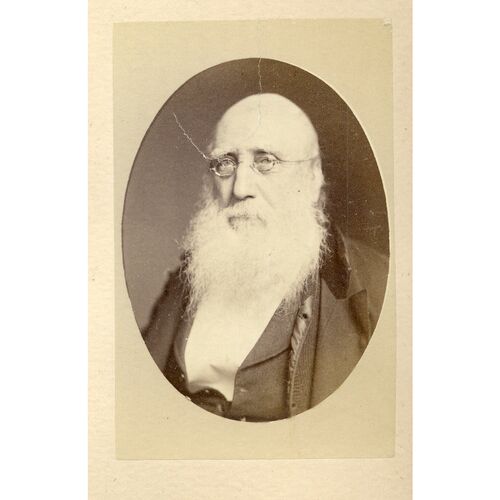

AUBIN, NAPOLÉON (baptized Aimé-Nicolas), journalist, publisher, playwright, and scientist; b. 9 Nov. 1812 at Chêne-Bougeries, a commune in the suburbs of Geneva (Switzerland), son of Pierre-Louis-Charles Aubin, a potter, and Élisabeth Escuyer; d. 12 June 1890 at Montreal, Que.

Little is known of Napoléon Aubin’s childhood. We may surmise that during his adolescence at Geneva, the environment, his own temperament, and perhaps also his reading inclined him towards the progressive ideologies of his time and gave him an interest in natural science. He left school when he was about 16, and set out for America in August 1829. The reasons for his departure are open to conjecture. The political and religious discussions which characterized his native milieu, and the attraction of America, a “land of success and freedom,” no doubt influenced his decision. From 1829 to 1835 Aubin stayed in the United States. But, disappointed in the American way of life, he turned to Canada. He sent to La Minerve of Montreal articles in which he affirmed his support for the Patriote party. On his arrival in Canada, Aubin spent some months in Montreal, but at the end of October 1835 he settled in Quebec City and devoted himself to journalism. In addition to contributing to L’Ami du peuple, de l’ ordre et des loisof Montreal, he was editor of Le Canadien of Quebec City from 1847 to 1849 and started several periodicals in Quebec City, whose brief lives did not dishearten him: Le Télégraphe (22 March–3 June 1837), Le Fantasque (published irregularly 1 Aug. 1837–24 Feb. 1849), Le Standard (November 1842), Le Castor (7 Nov. 1843–22 June 1845), Le Canadien indépendant (21 May–31 Oct. 1849), and La Sentinelle du peuple (26 March–12 July 1850). He also published, in 1842, the first newspaper in Canada devoted to working-class interests, the People’s Magazine and Workingman’s Guardian (Quebec). From 1853 to 1863 Aubin was again in the United States, then returned to Quebec, his adopted city. There he contributed to La Tribune in 1863 and 1864, but in the latter year he retired to Longueuil, Canada East. In 1865 he launched another newspaper, Les Veillées du Père Bon Sens (Montreal) (1865–66 and 1873). In 1866 he finally settled in Montreal, and in 1868–69 wrote for Le Pays. His last contribution to the press was in 1876; at that time he was publishing in Le National, of which he had been editor from 1872 to 1874. A journalist by inclination, Aubin nevertheless earned his livelihood through his scientific and technical knowledge. In the end, the technician would overshadow the ideologue: he was appointed gas inspector for the city of Montreal in 1875, and he travelled all over Canada as a city lighting adviser.

Aubin is remembered particularly for his contributions to the life of his society as journalist, poet, story-teller, publisher, and playwright. His published journalism is impressive. Although in the 1830s he was in sympathy with the national cause, Aubin was sometimes hard on the leader of the Patriote party. He saw Louis-Joseph Papineau* as a tyrant and a coward, who was dragging the country on a dangerous downward path. Like Étienne Parent* he felt the Patriotes were going too far, and again like Parent warned the population on the eve of the uprising in 1837 to be on guard against its political leaders. Le Fantasque was then in its early days. Aubin drew the material for its satirical prose from the extremists, bureaucrats, and Patriotes. In the disturbed atmosphere of the late 1830s, he managed to bring a smile to faces that showed the strain of political conflict.

Well fitted to be a man of the opposition, Aubin kept an eye on the activities of Lord Durham [Lambton*]. He might approve of the amnesty granted by the British lord, but he found him a little too fond of fashionable gatherings. Balls were frequent at the governor’s château. Did Durham work? Teasing aside, Aubin did offer the chief of state food for thought. With the governor in mind, he gave a sympathetic description of French Canadians. They must not be confused with their leaders. In Aubin’s opinion, Durham in spite of everything remained insensitive to their grievances.

A liberal and a democrat, Aubin’s assessment of the governors after the union was determined by their rejection or acceptance of the principle of ministerial responsibility. Charles Edward Poulett Thomson*, who carried through the project of union, was censured on several occasions by the editor of Le Fantasque. Tempered with irony, the criticism of the crown’s representative was nevertheless severe. “When I think of how we are governed by a mere poulet [pullet], I begin to get la chair de poule [gooseflesh].” The colony’s merchants saw it as logical that Canada West’s debt should be shared by the taxpayers of the two united provinces. The nationalists of Canada East did not see it this way. Aubin made himself their spokesman in depicting the governor as a despoiler of the collective wealth of the French Canadians. Mixing irony with malice, he wrote: “When the knights of old went off to war, they were protected by their écus [a shield or coin]. Master Thomson launches forth covered with ours.” Commenting on a rumour that the governor had “rendu l’âme [died, or yielded up his soul],” he remarked: “This is surely absurd. He would have quite enough trouble to rendre all he has taken from us let alone that [âme] which he never had.” Sir Charles Bagot*, given a cool welcome by the humorist, found favour when Aubin perceived that the new governor had been won over to the idea of responsible government. On the other hand, Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe* was censured because he undid his predecessor’s work.

The political ascension of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* did not please Aubin. As the statesman moved closer to power, the journalist applied himself to rehabilitating Papineau, his favourite target before the armed uprising. Aubin considered La Fontaine intransigent when he refused the post of attorney general of Canada East in 1842 unless Robert Baldwin* was appointed to the Executive Council. Once in power La Fontaine became to him an intriguer who had wanted to climb to the leadership of the Patriote party. Not that Aubin disapproved of all the political moves made by the new leader of the French Canadians. The resignation of La Fontaine and Baldwin from Metcalfe’s council in 1843 met with his full approbation; in his view the principle of responsible government must be upheld against the claims of authoritarian governors. But the principle of ministerial responsibility having been put into effect in 1848, Aubin argued that the Reform leader was now motivated by self-interest.

In the end, it was the Rouges who were most in line with Aubin’s ideas. From 1847 to 1849, as editor for Le Canadien, he put forward his views on economic and social reform. He advocated land settlement efforts as a means of checking emigration to New England. Without condemning those who had carried on the struggle of the French Canadians solely on the basis of survivance, he considered that their full development could come only through economic emancipation. Deploring the lack of French-speaking entrepreneurs, he preached thrift and became a promoter of the textile industry. His social theories about methods of production were at times akin to some current in the Europe of 1848. He suggested enterprises financed by both workers and entrepreneurs, all French Canadians, who would share in the profits.

At the end of the 1840s, Aubin’s political ideas were identical with those of Papineau and L’Avenir (Montreal). Had not the journalist himself drafted the Manifeste adressé au peuple du Canada par le Comité constitutionnel de la réforme et du progrès (Quebec, 1847)? It was with Papineau’s support that Aubin left Le Canadien to start Le Canadien indépendant in 1849. In the columns of the new paper, separatism and annexationism had pride of place. To those who objected that his association with the annexationists was strange, Aubin replied that it was necessary to forget the past and redirect energies. Would not annexation to the United States carry the risk of eventual assimilation of the French Canadians? Aubin did not believe so. The local legislature would see that the national identity was protected. And if that did not happen, was it not better to set a high value on political and social progress, even if this might lead to the disappearance of the nation itself? In La Sentinelle du peuple, which replaced Le Canadien indépendant, Aubin continued to serve as spokesman for Papineau’s political ideas, although he refused to back Papineau’s opposition to the abolition of the seigneurial régime. On the other hand, he would unfailingly defend annexationism and loyalty to the political principles of the Rouges. Moreover, he would be president of the Institut Canadien of Montreal in 1869. Like many French Canadian Liberals, he considered confederation a plot hatched by the financial backers of the Grand Trunk, in league with scheming and venal politicians. The failure to offer a referendum on the 1867 constitution was to him a serious violation of the democratic principles he had always defended. As a nationalist, he was disturbed that French Canadians would be a minority in the new country. For him, annexation would have been preferable to the arrangement of 1867.

Aubin’s career reflects the climate of suspicion, denunciation, and contempt for freedom of thought that prevailed during the early years of the union period. For publishing a poem by Joseph-Guillaume Barthe* dedicated to the political prisoners of 1837–38 deported to Bermuda, Aubin served 53 days in prison. Detention did not silence him. In the issue of 8 May 1839 of Le Fantasque, he spoke ironically about living conditions in a prison cell. Between 9 July and 1 October, Aubin published in the paper a short story entitled “Mon voyage à la lune.” He used its plot as a cover for political and social criticism. “I dare not say anything more at the moment; people are so sensitive that they find allusions in everything. . . . If I laugh about an ass, Mr. Robert Symes [deputy chief of police at Quebec, well known for his contempt for French Canadians] insists that the ass is his emblem. . . . If I speak about decent people, the police imagine I am talking about them. . . . One can easily understand that with such limited freedom of the press a writer’s only recourse is to . . . fly to the stars rather than lament longer on a prejudiced earth where in order to please and to live one must crawl . . . and lick the spurs of those who believe themselves great because they have their greatness proclaimed so often, who bear their rights in their scabbards and keep their hearts in their pockets.”

In 1839, Aubin established a troupe of actors who played Voltaire’s La mort de César at the Théâtre Royal of Quebec, as well as two short pieces of his own, Le soldat français and Le chant des ouvriers. The authorities became uneasy. For the Quebec Gazette, Voltaire’s play was a revolutionary manifesto. The works of Aubin were judged subversive. Disturbed, Thomas Ainslie Young*, the chief of police of Quebec, wrote to the governor: “The entire performance had a decidedly political character, and its aim was to arouse the passions of the audience against the established order.” At Young’s request, the city council forbade any performance after 11 o’clock in the evening, so that Aubin’s troupe ceased to perform for a while. The few plays by secondary authors which were put on in 1841 were harmless.

In 1842 Aubin published Le rebelle, histoire canadienne, by the Baron de Trobriand. According to the publisher’s preface, the novel was intended to perpetuate the memory of the Patriotes. As with the theatrical performances staged by Aubin, the police were on the watch: a seller of Le rebelle was arrested in Montreal. At a time when the liberal nationalism of 1837 was being eclipsed by the initiative of those in power, a historian such as François-Xavier Garneau* could have found no better ally than Aubin. It was certainly no accident that he undertook to publish the first two volumes of the great historian’s national history.

Versatility was one of Aubin’s salient characteristics. His liking for science was not the least curious facet of this unusual individual. He gave public courses and lectures in popular science, and was one of the first professors of the Quebec School of Medicine (founded in 1845) where he was responsible for teaching chemistry. Two popular works on chemistry were written by him: La chimie agricole mise á la portée de tout le monde . . . (Quebec, 1847) and a Cours de chimie (Quebec, 1850). He gave his name to a widely used invention: during the decade he spent in the United States, from 1853 to 1863, he perfected a gas-lighting process which was patented in Canada, the United States, England, and France. The device was employed by several cities in North America, and was written up in an article in Scientific American (New York) in 1858. The journal explained how the device worked and pointed out that the invention was well thought of by its users.

Aubin is a fine example of an immigrant who succeeded, as a result not only of his talent but also of his adaptability in a cultural context quite foreign to his native environment. He was baptized a Calvinist, but kept it secret all his life. He found a place in the Roman Catholic community when, on 9 Nov. 1841 in the Saint-Roch church in Quebec City, he married a girl from an established bourgeois family, Marie-Luce-Émilie Sauvageau, whose father, Michel-Flavien, was a notary in the city. It was a hasty marriage, the bride being pregnant, so there was no inquiry into Aubin’s religious persuasion. The couple’s four children were baptized Roman Catholics. The fact that a Presbyterian minister, Daniel Coussirat, delivered Aubin’s funeral oration, and that he was buried in a Protestant cemetery, must have surprised many people. These events no doubt confirmed the conviction in uncompromising clerical-nationalist circles that Protestantism and liberalism were two sides of one and the same heresy.

Aubin’s life in Canada somewhat weakens the myth of the xenophobia of French Canadians. As a man of the opposition, he might often have been reproached for not being a French Canadian. Joseph-Édouard Cauchon made a stab at it, but he did not come off best in the bitter controversy in which the two men engaged. The majority of the intellectuals of Aubin’s generation admired his talents without holding his origins against him, for at the very outset he made the national aspirations of his adopted country his own. The young generation of liberal intellectuals of the 1840s no doubt drew some of their vision of collective destiny from him. Easy of manner, Napoléon Aubin was a friend of many outstanding personalities of his day: Ludger Duvernay*, Philippe-Joseph Aubert* de Gaspé, Joseph-Guillaume Barthe, Étienne Parent, James Huston*, Louis-Joseph Papineau, and Joseph Doutre, to name only a few. At his funeral, the presence of an imposing number of prominent people – including diplomats, for Aubin had been honorary consul of Switzerland since 1875 – was evidence of the esteem he had won for himself among his compatriots.

[For a fuller understanding of the work of Napoléon Aubin the following studies by Jean-Paul Tremblay are useful: “Aimé-Nicolas dit Napoléon Aubin, sa vie et son œuvre” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, Québec, 1965), and À la recherche de Napoléon Aubin (Québec, 1969). s.g.]

Beaulieu et J. Hamelin, Journaux du Québec. Bernard, Les Rouges. Monet, Last cannon shot.

Cite This Article

Serge Gagnon, “AUBIN, NAPOLÉON (baptized Aimé-Nicolas),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aubin_napoleon_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aubin_napoleon_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Serge Gagnon |

| Title of Article: | AUBIN, NAPOLÉON (baptized Aimé-Nicolas) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |

![[Napoléon Aubin] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Napoléon Aubin] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.4453.jpg)