Source: Link

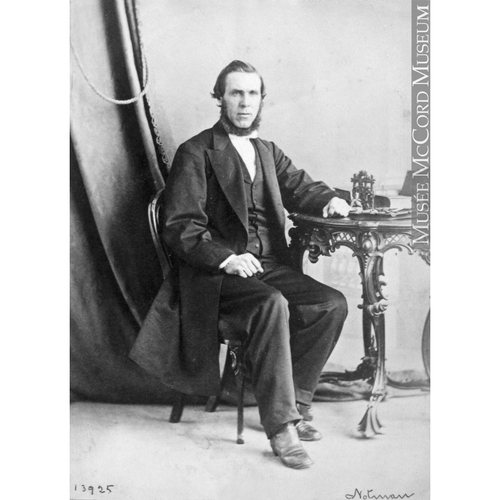

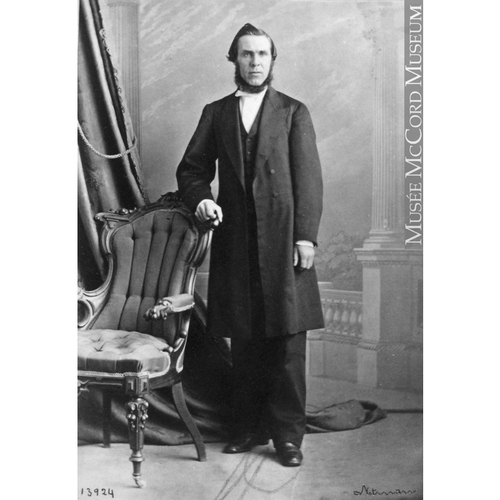

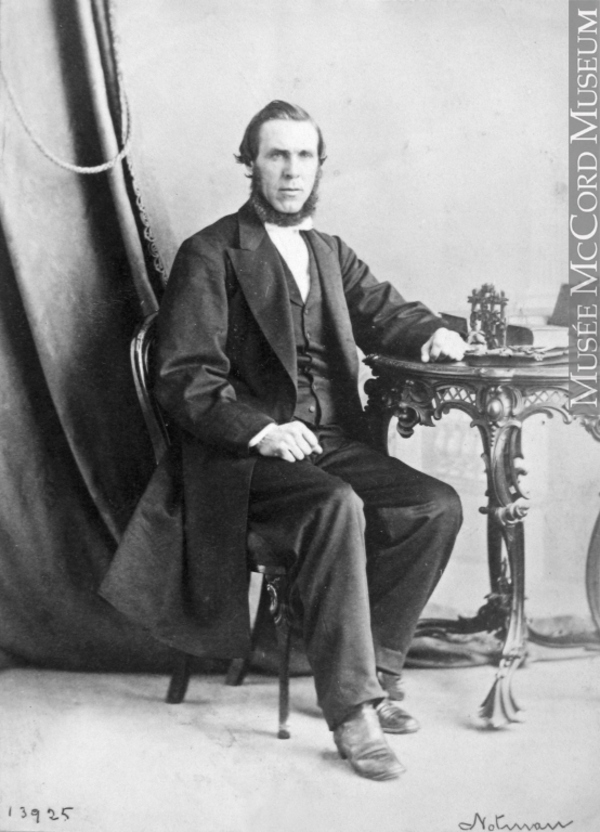

KING, JOHN MARK, Presbyterian minister, educator, and author; b. 26 May 1829 in Yetholm, Scotland, one of four children of Ralph King and Mary Scott; m. 4 Dec. 1873 Janet Mcpherson Skinner in Toronto, and they had two children; d. 5 March 1899 in Winnipeg.

John Mark King received an ma from the University of Edinburgh in 1854, and studied theology at the United Presbyterian Divinity Hall in Edinburgh, as well as at the University of Halle, where he came under the influence of such spiritually intense theologians as Friedrich August Gottreu Tholuck and Julius Miller. His Scottish religious heritage, which combined a warm, evangelical piety and a firmly structured theological thought (reaching back to Ebenezer Erskine and finding its culminating expression in Thomas Chalmers), received another attractive articulation in the teachings of Tholuck and Müller. This evangelical tradition, with its centre of gravity in the doctrines of sin, grace, and regeneration, decisively shaped King’s life and thought.

In 1856 King came to Upper Canada as a missionary of the United Presbyterian Church. After a year in the back settlements, he was ordained on 27 Oct. 1857 and became minister of the rural charge of Columbus (Oshawa) and Brooklin (Whitby). In 1863 he was called to the Gould Street United Presbyterian Church, Toronto; in 1878 its congregation built and moved to the more spacious St James Square Presbyterian Church. For 20 years King exercised an influential ministry in this prominent congregation, which included such public figures as Oliver Mowat*, William Caven*, principal of Knox College, and George Brown* of the Globe. The congregation became widely known for its vigorous leadership in the cause of home missions. Its church was also known as the College Church because of the large number of Knox students who attended King’s special Bible classes. A strong supporter of the college, King served on its board of management and senate, and chaired its board of examiners for many years. The place King came to occupy in the Presbyterian Church was indicated in 1882 when Knox selected him to be the first person upon whom it conferred an honorary dd, and in the following year when he was elected moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Canada.

In response to a request from the presbytery of Manitoba, the General Assembly of 1883 appointed King the first principal and professor of theology of Manitoba College. A difficult situation confronted him. The college, which had moved to Winnipeg from Kildonan in 1874, had undertaken the construction of new buildings during a period of inflation and had incurred a debt of $40,000; in 1883 Winnipeg was experiencing a severe financial depression. Upon his arrival King took firm control of the college’s affairs and he quickly won the confidence of everyone, especially the business community. Discussing his abilities as a financial administrator, lawyer Colin H. Campbell* wrote, “As a rule we do not look for skilled financiers in profound theologians and gifted preachers.” But, he added, “any country would have been honored to have [King] as finance minister, or any large financial institution as manager.” He raised money throughout eastern Canada and Britain as well as locally, and he handled it carefully, supervising in detail all aspects of the college’s finances, including student boarding and tuition fees and even the purchase of coal, wood, and furniture. The college’s debt was soon wiped out and King went on to repair and enlarge the buildings at a cost of $45,000, all of which was paid off during his time in office. In addition to putting the college on a sound financial basis, he also set high academic standards, proved himself to be a splendid teacher, and demonstrated a quality of leadership that called forth the best in faculty and students alike, thus leading the college into what has been called its “golden period.” He brought distinguished lecturers from Scotland and invited the public to hear them; he also gave three series of well-attended public lectures to the women of Winnipeg. In such ways he enhanced the place the college occupied in the community.

The 1880s were also years of deep personal sorrow for King. In 1886 his wife died and about a year and a half later his nine-year-old son died suddenly from scarlet fever. To honour his son he gave a scholarship in theology, and to perpetuate his wife’s memory he donated to the college a rose-window on the subject of theology designed by British artist Henry Holiday; it is now in the University of Winnipeg. King’s widowed sister took charge of his household and helped him raise his daughter, Helen Skinner, who would marry Charles William Gordon*, better known as author Ralph Connor.

As western Canada opened up to settlement, the needs of the churches in the west became particularly acute. To enable students to fill pulpits during the winter, a summer theological session was begun at the college in 1893. Thenceforth King taught 11 months of the year. Besides handling the administrative affairs of the college and carrying a heavy teaching load in both arts and theology, he preached widely in Winnipeg and throughout the province, and exercised leadership in the courts of the Presbyterian Church. He also kept up with the theological debates of the day, over such matters as biblical criticism, liberal theology, the Social Gospel, and the understanding of human nature and history. King entered the fray and took clear and firm positions.

Both his writings on controversial religious issues and his preaching were shaped by a concern that the truth of the Christian faith should be delineated in “relation to the permanent and universal needs of man.” His deepest conviction, and the one integrating his thought, was that it was precisely the great doctrines concerning the incarnation, the atonement, and the work of the Holy Spirit which met man’s deep and universal needs. From this perspective, he was critical of the “new theology” because it played down or obscured these doctrines, which he saw as alone adequate “to the full strain of human need.” He constantly urged theological students to pay close attention to theology and to preach the great doctrines, not as pieces of an abstract system of thought but in the most intimate relation to the universal need for meaning, consolation, and regeneration.

Two books – A critical study of “In memoriam”, a series of public lectures on Lord Tennyson’s poem, and The theology of Christ’s teaching, a set of class lectures published posthumously – provide insight into King’s thought, but he gave particularly forceful expression to his views in public lectures delivered each year at the opening of the classes in theology. In these lectures, some of which were published, he addressed both his own concerns and the controversies of the age.

The lecture of 1890, published as Three great preachers and dealing with Alexandre-Rodolphe Vinet, Henry Parry Liddon, and John Henry Newman, reveals some of the intellectual and spiritual qualities King most admired and sought to develop in his students. Newman’s power lay in his “profound spiritual insight,” combined with his “clearness, precision and simplicity” of expression. The distinguishing feature of Liddon’s preaching was the prominence he gave to great doctrines. In Vinet he found a spirit “at once philosophic and devout” whose sermons exhibited a rare “union of intellectual and moral excellence” and related the Christian message to man’s enduring needs. In 1893 in a thoughtful lecture entitled “The spirit in which theological enquiry should be prosecuted,” King confronted the increasing polarization taking place in theological circles. The atonement, published in 1895, acknowledges that there have been valid reasons for a shift away from the doctrines towards a more ethical, humanitarian emphasis but stresses that an understanding of Christianity which does not have the doctrine of atonement at its centre goes against the “whole drift and tenor” of scriptural teaching, fails “to supply any adequate reason for the Incarnation,” and proceeds on “a radically defective” view of the human condition. King returned to a similar issue in 1897 in The purely ethical Gospel, examined. Ethical concerns were important to King and he acknowledges in this work that positive gains have been made in recent years in obtaining a clearer recognition of the ethical dimensions of Christianity. Nevertheless, he argues that the purely ethical Christianity which has acquired such popularity “is seriously and painfully defective, if it does not indeed change the centre altogether, and thus throw even the truths which it retains out of their proper relations.” In addressing some of the hotly debated theological issues of the day King was conservative, standing in “the old paths,” but he was not narrow. He was familiar with modern liberal theological thought and was open to its strengths but he clearly saw its weaknesses.

King also discussed issues of a more secular character, both local and national in scope. In 1889 he turned to the question of religion in Manitoba schools [see Thomas Greenway*] in a lecture, Education: not secular nor sectarian, but religious. A purely secular education, he asserts, “proceeds upon a radical misapprehension of the constitution of man’s being, in which the intellectual and moral nature are inseparably intertwined.” He opposes, however, the idea of “separate” or “sectarian” schools in which “the distinctive doctrines and rites” of one church would be taught. He does not consider the “differences between the Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches, small or unimportant” but is convinced that the “great common beliefs of Christendom” could form the content of the type of religious education needed in public schools.

King exercised a profound influence on the religious and educational life of Manitoba during the 1880s and 1890s. He united firm convictions and clarity of thought with a warm and open spirit, thus inspiring confidence, love, and respect. He had a genius for friendship. The combination of learning and practical wisdom made him an unusually effective leader, whose opinions and support carried great weight. When he died, there was not only the expected outpouring of grief but also an extraordinary expression of a sense of loss to the church and to the nation. Joseph Walter Sparling, principal of Wesley College, spoke for many when he said, “No death has occurred in Manitoba since I came to it ten years ago that has, in my judgment, made so great a vacancy.”

John Mark King is the author of numerous books, articles, addresses, and sermons, some of the most important of which are The atonement . . . (Winnipeg, 1895); The characteristics of Scottish religious life and their causes . . . (Toronto, 1882); A critical study of “In memoriam” (Toronto, 1898); Education: not secular nor sectarian, but religious (Winnipeg, 1889); The purely ethical Gospel, examined . . . (Winnipeg, 1897); “The spirit in which theological enquiry should be prosecuted,” Manitoba College Journal (Winnipeg), 8 (1893): 127–34; The theology of Christ’s teaching (Toronto, 1903); and Three great preachers (Vinet, Liddon and Newman) . . . (Winnipeg, 1890).

GRO (Edinburgh), Yetholm, reg. of births and baptisms, 6 July 1831. Ont., Office of the Registrar General (Toronto), Marriages, registration no.1873-05-014331. Private arch., Ruth Gordon (Winnipeg), J. M. King, letters, sermons, and note-books. UCC, Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario Conference Arch. (Winnipeg), J. M. King papers; Manitoba College, Board, minutes, 6 Jan. 1882–30 Sept. 1924; Senate, minutes, 1897–1937; Presbyterian Church in Canada, Manitoba Presbytery, minutes, 1875–84; Synod of Manitoba and the North-West Territories, records, 1884–99; Winnipeg Presbytery, minutes, 1897–1913; records, 1884–97. UCC-C, J. M. King papers. Univ. of Winnipeg Arch., J. M. King papers. Manitoba College Journal, memorial number [1899]. PCC Acts and proc., 1883. Manitoba Morning Free Press, 6, 7, 9, 13 March 1899. Winnipeg Daily Tribune, 7 March 1899. A catalogue of the graduates in the faculties of art, divinity and law, of the University of Edinburgh, since its foundation (Edinburgh, 1858). Gordon Harland, “John Mark King: first principal of Manitoba College,” Prairie spirit: perspectives on the heritage of the United Church of Canada in the west, ed. D. L. Butcher et al. (Winnipeg, 1985), 171–83. Schofield, Story of Man., 2: 612–19. [T. W. Taylor], Historical sketch of Saint James Square Presbyterian congregation, Toronto, 1853–1903 (Toronto, n.d.). C. W. Gordon, “The Rev. J. M. King, D.D., first principal, Manitoba College,” Manitoba College Journal, 23 (1907): 1–6.

Cite This Article

Gordon Harland, “KING, JOHN MARK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/king_john_mark_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/king_john_mark_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon Harland |

| Title of Article: | KING, JOHN MARK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |