Source: Link

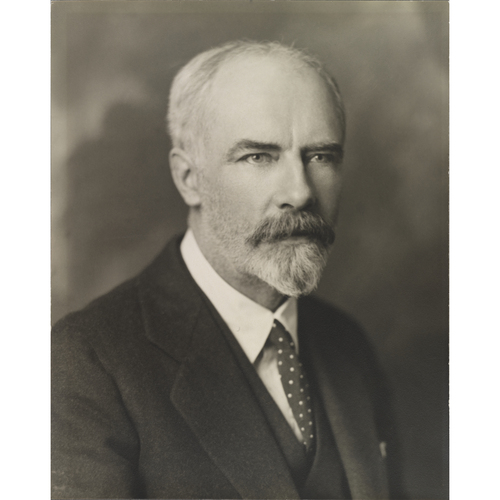

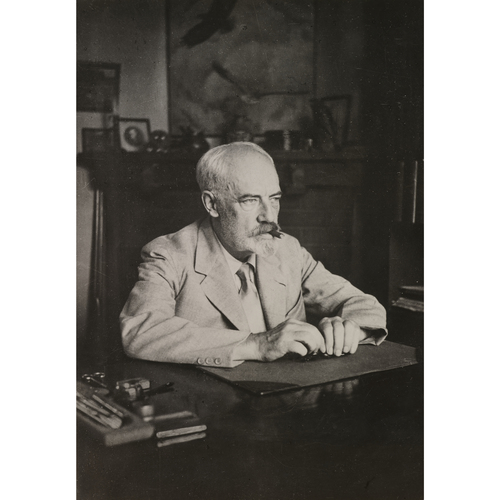

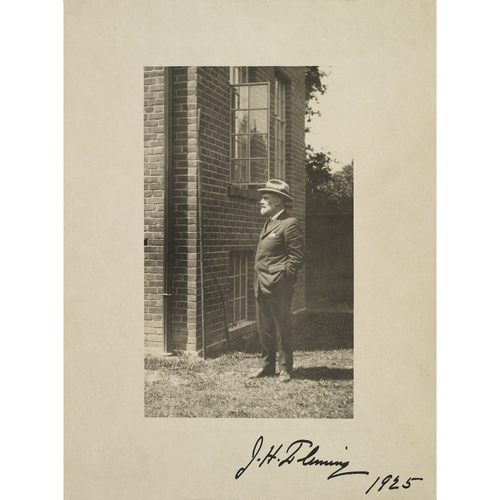

FLEMING, JAMES HENRY, naturalist; b. 5 July 1872 in Toronto, only son of James Fleming, a businessman, and Mary Elizabeth Wade, his second wife; m. first 8 Dec. 1897 Christine Mackay Keefer (d. 1903) in Ottawa, and they had a daughter and a son; m. secondly 14 Oct. 1908 Caroline Toovey (1878–1958) in Aston Sandford, England; d. 2 June 1940 in Toronto.

James Henry Fleming, commonly known as Harry, was born, raised, and lived his entire life in Toronto. His childhood family home was on the southwest corner of Yonge and Elm streets, where his father, a Scottish immigrant and successful seed merchant, had established in 1837 a horticultural operation of two and a half acres on land owned by Jesse Ketchum*. By the time Fleming was born in 1872, the gardens – located on what were then the northern outskirts of a city with a population of less than 10,000 – were not only a prosperous business enterprise but also an oasis along the thoroughfare of Yonge Street. The lush grounds provided a world of exploration for a young boy and it was there that Fleming, constantly accompanied by a Newfoundland dog named Wallace, nurtured his penchant for natural history. His passion for collecting began with his seeking out insects in the gardens and pinning them for display. One of Fleming’s earliest ornithological memories was of purple martins nesting in the birdhouse placed by his parents in the gardens, a birdhouse he would later relocate to the house he purchased in 1892. University of Toronto field trips were often conducted on the property and Fleming was able to tag along behind the students and glean interesting information.

Because of his successful horticultural business, Fleming Sr had become a prominent citizen of the city, serving as a justice of the peace and as an alderman. As for young Harry, the gardens were both an incubator for his natural-history interests and the source of the family wealth that would allow him to pursue his lifelong passion for collecting birds and ornithological literature. When his father died in 1887, he left an estate worth nearly $200,000 to his wife and son, with most of the land passing to Harry on his 25th birthday.

Harry Fleming received his formal education first at the Toronto Model School and then at Upper Canada College, graduating from the latter in 1889. But it was the knowledge he acquired on his own, at his home and in the neighbourhood of his boyhood years, that would determine the course of his adult life. In 1884, at the age of 12, Fleming found a small grass nest of a vesper sparrow replete with four unhatched eggs. He carefully removed the contents from the eggs and added them to his collection, which already contained preserved hummingbirds that he had purchased from millinery suppliers that sold the colourful birds as adornments for the hats of fashionable Toronto socialites. The hummingbirds were available for 10 cents each and, by saving 5 cents of the 15 cents he received each day for lunch, the budding naturalist was able to buy six different specimens over two weeks. He would manage his personal finances in much the same way for the rest of his life.

While in his early teens, Fleming was influenced by two distinctive Victorian institutions. The first was the taxidermy shop of William Cross, located on Queen Street West between Fleming’s home and Upper Canada College. Like others of its kind, it was a vital hub in the local natural-history network. Sportsmen, egg collectors, and wildlife enthusiasts of all kinds would gather there daily to exchange stories, specimens, and ideas, and it was at this establishment that Fleming made the social contacts with like-minded naturalists and collectors that would form the foundation of his ornithological career. One of the most important of these was William Brodie*, who would become a significant mentor following the death of Fleming’s father.

The second Victorian institution that had a major impact on Fleming was the British Museum (Natural History) in London, England. In 1886 he accompanied his father to the United Kingdom where the youth explored the museum’s collection. It made an indelible impression on him and before returning to Canada he informed his father that his goal was to form a representative collection of birds.

In 1888 Fleming began keeping a detailed field journal to describe sightings and collecting results. The journal, which he faithfully maintained for the rest of his life, led to his being admitted to the ornithological subsection of the Canadian Institute in 1889 through a special provision for an associate (junior) membership; his relationship with the institute enabled him to participate in the assembling of records and specimens of Ontario birds. Following a two-year visit to Europe that included a brief enrolment at the Royal School of Mines in London, Fleming returned to Toronto in 1891 and dedicated himself to the full-time pursuit of amateur ornithology.

The following year Fleming purchased a house on Rusholme Road, close to Heydon Villa, home of George Taylor Denison*. Located between Bloor and College streets, the neighbourhood was then surrounded by extensive open lands and wild areas. Fleming earnestly engaged in collecting birds near his home, killing 77 birds of 44 species in May 1892 alone. One of the most notable incidents occurred on the evening of 6 June 1892 when Fleming, though knowing that the species was on the verge of extinction, shot and wounded the last passenger pigeon ever recorded in the Toronto region. This was the only time that Fleming saw a live wild passenger pigeon, and the episode illustrates the overwhelming emphasis on specimen collecting that characterized natural history at the time.

At the end of the 19th century, there was growing antipathy towards collecting – the fledgling Toronto Humane Society was among the institutions and individuals who shared this sentiment – and provincial authorities began to limit the letting of shooting permits. But Fleming saw things differently. Like other naturalists such as Thomas McIlwraith*, while he was dedicated to the protection of species, he defended the value of specimens and what has been described as “shotgun ornithology” for the establishment of research collections and the advancement of science. He wrote in the Toronto Globe in 1897: “The ornithologist who works for the knowledge he gets is the best safeguard the birds can have. He explains to the small boy with the 22-calibre rifle the harm he does; he discourages in every way possible the needless killing of birds, and is himself to be found using the field-glass more often than the gun in the field. What he does kill he wants, and he can make good use of the specimens so procured.”

Fleming visited the Caribbean in 1892–93 and there contracted malaria, which would afflict him for the rest of his life. Afterwards, he represented the province of Ontario at the Columbian exposition in Chicago in 1893 with a display of taxidermy birds, and between 1895 and 1897 he was the curator of the Canadian Institute’s museum collection. There were no other professional opportunities in Toronto, or in Canada for that matter, whereby Fleming could pursue his passion for assembling a representative bird collection, and so he carved his own path to achieve his ambition. In 1894 he had entered into a partnership with a local taxidermist, opened the business in his father’s old florist shop, and used the enterprise as a means to procure specimens and species records. The shop continued in the Victorian tradition represented by William Cross’s establishment and became the nexus for regional natural-history activity. It was in that shop that Fleming befriended Percy Algernon Taverner*, who would become a colleague, lifelong correspondent, and, thanks in part to Fleming’s intervention with John Macoun*, first curator of birds at Ottawa’s Victoria Memorial Museum (renamed the National Museum of Canada in 1927). By the mid 1890s Fleming listed his occupation as “naturalist.”

Fleming was an heir to more than his father’s sizeable estate; he was likewise an heir to the Victorian ideal that lauded the personal betterment of the informed citizen through nature study. Amateur natural history was fashionable and expected of the educated person. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the professionalization of the sciences had achieved only a precarious foothold in the study of birds. Fleming could not have been a professional ornithologist simply because such an occupation did not exist in Canada until later in the 20th century. Furthermore, Canada lacked any formal national natural-history collection until 1927, although the Geological Survey of Canada and the Victoria Memorial Museum held items brought together by men such as George Mercer Dawson*, Robert Bell*, and Macoun.

Fleming returned to Britain in the spring of 1895 to visit the British Museum (Natural History) and while there he cultivated business relationships with many of the world’s most prominent natural-history dealers, noteworthy among whom was Ernst Mayr Hartert, the curator of birds for the world’s largest private natural-history collection, amassed by Lionel Walter Rothschild. In the following years, Fleming would trade for, purchase, or otherwise obtain many rare specimens from Rothschild. He would travel to the London area on 11 more occasions during his lifetime. Fleming also developed strong professional ties and friendships with the leading naturalists and ornithologists at institutions in the United States, including the American Museum of Natural History (New York), the Smithsonian Institution (Washington), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (Philadelphia), the Museum of Comparative Anatomy at Harvard University (Cambridge, Mass.), and the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago).

Fleming became a familiar fixture at the leading ornithological-society meetings in North America and also attended a few significant meetings in Europe. In 1905 he was the only Canadian at the International Ornithological Congress in London, where he presented a scientific paper and met many of the world’s most distinguished ornithologists, whom he described light-heartedly in a letter to his mother: “The congress is frightfully noisy[.] Like the tower of Babel any old language goes here apparently the louder the better.… We have got the most extraordinary collection of freaks possible.… Giraffes and barons and freaks some in cases and some outside.…” In Canada that year, along with Taverner and William Edwin Saunders, Fleming was a founding member of the Great Lakes Ornithological Club (GLOC), which had a particular interest in the bird-rich environs of Point Pelee, Ont. The club’s activities would be instrumental in the rationale for establishing Point Pelee National Park. The GLOC is also recognized for its pioneer efforts in bird banding in Canada. Fleming set the example when, on 24 Sept. 1905, he caught an American robin in his backyard and placed a metal ring with the number “1” on its leg, the first such marking in Canada.

Fleming accumulated most of his collection between 1903 and 1925, purchasing, trading for, or shooting approximately 31,500 birds during this period. These were preserved as study skins and stored in sealed museum cases. His accumulation of Toronto-area birds was remarkably complete and contained specimens that he had obtained from most of the leading naturalists of the day. The stories and information associated with these skins provide an archive of what was then a nascent field of study in Canada. Fleming built an addition to his home in 1904 to house his growing collection and expanded it again in 1925 with a two-storey facility for his birds and library. On his death in 1940, his private museum comprised 32,267 birdskins (the most representative private bird collection in the world at the time), more than 2,000 bound ornithological texts (nearly all of the most significant works published in the English language), 10,000 scientific papers, and some 50 years of ornithological correspondence. The entire collection was given to the Royal Ontario Museum where he had been appointed honorary curator of birds in 1927. Fleming had previously become honorary curator of ornithology for the Victoria Memorial Museum in Ottawa in 1913. The latter title recognized his donation of over 350 mounted birds for public display; his bequest remains a legacy to his enduring labour and his desire to see a world-class ornithological collection in his own country.

Fleming’s collecting complemented a detailed understanding of both historical and contemporary ornithology. He had a voracious appetite for reading and dedicated much of his time to the careful examination of ornithological-journal papers and to narrative histories and biographies of natural-history exploration and explorers. He also stayed current in his field through participation in the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU), the predominant bird-study organization in North America, from 1893 until his death. He was a notable member of that body, being elected to the vice-presidency in 1926 when the AOU met for the first time in Canada, and subsequently to the presidency in 1932. The apogee of Fleming’s career occurred in 1934 when he attended the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) in London. There he celebrated his 62nd birthday by having a photograph taken of himself, as AOU president, with the presidents of the IOC and the British Ornithologists’ Union. His name had become synonymous with an institution, an amalgam of the man and the ornithological archives that he had assembled.

By the end of Fleming’s term as president of the AOU in 1935, ornithology had reached a significant bifurcation. One branch emerged as a professional and specialized science while the other continued along the lines of Victorian amateur natural history. The ornithological journals, led by the AOU’s journal the Auk, were calling for papers of a more scientific and theoretical nature and collecting was being supplanted by field observation. Concomitantly, natural-history organizations that had flourished at the turn of the century were revived and Fleming participated in their work. For example, the Brodie Club (founded as the Toronto Naturalists’ Club in 1921), the Toronto Ornithological Club, and the Toronto Field-Naturalists’ Club were vital organizations in the 1930s and Fleming held honorary, but active, positions in all of them.

A visitor to Fleming’s home on 2 March 1938, Doris Huestis Speirs, wrote that “he belongs to the old school of true Canadian gentlemen, with closely clipped white beard and hair, like my grandfather’s. He has perfect manners … [and] a great and driving love of birds.” Just over two years later, Fleming died of “hardening of the arteries of the brain” and was buried in the Toronto Necropolis; the inscription on his gravestone describes him simply as “Ornithologist.”

Fleming pursued his career during a brief period when it was possible for an amateur naturalist to ascend to the pinnacle of international ornithology as it evolved from a descriptive, collection-based science to one that was more theoretical and behaviour-based. He recognized the benefits that could result from both professional specialization and amateur natural history and valued the activities of each. Acknowledged as the dean of Canadian ornithology, Fleming had a distinguished career as an ornithologist and was recognized internationally for his comprehensive private collection and knowledge of systematic ornithology. His accomplishment in collecting had no Canadian precedent, nor could it be repeated by a private individual. He can be counted among a small number of private natural-history collectors who made such contributions around the world.

James Henry Fleming left his entire collection of birds, books, and papers to the Royal Ont. Museum in Toronto. The J. H. Fleming fonds (SC29) at the ROM, Libraries and Arch., is a tour de force of ornithological activity during the period 1891–1940; it contains manuscripts, photographs, notes, journals, and scrapbooks totalling over 10,000 items, as well as approximately 8,500 letters to and from more than 725 individuals and agencies. Also in this fonds is “The Fleming memorial papers,” a collection of personal reminiscences and biographical details produced by the Brodie Club in 1940.

J. H. Fleming published papers in most of the leading ornithological journals of his time. A full bibliography is provided in L. L. Snyder, “In memoriam: James Henry Fleming,” Auk: a Quarterly Journal of Ornithology (New York), 58 (1941): 1–12 (pp.10–12). He also wrote “Protecting our birds,” Globe, 15 May 1897: 2.

Cyrus Leger, “Master ornithologist,” Toronto Star Weekly, 26 Nov. 1932: 4. Biographical dictionary of American and Canadian naturalists and environmentalists, ed. K. B. Sterling et al. (Westport, Conn., 1997), 271–73. R. D. James, “James Henry Fleming (1872–1940),” in Ornithology in Ontario, ed. M. K. McNicholl and J. L. Cranmer-Byng (Whitby, Ont., 1994), 171–74. M. S. Quinn, Finding aid to SC29: the J. H. Fleming collection, Royal Ontario Museum, Library and Archives (Toronto, 1993; copy at the ROM, Libraries and Arch.); “The natural history of a collector: J. H. Fleming (1872–1940), naturalists, ornithologists and birds” (phd thesis, York Univ., Toronto, 1995). P. A. Taverner, “James Henry Fleming, 1872–1940: an appreciation,” Canadian Field-Naturalist (Ottawa), 55 (1941): 63–64.

Cite This Article

Michael S. Quinn, “FLEMING, JAMES HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fleming_james_henry_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fleming_james_henry_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael S. Quinn |

| Title of Article: | FLEMING, JAMES HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |