As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

Gordon, Charles William (also known as Ralph Connor), Presbyterian minister, author, military chaplain, and office holder; b. 13 Sept. 1860 in Indian Lands, Glengarry County, Upper Canada, son of the Reverend Donald (Daniel) Gordon, a minister of the Free Church, and Mary Robertson, a sister of Margaret Murray*, Andrew*, and Joseph Gibb* Robertson; m. 28 Sept. 1899 Helen Skinner King in Toronto; they had one son and six daughters; d. 31 Oct. 1937 in Winnipeg.

When Charles William Gordon was ten, his family moved to Harrington in Zorra Township, Ont. He attended Harrington Public School and then St Marys High School, where the classicist William Dale* instilled in him a love of language and literature. In 1879 he entered University College, Toronto; he graduated in 1883, obtaining a ba in classics and English with first-class honours. The next year, after teaching classics in high school, he began to study for the Presbyterian ministry at Knox College, Toronto. Knox required that its students work in the mission field, so Gordon spent the summer of 1885 at the Chesterville station near Cartwright, Man., where his love of the west was kindled. His first published work, “Jottings from a missionary’s diary,” based on his experience there, appeared in the November 1885–April 1886 edition of the student-run Knox College Monthly (Toronto), of which he was for a time co-editor with James Alexander Macdonald*. When he heard James Robertson* (no relation), superintendent of missions in the northwest for the Presbyterian Church in Canada, speak at St Andrew’s Church in Toronto and call for devoted and energetic men who could meet the challenges posed by the frontier, his enthusiasm for missionary work was further cultivated.

After graduating from Knox in 1887, Gordon spent a year at the University of Edinburgh, where he came under the liberalizing influence of the leading modernist theologians in Scotland, including Alexander Whyte and Marcus Dods. On his return he assisted his father, who was ill, with his pastoral duties. His mother’s death in 1890 left him temporarily unsettled, but he soon made the momentous decision to accept the call of the west. He was ordained by the presbytery of Calgary in June 1890 and served in the Banff–Canmore mission field for three years. Gordon had been asked by Robertson to take over the West End mission in Winnipeg in 1892. After spending some time in Scotland brushing up on his studies and canvassing for clergy and funds, he finally took Robertson’s offer and settled in Winnipeg in August 1894. The mission became a self-sustaining parish, St Stephen’s Presbyterian, soon after his arrival.

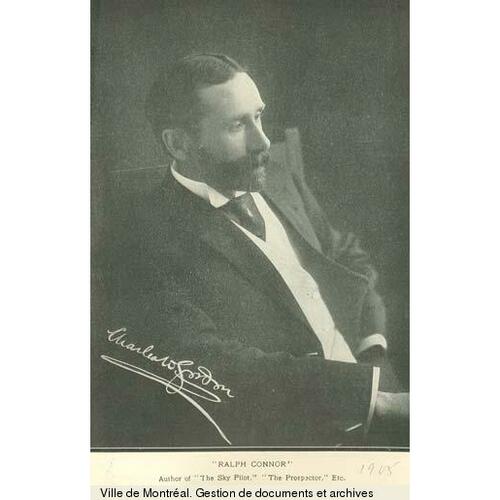

Gordon continued to work with Robertson, who had become his mentor, to attract the people and resources necessary to develop the Presbyterian Church in the west. Furious about the General Assembly’s decision in 1896 to cut funds for western missions, Gordon wrote about the problems facing churches in the region. Initially, he submitted fact-laden reports to Macdonald, now editor of the Westminster (Toronto), a Presbyterian journal. Macdonald refused to publish them and prodded Gordon to write articles that captured his personal experience of missionary life. Gordon responded by submitting a story about a missionary whose explanation of the meaning of Christmas moved the most hardened and sinful man in a lumber camp to fall to his knees in prayer and repentance. Macdonald decided that the piece was too long, so Gordon rewrote it as a story in three chapters, the first of which was published in January 1897. According to Gordon, Macdonald telegraphed to ask how he wanted to sign his contribution. Gordon, as secretary of the British Canadian Northwest Missions, decided on “Cannor,” a partial abbreviation of Brit.Can.Nor.West Mission. The telegraph operator changed it to the more likely spelling of Connor. Macdonald then added the first name Ralph. Gordon would use the pen name throughout his life. He agreed to a pseudonym because writing fiction was not considered a respectable persuit for a clergyman. At this time, Gordon was courting Helen Skinner King, the daughter of an eminent theologian, the Reverend John Mark King*, who was opposed to the relationship. Gordon did not want to further alienate King in his quest for his daughter’s hand by openly engaging in such a questionable activity. By March 1898 it was generally known that Ralph Connor was the Winnipeg minister Charles Gordon. The author was easily recognized in Presbyterian circles, since the early Connor stories contained a great deal of autobiographical detail from Gordon’s own experiences as a missionary in western Canada.

Reader response to “Christmas Eve in a lumber camp” was so enthusiastic that Macdonald encouraged Gordon to write more instalments. These short stories were strung together as a novel, and in 1898 the Westminster Company Limited of Toronto published it as Black Rock: a tale of the Selkirks under the name Ralph Connor. Three additional books followed quickly and Gordon became a literary sensation. The sky pilot: a tale of the foothills (1899) describes the work of a young minister among cowboys, The man from Glengarry: a tale of the Ottawa (1901) draws on the author’s memories of life in pioneer Ontario, and Glengarry school days: a story of the early days in Glengarry (1902) is an idyll about growing up in the backwoods of eastern Ontario.

Gordon was more interested in using novels to reach people with his message about the challenges facing the church on the frontier than in developing his literary style. Narrative became part of his ministry. His stories were sermons dressed in modern garb and written for a wider audience than one that could be reached from the pulpit. Religious themes, such as the prodigal son, the purpose of human suffering, and especially the need for forgiveness, permeated his early fiction, demonstrating to readers the transformative power of the Christian gospel. The tales, however, were far from being theological tracts. In fact, they were much closer to adventure stories, high in drama and pathos, and his characters included a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer as well as clergymen. The missionary protagonists presented the gospel with straightforward simplicity, in a manner similar to that used by Jesus as recounted in the Bible. His heroes were prototypes of muscular Christianity: strong, athletic, energetic, adventurous, courageous, loyal to God, steadfast in their commitment to the church, and at times violent. Gordon hoped that his fiction would have an uplifting influence on a popular culture that seemed dangerously out of touch with Christian teaching. For some of his novels he would later grant the rights for both stage and film productions in the hope that his stories would be instrumental in elevating theatre and cinema, which he believed had fallen prey to sensational influences of dubious moral character. His novels gave him a pulpit with great reach and influence. By 1914 he had published nine best-selling novels under the Connor name and at least 100,000 copies of each had been purchased. According to royalty reports, over 1.6 million copies of his books had been sold in the combined markets of Canada, the United States, and Great Britain.

While Gordon’s fame as a writer grew in the first decade of the 20th century, his reputation as a crusading clergyman in Winnipeg and throughout the province had also spread. He was prominent in the temperance movement in Manitoba and he spearheaded the ban-the-bar movement. He was active in the Lord’s Day Alliance, led from 1900 to 1907 by his friend the Reverend John George Shearer*. As president from 1910 of the Manitoba branch of the Moral and Social Reform Council of Canada (renamed the Social Service Council of Canada in 1913) [see Shearer], he was an outspoken political opponent of Premier Rodmond Palen Roblin and his Conservative administration. Along with the Reverend Salem Goldworth Bland* of the Methodist Church of Canada, he persuaded Tobias Crawford Norris and the Manitoba Liberal Party to adopt the motto “ban the bar” as a cornerstone of the Liberal platform for the 1914 provincial election. Despite Gordon’s deepening involvement in partisan politics, in the Manitoba Free Press of 8 June he claimed that, for him, advocating temperance was “not a question of party politics, but of ethics, of patriotism, of religion.”

According to Gordon, urban society offered sinful distractions, especially for bachelors and young men, and he was concerned that too few men attended church. The muscular Christianity of his novels was intended to counter what critics perceived as the overly feminized atmosphere of the church. Moreover, Gordon thought that a church building had to be more than a place of worship – it had to be a centre of fellowship and activity for both men and women. He oversaw the transformation of St Stephen’s from a modest wooden structure into a large institution with an auditorium-like sanctuary, a gymnasium, and an adjoining church-house that facilitated the activities of numerous groups, including associations for men who were too often overlooked in the church’s ministry. Between 1897 and 1902 the small suburban congregation had increased by almost 200 to nearly 300 members owing to Winnipeg’s booming population as well as Gordon’s growing celebrity. In 1902 a new church building was constructed, but by 1908 an extension was necessary as membership continued to soar, reaching 565. By 1911 St Stephen’s boasted over 1,000 members.

Gordon was witness to the huge influx of immigrants into Winnipeg’s North End. Like many social progressives of the day, he thought that these foreigners should be assimilated into the Canadian way of life. He equated good citizenship with Protestantism and campaigned vigorously against denominational schools and in support of a public system of education that inculcated Canadian values, which for him were those of the British empire. His view of immigrants and assimilation was captured in one of his most controversial books, The foreigner: a tale of Saskatchewan (Toronto, 1909), in which Gordon employed the racial stereotypes of the era. The immigrant characters brought what he called “Old World” customs and habits to the New World, which often broke out in bitter crusades for revenge and outbursts of violence. The plot revolves around an impoverished Ukrainian family, a rapacious Jewish landlord, and a corrupt Roman Catholic priest. Redemption comes only through embracing the Protestant faith. One critic argued, in the 6 Jan. 1910 edition of the Manitoba Free Press, that the author wrote from a “prejudiced Anglo-Saxon perspective,” while another in the Montreal Weekly Star on 10 March pointed out that “the Galicians as a race are shamefully libeled,” and the novel is “full of mean and contemptible untruths about priests of the Catholic church, her doctrines, and practices.”

Gordon, in addition to dealing with these activities, was always in high demand to preach at Sunday services. A former classmate from Knox College, the Reverend Robert Haddow, after viewing him in the pulpit, described him as “tall, slender and well set-up, with a pale intellectual face. His voice as he speaks, is soft and clear. He reads with expression and his prayers are reverent and intimate.… He thinks clearly and … expresses himself in chaste and elegant language.” His piercing grey eyes conveyed a sense of his deep and abiding faith. He could move the most hardened worker to an outburst of personal conviction.

At the advanced age of 54 Gordon, who had been chaplain to the Winnipeg-based 79th Regiment (Cameron Highlanders of Canada), volunteered for service when World War I erupted. The Manitoba Free Press of 11 Aug. 1914 recorded that, on the first Sunday after Canada joined the war, he encouraged his congregation to be “resolved upon sacrifice to the limit.” Canada’s involvement, he insisted, was not merely a matter of fulfilling its duty within the empire, but also a matter of fighting as a nation for the principles of democracy, justice, and honour. Gordon recognized at the outset that the war would likely be costly and not easily won. This recognition of the heavy toll that the war would take made Gordon’s call for national sacrifice uncompromising. He had no tolerance for any deviation from a total commitment to the war effort. For Gordon, there was a deeply personal reason for his decision to serve overseas as a chaplain. Since he had so vigorously advocated that the young men of his congregation volunteer and enlist, he felt an overwhelming sense of responsibility for their well-being, which he could fulfil only by accompanying them overseas. The 79th Regiment, which had over 300 members from St Stephen’s parish in its ranks, became part of the 43rd Infantry Battalion in the 3rd Canadian Division. Gordon, an honorary captain in the Canadian Chaplain Service [see John Macpherson Almond], was promoted honorary major on 12 Nov. 1915 and senior chaplain at Shorncliffe, England, the most important Canadian training camp. He soon resigned the position to join his men at the battlefront as senior chaplain of the 3rd Division. He was present during the prolonged and bloody conflict of the Somme in the summer and autumn of 1916. Tragically, most of the men from his battalion were killed while attempting to take the Regina Trench. Caught on barbed wire, they became easy targets for enemy fire. Reminiscing to a correspondent in the 1920s, Gordon described the carnage in stark terms: “On October 8th we went in with 504 men and next morning reported only 65.”

Shortly after the disaster, Gordon was granted leave to return to Canada to help settle the estate of his regiment’s lieutenant-colonel, Robert McDonell Thomson, his close friend, financial adviser, and parishioner, who had died during the battle. Gordon discovered that Thomson’s negligent handling of his substantial royalty income had left him in financial crisis. When he departed for the front, his wealth was estimated at between $750,000 and $1,000,000; he was now almost $100,000 in debt. Perhaps for the sake of his family (Thomson had married the widow of Gordon’s brother) he would seldom talk about the matter and would only briefly allude to it in his autobiography.

Gordon continued to work for the war effort. Like others who had witnessed the casualties at the front, he was concerned about recruitment. For him the supreme sacrifice made by soldiers would become futile if Canadians at home failed to support them. He spoke out vigorously in favour of conscription. At the request of Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden he toured the country to promote the war effort. He was critical of the negative attitude of the people of Quebec towards the war, but attributed it to “narrow-minded bigots, … and self-seeking party politicians,” who had “distorted and destroyed their nobler emotions and loftier principles.” Early in 1917 he began a lecture tour of the United States to explain the Allied position and the need for American participation. He wrote a poem, “The falling torch,” which drew on the imagery in the last stanza of Major John McCrae*’s poem “In Flanders fields” to emphasize the need for sacrifice. His wartime novel, The major (1917), was essentially a means of recruiting soldiers: the protagonist abandons the pacifist tenets of his Quaker faith in favour of serving his country. Discharged in 1919 after the war’s end, Gordon wrote The sky pilot in no man’s land, published that year. Although this Connor novel exposed some of the horrors of the battlefield, the underlying message was that the casualties of war should be considered Christ-like, since the men had given up their lives for others.

The aftermath of the war was one of the busiest periods of Gordon’s career. He was absent during most of the Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowski*] of 1919 because he was participating in the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, held in Toronto. For Gordon, the strike was symptomatic of a deeper post-war spiritual malaise. In the Manitoba Free Press of 15 Sept. 1915, he was quoted as remarking to his St Stephen’s congregation that Canada had become “a country torn with strife, seething with uncertainty, where discontented men and women throng the streets.” For peace and civility to be restored in Winnipeg and the rest of Canada, the example of the soldiers’ spirit of sacrifice had to be followed. The problem, according to Gordon, was that the Church was no longer in a position to provide the spiritual healing and leadership that was required.

In 1920 the Manitoba government of Tobias Crawford Norris appointed him chairman of the Joint Council of Industry, which was established after the strike. Before the war, Gordon had served as a conciliator under the terms of the federal Industrial Disputes Investigation Act (1907) for two labour disputes in Winnipeg in 1909 and during the miners’ strike in the coalfields of Alberta [see Frank Henry Sherman*] and British Columbia in 1911. He believed in the right of workers to organize. Like the future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*, he was of the opinion that there were common interests between capital, labour, and the wider public, so he did not take a strictly pro-labour stand in these conflicts. As did others who preached the Social Gospel [see James Shaver Woodsworth*], he held that Christ’s life and teaching made it imperative that principles of charity, justice, and brotherhood be intrinsic to all relationships in society. Between 1920 and 1924 he oversaw industrial relations in Manitoba as chair of the Joint Council of Industry, and he was the conciliator in over 100 disputes. In all cases strike action was averted. For Gordon, this amounted to success since he considered industrial peace to be important. His Social-Gospel views as they pertained to labour issues were most fully expressed in his 1921 novel, To him that hath: a novel of the west of today. The maintenance of peace and harmony became the overriding principle of Gordon’s post-war Christian social ethics. He strenuously advocated for world peace; in 1932 he delivered the annual sermon before the League of Nations [see Newton Wesley Rowell*]. Drawing on his experiences in the First World War, he eschewed his previous equation of militarism with a Christian calling.

In 1922 Gordon was appointed moderator of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. He served during the final years of bitter debate within Presbyterianism [see Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon] regarding union with the Methodists [see Samuel Dwight Chown] and Congregationalists. He had been an advocate of union since it was suggested in 1902 by Principal William Patrick of Manitoba College. For Gordon, it was a necessary measure to halt the wasteful duplication of men and resources that undermined efforts to build the Protestant church in the west. Union was also consistent with Gordon’s liberal theology, which rejected dogmatism and sectarianism, and was committed to evangelicalism and social reform that fostered cooperation between denominations. Gordon’s determination to bring about union was so strong that he did everything possible to hinder those opposing it, such as Ephraim Scott. As moderator, he campaigned vigorously for union across the country. At the General Assembly of 1925, in an attempt to drown out the deliberations of the non-concurring Presbyterians who were determined to hold on to their identity, he instructed the organist to play Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus as loudly as possible. After the creation of the United Church of Canada, St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church merged with Broadway Methodist Church and officially became St Stephen’s–Broadway in 1927, but this amalgamation did not displace Gordon since he had turned 65 in 1925 and retired from the ministry.

During his retirement Gordon continued to write fiction. Most notable was a series of historical romances about Canada’s past, which featured Quebec after the conquest, the American revolution, and the War of 1812 as backdrops for his tales of adventure. Other novels, especially those written during the Great Depression, addressed that world crisis from a Christian perspective. Gordon was critical of the greed and lack of Christian morality within the financial and industrial systems.

Gordon was unable to adapt his style to the times and the sales of Connor novels trailed off. His didactic adventure stories and strict morality no longer appealed to a reading audience that sought a more realistic and perhaps less romantic and religious view of life. This change in popular taste did not deter him. More certain than ever that people had lost touch with the Bible and the Saviour, he decided to write a biography of Jesus Christ. He dwelt among us (1936) was his final sermon. In explaining his purpose, he wrote to George Adam Smith, one of his theological mentors: “I have a deep conviction that what the world needs today, more than anything else, is a return in simplicity and faith and loyalty to the heart of Jesus. He is a forgotten man. He has become a Name in a book, a Name in a system of theology, a shadowy Figure in a religious institution, the reality has gone out of Him, we are no longer able to feel the pulse of His Heart, the touch of His Hand.”

Gordon did not define his ministry in terms of his writing. His novels brought him fame and a great deal of money, but in his estimation they were merely part of his mission to spread the Word of God and make the church a visible presence in society. According to him, a minister had to preach a practical gospel and work to effect change. He considered himself a man of action like the heroic muscular Christians in his novels, emulating Christ whose deeds had had such a profound impact. Appropriately, he entitled his memoirs, which he wrote in the final year of his life, Postscript to adventure: the autobiography of Ralph Connor. The book was published posthumously in New York City in 1938 and featured an introduction by his son, John King Gordon.

For his accomplishments in various fields Gordon had received numerous awards. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (1904), and several institutions granted him honorary degrees, including Queen’s College (lld, 1909), the University of Glasgow (dd, 1919), and the University of Manitoba (lld, 1937). In 1935 he was made a cmg.

Despite his fame as Ralph Connor, Gordon believed his calling to be that of a preacher of the gospel of Christ. He never considered himself to be primarily a novelist, and near the end of his life he suggested to a reporter for the Toronto Daily Star (12 Nov. 1936) that his contribution to Canadian culture had been to liberate religion from the prayer meeting and parlour. His novels do not hold a prominent place in the Canadian literary canon. They are considered to be windows into the popular culture of early-20th-century Canada with respect to evangelical religion, social reform, the opening of the west, the myth of the Mountie, and the First World War and its aftermath. While Gordon regarded Canada as an integral part of the British empire, his novels helped define a clear sense of the country, its identity, and its history. As a clergyman of the Social Gospel Gordon was an outspoken, crusading moral reformer, although his dogmatism was tempered by the war. No matter what he was engaged in, he approached life with great passion, conviction, and boundless energy, sometimes to the point of appearing intolerant. But within the confines of his family life, Gordon was fondly remembered by his children as being playful and having a great love for the outdoors, traits that they associated especially with time spent at the family cottage, Birkencraig, on the Lake of the Woods.

Charles William Gordon died in October 1937. He was buried in Kildonan Presbyterian cemetery near Winnipeg, where many of the other founding members of the Presbyterian Church in the west, including John Black*, George Bryce, John Mark King, and his mentor James Robertson, were also interred.

Under the pseudonym Ralph Connor, Charles William Gordon authored the following novels: Black Rock: a tale of the Selkirks (Toronto, 1898); Gwen, an idyll of the canyon (Toronto and New York, 1899); The sky pilot: a tale of the foothills (Toronto, 1899); The man from Glengarry: a tale of the Ottawa (Toronto, 1901); Glengarry school days: a story of early days in Glengarry (Toronto, 1902); The prospector: a tale of the Crow’s Nest Pass (Toronto, 1904); The doctor: a tale of the Rockies (Toronto, 1906); The foreigner: a tale of Saskatchewan (Toronto, 1909); Corporal Cameron of the North West Mounted Police: a tale of the Macleod Trail (Toronto, 1912); The patrol of the Sun Dance Trail (Toronto, 1914); The major (Toronto, 1917); The sky pilot in no man’s land (Toronto, 1919); To him that hath: a novel of the west of today (New York and Toronto, 1921); The Gaspards of Pine Croft: a romance of the Windermere (Toronto, 1923); Treading the winepress (New York and Toronto, 1925); The friendly four, and other stories (New York, 1926); The runner: a romance of the Niagaras (Toronto, 1929); The rock and the river: a romance of Quebec (Toronto, 1931); The arm of gold (Toronto, 1932); The girl from Glengarry (Toronto, 1933); Torches through the bush (Toronto, 1934); The rebel loyalist (Toronto, 1935); The gay crusader (Toronto, 1936); and He dwelt among us (Toronto, 1936). He also wrote a number of booklets as Ralph Connor, including Beyond the marshes: a Manitoba idyll (Winnipeg, 1897); Gwen’s canyon (Toronto, 1898); Michael McGrath, postmaster (Chicago and Toronto, 1900); The Swan Creek blizzard (Toronto, 1901); The angel and the star (Toronto, 1908); The dawn by Galilee: a story of the Christ (Toronto, [1909]); The recall of love (Toronto, [1910]); and Christian hope ([London, 1912]). Under his own name, he published a biography, The life of James Robertson: missionary superintendent in western Canada (Toronto, 1908), and Postscript to adventure: the autobiography of Ralph Connor (New York, 1938). He also published a chapter entitled “The Presbyterian Church and its missions,” in Canada and its provinces: a history of the Canadian people and their institutions …, ed. Adam Shortt and A. G. Doughty (23v., Toronto, 1913–17), 11: 249–300.

The Charles Gordon fonds (mss 56, Pc 76) is located at the Dept. of Arch. and Special Coll., Univ. of Man. Libraries in Winnipeg. Family correspondence is at LAC, R2409-22-1 (C. W. Gordon (Ralph Connor) ser.). Valuable correspondence can also be found in the James Robertson coll. at UCC, F3345. Critical and biographical accounts appear in Daniel Coleman, White civility: the literary project of English Canada (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2006); Christopher Dummitt, “The ‘taint of self’: reflections on Ralph Connor, his fans, and the problem of morality in recent Canadian historiography,” Social Hist. (Ottawa), 46 (2013): 63–90; Clarence Karr, Authors and audiences: popular Canadian fiction in the early twentieth century (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2000); D. [B.] Marshall, “C. W. Gordon, a.k.a. Ralph Connor: clergyman, author, chaplain and moderator,” Touchstone (Winnipeg), 20 (2002), no.1: 41–52; J. L. Thompson and J. H. Thompson, “Ralph Connor and the Canadian identity,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston), 79 (1972): 159–70; and M[ary] Vipond, “Blessed are the peacemakers: the labour question in Canadian Social Gospel fiction,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 10 (1975), no.3: 32–43.

Cite This Article

David B. Marshall, “GORDON, CHARLES WILLIAM (Ralph Connor),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_charles_william_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_charles_william_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David B. Marshall |

| Title of Article: | GORDON, CHARLES WILLIAM (Ralph Connor) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 31, 2025 |