Source: Link

ROSS, WILLIAM GILLIES, businessman, office holder, philanthropist, and sportsman; b. 6 Aug. 1863 in Montreal, fourth of the eight children of Philip Simpson Ross* and Christina Chalmers Dansken; brother of Philip Dansken Ross*; m. 18 Dec. 1888 Ida Elizabeth Millard Babcock in Montreal, and they had three sons and two daughters; d. there 15 April 1929.

On graduating from the High School of Montreal, William Gillies Ross followed his father into accountancy and in 1883 he became a partner in Philip S. Ross, later P. S. Ross and Sons. After several years of auditing, he left the firm to become involved in administration, initially with the Windsor Hotel Company of Montreal, in which he rose from secretary and treasurer to general manager by 1890. Then a revolution in urban transit systems in North America attracted his attention, as electricity began to replace horses. In association with railway engineer James Ross* (no relation) he became involved in the organization and electrification of street railways in Montreal, Saint John, Toronto, Winnipeg, and other cities from about 1892 to 1896. His experience led to his appointment as controller of the Montreal Street Railway Company in 1896. During a strike in May 1903, believing that the workers had no justifiable grievance and that the trams should be kept running, he rode many of them (with revolver in hand, according to one story), helped to preserve order, and gave regular press conferences to report on the status of the various lines. His efforts were applauded by the company, the press, and the public. The Gazette remarked on his “nerve, aggressiveness and force,” and when he was promoted to managing director several months later he was described by the Montreal Daily Herald as “a man who does.” He was by no means anti-labour, however; in 1904 he founded the Montreal Street Railway Mutual Benefit Association.

Described by a contemporary as a “man of indefatigable energy, tremendous ability and keen imaginative vision,” Ross demonstrated these qualities during seven years as managing director of the Montreal Street Railway. In addition to planning and overseeing the growth of the system and the amalgamation of other street railways on the island of Montreal, he had to cope with the challenge of operating streetcars in winter and the problem of overcrowded cars during rush hours, when conductors had difficulty circulating to collect fares. Ross and his associate Duncan A. L. McDonald designed the pay-as-you-enter streetcar, on which a stationary conductor collected fares as passengers boarded by a single entrance at the rear. The first PAYE car in North America was introduced in Montreal in 1905. Simple as the idea was, it met with opposition, and even derision, in some quarters. Yet when the Canadian concept was introduced to New York and Chicago in 1908 it was called “the greatest single innovation of recent years for the comfort and safety of street railway passengers in the United States.” Ross’s reputation for skilful and innovative management had already launched him into a wider world of public transit interests. He had been elected president of the Canadian Street Railway Association and of the Street Railway Accountants’ Association of America in 1904. Six years later he became the first Canadian to serve as vice-president of the American Street Railway Association.

Ross’s growing reputation for organizational ability and business acumen brought him into association with a variety of enterprises. During his business career he served either as president, vice-president, director, managing director, or general manager of 19 firms, including many related to transportation (such as Montreal Tramways Company and Pay-As-You-Enter Car Corporation), several electric companies (Beauharnois Electric Company, Canadian General Electric Company), others involved in resource development (Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited, Asbestos Corporation of Canada), and a variety of financial and land companies.

One writer observed that “his mind was many-sided and seemingly capable of grappling with many problems simultaneously.” Although he presented a calm and cheerful exterior, the diversity and intensity of the work took a toll. When a syndicate headed by Edmund Arthur Robert* secured control of the Montreal Street Railway Company in 1910 with policies that differed fundamentally from his own, he resigned, “to take a well-earned rest” and spend the winter of 1910–11 in Europe. The public clamoured for his return. In 1913 Ross, described by the Daily Telegraph as “the one man in Montreal who knows how to run a tramway,” accepted a position on the board of the company, now Montreal Tramways.

In 1912 Ross had been named president of the Montreal Harbour Commission, the federally appointed board responsible for the port. It was a heaven-sent opportunity for a man who loved boating and was experienced in transportation. Montreal accommodated both river and ocean ships and, as a place of trans-shipment between the two, it possessed extensive storage facilities, but various factors hindered its development. With his characteristic energy, he set about improving the efficiency of the port, building on the work of predecessors and seeking new ideas. During a three-month trip in 1914 Ross and two colleagues visited 25 ports in Europe and on subsequent trips they toured ports in North America. In Montreal dockside rail services were improved, new warehouses were built, and grain storage facilities were enlarged. By 1918 a contemporary professional journal declared that within a decade Montreal had progressed from “a mere stopping place for ships” to “the front rank of ocean ports.” It possessed a buoyed and lighted channel more than 30 feet deep extending 1,000 miles to the sea; it had North America’s best system of connecting railways to docks; it stood second to New York among Atlantic seaboard ports in ocean traffic and value of trade; it was the largest grain shipping seaport in the world with the world’s largest seaport grain elevator; and it was said to be “the most efficient port in America.”

Ross did not hesitate to publicize Montreal’s progress and extol its advantages. As president of the commission, he inevitably received much credit for achievements to which many others had contributed in significant ways [see Sir John Kennedy]. Nonetheless, his organizational abilities were widely recognized. He was elected president of the American Association of Port Authorities in 1916 and re-elected the following year.

In 1911, while Ross was helping to transform Montreal into one of the “foremost ocean ports in the world,” friends persuaded him to accept the presidency of the struggling Amalgamated Asbestos Corporation. Despite the pessimistic predictions of many, the enterprise, reorganized the following year as the Asbestos Corporation of Canada, was soon in a strong financial position, with profits rising steadily. Its recovery during more than a decade under his management was called by the Gazette “one of the most romantic developments in Canadian mining and industrial history.”

Appointed director of naval recruiting for the province of Quebec in 1916, Ross addressed rallies and organized many events in support of the war effort. Serving as president of the Canadian branch of the British Sailors’ Relief Fund, he personally donated $10,000 – an amount equal to the contribution of the most generous bank – to get its fund-raising drive started. The money collected – nearly $3,000,000 – was sent to England to benefit navy and merchant-marine sailors and their families. In appreciation of his efforts, the British Navy League made him an honorary vice-president and awarded him its special service decoration. Ross was one of the founders and the first dominion president (1917–19) of the Navy League of Canada. He was also a fund-raiser for the Canadian Patriotic Fund and the Harry Lauder Million Pound Fund for disabled Scottish veterans. In addition, he made many small but generous gestures, such as sending apples to a visiting warship, taking wounded soldiers cruising on his yacht, and dispatching gifts to troops overseas. A president of the St Andrews Society in 1921–22 and a life governor of the Montreal General Hospital, he donated money and property to McGill University and to various institutions and charitable organizations.

Some of the moral principles that guided Ross’s life are set out in a small pamphlet which he published and gave to his sons on their 21st birthdays. “The basis of success and happiness in life is character and truthfulness – never depart from them,” he wrote. “Take off your coat and make dust in the world,” he counselled. He practised what he preached, raising plenty of dust in street railway operation, port management, asbestos mining, wartime activities, amateur sport, charitable causes, and community affairs. He belonged to dozens of clubs – some social, others related to sports – in Montreal, Ottawa, Quebec, the Eastern Townships, London, and New York. Business affairs had brought Ross into frequent contact with politicians, but he took aim at political office only once, in 1921, when the Conservative candidate in the federal riding of St Antoine withdrew unexpectedly. He was defeated at the polls.

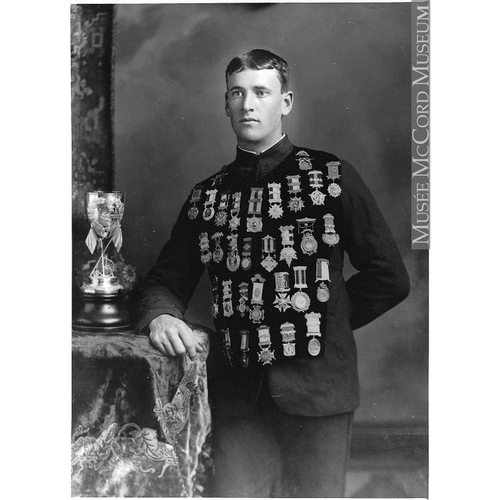

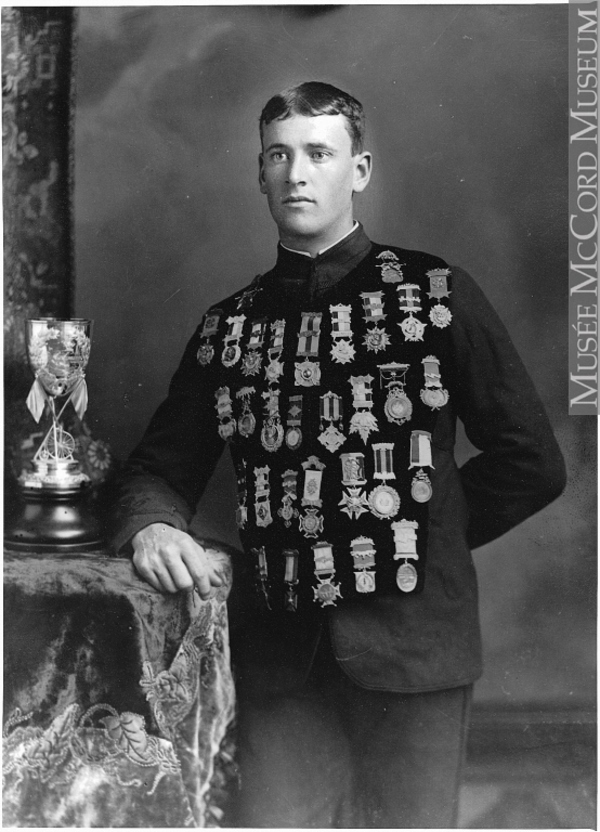

No account of Ross’s life would be complete without mentioning his involvement in sport. At age 18 he had joined the Montreal Bicycle Club. He quickly achieved outstanding success in local competitions. When the Canadian Wheelmen’s Association held one- and five-mile races in London, Ont., in 1883 for the national championships, Ross won both events. That year he competed in 16 races in Canada and lost only one – a handicap race in which he had the fastest time. At the major American meet in Springfield, Mass., he came third in two events and fourth in two others, at distances ranging from a half-mile to ten miles. When he unexpectedly announced his retirement from competition a year later, a Montreal newspaper regretted the loss of “one of the fastest men in America.”

As a young man, Ross had also played for the Britannia Football Club, competed in canoeing, skating, and snowshoe races, and participated in ice-boating, lacrosse, and other recreational activities. Although professional life and a growing family made increasing demands upon his time after 1890, he continued to be active, both as a competitor and as an administrator. He firmly believed in the character-building role of amateur sport and worked to stimulate participation, improve facilities, and expand organizations. He was one of the founders of the Canadian Amateur Skating Association in 1886 and served as its president from 1893 to 1895, in 1905, and perhaps in other years. In 1894 the association organized what he called “the greatest skating meeting ever held in the world” in Montreal. In 1908 he served on the Central Olympic Committee.

In sports as in life, Ross was a determined competitor, a man who, according to the Herald, “always does what he has to do with all the power that is in him.” Winning was not the only goal, however. Sports brought him in touch with others on a friendly and informal basis. During two decades after 1907 he and his four brothers competed annually in curling and golf, and occasionally in hockey, against five Hodgson brothers. Canada’s leading golf magazine considered that there was “nothing more interesting in the realm of amateur sport than these inter-family matches.” After the formation of the Canadian Senior Golf Association in 1918, Ross regularly competed in its annual championships, played on Canadian seniors’ teams against the United States, and served as a governor of the association. In 1925 he won the seniors’ individual championship of the two countries.

William Gillies Ross died in 1929 after an operation. The Montreal Daily Star praised “his broad sympathies, his youthful enthusiasms, his quiet manner, and his habitual cordiality.”

William Gillies Ross is the author of Father’s advice (n.p., n.d.), a privately published pamphlet, and “Development of street railways in Canada,” Street Railway Rev. (Chicago), 11 (1901), no.1: 30–31. He also wrote “Montreal port organization,” Freight Handling and Terminal Engineering (New York), but nothing more is known about this article (a copy is in the possession of the author).

ANQ-M, CE601-S115, 18 déc. 1888; S120, 6 août 1863. Private arch., W. G. Ross (North Hatley, Que.), 16 scrapbooks of newspaper clippings, articles, and speeches given by the subject; reminiscences. Daily Telegraph (Montreal), 5 Aug. 1913. Gazette (Montreal), 16 April 1929. Globe, 16 April 1929. Montreal Daily Herald, 11 Dec. 1903. Montreal Daily Star, 15–16 April 1929. Martin Burrell, “The late Mr. W. G. Ross,” Canadian Golfer ([Brantford, Ont.]), 15 (1929–30): 8–10. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). “Eighth annual seniors’ tournament,” Canadian Golfer, 11 (1925–26): 464–77. “The passing of Mr. W. G. Ross,” Canadian Golfer, 14 (1928–29): 941. Prominent people of the province of Quebec, 1923–24 (Montreal, n.d.). The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. W. [C. H.] Wood et al., (5v., Toronto, 1931–32).

Cite This Article

W. Gillies Ross, “ROSS, WILLIAM GILLIES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_william_gillies_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_william_gillies_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. Gillies Ross |

| Title of Article: | ROSS, WILLIAM GILLIES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |