Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

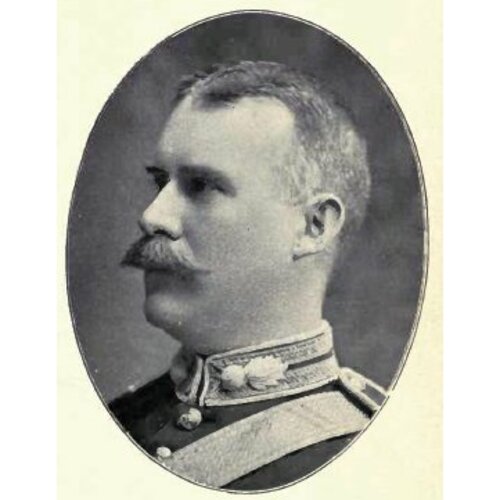

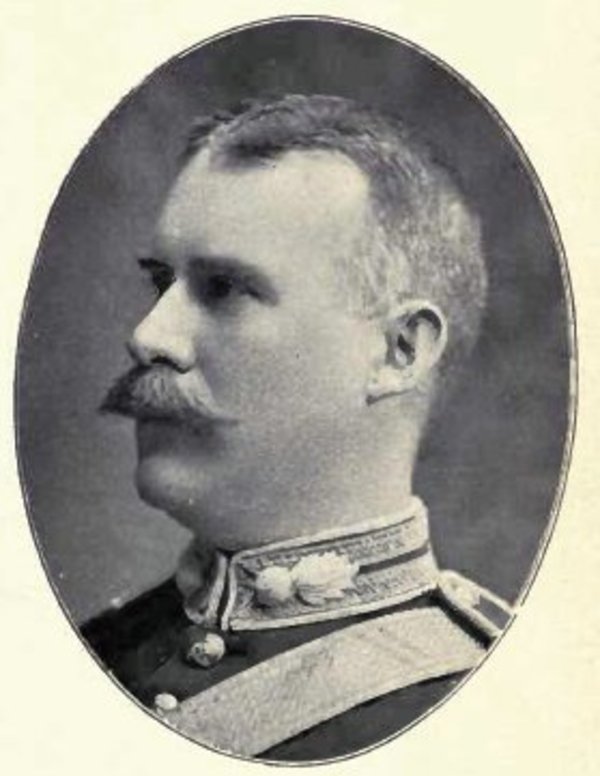

HENDRIE, Sir JOHN STRATHEARN, engineer, businessman, militia officer, politician, and office holder; b. 15 Aug. 1857 in Hamilton, Upper Canada, son of William Hendrie* and Margaret Walker; m. 2 April 1885 Lena Maude Henderson (d. 18 July 1928) in Kingston, Ont., and they had one daughter and two sons; d. 17 July 1923 in Baltimore, Md.

John S. Hendrie attended the Hamilton grammar school and in 1872 he was sent to Upper Canada College in Toronto, where he excelled in mathematics and rugby. On graduation he went to work for the Great Western Railway as a civil engineer. He joined his father and uncle in carting and engineering in the late 1870s, occasionally as a project engineer on lines in Ontario and Michigan. In 1895 he became manager and then vice-president of the Hamilton Bridge Works Company Limited, a reorganization of a firm started by his father to produce bridges, railway turntables, powerhouses, and sheds. By the first decade of the new century, its proficiency in structural steel had led it into the supply of equipment for the electrical power and telecommunications industries. Hendrie, who assumed the presidency after his father’s death in 1906, became known for his “aggressive and skillful” managerial qualities. His business career also included service with the Bank of Hamilton – he became a director in 1903 and president in 1914 – and directorships in Great-West Life Assurance and Mercantile Trust.

His father’s considerable success had made the family one of Hamilton’s wealthiest. Within the city’s civic culture, militia rank was a test of social respectability, and in December 1883 J. S. Hendrie was commissioned a captain in the Hamilton Field Battery. Promoted major in June 1894, he was chosen to command an artillery contingent at the celebration in 1897 of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in England. In September 1903 he was promoted lieutenant-colonel and given command of the 2nd Brigade of Artillery; he would retire in 1909. A president of the Ontario and Canadian artillery associations, in 1907 he was made a commander of the Royal Victorian Order. In addition, he had been a founder of the Hamilton Patriotic Fund in 1899, during the South African War, and served as its chairman from 1906 until it merged with the Canadian Patriotic Fund during World War I. The English Canadian search for national identity in an imperial context was expressed by a keen interest in the War of 1812. Hendrie’s wife was vice-president in 1905 of the Women’s Wentworth Historical Society [see Sara Galbraith Beemer*], which had long advocated the commemoration of the battle site at Stoney Creek. John’s own efforts to create a park there, along with his militia service, led to his appointment to the National Battlefields Commission in 1908.

Meanwhile, Hendrie had entered politics. In December 1900, when Frank E. Walker, the Tory candidate and front runner in Hamilton’s mayoralty race, dropped out, he was approached. Disinclined at first to accept the nomination – his reluctance was genuine, not feigned – he changed his mind, and turned his lack of political experience to advantage in a campaign where the municipal debt was a major issue. His reputation as an efficient businessman was cited by the pro-Tory Hamilton Spectator as his key credential, and Hendrie promised the application of “business methods” to the administration of Hamilton. Elected on 3 Jan. 1901, he cut both its debt and its taxes. The mayor generally served two terms, with an understanding between the Grits and the Tories that an incumbent could seek his second term unopposed. In the 1902 election, however, opposition came from socialist candidate William Barrett, who received a quarter of the votes. Though easily re-elected, Hendrie remained concerned about this support: “a capitalist looking for a place to locate a manufacturing concern will avoid a socialist city every time,” he told the Spectator.

In anticipation of the provincial election on 29 May 1902, Hendrie was nominated as the Tory candidate for Hamilton West in preference to Edward Alexander Colquhoun, the sitting mpp. Hendrie handily defeated Colquhoun (who ran as an independent), Grit candidate Stephen Frederick Washington, and socialist Robert Roadhouse. Though the Liberal government of George William Ross* was returned, the Tories emerged as the party of Ontario’s cities and in 1905 they swept the scandal-plagued Ross government from power. Premier James Pliny Whitney* offered Hendrie the position of minister of public works but he declined, preferring to serve as a minister without portfolio and chairman of the legislature’s railway committee or, as the Toronto Globe put it, “virtually acting Minister of Railways.”

Drawing on the principles of competent management that had earned him his reputation, in March 1906 Hendrie introduced two significant bills on railways and municipal affairs, both of which had engaged the drafting skills of former Conservative leader Sir William Ralph Meredith. The Ontario Railway Act, which regulated all aspects of operations and franchises, including those of a rising number of electric and privately owned lines, helped appease popular sentiment against William Mackenzie’s monopolistic Toronto Railway Company. The second, and related, act formed the semi-judicial Ontario Railway and Municipal Board and gave it unprecedented powers. Within months, under the chairmanship of James Leitch, it had made decisions on a range of issues, among them rates, accidents, strikes, assessments, utilities, and municipal financing. In February 1907 Hendrie continued his regulatory impulse by introducing legislation stripping provincial benefits from any public utility that had secured a federal charter. This aggressive bill drew him into a complex debate over provincial rights and the privileges sought by the Hamilton Radial Electric Railway, backed by a determined John Morison Gibson. The bureaucratic instinct for government by specialistic tribunal that gave rise to the ORMB produced a long list of other agencies, boards, and commissions, which characterized the growth of the administrative state in 20th-century Ontario.

Another major achievement of the first Whitney government, again with a focus on government by expertise and the limitation of private interests, was the establishment in 1906 of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. Hendrie’s part in its development was minor, and his attitude to the public ownership of electrical utilities was ambivalent. In Hamilton he had leaned towards private control; in the legislature he had sat on a select committee in 1903–4 to survey public opinion on the principle of municipal ownership. In 1906 he was appointed to the hydro commission to assuage private interests and to keep a firm hand on the radical populism of its chairman, Adam Beck. Hendrie’s insistence on a critical examination of many early projects was interpreted by Beck as personal animosity rather than a concern for diligence. There was likely an element of both. Hendrie had inherited from his father (and shared with his brothers) a love of horses – his entries won the King’s Plate in 1909 and 1910. Beck too was an avid horseman, and their rivalry at meets and their dramatically different temperaments amplified their persistent conflict at Hydro.

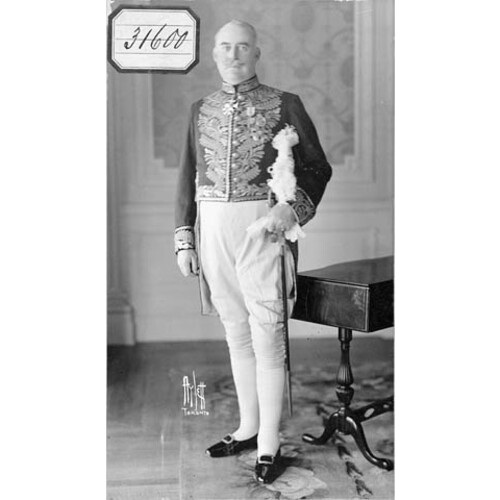

Hendrie was returned in Hamilton West with declining majorities in the elections of 1908, 1911, and 1914. In September 1914 he succeeded his fellow Hamiltonian Sir John M. Gibson as lieutenant governor of Ontario. One reason for his selection was his personal wealth (his father had left an estate worth $2.3 million). His affluence enabled him to maintain a residence in Toronto until the completion there of a new government house, which the Hendries would occupy at the end of 1915. On the announcement of the king’s birthday honours on 3 June 1915, Hendrie was created a kcmg. He frequently used his position to further the war effort. At the opening of the Canadian National Exhibition in August 1915, for instance, he reconfirmed his “life-long” belief in the militia; though he found the term conscription a “misnomer,” he firmly supported “universal training and service for all.” In addition, he continued to be involved in volunteer endeavours such as the Canadian Patriotic Fund, the Speakers’ Patriotic League, and the Hamilton Recruiting League, and he chaired the provincial Organization of Resources Committee, established in 1916 to maximize Ontario’s contribution to the war. In 1917 the University of Toronto recognized his work by awarding him a lld. One of his last functions was a dinner for the Prince of Wales at Government House on 25 Aug. 1919. He retired from public life in November and returned to his Hamilton home, Strathearn, where he would continue to enjoy affiliations with local clubs, the masonic lodge, and the Presbyterian Church.

In July 1923 Hendrie travelled to Baltimore to undergo an operation for intestinal problems at Johns Hopkins Hospital. While recovering, he developed bronchial pneumonia, from which he died on the night of 17 July; his remains were returned to Ontario for burial in Hamilton Cemetery. Survived by his wife and their daughter and son (a war veteran), he left an estate worth almost $1.35 million.

Sir John S. Hendrie’s resolve to bring business methods to government at the local and provincial levels reflected a desire to improve public administration through rigour and expertise. Though a leading industrialist in Hamilton, he was certainly not the most important Canadian of his age; many others were more powerful and more accomplished. His significance lies in his typicality of the urban elite who came of age after confederation. He was committed to an ideology of service that, in the words of historian John English, “created a scale to measure the quality of citizenship.” Measured on this scale, Hendrie did well.

AO, RG 22-205, no.13103; RG 24; RG 80-5-0-133, no.3382. Hamilton Military Museum (Hamilton, Ont.), Hendrie papers. Hamilton Public Library, Special Coll. Dept. (Hamilton), Arch. file, Brown–Hendrie papers. Globe, 28 Sept. 1914. Hamilton Spectator, 8 Jan. 1902. R. M. Bray, “‘Fighting as an ally’: the English-Canadian patriotic response to the Great War,” CHR, 61 (1980): 141–68. R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974). Canadian annual rev., 1901–19. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). J. H. Collinson and Mrs Bertie Smith, The Recruiting League of Hamilton ([Hamilton, 1918?]). Merrill Denison, The people’s power: the history of Ontario Hydro ([Toronto], 1960). DHB, vol.2. John English, The decline of politics: the Conservatives and the party system, 1901–20 (Toronto, 1977). T. H. Ferns, “The life and times of John Strathearn Hendrie, 1857–1923” (graduate research paper, Univ. of Toronto, 1991). C. W. Humphries, “Honest enough to be bold”: the life and times of Sir James Pliny Whitney (Toronto, 1985). J. E. Middleton and Fred Landon, The province of Ontario: a history, 1615–1927 (5v., Toronto, 1927–[28]), 3: 4–6. H. V. Nelles, The politics of development: forests, mines & hydro-electric power in Ontario, 1849–1941 (Toronto, 1974). Ontario and the First World War, 1914–1918; a collection of documents, ed. and intro. B. M. Wilson (Toronto, 1977). W. R. Plewman, Adam Beck and the Ontario Hydro (Toronto, 1947).

Cite This Article

Thomas H. Ferns, “HENDRIE, Sir JOHN STRATHEARN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hendrie_john_strathearn_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hendrie_john_strathearn_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Thomas H. Ferns |

| Title of Article: | HENDRIE, Sir JOHN STRATHEARN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |