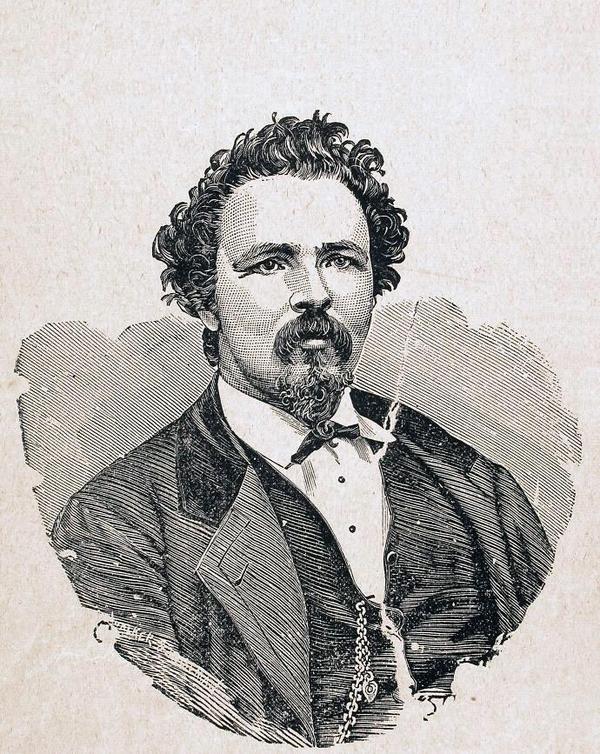

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

McKIERNAN, CHARLES, known as Joe Beef, soldier and innkeeper: b. c. 1835, probably at Virginia, County Cavan (Republic of Ireland); d. 15 Jan. 1889 in Montreal, Que.

Charles McKiernan is believed to have attended the artillery school at Woolwich (now part of London) as a boy, and to have been a quartermaster in the British army during the Crimean War (1854–56). Whenever his regiment was short of food, he had an unrivalled knack of somehow finding meat and provisions, hence his nickname Joe Beef. Although it has proved impossible to determine the date of his coming to America it seems to have been connected with the Trent affair [see Charles Hastings Doyle]. He may have arrived at Halifax in 1861, or at Montreal in 1864; he is believed to have come with the 10th Brigade, Royal Artillery. Joe Beef was in charge of the military canteen on Île Sainte-Hélène in 1864. Four years later he obtained his discharge and opened in Montreal “Joe Beef’s Canteen,” an establishment soon known throughout North America.

Joe Beef chose his site wisely: on Rue Saint-Claude, in the heart of a district teeming with activity. Directly opposite was the Bonsecours market, and within a couple of hundred feet the port, where “carters of cord wood,” bricks, and hay jostled with longshoremen and sailors. There were also factories nearby which employed a large number of workers. In 1875, when Rue Saint-Claude was widened, he was forced to move. But he refused to leave the port district and relocated further west, in a three-storey building on the corner of Rue de la Commune and Rue Callières. Thus he retained his clientele.

From the outset Joe Beef’s inn was different. He did not set out to get rich but rather to make a reasonable profit while extending charity to the destitute. Consequently he always gave food and lodging to the down-and-out. “I never refuse a meal to a poor man,” he told a journalist from La Patrie. “No matter who he is, whether English, French, Irish, Negro, Indian, or what religion he belongs to, he’s sure to get a free meal at my place if he can’t afford to pay for it.” His generosity quickly assured him the friendship of the poor and every day between noon and one p.m. “about 300 longshoremen, beggars, odd-job men and outcasts from Montreal society” came into his premises.

Joe Beef’s richest customers treated themselves to beef with onions, bread, butter, and tea with sugar, all for ten cents. The poorest received a bowl of soup and bread. The quality of the food served seems to have been excellent. According to one journalist, “assurances have been given that one of the largest firms supplying food and drink in the city considered [our] host one of its best clients, from the point of view of both the quality and the quantity of his purchases.” Joe himself claimed that amongst his customers were the biggest eaters on the continent. He required 200 pounds of meat and 300 pounds of bread a day to satisfy this crowd. Some came in so ravenous that they threw themselves on the meat like wild animals and, from 1876 to 1884, there were seven recorded cases of asphyxia, three fatal, caused by eating far too quickly.

At Joe Beef’s, one could also get a bed for the night. On the Rue de la Commune, in the ten second-floor rooms which served as a dormitory, there were more than 100 iron or wooden bunks. The inn closed at 11 p.m., at which time silence became compulsory. Those who chose to sleep there lined up at the bar to put down the ten cents for which they received a blanket. The shaggy ones were shaved by one of Joe’s assistants who acted as “barber,” and the filthiest had to take a bath. “After the bath, Joe sprinkled his boarder’s body with an insecticide preparation, a yellow powder kept in a huge pepper pot.” The clients had to sleep in the nude for “Joe claims it is better to burn more coal than to pay for washing the blankets.”

In the evening an employee of the inn patrolled neighbouring streets looking for anyone in distress. “During the heavy winter storms, it often happens that drunks are found at night lying in a deep snow bank, where they would certainly die if they were not picked up by the night watchman and taken to the dormitory of the hotel. ‘I would be the most unhappy of men,’ Joe says, ‘if the public learned one day that some poor wretch died of hunger or cold at my door.’ In the morning the boarders are awakened at seven and for breakfast receive ‘a Labrador chicken,’ the owner’s term for a herring and a large hunk of brown bread. The floors are swept, then covered with sawdust again, [and] sprinkled with chloride of lime. The windows are opened and ‘the river breeze clears the air in the sleeping quarters.’” Joe did not stint on sanitary measures. In 1884 La Patrie noted that only once in eight years had the Montreal press recorded a death in his house, “whereas not a week passes without some deaths being reported in the almshouse on Dorchester Street, where the unfortunates sleep on the floor and have very meagre fare.”

But how could such an establishment be run at a profit, when salaries had to be paid to some ten employees and board and lodging supplied free to many clients? Joe Beef seems in fact to have taken advantage of his lengthy service in the British army. Thus, as early as 1868 his status as an army veteran had exempted him from the heavy expense of obtaining an innkeeper’s licence. In addition, he managed his business by insisting on the observance of regulations. A client who failed to conform was quickly called to order; if he repeated the offence he was thrown out. But such incidents were rare, for as La Patrie noted, “all the guests in this strange hostelry have the same respect for the owner as the English soldier has for his sergeant.”

In the army Joe Beef had also learned to lay in plenty of stores. To serve 600 meals a day now was no particular problem for him. He had a farm at Longue-Pointe (now part of Montreal), where he raised animals for slaughter. Every day he bought all the bread not sold by Montreal bakers – 300 or 400 pounds – and when it got too stale he fed it to his animals. It was said that the scraps from the tables were devoured by the inhabitants of the strange menagerie (a buffalo, bears, wolves, foxes, and wild cats) he had bought from sailors and kept in the cellar of his inn.

But most of his income came from the sale of alcoholic beverages. In his establishment people drank a lot, but never without paying. According to La Minerve the 480 gallons of beer consumed each week would bring the innkeeper $360 and would represent only half of the drinks sold. When a customer was convicted of drunkenness, Joe often hastened to pay the fine, and temperance advocates were shocked by his conduct. In 1875 John Dougall, the owner of the Montreal Daily Witness, launched a campaign against the inn, denouncing it as “a den of perdition” and “a place of ill fame.” For five years Joe let Dougall carry on, while making fun of him. Then on 20 April 1880 he brought a libel suit against him which made the whole town chuckle and earned Joe the apology he demanded.

The innkeeper was well regarded by the working class. Between 17 and 26 Dec. 1877 he gave the Lachine Canal labourers, who were on strike because of wage cut-backs, 3,000 loaves of bread and 500 gallons of soup. He paid the travel expenses of two delegations which went to Ottawa to present a defence of the workers’ stand to the government. On 21 December 2,000 strikers gathered in front of his establishment to hear him speak. La Minerve the following day noted that he “delivered a facetious address in rhymed endings which was heartily applauded. The innkeeper aired grievances about the manner in which the ‘bourgeois’ treated their employees, and advised the strikers never to resort to violence to uphold their rights.” A week later arbitrators named by both sides reached an agreement putting an end to the strike.

Less than three years later Joe similarly supported the strikers of the Hudon Cotton Mills Company, Hochelaga, giving them 600 loaves of bread on 26 April 1880. But these strikers were less successful than had been those at the Lachine Canal. They demanded a reduction in their workday from 12 to 10 hours, as well as a 15 per cent wage increase, and denounced the brutality of some of their foremen and irregularities in the payment of wages. However, they were forced to return to the job, having gained only a 30-minute reduction in their workday.

Joe also helped the Hôpital Notre-Dame and the Montreal General Hospital. Metal alms-boxes were prominently displayed on the ground floor of the inn asking visitors to make a contribution to support the two establishments. And as the account books show, the innkeeper regularly turned over to the hospitals the sums collected, even contributing to them himself. As well, he encouraged the work of the Salvation Army, which took up public subscriptions for the destitute. At his request, each Sunday members of this charitable organization stationed themselves in front of his inn and sang hymns, for which he gave them money. Moreover, at his death his establishment was taken over by them.

The innkeeper of the Rue de la Commune was a colourful figure with a satirical sense of humour. His business card introduced him as “the Son of the People,” and stated: “He cares not for Pope, Priest, Parson or King William of the Boyne; all Joe wants is the Coin. He trusts in God in summer time to keep him from all harm; when he sees the first frost and snow poor old Joe trusts to the Almighty Dollar and good old maple wood to keep his belly warm, for [of] Churches, Chapels, Ranters, Preachers, Beechers and such stuff Montreal has already got enough.” But he could be tolerant too. In April 1876 he declared to a French reporter: “A preacher can make as many converts as he likes in my canteen, for 10 cents a head. As for me, if I wanted to take the trouble, I could make them fall for any religion you like, just as I can make free thinkers of them. I propose to invite [Charles-Paschal-Télesphore Chiniquy*] to come and preach here when he gets back from the lower provinces.” It is not known if the temperance orator was invited, but John Currie, the pastor of the American Presbyterian Church on nearby Rue Inspecteur, made an impression on Joe Beef; he was allowed to preach to Joe’s clients for seven months before he set off for a tour of the United States. “He is a good man,” the innkeeper had told his regulars, “and he can come and talk to you any time he likes.”

Joe Beef was wed twice. About 1865 he had married Margaret McRae, who died on 26 Sept. 1871. For her funeral he harnessed the oddest animals of his menagerie to lead the procession to Mount Royal Cemetery. As he had retained the post of commissary in the militia, he was able to secure the services of a military brass band, which performed en route the funeral march from Handel’s oratorio Saul. On the way back, at Joe’s request, they played an old military ditty, “The girl I left behind me.” A few months later, on 13 Feb. 1872, at Montreal, he married Mary McRae, his first wife’s sister.

On 15 Jan. 1889 Joe Beef died suddenly of a heart attack, at the age of 54. The Montreal Daily Witness noted: “For twenty-five years he has enjoyed in his own way the reputation of being for Montreal what was in former days known under the pet sobriquet of the wickedest man. His saloon . . . was the resort of the most degraded men. It was the bottom of the pit, a sort of cul de sac where thieves could be corralled. The police declared it valuable to them as a place where these latter could be run down.” But Joe was much more popular than the paper made him out to be. On 18 January his widow and six sons committed him to burial in what La Minerve termed the most impressive funeral held in Montreal since that of Thomas D’Arcy McGee* in 1868. Every office in the business district closed for the afternoon and 50 labour organizations sent representatives. The procession following the ornate hearse drawn by four horses “caparisoned in sombre-hued housings” was said to be several blocks long. “This crowd consisted of Knights of Labor, workers and manual labourers of all classes. All the luckless outcasts to whom the innkeeper-philanthropist had so often extended a helping hand had come forward, eager to pay a last tribute to his memory.” At his death, La Minerve valued his assets at $80,000.

AC, Montréal, État civil, Anglicans, St Thomas (Montreal), 18 Jan. 1889. ANQ-M, État civil, Anglicans, St Thomas (Montreal), 28 Sept. 1871; Méthodistes, East End (Montreal), 13 Feb. 1872. La Minerve, 21, 22, 24 déc. 1877; 19, 20, 24, 26, 27 avril 1880; 16, 17, 19 janv. 1889. La Patrie, 24 mars 1882, 28–30 oct. 1884. Gazette (Montreal), 16 Jan. 1889. Rodolphe Fournier, Lieux et monuments historiques de l’île de Montréal (Saint-Jean [Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu], Qué., 1974), 197. Jean Hamelin et al., Répertoire des grèves dans la province de Québec au XIXe siècle (Montréal, 1970). Montreal directory, 1871–79. E. A. Collard, Montreal yesterdays (Toronto, 1962), 269–81. H. E. MacDermot, A history of the Montreal General Hospital (Montreal, 1950), 35. Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, III: 24. Léon Trépanier, On veut savoir (4v., Montréal, 1960–62), IV: 197–98. Joseph Germano, “L’auberge de Joe Beef,” La Rev. rationale (Montréal), 1 (1895): 634–38. É.-Z. Massicotte, “À Montréal, le long de l’ancien port,” BRH, 43 (1937): 149–51.

Cite This Article

Jean Provencher, “McKIERNAN, CHARLES, known as Joe Beef,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckiernan_charles_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckiernan_charles_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Provencher |

| Title of Article: | McKIERNAN, CHARLES, known as Joe Beef |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |