Source: Link

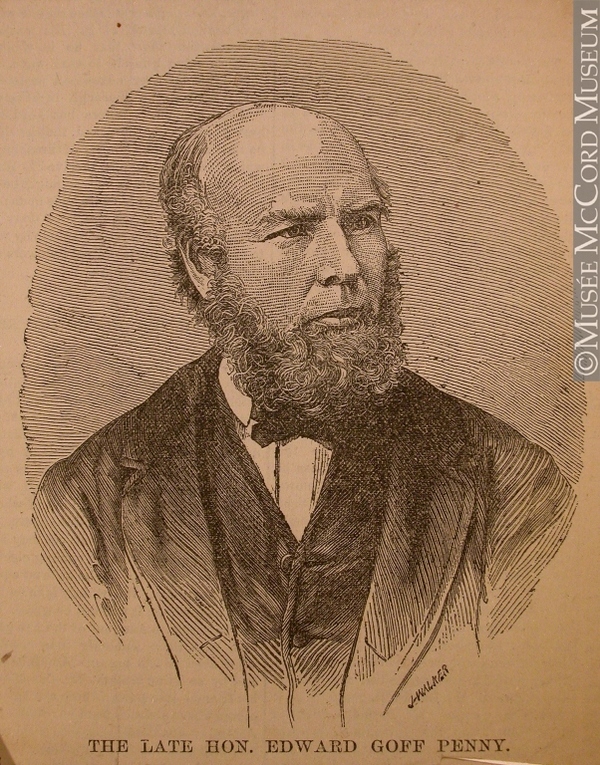

PENNY, EDWARD GOFF, journalist, businessman, and politician; b. 15 May 1820 in Islington (now part of London), England, son of John Penny and Emmiley May; m. 13 Oct. 1857 at Montreal, Canada East, Eleanor Elizabeth Finley, née Smith, and they had one son, Edward Goff; d. 11 Oct. 1881 at Montreal.

Edward Goff Penny’s father was a middle class London coal merchant of liberal views. Penny evidently received a practical education, perhaps in the working place as well as at institutions of formal learning, for along with a lively intelligence and writing ability he had a knowledge of shorthand. In 1844 he immigrated to Montreal, where his training earned him a position as cub reporter with the Montreal Herald. Since his employment was conditional upon learning French, Penny lived for six months with a family in Longueuil and acquired a reasonable facility in speaking the language. He served initially as a court reporter, to which practice he introduced shorthand techniques, and later became the Herald’s political correspondent while the legislature sat in Montreal from 1844 to 1849. At the same time he studied law and in 1850 was admitted to the Lower Canadian bar, though he never practised law as a profession.

Since the beginning of the 1840s the Herald had been widely accepted as Montreal’s leading commercial newspaper, but its political reputation was less even. Memories of the rebellions of 1837–38, the debate over the act of union in 1841, and the violently Tory stance taken by the Herald’s previous editors, Adam Thom and James Moir Ferres*, were still vivid when Penny arrived in 1844. Robert Weir Jr, the paper’s editor since 1838, had died in 1843 and David Kinnear* had taken over as editor-in-chief the following year. Under his direction the Herald began to acquire a reputation as a moderately conservative, though independent, journal. Penny later claimed that, as a newcomer untouched by existing national antipathies, he had had an influence in moderating the Herald’s stridently Tory tone. With Kinnear as the major shareholder, a group consisting of Penny, Andrew Wilson, the business manager, James Potts, the printer, and James Stewart, the commercial editor, in 1846 purchased the Herald from the heirs of Robert Weir Sr.

The new owners’ claim to moderation was severely tested, however, during Montreal’s convulsive reaction in 1849 to the Rebellion Losses Bill introduced by the Reform ministry of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and Robert Baldwin* and the consequent agitation for annexation. The Herald avoided the belligerent posturing and attacks on French Canada which marked most of Montreal’s English language press over the period. By early July, however, the Herald was suggesting the peaceful annexation of Canada to the United States to offset the economic dislocation imposed by the advent of British free trade. Penny not only signed the Annexation Manifesto of October 1849, as did most of the Herald’s proprietors, but he was also the paid assistant secretary of the Montreal Annexation Association until its demise in 1850.

The Herald emerged from the crucible of 1849 an adherent of the Liberal or Rouge party forming in Canada East, a political position which Penny evidently found personally attractive. Easily the finest writer on the paper, he succeeded David Kinnear as editor-in-chief when the latter retired some time in the period 1856–57. By 7 Jan. 1863, a little over a month following Kinnear’s death, Penny and Andrew Wilson had assumed control of the paper, and by March 1865 were its sole proprietors. While extending the Herald’s highly regarded coverage of Montreal’s commercial affairs, Penny remained a firm supporter of the opposition Rouges and, in particular, the editorial champion of those English-speaking liberals clustered about Luther Hamilton Holton*, a political and personal friend. By the confederation era, Henry James Morgan* regarded Penny as “undoubtedly the ablest journalist connected with the Rouge, or Liberal, press.”

Two events in particular served to set Penny apart from most of his fellow journalists: his attack upon the confederation scheme and his support of the Union during the American Civil War. Genuinely respecting American institutions, Penny dismissed the Southern cause as “vain and foolish” treason, and slavery as “the vilest, most gigantic, and once most widely spread crime of Christendom.” He tried consistently to restrain Canadian anxieties over the potential Northern threat to Canada and viewed the more bombastic pro-Southern sentiments emanating from certain sections of the Conservative party as “insane.” The “isolation and antagonism” he experienced as a result of his position surpassed the bitterness of any other political battle. Penny later recalled the Civil War years as “the winter of my career as a journalist.”

From its beginnings in 1864, Penny considered the confederation scheme as, at best, a “timid expedient.” It avoided the central issue of proportional representation as demanded by Reformers in Canada West, and erected an expensive, vaguely defined federal system which potentially left Protestants in Canada East at the mercy of the far more populous French Canadians. He felt that “both English and French in Lower Canada . . . would be better off under the old union, with a fair addition to the Upper Canadian share of the representation.” In a pamphlet published in January 1867, an uneven collection of arguments aimed directly at London, Penny claimed that the Colonial Office had already injured the principle of responsible government by its unconstitutional interference in favour of the confederation scheme. The imperial parliament should refuse to interfere further by rejecting the confederation legislation then before it. A subsequent anonymous pamphlet dismissed Penny as part of “a small rump of a quasi-annexation party in Canada,” a charge echoed in the Montreal Gazette. Once the legislation had been passed, however, Penny requested Herald readers to give the new system a fair trial. Yet as late as 1873 Penny privately referred to George Brown*, the Reform leader and instigator of the confederation coalition, as a hypocritical opportunist who had “sold out to the enemy.”

Although Penny at times was given to sulking, even threatening at the height of the Pacific Scandal in 1873 to take his journal out of the Liberal alliance after Brown’s Globe had slighted him, he was highly regarded within Liberal party circles. Apart from his appointment in 1863 as a justice of the peace by the ministry of John Sandfield Macdonald* and Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, he received few public honours from the party. On 13 March 1874, however, after the victory of the Liberals under Alexander Mackenzie*, he was appointed to the Senate for the Alma division of Quebec and in May 1875 was chosen a Canadian commissioner to the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition of 1876.

Penny’s Herald steadfastly supported Mackenzie’s “sound and honest” government from 1874 through the election campaign of 1878. The Herald first greeted Sir John A. Macdonald*’s National Policy platform as a cynical bluff, but later as dangerous, “mischievous quackery.” While attracted to free trade ideas, Penny recognized the problems that their implementation held for Canada beside an increasingly protectionist United States. Still he believed in a “natural current of affairs” in world trade and resisted government manipulation of the economy. He accepted the electoral verdict but believed that the protectionist policies would develop “like the fabled Dead Sea apples, which contained nothing but ashes within the beautiful rind.”

Penny spoke not only as a newspaperman but also as a successful businessman. A director of the Montreal Telegraph Company, he was also, according to the Montreal Gazette, “a large shareholder and director of several leading public institutions.” Penny had amassed by his death in 1881 a “fair fortune for a gentleman.” In an obituary, the Montreal Star, reflecting the genuine regard in which other journalists held him, claimed that “as a political editor, Mr. Penny had no superior in the Dominion”; as if to prove this assertion, the prestigious Montreal Herald began to decline after his death.

Edward Goff Penny was the author of The proposed British North American confederation; why it should not be imposed upon the colonies by imperial legislation (Montreal, 1867). A reply to the pamphlet also appeared: The proposed B.N.A. confederation; a reply to Mr. Penny’s reasons why it should not be imposed upon the colonies by imperial legislation (Montreal, 1867).

ANQ-Q, AP-G-203. AP, St Stephens Anglican Church (Montreal), Register of baptisms, marriages, and burials, 13 Oct. 1857. PAC, MG 24, B40, 8; MG 26, B; MG 27, I, E13. “The Annexation movement, 1849–50,” ed. A. G. Penny, CHR, 5 (1924): 236–61. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1879, 10, no.152: 1–12. Canada Gazette, 1 Aug. 1863, 21 March 1874. Elgin–Grey papers (Doughty), I: 75–76; IV: 1492–94. Gazette (Montreal), 3 Feb. 1844, 9 March 1874, 12 Oct. 1881. Globe, 12, 14, 15 Oct. 1881. Montreal Daily Witness, 12 Oct. 1881. Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, 7 Jan. 1863; 18 July, 17 Oct., 12 Nov. 1864; 25 Jan., 11, 25 March, 3, 17 April 1865; 19 Jan., 26 March 1867; 20 March 1874; 26 March, 19, 20, 23 Sept., 23 Oct. 1878; 12, 13 Oct. 1881. Beaulieu et J. Hamelin, La presse québécoise, I: 27–28. Dominion annual register, 1880–81. Wallace, Macmillan dict., 589. H. C. Klassen, “L. H. Holton: Montreal businessman and politician, 1817–1867” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1970). Thomson, Alexander Mackenzie.

Cite This Article

Lorne Ste. Croix, “PENNY, EDWARD GOFF,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/penny_edward_goff_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/penny_edward_goff_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lorne Ste. Croix |

| Title of Article: | PENNY, EDWARD GOFF |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |