As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

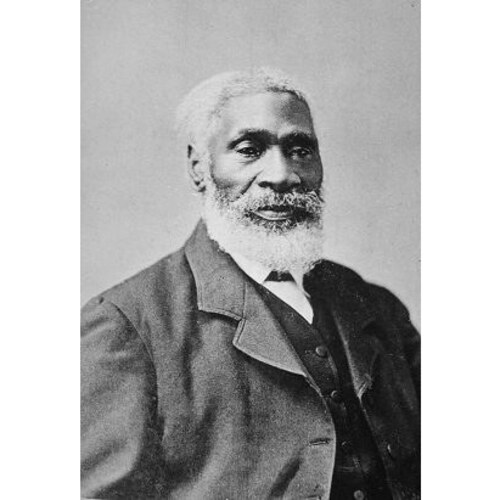

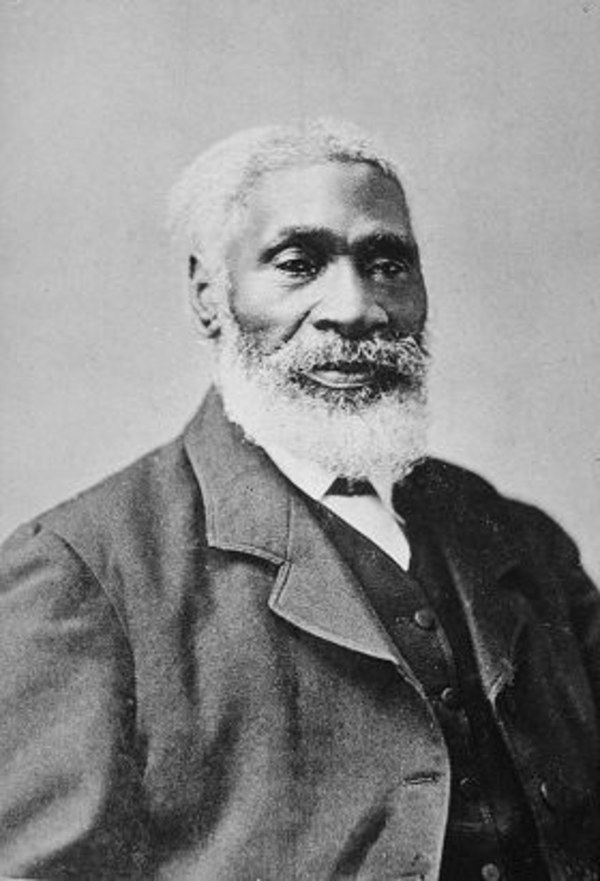

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HENSON, JOSIAH, fugitive slave, Methodist preacher, author, and founder of the settlement at Dawn (near Dresden), Canada West; b. 15 June 1789 in Charles County, Md, to slave parents; m. first c. 1811 Charlotte, a slave (she probably died October 1852), and they had at least 12 children; m. secondly c. 1856 Mrs Nancy Gamble, a free black widow; d. 5 May 1883 at Dresden, Ont.

Josiah Henson was given the Christian name of his first master, Dr Josiah McPherson, and the surname of his master’s uncle. According to his autobiography, the only known source for his early life, Josiah was five when McPherson died and he was sold to less benign masters, first to a tyrant named Robb, and shortly thereafter to Isaac Riley in whose service he was reunited with his mother. As a young man Henson was “maimed for life,” having an arm and both shoulder blades broken by the white overseer of a neighbour of his master. Faithful in his obligations, Henson was a trusted slave, travelling extensively on his master’s business. In 1825, because of financial difficulties, Riley transferred his slaves to the farm of his brother Amos in Kentucky. Henson was charged with the supervision of the journey, and, refusing an opportunity to escape into Ohio, he delivered his charges. At 18 Henson had become a Christian after hearing his first sermon and during his three years in Kentucky he became a Methodist preacher. In September 1828, on the advice of a white Methodist preacher, Henson used a trip to see his master in Maryland as an excuse to tour the country as a preacher and earn money to buy his freedom. In 1829 he arranged the purchase but was betrayed by his master and was taken to New Orleans that same year to be sold. Saved only by the illness of his transporter, his master’s son, which necessitated their return to Kentucky, Henson decided to flee, taking with him his wife and four children. After a long trek through Indiana and Ohio, they sailed to Buffalo whence, crossing the Niagara River, they finally reached Upper Canada on 28 Oct. 1830.

For approximately four years Henson worked as a farm labourer in the Waterloo area where he preached occasionally and began to learn to read. Then in 1834, having planned an exclusively black settlement, he led about a dozen of his associates to Colchester where they rented government land. Shortly after their arrival the group was freed from rent because of a mistake in the conditions of allotment; Henson had planned that they remain only a short time, but after this advantageous happening the settlers remained seven years. Here Henson met Hiram Wilson, the missionary sent by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1836 to minister to Canadian blacks. Aided financially by Wilson’s friend, James Cannings Fuller, a Quaker philanthropist of Skaneateles, N.Y., Henson decided to establish a more formally organized black community for fugitive slaves where they could prove their capacity for freedom. With Wilson and a silent partner (probably Fuller), he purchased 200 acres in Dawn Township, Upper Canada, “for the alone purpose . . . of Education Mental Moral and physical of the Coloured inhabitants of Canada not excluding white persons and Indians”; he also purchased 200 adjoining acres for himself to which he moved his family in 1842. The Canada Mission, a group originally composed of Wilson’s friends in Ohio and later of philanthropists in upstate New York, provided continuing support.

Central to Dawn, as a living and working community, was the British-American Institute. Established in 1842 as a manual labour school for students of all ages, it was designed both to train teachers and to provide a general education “upon a full and practical system of discipline, which aims to cultivate the entire being, and elicit the fairest and fullest possible development of the physical, intellectual and moral powers.” Throughout Dawn’s existence, the institute remained its principal focus.

Until 1868 Henson served regularly on the institute’s executive committee, which not only directed the school but oversaw the farms, grist-mill, sawmill, brickyard, and rope-walk which the settlement undertook. Yet he was never the community’s official administrative head, a role always filled by a white man: first Wilson (1842–47), then Samuel H. Davis of the American Baptist Free Mission Society (1850–52), and finally John Scoble*, former secretary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (1852–68). Throughout, however, Henson functioned as patriarch of Dawn and as a spokesman for Canada’s growing black population. In both capacities, he raised funds by tours of the American Midwest, New England, and New York between 1843 and 1847 as well as England in 1849–51 and 1851–52.

Henson was also persistently involved in Dawn’s internal dissensions and consequent investigations of the institute’s effectiveness and financial management. In 1845 William P. Newman was appointed secretary of the executive committee to reorganize the management and he soon charged the committee, Henson included, with maladministration. Although two years later a Negro convention at Drummondville (now part of Niagara Falls, Ont.) cleared Henson of wrongdoing, in 1848 the trustees of the institute condemned the whole executive committee as “unfit” to direct the affairs of the school. Similarly, investigations in Britain in 1849 and 1852 produced equivocal findings which nourished doubts about Henson’s aptitude.

Much of the tension was generated by conflicts between Henson, as spiritual and symbolic leader, and the official administrators. Spreading throughout the community, these dissensions racked Dawn and nearby centres of black settlement. They caused the resignation of Wilson in 1847, the failure of an attempt to rule by committee from 1847 to 1850, and the brevity of Davis’ tenure. Even Scoble, who stayed at Dawn for 16 years, tangled increasingly with Henson over property sales and in subsequent lawsuits Scoble emerged victorious. In 1868, when the institute closed and after Scoble had left Dawn, the assets of the school were used to establish the Wilberforce Educational Institute in nearby Chatham. After this time the settlement died out and Henson, though he stayed on in Dresden until his death, had lost his role as a black leader.

In 1849 Henson had published his autobiography, which underwent numerous editions and modifications during his lifetime. Three years after the first edition appeared, Harriet Elizabeth Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s cabin; or, life among the lowly (2v., Boston and Cleveland, Ohio, 1852) was published. Stowe acknowledged that she had met Henson and read his book; thereafter, Henson was the putative prototype of the fictional “Uncle Tom.” For some years he made lecture tours as the “real life Uncle Tom” and in 1876 he returned to England to raise funds to support himself, his resources having been depleted in his long court battle with Scoble. He also returned to his old slave home in Maryland briefly in 1877–78, but thereafter spent his last years quietly.

Although Josiah Henson had been a participant in abolitionist activity in the United States, his importance in Canadian history lies in his work at Dawn. It was here that he contributed significantly to Canada’s role in the North American anti-slavery crusade.

Josiah Henson’s autobiography was published under the title: An autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (“Uncle Tom”) from 1789 to 1881 . . . , ed. John Lobb (rev. ed., London, Ont., 1881; repr., intro. R. W. Winks, Reading, Mass., 1969).

Amistad Research Center, Dillard Univ. (New Orleans), American Missionary Assoc. papers. Boston Public Library, Anti-slavery coll. Kent County Land Registry (Chatham, Ont.), Records (mfm. at AO). Massachusetts Hist. Soc. (Boston), G. E. Ellis papers, 1846; A. A. Lawrence papers, 1850–51. UWO, Fred Landon papers. Canada Mission, Report (Rochester, N.Y.), 1844. Colonial and Continental Church Soc., Mission to the Coloured Population in Canada, [Report] (London), 1867. Report of the convention of the coloured population, held at Drummondville, Aug., 1847 (Toronto, 1847). Scoble v. Henson (1861–62), 12 U.C.C.P. 65. A side-light on Anglo-American relations, 1839–1858, furnished by the correspondence of Lewis Tappan and others with the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, ed. A. H. Abel and F. J. Klingberg (Lancaster, Pa., 1927). British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter (London), 1841, 1844, 1846, 1851–52, 1856. Liberator (Boston), 1842–43, 1845, 1848, 1851–52, 1858. Massachusetts Abolitionist (Boston), 1841–42. National Anti-Slavery Standard (New York), 1841, 1851. North Star (Rochester), 1846–47, 1849, 1852, 1854. Oberlin Evangelist (Oberlin, Ohio), 1845. Planet (Chatham), 1859, 1861. Provincial Freeman (Windsor, Toronto, and Chatham), 1854–55, 1857. Voice of the Fugitive (Sandwich and Windsor, [Ont.]), 1851–52. DAB. J. L. Beattie, Black Moses: the real Uncle Tom (Toronto, 1957). J. H. Pease and W. H. Pease, Black Utopia: Negro communal experiments in America (Madison, Wis., 1963); Bound with them in chains: a biographical history of the antislavery movement (Westport, Conn., 1972), 115–39. R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (Montreal, 1971).

Cite This Article

William H. Pease and Jane H. Pease, “HENSON, JOSIAH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/henson_josiah_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/henson_josiah_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | William H. Pease and Jane H. Pease |

| Title of Article: | HENSON, JOSIAH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |