressed market and, at the same time, to open up the timber along Georgian Bay to their companies, by allowing unmanufactured logs to be towed duty-free to mills in Michigan. To ensure these results the tariff contained a clause that doubled existing duties if Canada retaliated by raising its tariffs.

Bertram became a leader among businessmen involved in pushing back this American resource grab. Lumbermen in Ontario had traditionally favoured free trade. Many operators, particularly those in the Ottawa valley, such as John Rudolphus Booth* and William Cameron Edwards, remained convinced of its validity and were prepared to await a negotiated settlement. Bertram, however, was among those who saw merit in guaranteeing Canadian manufacture of raw materials. His position on the tariff was also influenced by the fact that northwestern Ontario lumbermen, burdened with debt charges, were not well able to wait out the political and economic storm. Furthermore, they believed that they had a right to the timber which could be towed to Michigan. Bertram therefore advocated an aggressive solution to the tariff crisis, and in this endeavour he was joined by E. W. Rathbun and Georgian Bay lumberman John Waldie.

The Laurier government expressed its sympathy but the retaliatory clause prevented it from making any quick, effective response. Bertram rapidly became convinced that the northwestern lumbermen would have to take the matter into their own hands. He and Waldie had been active in revamping the Ontario Lumbermen’s Association, which had existed from the late 1880s but had become moribund. They now turned it into a powerful lobbying device to put pressure on the provincial government and to rally sentiment against American actions.

It is not clear who conceived the idea of imposing a provincial “manufacturing condition” in timber licences, which would require that logs cut on crown lands be made into lumber in Ontario. Both Bertram and Rathbun had argued publicly that national and provincial economic policies should prevent logs from being exported in an unmanufactured state; they even claimed such a ban as a conservation measure. Whoever was responsible, the idea developed in the public mind as a resolution to the problems posed by the Dingley tariff.

The Ottawa valley lumbermen remained concerned that such action would bring American retaliation and impossible trade conditions. Bertram worked hard to get them to participate in the lumbermen’s association and take its side. He was partially successful, for they adopted a position of suspicious neutrality, as opposed to outright hostility. Proceeding from this compromise, however, Premier Arthur Sturgis Hardy moved to restrict, by means of the “manufacturing condition,” the export of logs cut on crown lands. He had the control take the form of an amendment to the Crown Timber Act, making it a decision of the legislature as a whole. Given royal assent in November 1897, the amendment took effect at the end of April 1898. The ban, which was subsequently supported by the courts in the face of a challenge by American interests, was not only a triumph for Bertram’s own business but also a demonstration of his statesmanship. The “manufacturing clause” was to be a major plank in Ontario’s economic policy for years to come and the concept would be used in determining provincial approaches to other natural resources.

Bertram’s subsequent business interests and advocacy focused strongly on transportation. With the death of his brother George in 1900, he assumed the presidency of the Bertram Engine Works Company Limited, which serviced the growing transportation industry on the upper Great Lakes. Active in various business organizations, he expressed worries about Canadian railway monopolies and discriminatory transportation rates. As well, he advocated both protection for Canadian steel-ship construction against British competition and the enforcement of coastal-shipping regulations to reduce American competition. He also supported provincial control over railways built into northern Ontario to avoid the alienation of rich land grants to speculators.

Bertram’s interest in transportation led Laurier in 1903 to appoint him a member of the federal royal commission on transportation, formed to investigate growing problems with getting Canadian goods to world markets and with competition from American railways and vessels, and to make recommendations on developing Canada’s water-way systems. When Sir William Cornelius Van Horne* declined to serve as its chairman, Bertram was named to the post. He indicated that the commissioners’ first challenge was to find the “shortest and cheapest route from Lake Superior to the markets of England” and then to tackle the problem of a port on Hudson Bay. He was proceeding with the work of the commission when he fell ill in June 1904. He never recovered, dying at his home on Walmer Road on 28 November. While in Peterborough Bertram had abandoned Presbyterianism in favour of Unitarianism, though his wife had not. At his funeral a minister of each faith officiated.

John Bertram was a successful entrepreneur who eagerly embraced new ideas in both business and public service. These thrust him to the forefront of Ontario businessmen who were advocating progressive, nationalist policies to underpin resource development in Canada during the late 19th century.

An unpublished article by John Bertram on the lumber and timber industry is found in the Collins Inlet Lumber Company records at AO, F 265, MU 7252.

AO, F 248, minute-book; RG 22, ser.305, no.17447. NA, MG 26, G: 11046. Globe, 29 Nov. 1904. Michael Bliss, A living profit: studies in the social history of Canadian business, 1883–1911 (Toronto, 1974). R. C. Brown, Canada’s National Policy, 1883–1900: a study in Canadian-American relations (Princeton, N.J., 1964). Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1903–4. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Commemorative biog. record, county York. CPG, 1876–78. R. P. Gillis and T. R. Roach, Lost initiatives: Canada’s forest industries, forest policy and forest conservation (Westport, Conn., 1986). Index to incorporated bodies and to private and local law under dominion, and Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec statutes, proclamations and letters patent . . . , comp. P.[-H.] Baudouin (Montreal, [1897]), 112. R. S. Lambert with [A.] P. Pross, Renewing nature’s wealth: a centennial history of the public management of lands, forests & wildlife in Ontario, 1763–1967 ([Toronto], 1967). Nelles, Politics of development. Ont., Royal commission on forestry protection and perpetuation in Ontario, Preliminary report (Toronto, 1898). Ont. Gazette, 1885: 121–22, 128, 411. [E. W. Rathbun], Shall we place an export duty on saw logs and pulpwood? ([Deseronto, Ont., 1897]).

Cite This Article

Robert Peter Gillis, “BERTRAM, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bertram_john_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bertram_john_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Peter Gillis |

| Title of Article: | BERTRAM, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |