Source: Link

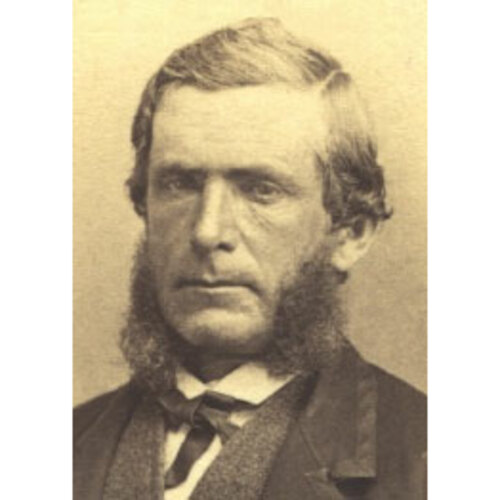

RICHARDSON, JAMES, tailor, businessman, and politician; b. 1819 in Aughnacloy (Northern Ireland), son of Daniel Richardson and Janet Armstrong; m. first 1 March 1845 Roxanna Day (d. 1848) in Kingston Township, Upper Canada, and they had a son, who died in infancy, and a daughter; m. secondly 11 March 1850, in Kingston, Susannah Wartman, a niece of his first wife, and they had two sons; d. there 15 Nov. 1892.

In 1822 or 1823 James Richardson immigrated to Upper Canada with his father, his sister, and his half-sister Elizabeth. The family settled in the Adolphustown district, where Daniel Richardson died in 1826, leaving Eliza, still in her teens, in charge of her two younger siblings. By 1829 she had moved the family to Kingston. Brought up there by a sister of his father, James received limited formal education. As a youth he sold newspapers and was apprenticed to a tailor, John Dawson. The connection was an important one: Mrs Dawson was a member of the Wartman family as were both of Richardson’s future wives.

Richardson was in business by 1841, in which year he and William Sanderson were fined £5 for “hawking and pedling without license.” Briefly he was in a tailoring partnership with a Mr Little and in 1844, according to an advertisement in the Chronicle & Gazette, he went into business on his own as a merchant tailor. He continued to advertise his wares in the local press and, clearly, he was prospering and expanding. By 1848, when he was 29, he owned the property occupied in part by his business; he lived above his shop and had several merchants as tenants. At some point he began dabbling in grain, since his customers occasionally paid him in that medium. One indication of his success came in 1856 when he stood as a guarantor for the construction of a new custom-house in Kingston. The contractor, Thomas C. Pidgeon, proved unable to overcome various difficulties, the other guarantors (James O’Reilly* and Samuel Smyth) reneged, and in the end Richardson completed the work. He had done so by September 1858, but at a loss of more than £1,700.

Richardson’s financial burden in building the custom-house had apparently forced him to find new sources of income. On 31 Dec. 1856 he mortgaged his Brock Street property to his half-sister for £750. He also became involved in the grain trade, although he continued his tailoring and building activities into the 1860s. He is not referred to as a grain dealer in Kingston directories until 1865, but a company history dates to 1857 the founding of the family grain firm that would become James Richardson and Sons. The first entry for this company appears in the Kingston directory of 1873–74, which refers to “richardson & sons, Grain Dealers, Commercial Wharf, foot of Princess St.” By this time Richardson’s two sons, George Algernon and Henry Wartman, had become full partners.

Richardson began to make his mark in business during the years of Kingston’s determined struggle to attain a regional and national role. At the same time he became involved in the town’s religious and municipal life. A Wesleyan Methodist, he was a member of Sydenham Street Church, where he taught Sunday school and to which he was a liberal contributor. He was present at the inaugural meeting of the Board of Trade on 22 Aug. 1851. Although there is no evidence that he became active on the board, in May 1872 he was part of its four-man committee on harbour improvements, which recommended dredging Kingston Harbour “for the proper safety of the large class of vessels that now trade to this port.” The committee also recommended the construction of a breakwater, extending half a mile from the shore by Murney Tower, at a cost of $40,000. Richardson had become active in municipal politics in the 1860s. He was councilman for St Lawrence Ward in 1860 and alderman for the same ward in 1861; he joined city council again, as alderman for Victoria Ward, in 1870–74. A Tory, Richardson was close to long-time Kingston mp Sir John A. Macdonald. On one occasion in 1889 the prime minister noted to a colleague, “The Richardsons are & always have been strong & influential friends of mine.” On another occasion that year he warned an associate, “Don’t get me into a scrape with the Richardsons. They are my pillars in Kingston.”

Richardson’s growing interest in grain coincided with a boom in Upper Canadian barley, especially that from the region around the Bay of Quinte, which began in the 1860s. The barley, which was of high quality and was purchased in great quantity and at premium prices by American manufacturers, remained an important export commodity until the trade was ruined by American tariffs in the 1890s. During this period Richardson developed a lake fleet that comprised rented and company-owned sloops and schooners capable of carrying from 1,000 to 20,000 bushels. It also included a number of hookers, the firm’s famous “mosquito fleet,” which worked the shores and rivers from the Bay of Quinte to the Rideau Canal. Some grain went directly from the place of collection to an American port, often Oswego or Cape Vincent, N.Y., but much was unloaded at Richardson’s dock in Kingston – or, later, stored in his grain elevator – for trans-shipment to American or European destinations. His waterfront property at the foot of Princess Street, purchased in 1868, was the site of his first elevator; Richardson No.1, built in 1882, with a capacity for 60,000 bushels, quickly became the heart of his grain business. It burned in 1897, five years after his death, but was soon replaced by an elevator of 250,000-bushel capacity.

The Prairie region was not a major grain producer during Richardson’s lifetime, but he did recognize its increasing potential. In 1923 his grandson James Armstrong Richardson*, then president of the firm, would tell a Liverpool businessman, A. R. Bingham, that “the first Western Canadian wheat shipped out of Fort William [Thunder Bay] was in the fall of ’83, and . . . this wheat, which was the first Western Canadian wheat shipped from this continent[,] was shipped by our house to the Atlantic Seaboard in the winter of ’84 and consigned to your house in Liverpool.” Until the 20th century, the western business of the Richardson firm was under the care of Edward O’Reilly, a resident of Wolfe Island (near Kingston) who had moved to Manitoba during the early 1880s. In addition to Britain and the United States, Richardson exported grain to firms in Holland, Switzerland, France, Norway, and Argentina.

Richardson traded in products other than barley and wheat, among them potash, hay, furs, apples, coal, lye, and maple syrup, but he diversified his interests well beyond commodity trading. Substantial amounts of property in the Kingston region were acquired by him. He invested in the Kingston and Pembroke Railway, the Kingston Street Railway Company, the locomotive works at Kingston, the local woollen mill, the Kingston Hosiery Company, and the Kingston Oil and Enamel Cloth Company. In 1881 he became president of the Kingston Cotton Manufacturing Company. As well, Richardson initiated his firm’s interest in mineral development in the Canadian Shield region north of Kingston, an interest that continued well into the 20th century. Perhaps the most productive – and certainly the most prominent – of the firm’s mineral enterprises was the feldspar mine in Bedford Township. Acquired in the 1880s, the Richardson Mine of the family’s Kingston Feldspar Mining Company did not, however, commence operation until 1900. The evidence of Richardson’s son George before the provincial royal commission on mineral resources in 1889 indicates his familiarity with local mining activities. He claimed then to “have seen nearly all the mines in the Frontenac section and [to] have handled the product of pretty much all the phosphate mines in this part of the country.” In the early years of the 20th century the Richardson firm would expand into mica and zinc.

When James Richardson died in 1892, his two sons were still equal partners in the firm. Most of his share of the company was left to his wife, with the provision that it go to their sons on her death. George A. Richardson succeeded his father as company president (1892–1906) and he was followed by Henry W. (1906–18). James Richardson had managed to shift from traditional commercial trading to investment in various enterprises associated with the new industrial age. Moreover, he had been stimulated to invest in Kingston when it was approaching its period of commercial dominance, founding in the process the base for one of Canada’s most important corporate instruments in the 20th century.

Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada. Cataraqui Cemetery Company (Kingston, Ont.), Card index; Reg. of burials, vol.1. Frontenac Land Registry Office (Kingston), GR 1128, will of James Richardson. James Richardson and Sons Limited Arch. (Winnipeg), “James Richardson and Sons Limited, 1857–1957” (typescript, 1940; revised 1957). Kingston Public Library, E. E. Horsey, “Cataraqui, Fort Frontenac, Kingstown, Kingston” (1937). NA, MG 26, A, James Richardson and Sons to George Taylor, 5 Aug. 1889; George Richardson to Taylor, 19 Oct. 1889 (mfm. at QUA); RG 31, C1, 1871, 1881, 1891, Kingston. Private arch., Neil Patterson (Kingston), Mining records; Margaret [Sharp] Angus (Kingston), Family files. QUA, 100, esp. assessment rolls, 1843, 1847, 1850–52, 1855, 1857, 1860, 1865, 1870, 1872, 1875, 1880, 1885, 1890, and minutes of council; 111a, minute-book; 2285, J. H. Aylen, “Custom House Kingston, 1800–1859” (typescript, 1972) and “Kingston Custom House,” 12 Oct. 1972.

Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, 1885, no.30; Royal commission on the mineral resources of Ontario and measures for their development, Report (Toronto, 1890). Argus (Kingston), esp. 15 May, 3 Nov. 1846. Banner (Toronto). Christian Guardian. Chronicle & Gazette (Kingston), esp. 21 Nov. 1841. Daily British Whig, esp. 16 Nov. 1892, 22 Sept. 1904. Daily Free Press (Winnipeg). Financial Post (Toronto), 4 Dec. 1976. Toronto Daily Mail. Kingston directory, 1855–94. Mercantile agency reference book, 1864–93. Buildings of architectural and historic significance (5v., Kingston, 1971–80), 1. Patrick Burrage, 125 years of progress (Winnipeg, 1982). Ont., Dept. of Mines, Annual report, 1947, pt.vi, W. D. Harding, “Geology of the Olden–Bedford area” (repr. 1951). B. S. Osborne and Donald Swainson, Kingston: building on the past (Westport, Ont., 1988). H. S. de Schmid, Feldspar in Canada (Ottawa, 1916); Mica, its occurrence, exploitation and uses (2nd ed., Ottawa, 1912). Robert Collins, “The shy baroness of brokerage,” Maclean’s (Toronto), 70 (1957), no.12: 20, 76–80. Donald Swainson, “James Richardson: founder of the firm,” Historic Kingston (Kingston), no.38 (1990): 95–110.

Revisions based on:

Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R233-34-0, Ont., dist. Frontenac (65), subdist. Wolfe Island (d), div. 1: 25. Man., Dept. of Justice, Vital statistics agency (Winnipeg), no.1904-004121.

Cite This Article

Brian S. Osborne and Donald Swainson, “RICHARDSON, JAMES (1819-92),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 10, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_james_1819_92_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_james_1819_92_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian S. Osborne and Donald Swainson |

| Title of Article: | RICHARDSON, JAMES (1819-92) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | April 10, 2025 |