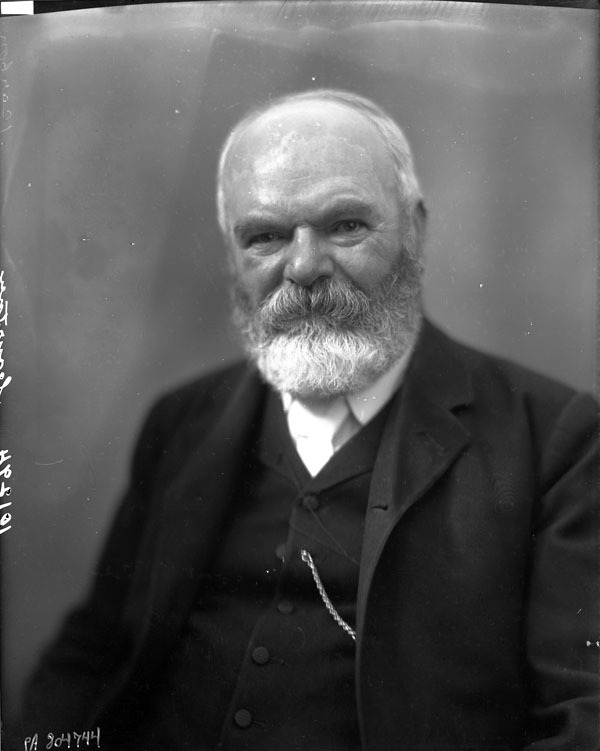

COURTNEY, JOHN MORTIMER, civil servant; b. 22 July 1838 in Penzance, England, second son of John Sampson Courtney and Sarah Mortimer; m. 5 Oct. 1870, in Ottawa, Mary Elizabeth Sophia Taylor, daughter of John Fennings Taylor*, and they had a son; d. there 8 Oct. 1920.

Mortimer Courtney would write in 1888 that banking was a subject dear to his family: his father had been a banker and his elder brother, Leonard Henry, had also worked in a bank and had gone on to become a secretary to the Treasury in William Ewart Gladstone’s second administration. Privately educated in Penzance, Mortimer developed his own interest in banking and, like so many of his generation, he took his ambitions to the colonies, where opportunities for young men with financial aptitude were abundant. He ventured first to India with the Agra Bank and then to Australia.

In 1869, at the invitation of the Canadian minister of finance, John Rose*, he came to Canada and entered the public service on 2 June as chief clerk and assistant secretary to the Treasury Board, under John Langton*. Upon taking office Courtney found most of the country’s financiers rallying against Rose’s attempts to reform Canada’s banking system. In a departmental reorganization that would preoccupy Courtney for much of a year, on 1 Aug. 1878 Richard John Cartwright, minister of finance in the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie*, promoted him deputy minister and ex officio deputy receiver general and secretary to the Treasury Board. The following month the Liberals were defeated.

Courtney’s administrative talents were quickly put to use by the new Conservative government – he was on the team that prepared Samuel Leonard Tilley*’s National Policy budget – but his principles may have contributed to his liberal leanings. Since he had been sympathetic to the Liberal attack on patronage, bankers could no longer count on the relationships they had cultivated with politicians and civil servants to acquire government accounts, deposits, or contracts to exchange Canadian dollars for sterling and thus to sustain public confidence in their institutions. Increasingly value and security were considered before government business went to any bank. On several occasions Courtney spoke out against banks trying to apply political pressure in order to obtain business. When the Western Bank of Canada approached Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* in 1888, for instance, Courtney unequivocally advised him against giving it any business: “Of all the English banks it has the lowest cash reserve against the circulation and deposits.” He also took exception to the charges banks levied to negotiate government cheques. As well, he desired a banking system that complemented rather than competed with the Post Office Savings Bank, a source of cheap money often used to finance public expenditures.

Generally Courtney tried to persuade bankers to see things his way. A far-reaching series of bank failures in the 1880s, however, prompted him to begin work in 1887 on sweeping changes to the Bank Act to assure greater security for depositors, shareholders, and the government. He advocated a safety fund to guarantee the currency of the banks, charters of unlimited duration, a restricted note issue for existing banks, no note issue for new banks, a ten-per-cent fixed reserve, and external audits by accountants hired by shareholders. When word of these proposals emerged, three of the dominion’s most respected bankers, George Hague of the Merchants’ Bank of Canada, Byron Edmund Walker* of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and Thomas Fyshe of the Bank of Nova Scotia, appealed to cabinet to review the changes, particularly the impact of fixed reserves, which, Walker testified, would ruinously reduce the credit available to Canadians.

By the spring of 1890 Courtney had been instructed by his minister, George Eulas Foster*, to abandon much of what he had proposed, but he did find a way to make the banking system more responsive to his department. He encouraged Walker, who had organized bankers in Toronto under the auspices of the city’s Board of Trade, to join with Hague of Montreal. In December 1891 they formed the Canadian Bankers’ Association [see Sir Edward Seaborne Clouston]. Courtney, who would exercise considerable personal influence through this association, saw it as a means of ending the “uneconomic competition” that was blamed for a weak banking system and for runs on deposits in Post Office savings banks in the late 1880s.

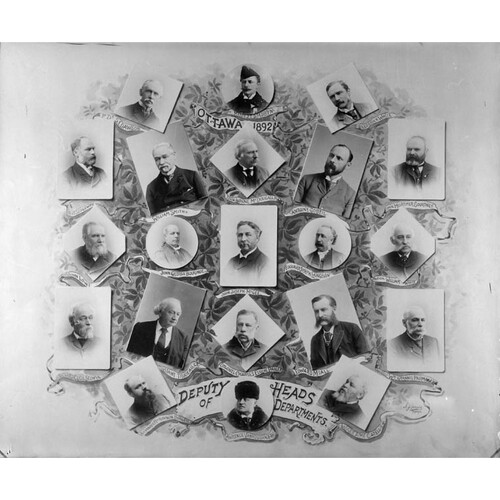

In 1891–92 Courtney and Hague were drawn together again in a federal royal commission on the civil service. More commission work came Courtney’s way in 1897, on the preservation of public records [see Douglas Brymner*], and in 1903, in the inquiry into departmental accounting practices and defalcations in the Department of Militia and Defence. The latter commission drew fire from auditor general John Lorn McDougall*, whose office was criticized and whose relations with Courtney had long been cool.

Courtney remained the devoted bureaucrat, scrutinizing estimates, drafting public accounts, and steadily resisting enormous pressures from within governments to authorize expenditures. His professional resolve was widely known. In a revealing encounter in 1896 at the governor general’s residence, Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*] had privately shown him a set of Treasury minutes and asked if Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] should sign them. As recorded by Sir Joseph Pope*, Courtney, “rather a choleric gentleman at all times, a radical with a high sense of honour, was furious at being made the recipient of this confidence, giving the lady to understand that in the first place she should never have seen those minutes, and secondly that if Lord Aberdeen had any doubts as to the propriety of the recommendations they contained, his proper course was to consult his Prime Minister . . . and not a permanent official like himself.”

For several years Courtney was managing director of the Civil Service Building and Savings Society, and the zeal he showed in his profession extended into various philanthropic interests, among them the Associated Charities of Ottawa and the Canadian Patriotic Fund. Created a cmg in 1897 in recognition of his treasurership of the Indian Famine Relief Fund in Canada, he was made a companion of the Imperial Service Order in 1903. Although he retired in 1906, he was called upon the following year to head another royal commission on civil service reform. This work, which echoed the commission of 1891–92, sparked strong reaction from the Conservative opposition in parliament, some of it aimed, unfairly, at Courtney as a Liberal hack. His report of 1908, which recommended competitive entrance examinations, set a new course for the civil service, one designed to engrain the non-partisan professionalism that had been the mainstay of Courtney’s approach to public service.

Also in 1908 Courtney served on the Quebec battlefields commission and was honorary treasurer of its acquisition fund. An Anglican and a member of the Rideau and Royal Ottawa Golf clubs, he remained active in Ottawa society and resigned as president of the Victorian Order of Nurses only in 1918, at the age of 80. He died two years later and was survived by his son, Reginald Mortimer, a noted civil engineer and militia commander.

John Mortimer Courtney is the co-author, with Adam Shortt*, of the article on “Dominion finance, 1867–1912” in Canada and its provinces; a history of the Canadian people and their institutions . . . , ed. Adam Shortt and A. G. Doughty (23v., Toronto, 1913–17), 7: 471–514.

AO, RG 80-5-0-7, vol.6, f.26. CIBC [Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce] Arch. (Toronto), File information concerning B. E. Walker. NA, RG 19, 2802; 2807; 3196, file 12109. Ottawa Evening Journal, 9 Oct. 1920. Michael Bliss, A living profit: studies in the social history of Canadian business, 1883–1911 (Toronto, 1974). Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1903, 1908. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Canadian who’s who (1910). CPG, 1879, 1891. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. G. P. Gooch, Life of Lord Courtney (London, 1920). J. E. Hodgetts et al., The biography of an institution: the Civil Service Commission of Canada, 1908–1967 (Montreal and London, 1972). Joseph Pope, Public servant: the memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope, ed. Maurice Pope (Toronto, 1960). Norman Ward, The public purse: a study in Canadian democracy (Toronto, 1962).

Cite This Article

John A. Turley-Ewart, “COURTNEY, JOHN MORTIMER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/courtney_john_mortimer_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/courtney_john_mortimer_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | John A. Turley-Ewart |

| Title of Article: | COURTNEY, JOHN MORTIMER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | September 4, 2024 |