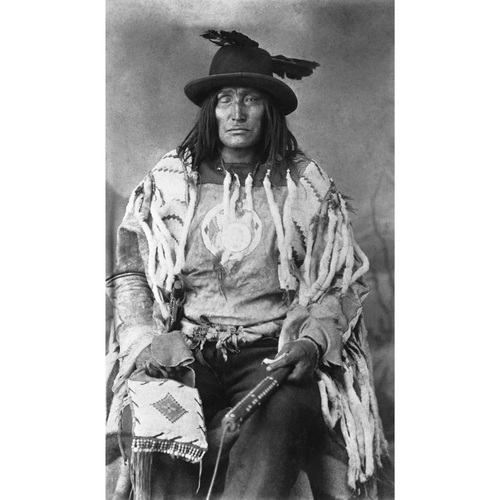

![Bull Head, chief of the Sarcee (Tsuut'ina) [ca. 1890-1894].

Photographer/Illustrator: Ross, Alexander J., Calgary, Alberta.

Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta. Original title: Bull Head, chief of the Sarcee (Tsuut'ina) [ca. 1890-1894].

Photographer/Illustrator: Ross, Alexander J., Calgary, Alberta.

Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.](/bioimages/w600.11403.jpg)

Source: Link

CHULA (Little Chief, Stamixo’tokan, Bull Head), Sarcee warrior and chief; b. c. 1833, likely in what is now central Alberta; had two wives (one a Blackfoot), and two children, both of whom died young; d. 14 March 1911 on the Sarcee Indian Reserve, Alta.

While still a child, Bull Head contracted smallpox during the epidemic of 1837–38. Although he lost his right eye, he survived to win a reputation as a warrior unparalleled in the Sarcee tribe. He took part in thirty battles, killed five enemy, took three scalps, and captured many horses and war trophies. A pictograph robe in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, and another in the Glenbow Museum, Calgary, display his achievements in war.

His elder brother, Chula (Little Chief), was killed by Cree in 1865. By the early 1870s Bull Head had succeeded him as chief of the tribe and taken his name. He was generally known as Bull Head to government officials, however, although he was Little Chief, or Chula, to his own people. Methodist missionary John Chantler McDougall met him north of what is now Calgary in 1872. Some of the Sarcee appeared unfriendly, but McDougall entrusted his horse herd to the chief and spent a peaceful night in his camp.

In 1877, when the Indians of southern Alberta assembled to negotiate a treaty with the Canadian government, Bull Head reluctantly agreed to the terms and signed Treaty No.7 on behalf of his followers, who numbered 255. He had no interest then in the location of a reserve and approved the suggestion of Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*], a Blackfoot head chief, that the Sarcee, Blackfoot, and Blood share a common one near Blackfoot Crossing. However, when confinement to a reserve became a reality in 1879 with the destruction of the buffalo herds in Canada, Bull Head refused to remain near the Blackfoot and demanded location near Fort Calgary (Calgary). After some skilful diplomatic manœuvring on his part the government finally agreed in 1881 to give the tribe three townships of land west of the fort.

For a number of years afterwards, Bull Head was considered to be a fractious chief, yet his so-called obstinacy was usually part of a spirited defence of his people. In 1882 members of his band stole a washtub which they made into a drum. The North-West Mounted Police demanded its return, but Bull Head refused, saying that his tribe needed a drum more than the people of Fort Calgary needed a washtub. Rather than provoke a confrontation, the police dropped the matter. A year later, at a time many Sarcee were starving, a man named Crow Collar broke into the ration house and angrily damaged the weigh scales. When the police tried to apprehend him, Bull Head refused to give him up. Superintendent John Henry McIllree then tried to arrest the chief. A number of young warriors came to Bull Head’s aid, and with the chief pointing his rifle at the officer, the heavily armed police were forced to withdraw. Crow Collar was surrendered the following day and Bull Head came in a day later, accompanied by virtually the entire tribe. Crow Collar was sentenced to ten days’ imprisonment, but Bull Head was released after only two days in confinement. “I would strongly recommend that this Chief be deposed,” stated McIllree. “He is a very bad man and exercises a most pernicious influence over his people.” However, no further action was taken.

In 1885 the authorities were apprehensive that the Sarcee might join Louis Riel*’s forces in the North-West rebellion. Even though Bull Head wore the medal given to him at the 1877 treaty and proclaimed his desire to maintain peace, his followers were initially discouraged from coming into Calgary. Once the chief had met with the military authorities, however, the Sarcee made regular visits to town to put on dances in exchange for food.

One of Bull Head’s most serious and consistent problems as chief was the tribe’s proximity to the town of Calgary. Bootleggers and riff-raff were constantly encouraging prostitution and selling illicit liquor. On a number of occasions Bull Head himself was arrested and jailed for the use of alcohol. As a rule, however, he tried to control the social conditions on his reserve, but starvation and disease, particularly tuberculosis, remained troublesome during his lifetime. In 1895 Indian agent Samuel Brigham Lucas* observed that the Sarcees’ overwhelming difficulties had caused some people to give up. “Until recently they believed themselves doomed to extinction in the near future,” he said, “and did not appear to wish to exert themselves to avoid what they considered to be their inevitable fate.”

Throughout the three decades after the Sarcee settled on their reserve, Bull Head’s main complaint was the lack of food. Employment opportunities were limited and agriculture was only marginally successful, so the tribe had to rely on government rations. In 1885 he told the authorities that the best way to keep its members peaceful was to see they were well fed. During the rebellion, rations were doubled, but they were reduced again after it was over. When Lord and Lady Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*; Marjoribanks*] visited the Sarcee in 1895, Bull Head complained that his people were not being adequately paid for their hay and were kept poor while neighbouring tribes got rich. In 1901, speaking at a reception for the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall in Calgary, he again pursued the problem of inadequate rations.

At the same time Bull Head encouraged self-sufficiency within the tribe. In 1884 the Indian agent reported that the chief got the people working in their gardens and planting small plots of grain. He also urged them to build houses to replace their worn lodges. To set an example, he had the first log house on the reserve. In 1888 the agent commented that the chief “always assists in getting the other Indians to attend to their fields, etc. Has the reputation of being troublesome in older times but of late has been very quiet indeed.”

Although Bull Head remained with his native religion, he permitted missionaries to come to his reserve and encouraged children to go to school. Harry William Gibbon Stocken, an Anglican minister who laboured on the reserve from 1888 to 1895, found the chief demanding but friendly. At their first meeting Bull Head would not eat at Stocken’s table until he knew the missionary’s intentions. If he did not agree with his plans, he would not accept his food. Later he relied on the missionary to provide much-needed tea for the camp, and when Stocken was being transferred to another reserve begged him to stay.

In 1904 the federal government urged the Sarcee to surrender part of their reserve so that the funds could be used to buy cattle and farm equipment. While some of the younger Indians agreed, Bull Head was entirely opposed. “We are of one mind not to sell or give up any of our Reserve,” he said. “We don’t want to quarrel about it. The Reserve is just big enough for ourselves; the whitemen are bothering us to give up our land. The Treaty was made. We don’t want to sell.” When Bull Head died in 1911, his tribe had not relinquished any of the reserve and, indeed, its members had created a large cairn to remind them to keep their lands.

Bull Head was described as “extremely tall, well over six feet two inches in his old age, and very broad shouldered,” with “a loud booming voice.” He had a commanding personality: according to elders, people did what he told them to do. Perhaps his greatest contributions were in keeping the Sarcee united and his reserve intact in spite of devastating social and health problems and the pressures of Calgarians who coveted their lands.

At the request of Edmund Montague Morris, Bull Head himself sketched the highlights of his warrior days on the buffalo robe that is now held by the Ethnology Dept. of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (Edmund Morris coll., HK 459), and he allowed Morris to do the portrait in the same collection (HK 2410). A striking photograph of the chief is in the PAA.

NA, RG 10, 1627: 501; 1628: 57; RG 18, 1007, file 397. Calgary Herald, 3 Oct. 1901, 29 April 1933. Manitoba Free Press, 14 Aug. 1895. Arni Brownstone, War paint: Blackfoot and Sarcee painted buffalo robes in the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, 1993). Can., Dept. of Indian Affairs, Annual report (Ottawa), 1895: 78. Diamond Jenness, The Sarcee Indians of Alberta (Ottawa, 1938). J. [C.] McDougall, In the days of the Red River rebellion: life and adventure in the far west of Canada (1868–1872) (Toronto, 1903; repr. 1911; repr., intro. Susan Jackel, Edmonton, 1983). J. W. G. MacEwan, Portraits from the plains (Toronto, 1971). E. M. Morris, The diaries of Edmund Montague Morris; western journeys, 1907–1910, transcribed by Mary Fitz-Gibbon (Toronto, 1985) [portrait of subject reproduced on p.29]. E[dward] Sapir, “Personal names among the Sarcee Indians,” American Anthropologist (Menasha, Wis.), new ser., 26 (1924): 108–19. C. Æ. Shaw, Tales of a pioneer surveyor, ed. Raymond Hull (Don Mills [North York], Ont., 1970). H. W. G. Stocken, Among the Blackfoot and Sarcee (Calgary, 1976). E. F. Wilson, “The Sarcee Indians,” Our Forest Children ([Sault Ste Marie, Ont.]), 3 (1889–90): 97–102.

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “CHULA (Little Chief, Stamixo’tokan, Bull Head),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chula_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chula_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | CHULA (Little Chief, Stamixo’tokan, Bull Head) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |