Source: Link

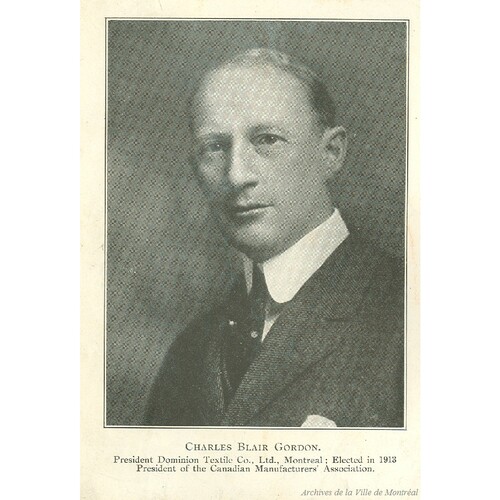

GORDON, Sir CHARLES BLAIR, businessman and office holder; b. 22 Nov. 1867 in Montreal, son of John Gordon and Jane (Jeanie) Roy; m. there 19 April 1897 Edith Annie Brooks, sister of Harriet Brooks, and they had three sons; d. there 30 July 1939 in Montreal.

Charles Blair Gordon’s father was the proprietor of a wholesale dry-goods firm in Montreal. Gordon was educated at public school and at the High School of Montreal. At age 19 he took his first job as a clerk in a dry-goods store, McIntyre, Son and Company. Two years later he became a shipping clerk for a dry-goods wholesaler, J. P. Black and Company. Then, about 1891, he formed his own business, the Standard Shirt Company. It prospered and in April 1895 he obtained letters patent from the federal government “to manufacture, buy, sell and deal in shirts, collars, haberdashers supplies and men’s, women’s and children’s clothing of every description, throughout the Dominion of Canada.” The firm had a capital stock of $200,000 in 2,000 shares; Gordon and his partners took up 50 per cent of it, with Gordon himself holding 343 shares. In 1901 the capital stock was increased to $1 million and the firm’s powers were extended to allow it to acquire shares in other companies, act as printers of materials for its business, and acquire plants, machinery, and workers as necessary.

A picture from 1903 shows the company offices and plant in five multi-storied buildings occupying a five-acre site on de Lorimier Avenue. The company was said to generate its own power. It employed nearly 1,200 workers, supplied much of the domestic market, and exported some products to South Africa and Australia. Gordon quickly gained a reputation in the city as a rising young businessman. In 1904, at age 37, he joined a syndicate which brought together four companies, Dominion Cotton Mills Company Limited, Merchants’ Cotton Company, Montmorency Cotton Mills Company, and Colonial Bleaching and Printing Company, to form the Dominion Textile Company early the following year. All were on the brink of failure. Barbara J. Austin, the historian of Dominion Textile, has characterized the merger as “a desperate move” to reduce competition in the cotton trade and bring some stability to the industry. Dominion Textile’s syndicate was led by David Yuile*, who had successfully organized other mergers, including the Diamond Flint Glass Company, and was widely respected in Montreal’s business community for his financial acumen. Gordon borrowed to purchase his 496 shares at $100 each. He holds, with Yuile, the title of company founder because, as second vice-president and managing director, he was given the task of launching and running the new enterprise. Yuile was named president and Louis-Joseph Forget* first vice-president. Gordon supervised day-to-day operations and carried out the decisions of the company’s executive of which he, Yuile, Forget, Herbert Samuel Holt*, Henry Vincent Meredith*, Senator Robert Mackay, John P. Black, David Williamson, and others were members. In 1909, after Yuile’s death, the board of directors elected Gordon president.

Canada’s cotton industry was centred in Quebec, where more than 60 per cent of the workers were employed and 66 per cent of the goods produced. On its formation, Dominion Textile immediately became the largest company in the trade, producing 45 per cent of the nation’s cotton textiles. Its largest Canadian competitor was the Canadian Colored Cotton Mills Company Limited (renamed Canadian Cottons Limited in 1910). External competition came from British mills, whose wares were subject to a preferential tariff of 15 to 17½ per cent but were still competitive in Canada. A prohibitive tariff of 40 to 50 per cent on cotton materials manufactured in the United States effectively barred them from the Canadian market. Dominion Textile also had close ties with the Penman Manufacturing Company Limited, the largest producer of woollen articles in Canada, whose president, David Morrice, was a member of the Dominion Textile syndicate and president of Canadian Colored Cotton. When Morrice died in 1914, Gordon became president of Penman’s as well.

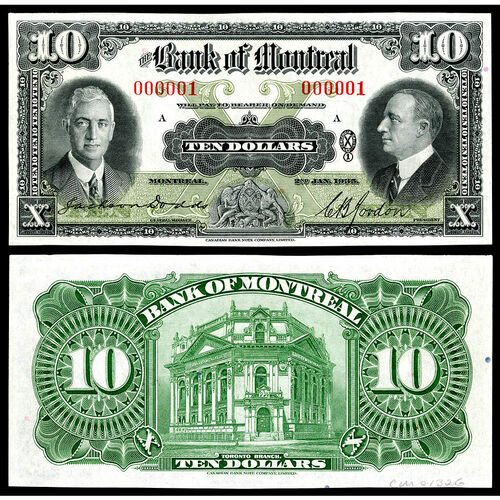

Dominion Textile’s traditional markets for its cotton fabrics were dry-goods stores (there were almost 300 in Montreal alone), and those individuals who sewed for their own use. But in the pre-war years increasing amounts of Dominion Textile’s products were sold to two emerging markets, firms such as Gordon’s own Standard Shirt Company which produced ready-to-wear clothing, and department stores such as Henry Morgan and Company Limited in Montreal. Under Gordon’s leadership, Dominion Textile grew; at his death in 1939 it would employ more than 6,000 workers and hold assets of $50 million. As the company expanded, Gordon’s influence among Montreal’s business titans burgeoned. In 1909 he became a director of Molsons Bank. By 1911 he was ranked a millionaire by the Montreal Daily Star. He joined Holt, Sir Hugh Montagu Allan*, and Charles Rudolph Hosmer as founders of the prestigious Ritz-Carlton Hotel, the construction of which started that year. A year later he was elected a director of the Bank of Montreal. In 1913 Gordon led a syndicate to merge Diamond Flint Glass, Canadian Glass, Sydenham Glass, Manitoba Glass, and Jefferson Glass into the new Dominion Glass Company Limited. The following year he became president of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association.

World War I triggered a boom in Canada’s textile industries. Initially small, then huge, orders for cloth for uniforms, tents, and dozens of other supplies for the Canadian Expeditionary Force flowed into Dominion Textile. In 1917, when the United States entered the war, still more requests came for material for uniforms. Gordon’s personal involvement in the war effort was diverse. He joined Mackay, Meredith, and Huntley Redpath Drummond to pay for equipment for the Canadian Machine-Gun Corps. As a director of the Bank of Montreal, he advised his government on credits established by the British government to finance war procurements in Canada. And he lent his yacht, fully manned, to the Royal Canadian Navy for coastal patrol service for the duration of the war. All these activities were eclipsed on 1 Dec. 1915 when he was appointed vice-chairman of the newly established Imperial Munitions Board; under the direction of Joseph Wesley Flavelle, it was the sole purchasing agency in Canada for the British Ministry of Munitions. Gordon’s hopes that he could serve on the board and remain active in Dominion Textile vanished almost immediately as he and Flavelle found themselves working full-time and overtime for the IMB. At the company, Gordon shared strategic direction during the war with Holt, while the day-to-day operation of the firm was turned over to Gordon’s trusted general manager, Francis Galvin Daniels. In Ottawa, he and Flavelle formed the inner executive of the IMB with David Carnegie, head of the board’s technical department, and Frederick Perry, who supervised the board’s finances and relations with the Ministry of Munitions in London.

The IMB had inherited from Sir Samuel Hughes*’s Shell Committee orders for artillery shells worth more than $282 million, contracts with over 400 different factories, and supervision of the manufacture of tens of millions of shells and ancillary parts. Its most serious problem was acquiring time and graze, or percussion, fuses for the shells produced by its factories. There was no capacity to create and assemble these precision parts in Canada, and contracts with American companies had proved dismal failures. The problem was given to Gordon to solve. He recommended that fuse manufacturing be done in Canada. The IMB set up its own factory in Verdun (Montreal) to make the delicate time fuses. Skilled workmen and supervisors were quickly brought over from Britain to train Canadian workers. British Munitions Limited, the IMB’s first “national factory,” was open for business by the spring of 1916. The last order from Britain, for 3,000,000 fuses, came in 1917 and the last fuses were shipped in May 1918. British Munitions was then converted by the IMB into a shell-manufacturing facility.

In 1916 Gordon had dealt with the increasingly serious problem of labour shortages in munitions factories across the country by persuading the army to temporarily release enlisted men from training or even from the front for duty in the factories. Another issue consisted of sorting out the commitments of companies such as the Algoma Steel Corporation to provide both material for munitions and replacement rails in Canada for overused railway lines. In addition, Gordon played a role in establishing a school for air force trainees in Canada and setting up a national factory, Canadian Aeroplanes Limited in Toronto, to build aircraft [see Sir Frank Wilton Baillie*].

Gordon, with his wife Edith, left New York in April 1917 on an IBM mission to Britain. After several days at sea, the ship entered the critical zone in the recently opened submarine war launched by the German navy. “We had an exciting day,” Gordon wrote to Flavelle after seeing the wreckage of several boats and flares from others in distress. “Nobody went to sleep last night & there were a good many scared people on board.” Their own vessel had been ordered not to stop and it reached Britain safely with an escort of several destroyers.

In late June 1917 Gordon returned to Ottawa and almost immediately left the IMB to become deputy to Lord Northcliffe, the head of the British War Mission in Washington, D.C. Gordon was the representative of the ministry of munitions and the director of war supplies for the United Kingdom, dividing his time between Washington and New York City. He greatly missed Ottawa and the IMB; he told Flavelle in September that his work “with you at Ottawa was the pleasantest business experience of my career” and “my present job is anything but congenial at times.” Gordon disliked working with his British colleagues in general and with Northcliffe, whom he termed “a mount[e]bank,” in particular. When Northcliffe left in November 1917, he was replaced by Lord Reading. The situation was no better. Reading brought a group of inexperienced subordinates with him from Britain and ignored Gordon’s years of experience in munitions supplies. Hurt but resigned to his fate, Gordon wrote in 1917 that he was trying to follow Flavelle’s advice to “keep an even temper in most exasperating positions” and in 1918 that he would “serve the Government to the best of my ability” until the war was over. In the end, there was little satisfaction but there were rewards: he was made a knight commander of the newly formed Order of the British Empire in 1917 and the following year was promoted knight grand cross.

At the end of July 1919 Gordon was still dividing his time between Dominion Textile in Montreal and the British ministry of munitions in New York. As peace talks got under way at Versailles, France, and the Canadian government struggled with reconstruction plans at home, he was also appointed chairman of the Canadian Trade Commission, which had been created by order-in-council on 6 Dec. 1918. His job, together with that of Lloyd Harris who headed the Canadian Trade Mission in London, was to develop markets for Canadian exports in post-war Europe. They urged Ottawa to offer each of the governments of Romania, Serbia, and Greece – the three best prospects, selected by Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden – $50 million in credits to purchase Canadian exports. A nervous and cautious Department of Finance cut the credits for Romania and Greece in half and gave nothing to Serbia, weakening the initiative. Gordon also tried to get the Canadian government and Canada’s banks to cooperate in establishing a financial and credit corporation to stimulate trade, but that effort also met with timid responses. In 1921 Prime Minister Arthur Meighen* shut down the Canadian Trade Commission. Finally, there was one more assignment for Gordon. In February 1922 Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* appointed him and Édouard Montpetit* Canada’s representatives at the Genoa Conference for the Economic and Financial Reconstruction of Europe, to be held in April and May in Italy.

Then it was time to return to the handsome home he and his wife occupied on Queen Mary Road in Côte-des-Neiges (Montreal) and to Dominion Textile. He also possessed Torridon, an estate in the western Highlands of Scotland, which he had purchased about a decade earlier. By now, Gordon was recognized as a leader among the elite of the city’s business community. In 1927 he was elected president of the Bank of Montreal to replace Meredith, who was moved to the position of chairman of the board of directors’ executive committee. Gordon resigned the presidency of Dominion Textile and was succeeded there by his trusted general manager, but when Daniels died of cancer in 1933, Gordon returned to the leadership of Dominion Textile. Each workday morning his chauffeur would drive him to his office there; he would pore over the company’s account book and then walk to his office at the Bank of Montreal, where he would spend the remainder of the day. The bank’s historian, Merrill Denison*, writes that Gordon was “one of the most energetic presidents in its history.” Characteristically, Gordon made a point of getting to know personally all the managers of the bank’s major branches in Canada and abroad. At the outset of the Great Depression in 1929, Gordon followed the consensus of contemporary economic wisdom. “Fundamental conditions are sound,” he told the bank’s shareholders at the annual meeting, “and there is no reason for apprehension as to the ultimate future of Canada.” At Dominion Textile, although Gordon closed three old mills during the 1930s, he was determined not to lay off huge numbers of people. Instead, most had their work reduced to three or four days. The men and women had less pay but continued to earn wages. The firm continued to expand into new lines such as rayon textiles and automobile-tire cord.

Shortly before the beginning of World War II, on 27 July 1939, Gordon returned to Montreal from business in England. At home he suddenly became unwell and was taken to the Royal Victoria Hospital. There he died at age 71. His passing was front-page news in major papers across Canada. The lead editorial in the Gazette (Montreal) the next morning credited him with putting “the textile industry in Canada on its feet” and praised him as “a genuine patriot.” His funeral, held at Erskine and American United Church in Montreal, was attended by hundreds of colleagues and friends from Canada’s business, financial, and government communities. He was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery in Outremont (Montreal).

Charles Blair Gordon was an able and ambitious man. Under his initiative and leadership, the manufacture of cotton textiles flourished in Montreal and the city became the industry’s capital in Canada, supplying markets across the dominion and producing goods for export. That initiative and leadership caught the attention of Flavelle when he became head of the IMB. As Flavelle’s trusted colleague, Gordon applied his business skills to the multiple tasks of the board and in the later stages of the war he was a key figure in Britain’s munitions-purchasing program in North America.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S68, 19 avril 1897; CE601-S121, 23 févr. 1868. LAC, R1008-8-3, 2652; R1449-0-5; R6113-0-X. Gazette (Montreal), 31 July 1939. Ottawa Citizen, 31 July 1939. B. J. Austin, “Life cycles and strategy of a Canadian company: Dominion Textile, 1873–1983” (phd thesis, Concordia Univ., Montreal, 1985). Michael Bliss, A Canadian millionaire: the life and business times of Sir Joseph Flavelle, bart., 1858–1939 (Toronto, 1978). The book of Montreal: a souvenir of Canada’s commercial metropolis, ed. E. J. Chambers ([Montreal, 1903]). R. C. Brown, Robert Laird Borden: a biography (2v., Toronto, 1975–80). R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974). Steve Carter, “Torridon & Shieldaig: in the western Highlands of Scotland”: www.stevecarter.com/ansh/history.htm (consulted 23 Nov. 2009). Merrill Denison, Canada’s first bank: a history of the Bank of Montreal (2v., Toronto and Montreal, 1966–67), 2. Directory, Montreal, 1891–96. Dominion Glass Company, Telescope (Montreal), 1, no.7 (May 1973), Special issue (Dominion Glass celebrates 60th). P. E. Rider, “The Imperial Munitions Board and its relationship to government, business, and labour, 1914–1920” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1974).

Cite This Article

Robert Craig Brown, “GORDON, Sir CHARLES BLAIR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_charles_blair_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_charles_blair_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Craig Brown |

| Title of Article: | GORDON, Sir CHARLES BLAIR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | January 23, 2025 |