Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FOX, TERRANCE STANLEY (known as Terry Fox), marathon runner and cancer-research fund-raiser; b. 28 July 1958 in Winnipeg, son of Rolland (Rolly) Murray Fox and Betty Lou Wark; d. 28 June 1981 in New Westminster, B.C.

Terry Fox was the second child of Rolly Fox, a switchman for Canadian National Railways, and his wife, Betty, a part-time worker in a card shop. He grew up with an older brother, Fred, and a younger brother and sister, Darrell and Judith. In the mid 1960s his family moved from Winnipeg to Vancouver, and then to Port Coquitlam, where he would spend the rest of his life. He had a normal childhood as a member of a middle-class, nuclear family, going to school and participating in sports. He was an avid competitor in any sport, but particularly in basketball. According to one of his high-school coaches, Bob McGill, he was not very skilled, at least initially. He was also short for a basketball player; at the beginning of Grade 8 he was only five feet (1.52 metres) tall. Determined to make his high-school team, he practised endlessly and achieved his goal. He remained a member of the team throughout high school.

After graduation Fox entered the kinesiology program at Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, in the autumn of 1976; he hoped to become a physical-education teacher. During his studies he continued to compete in sports, often with his childhood friend Doug Alward, and that fall he was accepted on the varsity basketball team.

On 12 Nov. 1976 Fox was involved in a minor car accident. Except for a bruised knee he emerged unscathed, although his car was completely wrecked. As weeks and then months passed, the pain, instead of subsiding, became more and more difficult to bear. A general practitioner recommended that he consult a specialist, but on 3 March 1977, before his scheduled appointment, his father brought him to the emergency department of a hospital because the throbbing pain was too much to endure.

The result was unexpected. Instead of a torn ligament, which Fox had thought was the problem, the examination revealed a malignant tumour. He was diagnosed with osteogenic sarcoma, a rare type of cancer relatively more likely to develop in young males than in young females. In the late 1970s the treatment was amputation, followed by chemotherapy to ensure that there was no propagation of cancerous cells.

For Fox, the news was “a total shock,” but he did not have much time to dwell on the subject. On 9 March, less than a week after the diagnosis, he underwent surgery. He quickly got used to his crutches and received physiotherapy in order to become accustomed to walking with a prosthetic leg. He progressed well, returning to his studies and taking part in sports soon after his operation.

In the summer of 1977 Fox was contacted by wheelchair athlete Richard Marvin (Rick) Hansen, who asked him to join his wheelchair-basketball team. Hansen had been active in the Canadian Wheelchair Sports Association and encouraged Fox to make good use of his time in a wheelchair. At first Fox hesitated: he knew his competitive nature, and he worried that failure would lead him into deep disappointment. Yet he agreed to attend the tryouts, and made the team. He played in basketball tournaments while receiving chemotherapy, and his team won three national titles. The first time he was ever mentioned in a newspaper was on 7 May 1979 in the Vancouver Sun, where his role in the victory was acknowledged.

The 16 months of chemotherapy at the British Columbia Cancer Control Agency, where Fox had been required to go every three weeks, were more difficult to endure than learning to walk again. Worse, according to him, was his stay in the cancer clinic, an experience that marked him significantly. Although he was given much hope concerning his chances of survival, he saw many young children whose cases were more serious than his and who had little or no chance of recovery.

During his time at the clinic Fox became aware of the plight of cancer victims and the need to find cures for the various forms of the disease. In the 1970s cancer research had already made some great advances, and Fox was told that the survival rate for the type of cancer from which he suffered had increased from 15 per cent in 1974 (two years before his diagnosis) to 50 per cent or more at the time of his treatment. He understood this statement to mean that the more research was undertaken, the closer doctors would come to finding a cure. Yet despite certain progress, funding was scarce and researchers often moved to other fields even though cancer, after heart disease, had been the second leading cause of death in Canada for both men and women since the 1930s.

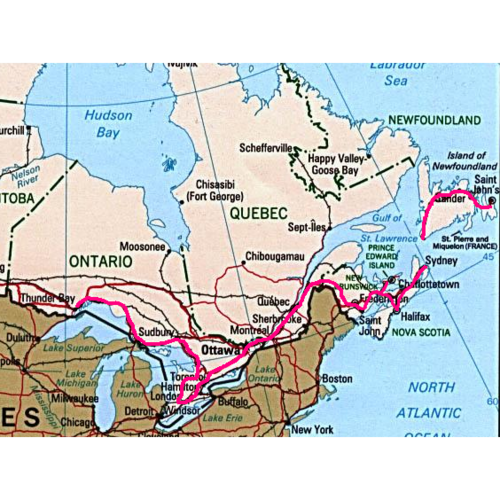

Shortly before the amputation of his leg, one of Fox’s high-school coaches, Terri Fleming, brought him an article from Runner’s World (Mountain View, Calif.) about Dick Traum, who had run in the New York City Marathon on his prosthetic leg. This inspirational story, combined with his difficult experience in the cancer clinic, gave Fox the idea of running across Canada to collect funds for cancer research. In early 1979 he started training on his own, keeping track of his distances and his caloric intake, as well as his university assignments, in a daily journal. For practice he entered the Labour Day Classic, a marathon in Prince George, hoping to cover half of the distance. He finished last, but completed the full course. He continued to train every day and a few weeks later he began to tell his friends and family about his intention of running across Canada. Although his mother initially balked at the proposal, his friend Alward readily agreed to accompany him on the journey. They quickly reached the understanding that Fox would run and Alward would drive, cook, clean, take care of media relations, and make plans for fund-raising. Fox and Alward prepared a tentative itinerary of 8,530 kilometres and Fox, using the imperial system, calculated that by running 30 miles (48 kilometres) per day, he could leave St John’s, Nfld, on 12 April 1980 and arrive in Port Renfrew, B.C., on 10 September, during a period that would allow him to avoid most of the cold weather. He had, however, never achieved more than 37 kilometres per day in his training.

On 15 Oct. 1979 Fox approached the Canadian Cancer Society’s British Columbia and Yukon Division office with a now well-known letter asking for support, in which he declared: “Somewhere, the hurting must stop.” Hesitant at first, the CCS agreed to sponsor him on the conditions that he obtain clearance from his doctor and submit to regular medical check-ups throughout his run. The CCS proposed the name Marathon of Hope and set its sights on collecting $1 million. Fox had also written to other organizations, many of which agreed to help with his project: the War Amputations of Canada offered to replace his prosthesis as needed, the Ford Motor Company of Canada provided a van, the Imperial Oil Company contributed funds for fuel, Canada Safeway sent food vouchers, Adidas Canada furnished running shoes, and Fox and Alward’s airfares to the east coast were covered by Pacific Western Airlines and private donors.

The two young men left British Columbia in early April 1980, settled in St John’s, and continued their preparations. Fox gave a few interviews before the marathon began. During his first television appearance, he was reasonably confident in his ability to achieve his ultimate objective of crossing the entire country on foot: “If I don’t make it, it’s going to be something that nobody would make it.” He started on 12 April 1980 with an official send-off by the mayor, Dorothy Wyatt. A few local journalists reported on his departure.

Fox gradually garnered support for his cause during his run through Newfoundland, which he completed by 6 May, but his reception in the other Atlantic provinces varied considerably from one place to another. The Canadian media was slow to take up his story. Indeed, the launch of the marathon, although mentioned in many newspapers, was mostly buried in the middle pages and not much information was included. The Toronto Star was an exception, assigning a reporter, Leslie Scrivener, who provided weekly reports, almost from the beginning of the marathon. On occasion, people lined up along the side of the road to cheer him on, and some families welcomed both Fox and Alward into their homes, providing meals and a place to shower and sleep, but in other instances Fox would arrive in towns that were wholly unprepared or even unaware of his visit. Since provincial CCS offices could decide whether or not to assist him, the backing was uneven, as he noted in his journal. For example, there were plenty of receptions and related activities and many people encouraged him throughout his run in Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island (24 May to 27 May), and New Brunswick (27 May to 10 June). The successful fund-raising campaign in Channel–Port aux Basques, Nfld, had inspired Fox to increase his expectations for the Marathon of Hope. After the small town of 10,000 managed to gather $10,000, he believed that it was possible to collect at least $1 for each Canadian. However, little was done in Nova Scotia (7 to 24 May) or Quebec (10 to 28 June), because the CCS organizations there had decided not to promote the marathon or at least did not pressure local staff to organize events. Since Fox was running shortly after the society’s own annual fund-raising campaign, some branches did not have the personnel to start yet another solicitation. Furthermore, although it may have been up to the local CSS offices to arrange activities, it had been understood during the planning stages that Alward was responsible for ensuring that the local media was aware of his arrival. Poor attendance at some events created tension between the two young men, both eager for the success of the marathon but lacking experience (and support) in handling public relations and the media.

Besides coping with the varying degrees of enthusiasm throughout the Atlantic provinces, Fox also had to deal with unpredictable spring weather that included high winds and falling snow and caused slippery roads: “It was snowing and miserable, and I had a huge hill to go up,” he noted in his journal on 4 May after he passed through St George’s, Nfld. Added to these challenges were the many physical problems Fox endured: painful blisters, falling toenails, a bleeding and aching stump, and mechanical issues with his artificial leg, which was not made to withstand the stress he was exerting on it. Dizzy spells and occasional difficulty in breathing, which would later be linked to the spread of his osteogenic sarcoma, made his daily run even more of a struggle. In addition, his relationship with Alward remained tense.

The first weeks of the run took a toll on both young men. Living in such close quarters was a trying experience and was compounded by regular arguments over their respective responsibilities. Fox felt at times that Alward was not doing enough in terms of public outreach and the media, while Alward no doubt found it hard to live up to Fox’s expectations. At one point the relationship was so strained that they barely spoke to each other, pushing a wearied Fox to telephone home from Nova Scotia to share his difficult situation. His family came to meet them shortly thereafter, and following a frank discussion between Fox and Alward, the friendship was soon mended. Two weeks later, in Saint John, they were joined by Terry’s younger brother, Darrell, who would continue the marathon with them. The Fox family counted on Darrell’s cheery nature to help prevent new tensions from developing, but such problems were a thing of the past.

Fox was concerned about his journey through Quebec even before his arrival on 10 June, since neither he nor Alward spoke French. There, some people yelled at him from the side of the road, either because he was slowing down traffic or because they thought he was foolishly risking his safety, and not many gathered to cheer him on, which in turn meant that little money was collected. At one point near Drummondville he was required by the local police to change his route; the original itinerary was considered too dangerous because of the increased traffic expected for the provincial holiday of 24 June; the alternative route directly affected the visibility of the run. Fox would later express the belief that if the marathon had received more publicity in Quebec, the province’s residents would have responded enthusiastically, as other Canadians had. “It was very disappointing; it’s not because they’re French and we’re English. Anyone can get cancer,” he noted. The people who did support him were proud to do so. In Montreal he met with and obtained the backing of Isadore Sharp, the owner of the Four Seasons Hotels chain, who pledged $2 per mile and enjoined 999 other Canadian corporations to do likewise.

After being discouraged in Quebec, Fox and Alward remembered their arrival in Ontario more positively. A crowd welcomed Fox as he crossed the border, at Hawkesbury, on 28 June. In fact, he had been asked by the CCS to slow his progress through Quebec to give Ontario regional CCS offices enough time to organize events for him. He arrived in the nation’s capital on 1 July, and performed the opening kick-off at a Canadian Football League exhibition game in Ottawa. On 4 July he met with Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau*, but Trudeau had been poorly briefed, to Fox’s great disappointment. “He didn’t seem to know much about the run.… He didn’t even know I was running for cancer,” he wrote in his journal.

By the time Fox reached Toronto, however, he had become a celebrity, and the media throughout the country started to provide more regular updates on his marathon, reporting at least every two weeks, or weekly as the Toronto Star did. The Toronto visit on 11 July was as successful in raising funds as it was in generating publicity and public awareness. During one event Fox spoke to about 10,000 people in the city’s Nathan Phillips Square. The CCS estimated that $100,000 was collected that day.

Fox achieved celebrity status quite rapidly considering that he had begun his marathon in mid April. The cause for which he ran resonated more and more with Canadians, explaining in part his meteoric rise in popularity after the Toronto event. Fox’s own attributes were fundamental to his success: he was extremely photogenic (young, good looking, and likeable), spoke well, and came across as modest and unassuming. He projected a charismatic persona, which was perfect for attracting media attention.

After Toronto, Fox continued through Ontario and was well received in every town he visited. His popularity sometimes seemed to weigh on him, and he found himself increasingly distracted: “I can’t run a quarter mile without someone coming to talk to me.” The intrusions became such an issue that the CCS provided readers of the Ottawa Citizen with instructions: “He will make appearances during rest periods. Companion runners should be ‘mature’ and must stay at least 10 feet away from him.” In addition, although Fox was thankful for the many fund-raising activities that were now organized in his name everywhere he went, juggling the marathon’s social demands and running on a gruelling schedule taxed him to the limit. Some events forced him to slow down, make significant detours, or halt altogether. Sponsors started to contact him and ask him to endorse their brand names or businesses, which he consistently and vehemently refused to do. For example, in Niagara Falls, he refused to appear at Marineland, an attraction park, because he was not allowed to canvas for funds; he was angered that people wanted to use him for financial gain.

As he became a celebrity, reports began to focus on his personal life rather than the run, a shift that would contribute to his eventually strained relationship with the media. Articles that criticized his fiery temper and his disregard for his health began to emerge, but these were negatively received by the public. Often the CCS would notice an increase in donations after there had been critical coverage. Some stories expressed concern about the message Fox was sending by performing such a difficult and perhaps reckless mission. Others reported on the bleeding of his stump, the heart murmur that had been discovered before his departure and which was not being monitored, or the lack of regular medical check-ups (which had been a requirement of the CCS). Fox usually responded to such comments with: “I know my own body.” Certainly the article that most angered him was one by New Westminster columnist Raymond Douglas Collins, who stated that he had not actually run through Quebec but instead had been driven through the province. A retraction was soon published.

When Fox arrived near Thunder Bay, Ont., he felt weaker than usual and was experiencing frequent dizzy spells. On 1 September, after enduring intense pain in his chest, he asked to see a doctor. Tests determined that the cancer had spread; there was a tumour in each lung. The one in the left lung, the size of a fist, was too close to his heart to be operable. Chemotherapy was the only solution. The following day he announced at a press conference that he had to abandon his marathon for a while, but he vowed to continue as soon as he was able to do so. He returned home to his family and began treatment. He had completed 5,373 kilometres, an average of 42 per day, and had raised $1.7 million. At this point donations started pouring into the CCS. Fox received letters and telegrams of encouragement and support from around the world. Former United States president Gerald Rudolph Ford and Pope John Paul II were among the well-wishers, as were thousands of Canadians. Many newspapers suggested that he had done more for national unity than anyone else, comments greatly influenced by the context of the period, when provincial leaders were finding it difficult to agree on the patriation of the constitution [see René Lévesque; Trudeau]. Fox asked that people not continue his run for him; instead, a five-hour telethon was quickly organized by the CTV Television Network and aired on 9 September. It collected $10 million. On 1 Feb. 1981 Fox achieved his dream of raising one dollar for each Canadian; the country had 24.1 million inhabitants at the time and the Marathon of Hope had brought in $24.7 million.

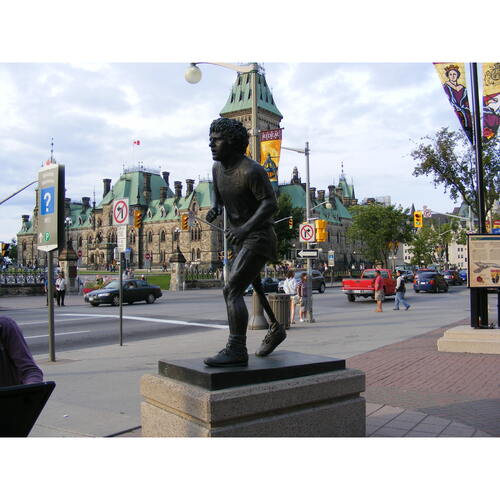

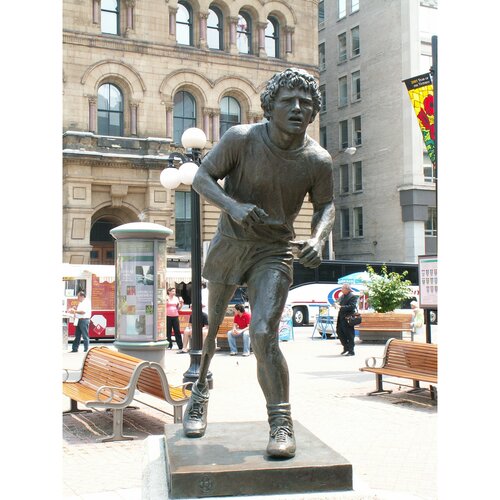

Fox received numerous honours in the period between his diagnosis in Thunder Bay and his death ten months later. On 18 Sept. 1980 he became the youngest person to receive the Order of Canada. Governor General Edward Richard Schreyer travelled to Port Coquitlam for the ceremony. The award is usually presented twice a year on designated dates, but Schreyer and the council who advised him decided that because of Fox’s illness and “his contribution to the country,” an exception should be made. On 21 October he was granted the highest honour in British Columbia, the Order of the Dogwood, by Premier William Richards Bennett; on 22 November the American Cancer Society gave him its Sword of Hope Award; on 18 December his athletic feat was recognized by the Lou Marsh Award, conferred by representatives of the Canadian sports media to the nation’s top athlete of the year; and on 23 December he was voted the Canadian newsmaker of the year by members of Canadian Press Limited. Fox agreed to act as adviser for the script of a movie that was to be produced about him, and he was told that a stamp would be released and a statue raised in his honour near Thunder Bay. During this time, on the suggestion of Isadore Sharp, it was agreed that a run would be organized by the Four Seasons Hotels and the CCS as an annual fund-raising event in locations throughout Canada. The Terry Fox Run would become a tradition that continued into the 21st century.

Fox tried several medications, including the controversial interferon, a drug that had yet to show any positive results in clinical studies, but all treatments failed and he died on 28 June 1981, one month short of his 23rd birthday. His death received worldwide coverage. Flags were flown at half mast, an honour usually reserved for politicians and government leaders. The state funeral that was organized in British Columbia was attended by some 200 guests and televised across the country. Other memorial ceremonies took place elsewhere; Prime Minister Trudeau was present at the one in Ottawa.

The money amassed by the Marathon of Hope was transferred to a special fund at the National Cancer Institute of Canada, the research branch of the CCS, because Fox had specified that the funds collected through his run were to go to research rather than prevention or awareness programs. In 1988 the Fox family broke ties with the CCS and took over management of the fund as well as the annual run. Acting through the Terry Fox Foundation established that year, they successfully reduced administrative costs that they believed had been excessive. Until 2009 the foundation was headed by his mother, Betty, who died two years later. The task of directing the organization was taken over by his younger brother, Darrell; his elder brother, Fred, became responsible for communications, and his sister, Judith, saw to the international aspects of the foundation’s work. By 2010 the Terry Fox Run, held each year in more than 25 countries and 750 places, had collected over $600 million in 29 years.

In addition to the monument near Thunder Bay, where he was obliged to abandon the marathon, there are many other statues of Terry Fox in Canada, notably in St John’s, Ottawa, Vancouver, Prince George, and Victoria, probably making him the Canadian most frequently represented in public sculpture. In addition, an icebreaker, a highway, a mountain, and countless schools, sports facilities, and streets bear his name. On 29 Aug. 1981 he was posthumously inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. In 1999 the Dominion Institute (known as Historica Canada since 2013) and the Council for Canadian Unity asked Canadians to choose their greatest heroes; over 28,000 Canadians voted on a dedicated website and Terry Fox headed the list of nominees. When the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation launched a nationwide survey in 2004 to determine the “Greatest Canadian,” Fox placed second after Thomas Clement (Tommy) Douglas. In 2009 the Dominion Institute asked over 1,000 Canadians to identify the country’s most recognizable icons. Fox’s was the most familiar face: 89 per cent of those who responded were able to identify his picture. The Fox family has worked tirelessly to continue Terry’s mission and thus has ensured that Canadians too young to have seen the Marathon of Hope know who he is and what he represents. Their efforts would all have been in vain, however, had there not been a significant number who wanted to remember Fox and who continue to celebrate what he did.

Terry Fox’s legacy is his own tremendous fund-raising success and his accomplishments for cancer research, an achievement he seems to have wanted more than anything else. Intrinsic to that legacy is the participation of ordinary men, women, and children in annual local runs held in his memory. Thanks to the sums granted through the Fox Foundation there have been considerable advances in the treatment of various cancers, notably the fact that osteogenic sarcoma can now be treated without amputation.

Another part of his legacy relates to the culture of humanitarianism. Not only did he inspire people to become active in raising funds for charity, but he also created an innovative method of doing so. Shortly after his visit to Toronto, similar initiatives were undertaken to help cancer research or other causes. Since then, there have been numerous campaigns that have met with varying degrees of success, though none attracted the support given to the Marathon of Hope. For example, a former hockey player, Sheldon Kennedy, travelled across the country on in-line skates to help finance a camp for abused children, and others participated in a bicycle marathon to assist in locating missing children. Although running, biking, or in-line skating across Canada does not garner the amount of support that Fox’s venture did, the idea that individuals can organize fund-raising projects of such magnitude is owed in many ways to Terry Fox.

The website of the Terry Fox Foundation at www.terryfox.org provides information on the organization’s work as well as biographical information on Terry Fox. It includes photographs, entries from his journal, an account of the Marathon of Hope, and a transcript of the letter he wrote to the Canadian Cancer Soc. requesting support. Some radio and television coverage of the Marathon of Hope, including interviews with Fox, can be found in the CBC Digital Arch. (www.cbc.ca/archives/categories/sports/exploits/exploits.html) and the Arch. de Radio-Canada (archives.radio-canada.ca/sports/exploits). The results of the 1999 poll can be seen at www.historicacanada.ca/sites/default/files/PDF/polls/heroines_heroes_en.pdf and the results of the CBC survey of 2004 are at www.cbc.ca/player/play/1402807530.

Globe and Mail (Toronto), 14 April, 15 Aug., 9 Sept. 1980; 20 April, 3 July 1981. New York Times, 14 Sept. 1980, 3 July 1981. Toronto Star, 14, 22 April 1980; 3 July 1981. Vancouver Sun, 14 April, 21, 29 June, 3, 11 July, 1, 16 Aug., 13 Sept. 1980; 29 June 1981. K. A. Christiuk, “Portrayals of disability in Canadian newspapers: an exploration of Terry Fox” (ma thesis, Univ. of Man., Winnipeg, 2009). S. P. C. Cole, “The legacy of Terry Fox,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston, Ont.), 97 (1990): 253–76. Douglas Coupland, Terry: Terry Fox and his Marathon of Hope (Berkeley, Calif., 2005). A dream as big as our country, directed by John Ritchie, produced by Sharon Kehat and John Ritchie (videorecording, n.p., 1998). Deborah Harrison, “The Terry Fox story and the popular media: a case study in ideology and illness,” Canadian Rev. of Sociology and Anthropology (Toronto), 22 (1985): 496–514. Into the wind, directed by Steve Nash and Ezra Holland, produced by Erin Leyden and Johnson McKelvy (videorecording, Owensboro, Ky, 2010). Running on a dream: the legacy of Terry Fox, directed by Jerry Thompson (videorecording, Vancouver, 2006). Leslie Scrivener, Terry Fox: his story (Toronto, 1981; rev. ed., 2000).

Cite This Article

Julie Perrone, “FOX, TERRANCE STANLEY (Terry Fox),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 21, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fox_terrance_stanley_21E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fox_terrance_stanley_21E.html |

| Author of Article: | Julie Perrone |

| Title of Article: | FOX, TERRANCE STANLEY (Terry Fox) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 21 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |