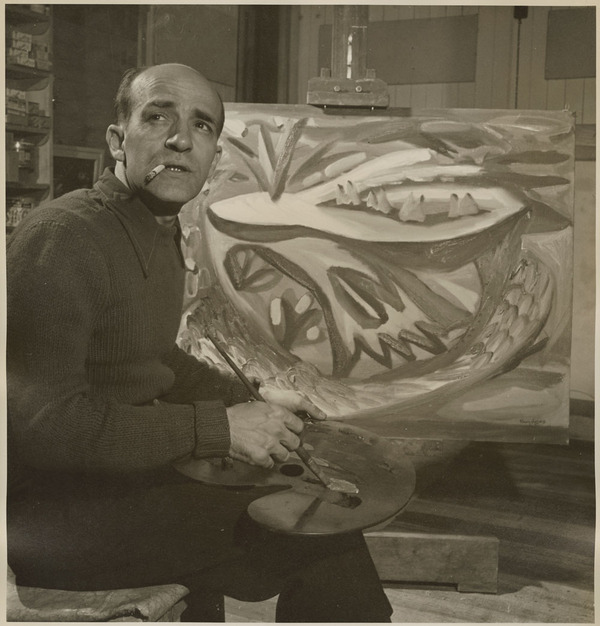

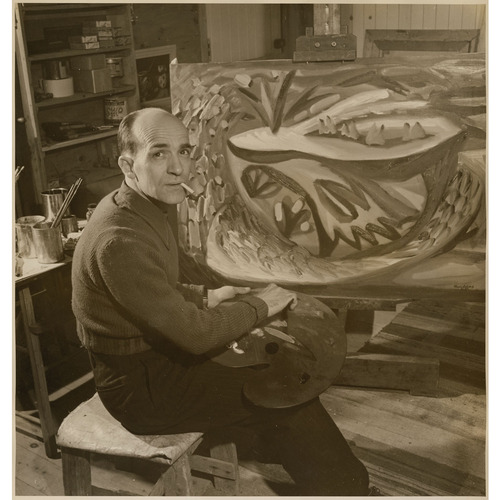

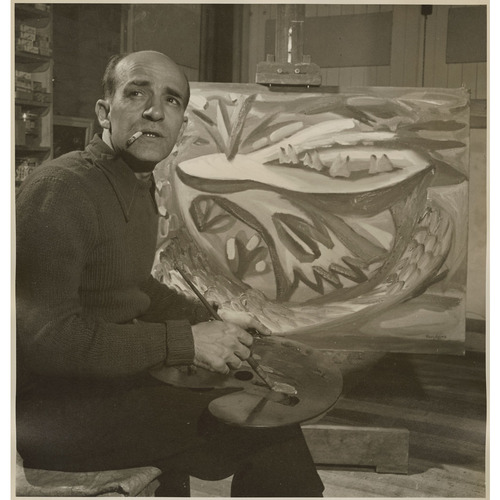

BORDUAS, PAUL-ÉMILE (baptized Paul-Émile-Charles), painter; b. 1 Nov. 1905 in Saint-Hilaire (Mont-Saint-Hilaire), Que., son of Magloire Borduas, a carrier, and Éva Perreault; m. 11 June 1935 at Granby, Que., Gabrielle Goyette, and they had one son and two daughters; d. 22 Feb. 1960 in Paris.

As leader of the Groupe Automatiste and principal author of the manifesto entitled Refus global, Paul-Émile Borduas had a profound influence on the development of the arts and of thought, both in the province of Quebec and in Canada. The fourth child in a family of seven, he first attended the primary school in his native village, and then was given private instruction between 1912 and 1921. In 1922 he had the good fortune to meet the painter Ozias Leduc, who lived on the Montée des Trente in Saint-Hilaire. Leduc took him on as an apprentice in some of his projects to decorate churches, notably the Pauline chapel of Saint-Michel cathedral in the diocese of Sherbrooke, the chapel of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Halifax, and the baptistry of Notre-Dame church in Montreal. The next year Leduc urged his young pupil to enrol in the School of Fine Arts of Montreal, which had recently opened.

By 1925 Emmanuel Fougerat, the school’s first director, had been replaced by Charles Maillard*, who, along with Robert Mahias and Edmond Dyonnet, were Borduas’s teachers. Borduas completed his studies in 1927, graduating with a “first diploma.” Five years later he would be awarded the teaching diploma that qualified him to give drawing lessons in schools. Apparently he did not much enjoy the years he spent at the School of Fine Arts; the kind of training he had received from his first mentor (whom he referred to respectfully as Monsieur Leduc) was more to his liking. Moreover, he quarrelled with Maillard, a painter in the academic tradition, who taught his students to value regionalism and to despise modern art.

After a brief spell as a drawing master in Montreal primary schools – a period that came to an end when Maillard had one of Borduas’s colleagues appointed to a position for which Borduas had himself already been taken on – the young artist went to Paris to complete his training. Through the generous support of Abbé Olivier Maurault*, a friend of Leduc and at that time the curé of the parish of Notre-Dame in Montreal, he was to remain in Paris from the end of 1928 until 1930. He enrolled in the Ateliers d’Art Sacré, which was then under the direction of Maurice Denis and Georges Desvallières. During his stay in Paris, Borduas kept a diary in which he made notes about the courses he took, visits to exhibitions (Pascin, Renoir, Picasso), and his travels in France. His entries give the impression that he found working in the field with Pierre Dubois more congenial than the Ateliers d’Art Sacré. Dubois invited Borduas to go with him to the department of Meuse, where he had church decoration projects at Rambucourt and Xivray-et-Marvoisin. Borduas was only too happy to leave behind the somewhat stuffy atmosphere of Denis’s studio and join the team led by Dubois. Thereby Borduas made the acquaintance of Marie-Alain Couturier, a Dominican priest whom he would meet again in Canada. Couturier would become the editor of the Paris review L’Art sacré, and advocate a rapprochement between the Roman Catholic church and modern artists (notably Le Corbusier, Henri Matisse, and Fernand Léger). This initial contact with Europe, in his youth, was crucial for Borduas. He discovered the École de Paris and was especially excited by the work of Pascin and Renoir. However, unlike his fellow painter Alfred Pellan*, who would spend 14 years in France, he had no contact at that time with the avant-guarde Cubist and Surrealist movements.

When he returned to Canada in June 1930, Borduas expected to follow in the footsteps of his first mentor as a church decorator, a career for which he felt himself well trained. In the autumn of that year Leduc took him on as an associate to decorate the church of the parish of Saints-Anges in Lachine. Thereafter, Borduas tried to make his way as an independent decorator. But his efforts to obtain commissions in his own name for various Montreal churches, including Saint-Denis, Saint-Jean-de-la-Croix, and Saint-Vincent-Ferrier, proved unsuccessful. The depressed economy and the fact that he was still relatively unknown might account for these set-backs. His only commission was a stations of the cross – incidentally quite similar to one painted by Leduc for the church at Saint-Hilaire – that was purchased by the church of Saint-Michel in the parish of Rougemont. Borduas would remain rather bitter about these disappointments and dated his alienation from the Christian faith from this period. As there was virtually no other alternative, he fell back on teaching as a drawing master at the Collège André-Grasset and in schools for the Montreal Catholic School Commission. An extremely heavy teaching load prevented him from doing much work of his own. Moreover, dissatisfied with a number of his paintings, he destroyed many of the canvases or painted over them.

On 11 June 1935 Borduas married Gabrielle Goyette, the daughter of a Granby doctor, with whom he would have three children: Janine, Renée, and Paul. Two years later he was finally appointed professor of drawing and decoration at the École du Meuble in Montreal, at an annual salary of $1,200, replacing Jean-Paul Lemieux*, who had left to teach at the École des Beaux-Arts de Québec. This school, then under the direction of Jean-Marie Gauvreau*, would prove a stimulating environment for Borduas because of the presence of architect Marcel Parizeau and art historian Maurice Gagnon, as well as of the young people who were to be his students. He was also delighted to meet Father Couturier again. The latter had come to North America to preach in Lent for the French parish in New York, but as a result of World War II he had been obliged to prolong his stay; Couturier visited Montreal, and even gave some lectures at the École du Meuble.

A turning point in Borduas’s career was his discovery of Surrealism and, more particularly, in 1938, of a text by André Breton entitled “Le château étoilé.” The article, which was eventually published as chapter five of Breton’s L’amour fou (Paris, 1937), had originally appeared in the 15 June 1936 issue of Minotaure, a journal that Borduas found in the library of the École du Meuble. In this piece, Breton quotes the famous advice of Leonardo da Vinci, who had urged his pupils to look for a long time at an old wall until they saw, emerging in its cracks and stains, patterns they only had to “copy” to make original pictures; Breton found in this approach a way of resolving the opposition between the objective and the subjective, but at a higher level. From Leonardo’s suggestion, Borduas concluded that the painting’s support, whether paper or canvas, could be regarded as a kind of paranoiac screen, on which images from the artist’s unconscious might be projected. By drawing random patterns on this screen without preconceived ideas – and in that sense, “automatically” – Borduas was, as it were, reconstituting Leonardo’s old wall. All that remained to be done was to distinguish formal patterns, make them more precise, and add colour and shade to create an effect of volume.

Borduas applied this process in particular to a series of gouaches he painted in 1942. But, by his own account, his earliest experiment in automatism was Abstraction verte, a small canvas painted spontaneously and directly in oils in 1941, which was reminiscent of his still lifes of the same year. On the initiative of Father Wilfrid Corbeil*, who was always very open-minded with regard to Canadian modern art, the painting was shown for the first time in the parlours of the Séminaire de Joliette from 11 to 14 Jan. 1942.

That year, from 25 April to 2 May, Borduas exhibited 45 gouaches (described as “surrealist works”) in the Salle de l’Ermitage in Montreal. The show was a resounding success financially. It was also received favourably by critics Marcel Parizeau, Robert Élie*, and Jean-Charles Doyon. The gouaches showed the influence of Alfred Pellan, who, since his return to Canada in 1940, had held a number of shows in Quebec City and Montreal, exhibiting the work he had done in Paris. In 1943 Borduas attempted to achieve in oil the effects he had obtained in his gouaches, although he made important changes. Instead of a dichotomy between drawing and colour, he introduced a tension between objects in the foreground and the infinitely receding background in front of which they were suspended, as in Viol aux confins de la matière. And whereas the gouaches, in compositional terms, had faithfully followed portrait or still life traditions, the new work, shown at the Dominion Gallery in Montreal from 2 to 13 Oct. 1943, was dominated by landscapes, which were better suited to evoking images from deep within the unconscious. However, this exhibition was not greeted by collectors with the same enthusiasm as the one presented the previous year.

In this period Borduas gradually began to dissociate himself from his contemporaries, and to draw closer to artists of the younger generation, whether his own students at the École du Meuble (Jean-Paul Riopelle*, Marcel Barbeau, Guy Viau, Charles Daudelin*, Roger Fauteux) or their friends at the School of Fine Arts of Montreal (Fernand Leduc, Pierre Gauvreau*, Françoise Sullivan) and the Collège Notre-Dame (Jean-Paul Mousseau*, Claude Vermette). This circle included several members of the Groupe Automatiste, which was led by Borduas and can be dated back to 1941, when he first began to invite his students and their friends to his studio on Rue de Mentana.

In 1946 and 1947 Borduas and the Groupe Automatiste held exhibitions in a series of makeshift galleries: at 1257 Rue Amherst (Atateken) in Montreal (20-29 April 1946); at the house of Mme Julienne Gauvreau, the mother of Pierre and Claude*, 75 Rue Sherbrooke Ouest in Montreal (15 Feb.–1 March 1947); and in the small Galerie du Luxembourg in Paris (20 June–13 July 1947). Sous le vent de l’île, which was acquired in 1953 by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, was shown in the second of these exhibitions. Painted in 1947, the work represents a continent (rather than an island), above which various fragmented objects – for some critics, a group of indigenous people adorned with feathers – twirl in space. While the background is painted with broad brush strokes, the fragments are done with a palette-knife, which separates them from the background more effectively.

The activity of Borduas as an Automatiste culminated at the Librairie Tranquille in Montreal on 9 Aug. 1948 with the launching of a collection of texts entitled Refus global. The collection included some dramatic pieces by Claude Gauvreau, a lecture by Françoise Sullivan, an article by Bruno Cormier*, and a proclamation by Fernand Leduc, but the principal articles, including the manifesto of the same name, were written by Borduas himself. In the manifesto, which was countersigned by 15 members of the Groupe Automatiste, he denounced the old ideology of preservation, according to which Quebec identity lay in its attachment to Catholicism, to the French language, and to certain rural customs. “To hell with the holy water sprinkler and the tuque!” Borduas thundered in the middle of the manifesto, which called for opening up Quebec culture to the liveliest manifestations of universal thought. “Bludgeoning the present and the future to death with the past is finished!”

The manifesto caused an uproar in the press; some 100 articles, almost all of them negative, came out immediately after it was launched. Its open attacks against Catholicism and the right-wing nationalism symbolized by the Union Nationale cost Borduas his job at the École du Meuble. The painter would always regard his dismissal as a grave injustice, since it was the result of an “extra-curricular” activity and there had been no complaints about his teaching. Several members of the Groupe Automatiste, in particular Pierre and Claude Gauvreau, defended Borduas in the press, but their efforts were in vain. Henceforth, he would have to live by his painting alone. In 1949 he recalled the incident in an autobiographical pamphlet entitled Projections libérantes, in which he wrote: “At last free to paint!” But in reality, his dismissal from the school made things difficult for his family; in October 1951 his wife and children left him, which crushed him. In 1952 he sold his house on the banks of the Richelieu river in Saint-Hilaire to Dr Alphonse Campeau, who took great care of it as long as he lived; it still stands at the beginning of the 21st century.

Disheartened by the oppressive climate in his native province, Borduas thought about going into exile and wanted to move to New York. However, McCarthyism was then at its height in the United States, and the American immigration authorities made things hard for him because he had once been interviewed by Gilles Hénault*. (The interview had appeared in the 1 Feb. 1947 issue of the Montreal communist periodical, Combat.) At that time, a few members of the Groupe Automatiste, including Claude Gauvreau and Jean-Paul Mousseau, had made overtures to the communist Labor-Progressive Party, but their anarchism was ill-suited to the party’s revolutionary discipline, and there was no agreement about the kind of art that could reach the people. Like the Surrealists in France, the Quebec Automatistes were seen primarily as rebels, rather than true revolutionaries. In any case, Refus global has a paragraph entitled “Règlement final des comptes” that marks the Groupe Automatiste’s definitive break with Canadian communism.

Borduas won his case against the Federal Bureau of Investigation and was finally able to move to the United States, initially to Provincetown, Mass., where he spent the summer of 1953 painting at the seaside. He may have met Hans Hofmann at this time, since the German painter gave summer courses in this Cape Cod town, where there was an artists’ colony. In the fall Borduas settled in New York, and he remained there until September 1955. With the support of several Quebec collectors (notably Gérard Lortie) and two New York galleries (the Passedoit Gallery and the Martha Jackson Gallery), he was able to rent a large studio in Greenwich Village. This period was extremely important for the development of his art and career. The title he gave to a canvas painted in 1953, Les signes s’envolent, seems to convey what was going on in his painting, as objects disintegrate (thus “signs” disappear) and the background moves closer to the surface of the painting. From then on, Borduas used only a palette-knife to apply the paint, a technique that gave greater materiality to his work. His first New York exhibition was held at the Passedoit Gallery from 5 to 23 Jan. 1954, and attracted favourable notices. On 6 February Rodolphe de Repentigny, a critic who had come to New York for the occasion, reported in the Montreal paper L’Autorité du peuple that the American painter Robert Motherwell, who was present at the vernissage, had exclaimed: “He’s the Courbet of the 20th century!” However, the Passedoit, which, prior to Borduas, had never exhibited non-figurative painting, was not a very prestigious gallery. Fortunately, his work would be taken up by the Martha Jackson Gallery in exhibitions organized after he had left North America (18 March–6 April 1957 and 24 March–18 April 1959). While in New York, Borduas had realized that, although he could claim to have been inspired by Surrealism, especially its concept of an art originating in the unconscious, the abstract expressionism practised by Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, or Mark Rothko – artists whom he could meet at the Cedar Bar – was going much further in this direction than the automatism of the Montreal group in the period when he was their leader.

Hoping to receive wider recognition in France than in the United States, Borduas set sail on the Liberty on 21 Sept. 1955 with his daughter Janine. Riopelle helped him find an apartment on Rue Rousselet in Paris. Subsequently, the two men saw little of each other. In the five years remaining to him, Borduas would not find in Paris the success he had hoped for. Plans to meet the famous art critic Michel Tapié de Ceyléran did not materialize. None of the avant-guarde movements in the French capital, such as the informal art of Georges Mathieu, Jean Dubuffet’s new figuration, or the “new realities” of Yves Klein, were really to his taste. Admittedly, he had exhibitions in several important European galleries, such as the Arthur Tooth and Sons Gallery in London from 8 Oct. to 2 Nov. 1957 and from 7 to 25 Oct. 1958, and the Alfred Schmela Gallery in Düsseldorf (Germany) in July 1958. And he did represent Canada at the universal exposition in Brussels in May 1958, as he had at the 3rd biennial exposition in São Paulo in July 1955. But it was not until 1959 that a Parisian gallery – the Galerie Saint-Germain – afforded him the honour of a one-man show (20 May–13 June).

Had it not been for the presence of friends such as Robert Élie, Michel Camus, and Marcelle Ferron*, and several visitors from Canada (Gisèle and Gérard Lortie, Max Stern*, Gilbert Blair Laing*), Borduas’s stay in Paris would have been much harder to bear. His health had never been good. Letters written towards the end of his life reveal that he was homesick. As he confessed to Bernard Bernard, a childhood friend, in a letter dated 28 April 1959, he dreamed of “building a studio on the banks of the Richelieu, at the mouth of the little river near Saint-Mathias.”

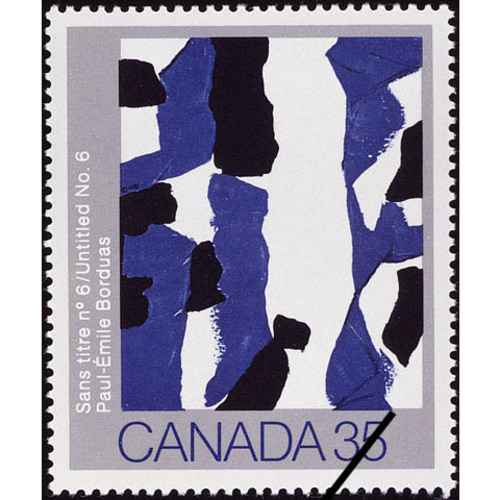

However, once settled in Paris, Borduas had nevertheless modified his style yet again. After a transitional phase that can be seen as extending his New York period, in which his paintings became increasingly all-over (in the sense that the viewer’s eye is drawn from one area to the next, rather than to a focus on one in particular), and displayed an ever-greater use of white, he began to introduce black shapes into his paintings. These shapes were sometimes seen as rents in a white screen, but more often as patches of black against a white ground. In some cases, it is impossible to decide between one reading and the other. Borduas confessed to a Parisian journalist that he was trying to make his paintings “reversible,” so that the same work would lend itself successively to two different interpretations. In 1957 he sometimes used a very dark brown, as in his masterpiece, L’étoile noire. He was now paying more and more attention to the geometric composition of his paintings. Automatism was then a thing of the past for Borduas. He himself recognized that he had been somewhat influenced by Mondrian. His last works were more calligraphic in character. In their own way, they perhaps were a testimony to the Canadian painter’s final dream, never to be realized, of an ultimate exile in Japan.

Paul-Émile Borduas died of a heart attack in Paris on 21 Feb. 1960. In addition to his influence on Quebec thought, he left a considerable body of work, more significant for its originality and its meaning in the history of Canadian art than for the number of paintings. Two major retrospectives were organized immediately after his death. The first, curated by Willem Sandberg, took place in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from 22 Dec. 1960 to 30 Jan. 1961. The second was held in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, on the initiative of its director, Evan Hopkins Turner, from 11 Jan. to 11 Feb. 1962, and thereafter travelled to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (8 March–8 April) and the Art Gallery of Toronto (4 May–3 June). Since the publication of the complete writings of Borduas, the originality of his thought is steadily becoming clearer. Every ten years, there are celebrations commemorating the publication of Refus global, which represented a real intellectual upheaval at the dawn of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec.

The subject’s personal papers and original copies of his written works are held in the Fonds Paul-Émile Borduas at the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal. His writings are the subject of a critical work: P.-É. Borduas, Écrits, ed. A.-G. Bourassa et al. (2v. en 3 tomes, Montréal, 1987–97). A selection of his texts, along with their English translations, has been published in P.-É. Borduas, Paul-Émile Borduas: écrits/writings, 1942-1958, ed. F.-M. Gagnon, trans. F.-M. Gagnon and Dennis Young (Halifax, 1978).

For more information about the artist and his works, the reader should consult in particular the follwing sources: A.-G. Bourassa, Surréalisme et littérature québécoise (Montréal, 1977); Ann Davis, Frontiers of our dreams: Quebec painting in the 1940’s and 1950’s ([Winnipeg], 1979); Robert Élie, Borduas (Montréal, 1943); Ray Ellenwood, Egregore: a history of the Montréal automatist movement (Toronto, 1992); F.-M. Gagnon, Chronique du mouvement automatiste québécois, 1941–1954 (Outremont, Qué., 1998); Paul-Émile Borduas (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1988); Paul-Émile Borduas, 1905–1960 (Ottawa, 1976); Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960): biographie critique et analyse de l’œuvre (Montréal, 1978); Maurice Gagnon, Sur un état actuel de la peinture canadienne (Montréal, 1945); Gilles Lapointe, L’envol des signes: Borduas et ses lettres (Montréal, 1996); Gilles Lapointe et F.-M. Gagnon, Saint-Hilaire et les automatistes (Mont-Saint-Hilaire, Qué., 1997); Gilles Lapointe et Raymond Montpetit, Paul-Émile Borduas, photographe: un regard sur Percé, été 1938 ([Saint-Laurent, Qué.], 1998); Paul-Émile Borduas, 1905–1960 (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1962); Guy Robert, Borduas ([Sainte-Foy, Qué., 1972]); Borduas, ou, le dilemme culturel québécois ([Montréal], 1977).

Soc. de Généalogie de Québec, Fichier Drouin, Notre-Dame (Granby, Qué.), 11 juin 1935; Saint-Hilaire (Mont-Saint-Hilaire), 5 nov. 1905 (mfm.). “M. P.-É. Borduas meurt à Paris à l’âge de 54 ans,” Le Soleil (Québec), 23 févr. 1960.

Revisions based on:

Arch. de Paris, “Actes d’état civil,” 7e arrondissement, 22 févr. 1960, no. 252: archives.paris.fr/s/4/etat-civil-actes (consulted 13 April 2021).

Cite This Article

François-Marc Gagnon, “BORDUAS, PAUL-ÉMILE (baptized Paul-Émile-Charles),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/borduas_paul_emile_18E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/borduas_paul_emile_18E.html |

| Author of Article: | François-Marc Gagnon |

| Title of Article: | BORDUAS, PAUL-ÉMILE (baptized Paul-Émile-Charles) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | March 31, 2025 |