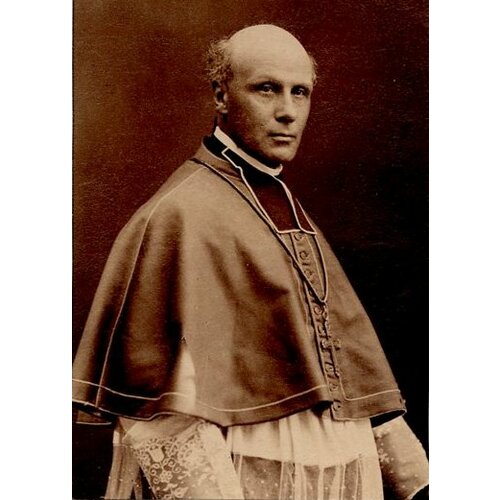

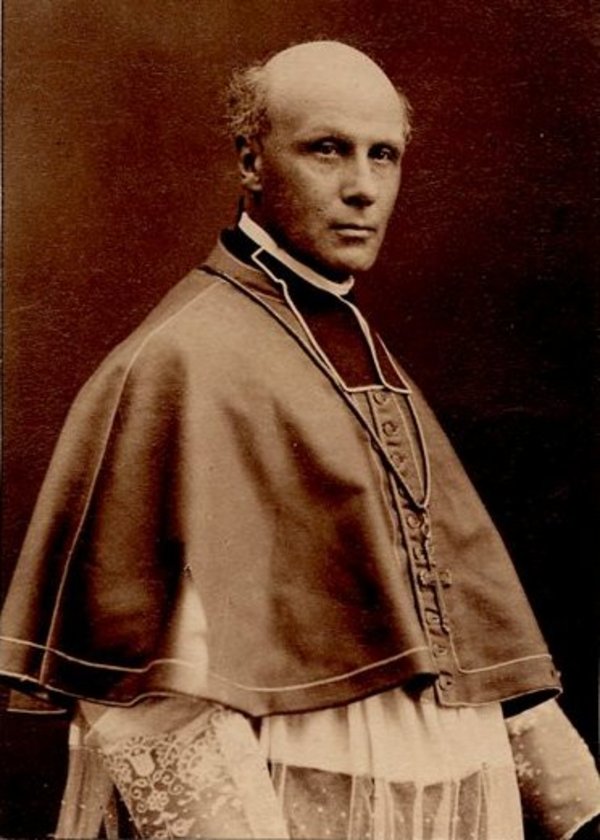

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

RACINE, ANTOINE, Roman Catholic priest, bishop, and educator; b. 26 Jan. 1822 in Saint-Ambroise (Loretteville), Lower Canada, son of Michel Racine, a blacksmith, and Louise Pepin; d. 17 July 1893 in Sherbrooke, Que.

The son of a poor family, and raised by a mother who was widowed during his childhood, Antoine Racine experienced the privations of a modest life. During the winter of 1833 he began to study Latin at the presbytery of his great-uncle, Antoine Bédard, curé of Saint-Charles-Borromée parish in Charlesbourg. He was admitted to the Petit Séminaire de Québec in 1834 and then studied theology at the Grand Séminaire. Ordained to the priesthood on 12 Sept. 1844, he served as curate of Saint-Étienne in La Malbaie (1844–48), first curé of Saint-Eusèbe in Princeville (1848–51), curé at Saint-Joseph in the Beauce region (1851–53), and priest in charge of Saint-Jean-Baptiste church at Quebec (1853–74).

On 1 Sept. 1874 Racine was elected bishop of the new diocese of Sherbrooke, created on 28 August. Consecrated on 18 October by Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau of Quebec, he took charge of his see two days later. The diocese had some 30,000 Catholics, with 29 priests ministering in 29 parishes and five missions. The town of Sherbrooke was becoming a small industrial centre, but much of the hinterland awaited colonization.

While setting up diocesan administrative bodies, creating parishes, founding missions, providing for the material support of the parishes and the clergy, and establishing a uniform ecclesiastical discipline, Racine worked from the beginning of his episcopacy on various educational institutions necessary for the development of his young diocese. The first and most important of these, in the bishop’s eyes, was undoubtedly the Séminaire Saint-Charles-Borromée, which opened in September 1875. He himself served as its superior until 1878 and he undertook the task of teaching theology until 1885.

Bishop Racine also had to attend to the education of the people. Since 1857 girls had had the advantage of being taught by the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, at Mont-Notre-Dame, but a Catholic and French education for boys posed a problem. Both Catholic and Protestant school trustees served on a single committee, responsible for all educational matters. In the spring of 1876 it was recommended to the bishop that they be put on separate committees, which was the practice at Quebec and Montreal. After the necessary authorization had been obtained from the government, the properties and money were divided in proportion to the number of pupils from each religious group. The eastern and northern wards now had their own Catholic schools. The more heavily populated southern one was not provided with a Catholic school until 1882 and it was at Racine’s prompting that the Brothers of the Sacred Heart agreed to take charge of it.

In December 1881 Racine asked the Ursulines at Quebec to send some of their number to his diocese; they had already done so for the diocese of Chicoutimi, where his brother Dominique* was the bishop. He repeated his request in January 1882, asking them to come to Stanstead, near the American border. The Ursulines arrived there in the fall of 1884 and established a convent and a school. On 21 April 1875, at Racine’s request, four nuns from the Hôtel-Dieu in Saint-Hyacinthe moved into a house in Sherbrooke that he put at their disposal. They were to look after the poor, the sick, and the infirm at the Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur.

Colonization was also one of Racine’s major concerns. At La Malbaie he had been the leading spirit in the Société des Défricheurs de la Rivière-au-Sable, formed to open up the land in the future township of Jonquière. In 1851, under his guidance, Le Canadien émigrant, a colonization manifesto, had been published and created a stir. For him, colonization included the progress of agriculture and the development of new areas as well as the repatriation of French Canadians who had gone to the United States. His circular letter to the clergy of his diocese dated 29 March 1875 described colonization as “a national task” and “a task worthy of [their] holy mission and of all God’s blessings.” In order to ensure its success, he urged his curés to establish a small colonization society in every parish, as envisaged in a provincial law that had just been passed. He ordered them to give him full information about available land and property up for sale. In 1880 he informed his clergy that such societies had been founded in Montreal and at Quebec, and that Sherbrooke had organized its own on 14 April to colonize Woburn Township, which would soon be linked by a good road with the new settlements of La Patrie, Notre-Dame-des-Bois, and Piopolis. Repeating what he had done before, he instituted an annual collection to raise money for colonization. The results, however, fell far short of his expectations.

Other major contemporary issues of a much thornier kind held Racine’s attention. In 1874 the conflict between Archbishop Taschereau and the Université Laval on the one hand, and the supporters of an independent Catholic university at Montreal, led by Bishop Ignace Bourget*, on the other, had still not been settled. Racine first took a stand, albeit a moderate one, for Quebec. In 1881 he went to Rome as Taschereau’s representative to defend the interests of the Université Laval. His intention at the time was to obtain a firm decision settling the dispute once and for all, through an apostolic delegate if necessary. Circumstances changed with the creation of the ecclesiastical province of Montreal in 1886 and still more with the publication of the papal bull Jamdudum in February 1889, placing the Montreal branch campus under the jurisdiction of the bishops of that province [see Thomas-Edmond d’Odet d’Orsonnens]. In 1891 Racine, now suffragan bishop of Montreal, was in Rome again, this time to uphold the cause of Montreal. The new situation and the interests of his own diocese explain this apparent reversal.

The bishops were also divided politically and the division long preceded Racine’s election to the see of Sherbrooke. Bourget and later Bishop Louis-François Laflèche of Trois-Rivières were the leaders of the ultramontane element and opposed the Liberals. Bishop Jean Langevin of the diocese of Rimouski favoured the Conservatives and Archbishop Taschereau leaned towards the Liberals. Racine, while supporting like most of his colleagues the exclusive jurisdiction of bishops over their priests, as early as 1875 ordered his clergy to remain strictly neutral in politics. Three years later he asserted, “The clergy must in their public and private lives, in questions that in no way concern religious principles, faithfully observe the prescriptions of our church councils regarding political elections.” He clearly forbad any intervention. In 1881 he declared, “Any priest who, without episcopal authorization, teaches from the pulpit or elsewhere that it is a sin to vote for a particular candidate or political party, or who announces that he will withhold the sacraments for this reason, will ipso facto be suspended.” On 2 Aug. 1886, just before the provincial election, he reminded his priests of the need to follow “the line of conduct set out by the Holy See” and added, “Never give your opinion from the pulpit” and “Do not attend any political meeting.”

Worn out by his duties, Bishop Racine died on 17 July 1893 at his episcopal palace after an illness of only a few days. By this time the diocese was well established. It had some 60,000 Catholics, 45 parishes (almost all erected under both canon and civil law), and 17 missions served by 64 of the 80 priests in the diocese. Eight priests were attached to the seminary to teach the 225 pupils studying there. Eleven candidates were preparing for the priesthood, including two deacons and a subdeacon.

Bishop Antoine Racine was profoundly influenced by the period in which he lived. He made its concerns his own and, in turn, had a noticeable influence on its events. His career provides a good illustration of late-19th-century clerical nationalism in Quebec. He was one of those men for whom love of country and love of the church are one and the same. Enterprising, determined, and courageous, he gave solid roots to a Catholic diocese and French culture in a region where the English Protestant presence was predominant, while still maintaining excellent relations with this religious and cultural group. His achievements, and, above all, the ideas he promoted in his speeches and writings had a lasting influence on colonization. A man of peace and conciliation, without compromising justice or efficiency, he always sought and often succeeded in obtaining, not without difficulty, harmonious and fruitful solutions.

ANQ-Q, CE1-28, 27 janv. 1822. Arch. de la chancellerie de l’archevêché de Sherbrooke (Sherbrooke, Qué.), Fonds Antoine Racine, VII, B, B1; Insinuations, 1; Reg. des lettres, 1. Arch. du séminaire de Sherbrooke, P47 (Antoine Racine); R1 (évêques de Sherbrooke). Mandements, lettres pastorales, circulaires et autres documents publiés dans le diocèse de Sherbrooke (24v., Sherbrooke, 1874–1967), 1–3. Principaux discoursed Mgr Antoine Racine . . . , C.-J. Roy, édit. ([Lévis, Qué.], 1928). Séminaire Saint-Charles-Borromée, Annuaire (Sherbrooke), 1885–86; 1892–93. [É.-J.-A. Auclair], Consécration et intronisation de sa grandeur Mgr Ant. Racine, premier évêque de Sherbrooke . . . (Sherbrooke, 1874). Jacques Desgrandchamps, Monseigneur Antoine Racine et les religieuses enseignantes, 1874–1893 (Sherbrooke, 1980). Germain Lavallée, “Monseigneur Antoine Racine et la question universitaire canadienne (1875–1892)” (thèse de ma, univ. de Sherbrooke, 1954). [J.-A. Lefebvre], Monseigneur Antoine Racine, premier évêque de Sherbrooke . . . (Sherbrooke, 1894). J.-G. Lavallée, “Monseigneur Antoine Racine, premier évêque de Sherbrooke (1874–1893),” CCHA Sessions d’études, 33 (1966): 31–39.

Cite This Article

Jean-Guy Lavallée, “RACINE, ANTOINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/racine_antoine_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/racine_antoine_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Guy Lavallée |

| Title of Article: | RACINE, ANTOINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | September 4, 2024 |