Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

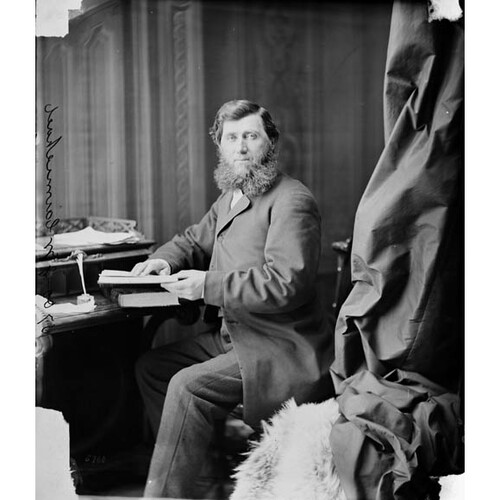

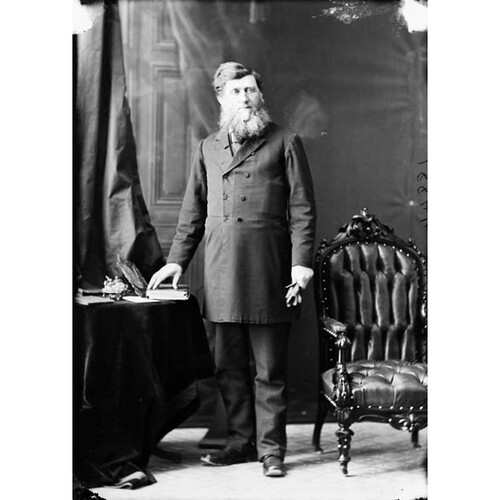

CARMICHAEL, JAMES WILLIAM, businessman and politician; b. 16 Dec. 1819 in New Glasgow, N.S., elder of the two sons of James Carmichael* and Christian McKenzie; m. 5 June 1851 Maria Jane McColl (d. 1874) in Guysborough, N.S., and they had one son and five daughters; d. 1 May 1903 in New Glasgow.

The son of the founder of New Glasgow, James William Carmichael attended Pictou Academy [see Thomas McCulloch*], and then became a clerk in his father’s store and “occasionally went as supercargo” on his vessels. He gradually took over his father’s mercantile and shipping businesses in the early 1850s, and by 1854 the firm was known as J. W. Carmichael and Company. Carmichael’s brother, John Robert, became a partner sometime afterwards, but left in 1863. George Rogers McKenzie*, Carmichael’s maternal uncle and a prominent New Glasgow shipbuilder and ship’s captain, had a loose business association with Carmichael and his father and constructed some of his vessels in their yard. The relationship between McKenzie and Carmichael, who later acquired his uncle’s business, was particularly close, and Carmichael honoured McKenzie by flying the initials GK on his house-flag for nearly half a century.

The first vessel registered in Carmichael’s name was the 129-ton Helen Stairs of 1851, and from 1857 to 1869 he built at least 14 more. His ships conducted an extensive trade in supplies from Pictou County to the lumber camps of the Miramichi River, N.B., and during the period of operation of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States (1854–66) they also transported coal from the Pictou fields to American markets. Although the building and use of wooden ships declined in the 1870s, Carmichael remained active. By then his yards were the most important in Pictou County, and he constructed his largest vessel, the 1,174-ton Thiorva, in 1876.

New Glasgow’s shipping industry stood out in the Maritimes because a larger number of its vessels were owned locally and because its peak of construction occurred in the mid 1850s, relatively early compared with the course of building in other ports. The latter development has been attributed to the increase in outlets for investment caused by the growth of the region’s land-based economy, in particular the development of the coal industry, and the consequent withdrawal of capital from shipbuilding. Carmichael was attracted by these opportunities from the beginning of his business career and through them he broadened his investment base. Involvement with the land-based economy was in fact characteristic of Nova Scotian shipowners, who were prominent in developing the towns in which they were located.

One of Carmichael’s first entries into a non-mercantile field was his acquisition of an extensive lease of coal-producing areas after the abrogation of the monopoly of the General Mining Association in 1857. He attempted some development and expended $3,200, but like many in the region eventually sold the lease to an intermediary, who in turn sold it to a foreign syndicate. When Graham Fraser* and George Forrest McKay, who had ironed ships in Carmichael’s yard, established the Nova Scotia Steel Company in 1883, Carmichael contributed $10,000, and the following year his son, James Matheson, became a director. During the late 1880s, however, the Carmichaels cautioned against the company’s plans to produce iron locally, and in 1894 James Matheson resigned over a financial dispute. Carmichael was a minor shareholder in the Nova Scotia Glass Company [see Harvey Graham], which he supplied with boxes for packing the glass. He likewise took part in the export trade in lumber, establishing the first steam sawmill in Pictou County in 1874, and between 1883 and 1892 he operated the New Glasgow Tannery Company in partnership with James C. McGregor. Carmichael’s major involvement with industry, however, was with the Acadia Iron Foundry, founded by his brother-in-law Isaac Matheson in 1867. The firm, later I. Matheson and Company, became a prominent manufacturer of boilers.

Notwithstanding this support of local firms, Carmichael indulged in manufacturing only as a complement to his main lines of business. His agency for the Bank of Nova Scotia (1866–86) as well as his presidency of the New Glasgow Marine Insurance Association and his chairmanship of the New Glasgow Underwriters’ Association were similarly tied to his principal interests.

Although deeply committed to wooden sailing-ships during the heyday of the industry, Carmichael had from an early date been interested in vessels which employed new technologies. In 1854 and 1865, for example, McKenzie and Carmichael had constructed steamers for the ferry service which connected New Glasgow and Pictou with Prince Edward Island. Carmichael stopped building wooden vessels in 1883 and, like many other Nova Scotian shipowners, began placing orders with prominent builders of iron ships on the Clyde River in Scotland. In 1885 he had constructed the Brynhilda, the first iron ship built for and owned by a Nova Scotian. He and I. Matheson and Company were active in lobbying the provincial government to promote the use of iron and steel steamers. The company in fact pioneered the construction of steel steamers in Nova Scotia, its largest, the 485-ton Mulgrave, being built in 1893 for Carmichael’s firm. In 1898 James Matheson Carmichael analysed the prospects for a Nova Scotian shipbuilding industry based on steel and steam. He boldly predicted “We will have half a dozen shipyards within the next ten years” and lamented that 20 years had been lost to the industry because shipbuilders had preferred to invest in cotton factories and sugar refineries, “[from] the management of which we have perhaps not gained much glory and less profit.” But the Carmichaels were ambivalent about their allegiances. While insisting that government support was necessary in order to stimulate domestic production, they rejected Canadian independence of British vessel registration, though such independence was also necessary to prevent Canadians from buying and registering ships in Britain, the older Carmichael arguing, for example, against the establishment of a Canadian Lloyd’s register of shipping.

By diversifying his investments, Carmichael was able to maintain his position in Pictou County, and his worth grew steadily. In 1872 his combined assets were valued at just over $183,000; by the time of his death they had grown to nearly $583,000. The firm of J. W. Carmichael and Company continued – its iron and steel vessels would be active in international shipping until World War I – but the members of his family became rentiers, collecting dividends through a firm of Halifax stockbrokers. In 1962 the firm went into voluntary liquidation, and $670,000 was bequeathed to charitable organizations.

Although Carmichael and the New Glasgow mercantile community financed local industrialists and welcomed them into their families, they were less inclined to agree with their politics. The merchants were Liberals and uncompromising supporters of free trade, the industrialists Conservatives and protectionists. Carmichael himself supported the Liberals after his election to parliament for Pictou in 1867 as an opponent of confederation. Ousted in 1872 and reelected in 1874, he was defeated in the general elections of 1878, 1882, and 1896, and in a by-election in 1881. Carmichael was undismayed by his frequent losses, which were caused in part by quarrels among the Liberals and in part by the fact that Pictou County was benefiting from the National Policy of the Conservatives. He remained a key figure in the provincial and national parties, and he was on good terms with Edward Blake*, Alexander Mackenzie*, and Wilfrid Laurier*. In parliament he spoke in favour of free trade and Maritime rights, objecting to “Nova Scotia occupying a position of inferiority and existing by sufferance.” His most controversial stand was in 1876, when he opposed a tariff on coal that the Conservatives had proposed in order to help market Nova Scotian coal in central Canada. Carmichael argued that it was impossible to organize trade between Ontario and Nova Scotia because of the difficulties of transportation and added that it was preposterous to think that Nova Scotian coal could compete with American coal merely because of the duty of 50 cents a ton. This stand cost him electoral support in a region highly dependent on the coal industry and caused him to be burned in effigy by a group of coalminers. In 1898 Carmichael was appointed to the Senate, from which he resigned a week before his death.

Carmichael was active in the community life of New Glasgow. Lieutenant-colonel of the 5th Regiment of Pictou militia, vice-president of the Pictou County Rifle Association, and a member of the council of the Nova Scotia Rifle Association, he was also a founding director of the Aberdeen Hospital and president of the New Glasgow auxiliary of the British and Foreign Bible Society. In religion he was an anti-burgher Presbyterian, and joined Primitive Church when it was founded in 1845. Carmichael took part in the negotiations which merged Knox and Primitive churches in 1874 as the United Church, and he was subsequently chairman of its board of trustees until his death. In 1875 he was one of those behind the drive for incorporation of the town, and he served as a fire warden and a trustee of public property.

In 1903 Carmichael died peacefully at his home. He left a legacy of charitable and religious work, but he had been first and foremost a businessman. His only son having predeceased him, the family was represented in the 20th century by his daughters, who made a reputation as reformers, social activists, and supporters of charities and the arts. Caroline Elizabeth, for example, became president of the National Council of Women of Canada and was awarded an honorary doctorate by Dalhousie University. She nevertheless remained faithful to her past, gave generous support to the Liberals, and, in later years, was described as a “lady in dark clothes” driven by a uniformed chauffeur.

NA, RG 31, C1, 1871, Pictou, N.S. PANS, MG 2, 224–368. Eastern Chronicle, 4 May 1903. Free Lance (Westville, N.S.), 18 Sept. 1913. Halifax Herald, 21 Aug. 1898, 2 May 1903. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 31 March, 2 May 1903. Pictou Advocate, 1 May 1903. C. A. Armour and Thomas Lackey, Sailing ships of the Maritimes . . . 1750–1925 (Toronto and Montreal, 1975). J. M. Cameron, About Pictonians (Hantsport, N.S., 1979); More about New Glasgow ([New Glasgow, N.S.?], 1974); The Pictonian colliers (Halifax, 1974); Political Pictonians: the men of the Legislative Council, Senate, House of Commons, House of Assembly, 1767–1967 (New Glasgow, [1967]); Ships and seamen of New Glasgow, Nova Scotia (New Glasgow, 1959); Still more about Pictonians (Hantsport, 1985). Industrial Advocate (Halifax), March 1899: 7–9. L. D. McCann, “The mercantile-industrial transition in the metals towns of Pictou County, 1857–1931,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 10 (1980–81), no.2: 29–64. L. [D.] McCann and Jill Burnett, “Social mobility and the ironmasters of late nineteenth century New Glasgow,” People and place: studies of small town life in the Maritimes, ed. L. [D.] McCann (Fredericton and Sackville, N.B., 1987), 59–77. Ian McKay, “The crisis of dependent development: class conflict in the Nova Scotia coalfields, 1872–1876,” Canadian Journal of Sociology ([Edmonton]), 13 (1988): 9–48. G. E. G. MacLaren, “Shipbuilding on the north shore of Nova Scotia” (typescript, Halifax, 1962; mfm. in PANS, Library, M162). R. E. Ommer, “Anticipating the trend: the Pictou ship register, 1840–1889,” Acadiensis, 10, no.1 : 67–89. E. R. Sager with G. E. Panting, Maritime capital: the shipping industry in Atlantic Canada, 1820–1914 (Montreal, 1990). J. H. Sinclair, Life of James William Carmichael, and some tales of the sea (Halifax, [1911]).

Cite This Article

L. Anders Sandberg, “CARMICHAEL, JAMES WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carmichael_james_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carmichael_james_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | L. Anders Sandberg |

| Title of Article: | CARMICHAEL, JAMES WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |