Source: Link

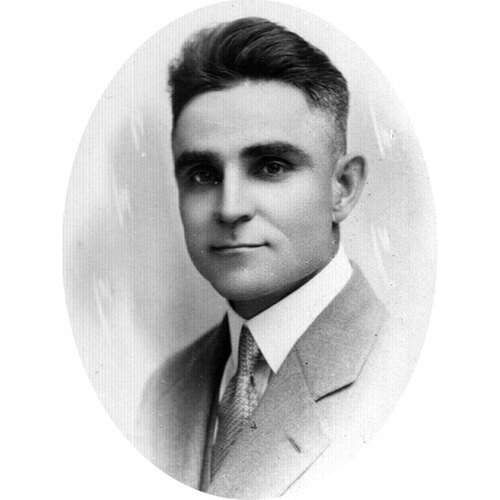

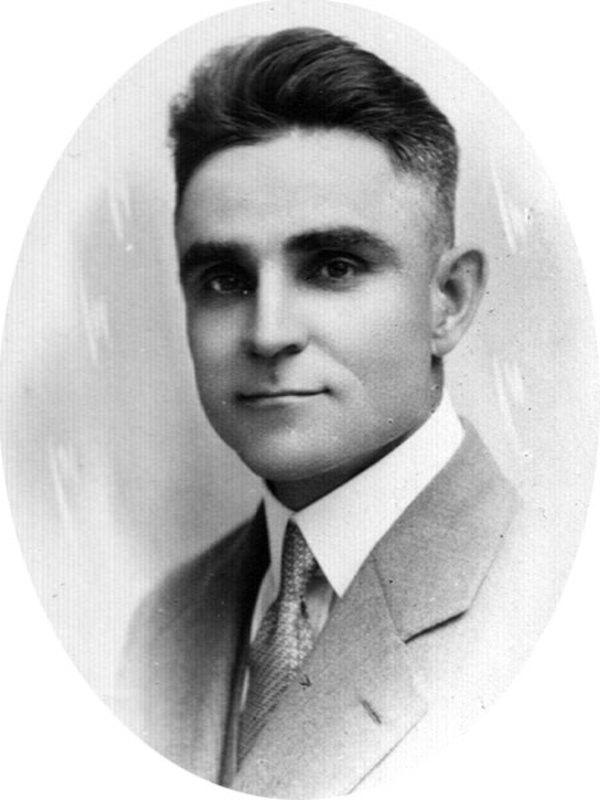

BARAGAR, CHARLES ARTHUR, physician, army officer, psychiatrist, psychiatric-hospital superintendent, and university professor; b. 22 Feb. 1885 in Rawdon Township, Ont., second eldest of the six children of Charles Inkerman Baragar and Emily Sophia Bell; m. 12 Sept. 1918 Marie Blanche Eugenie Ledoux (1886–1930) in Orpington (London), England, and they had two sons and one daughter; d. 8 March 1936 in Edmonton.

Charles Arthur Baragar’s father moved his family from Ontario to Manitoba in 1892 and became a community leader in Elm Creek, a small settlement southeast of Portage la Prairie. The Baragars were Methodists, and Charles Arthur, the eldest son, attended Wesley College at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, receiving a ba in 1910 and an md and cm (master of surgery) four years later. While pursuing his studies, he became an assistant to Dr David Alexander Stewart at the Manitoba Sanatorium, a centre for the treatment of tuberculosis that was near Ninette. Baragar was made assistant medical superintendent of the facility in 1914.

The First World War began that August, and on 22 Feb. 1915, his 30th birthday, Baragar volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Force and was accepted despite having a heart lesion caused by a childhood bout of rheumatic fever. He was assigned to the Canadian Army Medical Corps at the rank of lieutenant and went overseas with the 27th Infantry Battalion. He suffered from acute rheumatism during the war, but nevertheless served with the No.3 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station and the No.1 Canadian General Hospital in France as well as at various hospitals in England. He was brought to the notice of Great Britain’s secretary of state for war on 24 Feb. 1917 “for valuable service rendered in connection with the war.” On 12 Sept. 1918, while stationed at the Canadian Special Hospital in Lenham, he married nurse Eugenie Ledoux, a native of Quebec who had been raised in Manitoba and had worked with him at the Manitoba Sanatorium. Baragar was demobilized at the rank of major on 8 Sept. 1919, nearly a year after the armistice.

The experience of treating soldiers, particularly those with mental illnesses such as shell shock, deeply affected Baragar. He became interested in the developing field of psychiatry, which he studied in 1919–20 at the Bloomingdale Asylum in White Plains, N.Y., the Manhattan State Hospital and the Vanderbilt Clinic in New York City, and the Psychopathic Hospital in Boston. He was a supporter of the mental-hygiene movement headed by American activist Clifford Whittingham Beers, who in 1909 had founded the National Committee for Mental Hygiene. In 1918 Toronto physician Clarence Meredith Hincks* and University of Toronto professor Charles Kirk Clarke*, along with Dr Helen MacMurchy* and others, organized the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene. Hincks and Clarke became nationally acknowledged psychiatric consultants for the assessment of medical facilities. After they had examined mental-health institutions in Manitoba and called for sweeping changes to be made, the new provincial psychiatrist, Alvin Trotter Mathers, appointed Baragar medical superintendent of the Brandon Insane Asylum (which, in an indication of changing public attitudes towards mental illness, was renamed the Brandon Hospital for Mental Diseases [BHMD] in March 1919).

Baragar took up his position in 1920 and would preside over a decade of physical expansion and new treatments at the BHMD. Rejecting electrotherapy and limiting the use of restraints, he preferred hydrotherapy as a means of calming agitated patients. He used drug therapies and promoted the establishment of a provincial social-service department to investigate home conditions. Unlike his fellow superintendent Dr Robert Menzies Mitchell, who mostly concerned himself with administrative matters at the mental hospital in Weyburn, Sask., Baragar took a keen interest in patients. He implemented weekly staff meetings to assess new admissions, developed customized treatment strategies, and kept detailed patient records.

Baragar constructed the Farm Colony Building, separate from the main facility, to house chronic patients. Opened in January 1921, it included three wings with dormitories, a day room, a sunroom, lavatories, and a kitchen and dining room, as well as attic rooms for staff. Baragar reported that even dementia patients demonstrated an improved “mental attitude” after they were moved into their new quarters. In 1925 the Psychopathic Hospital (also called the Receiving Hospital), which had taken five years to build owing to scarce provincial funding, finally opened. Baragar noted in that year’s report: “Here each acute and recoverable case may be fully investigated and may receive more personal care from medical and nursing staff, together with such special forms of treatment as Hydrotherapy and Occupational Therapy. Here the patient is also protected to a large extent from the chronic, demented patient, thus preventing in a measure the feeling of disgrace that has so often remained in the mind of the recovered patient and which stands in the way of full readjustment.”

The BHMD’s department for occupational therapy was opened on 1 June 1921. As Baragar saw it, the purpose of occupational therapy was “to enable the patient to recover his normal mentality more rapidly and more completely, or if he is not recoverable, to arrest to some extent the processes of mental deterioration that tend to take place in the chronically insane.” Equipment was provided for working with wood and metal, printing, bookbinding, sewing, weaving, and creating art. Baragar envisioned that sales of goods would pay for future supplies. These initiatives were praised in the local media. A shortage of teachers meant that some patients continued in older forms of employment, now termed industrial therapy. In 1925, according to Baragar’s estimates, about 106 patients were involved daily in work such as shovelling coal and handling farm animals; roughly 195,000 hours were put in that year for a value to the hospital of over $27,000. A range of recreational activities was also provided.

Recruiting and keeping physicians was an issue for Baragar – at times in 1921 there was only one doctor available to treat the BHMD’s approximately 800 patients – and acquiring professional staff became a priority. As soon as he was able, Baragar hired two doctors and, in 1923, he arranged for medical students from the University of Manitoba to work at the BHMD for four months in the summer to learn about the treatment of mental illness. He established a residence for nurses, thereby freeing up more beds for patients, and implemented a training program with a mental-health specialization for nurses, the first of its kind in western Canada and one of his greatest achievements. Baragar wrote, “The nursing of mental patients requires women of finer personality, of wider sympathies, greater self-control and higher intelligence than even the nursing of those who are physically ill.” One graduate, Mary MacKenzie, went on to obtain her medical degree at the University of Manitoba and would join the BHMD in 1929 as a doctor in the Psychopathic Hospital. Early on, Baragar had also created two-year training programs for supervisors and attendants. While these initiatives were successful – 39 female nurses and 11 male attendants had received diplomas by the end of 1926 – Baragar’s program for training nurses was opposed by traditional nursing schools.

Baragar’s ultimate departure from the BHMD was the result of a conflict with staff who had joined the trade-union movement, including, ironically, graduates (and students) of the nursing program he had created. In July 1926 Baragar warned the deputy minister of public works about the newly formed Mental Hospital Workers’ Federal Labour Union No.33, whose members had requested that he recognize their organization and endorse their demands for shorter hours, increased pay, and better working conditions. Baragar, who lacked the authority to make changes that would require more funding from the province, sympathized with his employees and felt that the Manitoba government, headed by John Bracken*, ought to give them a fair hearing. Baragar’s first priority, however, was the welfare of patients, and he was strongly opposed to the idea of public-sector unions, particularly in hospitals. His attempts to undermine No.33 –which included appealing to the high calling of the nurses, suggesting that their motives were selfish, and pressuring them to sign a pledge that they would leave the union –alienated members of his staff.

The Reverend William Ivens*, an organizer of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowiski*] who had become an mla, took up the cause of the union, and the Bracken government subsequently appointed a royal commission to investigate the situation. Its report, issued in August 1928, largely exonerated Baragar and concluded that the hospital was well run. On the subject of the labour unrest, scholar Chris Dooley comments that while the training program benefited the BHMD, job prospects for its graduates were limited, and “mental nurses at the hospital in the 1920s evolved a culture of resistance to the long hours, poor working conditions and restrictive regulations of the training school.” Shortly after the report came out, Baragar, who had lost the confidence of many employees, took a leave of absence to do research in England. He never resumed his duties at Brandon.

Baragar resigned as medical superintendent in September 1930, and that same month he became Alberta’s inaugural commissioner of mental institutions and director of mental health. This position had been created in response to an incident that had occurred two years earlier at the Provincial Mental Hospital (PMH), formerly the Provincial Hospital for the Insane, near Ponoka: Arthur Hobbs, a patient, was beaten to death by a student attendant. An inquest led by judge Emily Gowan Murphy [Ferguson] was followed by a royal commission co-chaired by Clarence Hincks and psychiatrist Clarence Byrnold Farrar*. Their report led to the resignation of the hospital’s superintendent, Edleston Harvey Cooke. In 1918, Cooke had released patient James Oscar Triplett*, who went on a destructive rampage before being shot to death. The report recommended the establishment of a psychiatric-nursing school, the adoption of a more humanitarian approach to care, including the repudiation of restraints and seclusion, and the creation of a new office, that of provincial commissioner of mental health. The United Farmers of Alberta government led by John Edward Brownlee* acted on the last suggestion and then offered the position to Baragar, who was the ideal candidate.

Baragar began his tenure as commissioner by acquiring a Rockefeller Foundation grant (1930–33) to fund an acute-care psychiatric unit for 18 patients at the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton. He opened clinics in Lethbridge (1930) and Medicine Hat (1933), and added a psychiatrist to the travelling clinic in the Peace River district (1934). While fulfilling his duties as commissioner, he became a lecturer at the University of Alberta and served briefly as acting medical superintendent of the Ponoka facility. Scholar Mary Frances McHugh Abt notes that while his predecessor at Ponoka had a militaristic style, “Baragar appears to have made a deliberate effort to shift the focus to providing a more therapeutic environment for patients and toward improving the expertise and morale of the nursing staff.”

Baragar’s wife, Eugenie, who had urged him to accept the post in Edmonton, was in poor health, and she died shortly after they arrived there. The marriage had been a very happy one, and Baragar established the Blanche Eugenie Baragar Memorial Award at the BHMD to honour her. Now totally focused on his work, he was responsible for a series of firsts in Alberta: he implemented changes in treatment so that patients undertook useful work, hired an occupational therapist, and, in 1931–32, added recreational activities, entertainment, and social services. In 1931 Baragar began a program to train psychiatric nurses at the PMH in Ponoka, with Hilda Bennett, bscn (Bachelor of Science in Nursing), as instructor and Catherine Lynch, rn, as superintendent. A three-year curriculum was developed, and 30 women enrolled. Baragar promoted combined instruction in psychiatric and general nursing because he felt that staff needed to be sensitive to both the mental and physical health of patients. He next developed a postgraduate course in psychiatric nursing to prepare rns for supervisory roles. The programs were opposed by the University of Alberta and the Alberta Association of Registered Nurses, both of which saw themselves as gatekeepers to the nursing profession. Baragar appealed to George Hoadley*, the minister of health, and Hoadley authorized the two courses of study. The PMH then affiliated with hospitals in Edmonton and Calgary to enable students to become rns. Baragar also developed a six-month in-service curriculum for attendants. These programs would remain the standard in Alberta until the 1970s. As well, Baragar encouraged the placement of medical students in mental-health facilities to interest them in careers in psychiatry, and he was instrumental in opening more beds for patients.

In spite of all of the enlightened work that Baragar did in Alberta, his name has become primarily associated with sterilization. Like other medical practitioners of the time, such as C. K. Clarke, Charles John Colwell Orr Hastings, and Thomas Joseph Workman Burgess*, Baragar believed that, to ensure healthy future generations, it was necessary to discourage mentally or physically unfit people from procreating. When Brownlee’s United Farmers of Alberta government proposed in 1927 to legalize the sterilization of inmates of psychiatric hospitals, it was supported by Clarence Hincks, Jean H. Field, a member of the Board of Visitors, which oversaw the province’s mental-health facilities, and the United Farm Women of Alberta, which had advocated the policy for several years. When the Sexual Sterilization Act received royal assent on 21 March 1928, Alberta became the first jurisdiction in the British empire to enact such legislation.

The following year the board of examiners created by the act, which became known as the Eugenics Board, developed criteria for approving sterilizations; the operation could only be carried out with the consent of the patient or the patient’s responsible guardian. (This stipulation would be abolished by the Alberta government in 1937, the year after Baragar’s death.) Three procedures were performed in 1929. In a memorandum dated 27 Nov. 1930, Baragar summarizes a discussion held at Ponoka to define “classes of cases eligible for presentation within the meaning of the Act.” The document makes it clear that he not only supported the legislation, but was also in favour of extending it to include sex offenders and drug addicts “partly on account of the hereditary factors so frequently present and partly in the interest of possible children and of the state.” Baragar’s is the lead name on the first report on the implementation of the act, published in 1935. The report makes it clear that sterilization facilitated the discharge of patients, and notes that as of 15 June 1934, 414 cases had been presented to the board and 261 operations had been performed, with no fatalities or serious complications occurring. Statistics are provided, broken down by hospital, up to 31 Dec. 1933: there had been 98 sterilizations at the University of Alberta Hospital, 56 at the Calgary General Hospital, 24 at the Red Deer Municipal Hospital, 14 at Lethbridge’s Galt Hospital, and 14 at Ponoka’s Provincial Mental Hospital. The age range of the patients was 12 to 45, 77 per cent were under the age of 30, and nearly 70 per cent were women. Information is also provided in the report about the status of patients after they were sterilized, indicating that its authors had continued interest in their mental condition.

Charles Arthur Baragar made progress as commissioner, but he struggled with declining government funding, which resulted in overcrowding, staff shortages, and finally, in the fall of 1935, the abolition of his position. He then resumed his former post as medical superintendent of the Provincial Mental Hospital at Ponoka. In early 1936, while conducting mental-health clinics around the province, Baragar contracted an acute sinus infection and then influenza, which led to pneumonia. He died on 8 March, at 51 years of age. His successor at Ponoka, Randall Roberts MacLean, believed Baragar was depressed because the abolition of his post as commissioner had dealt “a shattering blow to his plans and aspirations for the future of Mental Health in the Province of Alberta and Canada.”

Charles Arthur Baragar is the author of “Prevention of mental breakdown,” Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene (Montreal), 3 (April 1921–January 1922), no.2: 55–64; he is the co-author, along with G. A. Davidson, W. J. McAlister, and D. L. McCullough, of “Sexual sterilization: four years experience in Alberta,” American Journal of Psychiatry (Baltimore, Md), 91 (1934–35): 897–913. The Faculty of Medicine Arch. at the Univ. of Man. (Winnipeg) has a small file of documents relating to Baragar (Biog. records coll., Baragar_CA). A photograph of Baragar is held by the Univ. of Alta Arch. (Edmonton), Acc. no.81-117-1-48. He can also be seen in a digitized composite portrait of the Provincial Mental Hospital’s graduating class of 1934 in the GA’s digital collection (digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/asset-management/2R3BF13IF53?WS=PackagePres (consulted 22 Sept. 2021)).

LAC, RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 416-13. M. F. McH. Abt, “Adaptive change and leadership in a psychiatric hospital” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alta, 1992). I. H. Clarke, “Public provisions for the mentally ill in Alberta, 1907–1936” (ma thesis, Univ. of Calgary, 1973). P. V. Collins, “The public health policies of the United Farmers of Alberta government, 1921–1935” (ma thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1969). C. P. A. Dooley, “‘When love and skill work together:’ work, skill and the occupational culture of mental nurses at the Brandon Hospital for Mental Diseases, 1919–1946” (ma thesis, Univ. of Man., 1998). Robert Lampard, Alberta’s medical history: “young and lusty, and full of life” (Red Deer County, Alta, 2008). R. R. MacLean, “Historical sketch: Dr. Charles Arthur Baragar, 1885–1936” (ms copy, 24 April 1963; available at PAA, GR1973.0116). Marg Moncrieff and Henry Matejka, “History of psychiatric nursing programs at Alberta Hospital School of Nursing Ponoka (1930–1989)” (typescript, June 1989). S. J. S. Peirce, “Charles Arthur Baragar, 1886–1936,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 93 (1936–37): 754–56. Kurt Refvik, A centennial history of the Brandon Asylum, Brandon Hospital for Mental Diseases, Brandon Mental Health Centre (Brandon, Man., 1991). United Empire Loyalists’ Assoc. of Can., “The Baragars of Manitoba,” in The loyalists, pioneers and settlers of the west: a teacher’s resource: www.uelac.org/education/WesternResource/401-Baragars.pdf (consulted 6 July 2017).

Cite This Article

Adriana A. Davies, “BARAGAR, CHARLES ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baragar_charles_arthur_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baragar_charles_arthur_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Adriana A. Davies |

| Title of Article: | BARAGAR, CHARLES ARTHUR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |