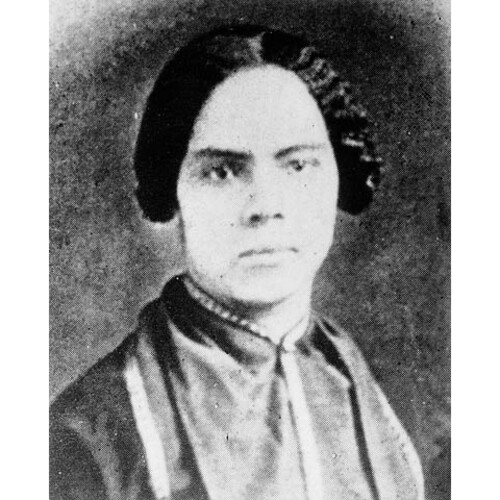

SHADD, MARY ANN CAMBERTON (Cary), educator, abolitionist, author, publisher, and journalist; b. 9 Oct. 1823 in Wilmington, Del., daughter of Abraham Doras Shadd and Harriet Parnell; m. 3 Jan. 1856 Thomas Fauntleroy Cary (d. 1860) in St Catharines, Upper Canada, and they had one son and one daughter; d. 5 June 1893 in Washington, D.C.

The eldest child of a prominent black abolitionist, Mary Ann Camberton Shadd was ten when her family left Wilmington for West Chester, Pa, where she was educated at a Quaker boarding-school. After six years of schooling, the 16-year-old Mary Ann returned to Wilmington, where she organized a school for black youths. From 1839 to 1850 she taught, first at the Wilmington school and subsequently at black schools in New York City, Trenton, N.J., and West Chester and Norristown, Pa, everywhere echoing her father’s view that education, thrift, and hard work were the means by which blacks could achieve racial parity, and thus integration, in America. These views appear in Hints to the colored people of the North, a 12-page pamphlet Mary Ann published in 1849 that pointed to the folly of blacks imitating the conspicuous materialism of whites. In accordance with the legacy of her father’s political activism, Mary Ann implored blacks to take the initiative in anti-slavery reform without waiting for whites to provide beneficence or support. Shadd, only in her mid 20s, had thus gained considerable recognition by articulating what would become her perennial themes: black independence and self-respect.

Shadd’s prominence was truly established, however, when she became a leader and spokesperson for the black refugees who had fled from the United States to Upper Canada after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Believing that she could help these black emigrants, in the fall of 1851 Shadd moved to Windsor, where she opened a school with the support of the American Missionary Association. Although her relations with other black leaders in Canada were initially friendly, she was soon embroiled in a feud with Henry Walton Bibb*. Shadd supported the complete integration of blacks and opposed segregated communities such as those of the Refugee Home Society, with which Bibb was closely connected. She also objected to the society’s “begging” for funds and she went on to question Bibb’s financial gain through his involvement with the society. For his part, Bibb asked in his newspaper, the Voice of the Fugitive, why Shadd had not made her grant from the AMA known to the parents of her pupils. The dispute was injurious to both parties and in January 1853 the AMA, ostensibly because it objected to Shadd’s evangelical religious views, withdrew its support for her school.

Shadd was now writing more extensively. In the summer of 1852 she had published A plea for emigration, a pamphlet in which she sought to encourage American blacks to immigrate to Canada and simultaneously attacked the growing separatist philosophy of Canadian blacks. Despite the widespread circulation of this pamphlet, Shadd desired a continuing medium through which she could disseminate her beliefs. In early 1853, with the timely help of fellow black abolitionist Samuel Ringgold Ward*, Shadd published the first edition of the Provincial Freeman. Proclaimed editor of this bold venture, Ward only lent his name to the newspaper to generate interest and subscriptions. Although Shadd had no official title or position, she nevertheless represented the driving force behind the new enterprise. Staunchly assimilationist in tenor, the first issue appeared in March. Publication was then suspended for a year while Shadd travelled in the United States and Canada on a lecture tour to raise money for her fledgling endeavour.

By March 1854 she had found sufficient support for the Provincial Freeman to resume publication. With the motto “Self-Reliance is the True Road to Independence,” the Freeman, now based in Toronto, began appearing on a regular basis. Shadd used her newspaper to comment on all aspects of black life in Canada, but she focused especially on problems of racial discrimination and segregation. She assailed anyone, blacks and whites alike, who sought to compromise with slavery, and she particularly castigated her fellow blacks who were prepared to accept second-class status. She reserved her greatest vituperation, however, for self-segregated black settlements: to her, these settlements only fostered discrimination, and she urged blacks to seek assimilation into Canadian society. John Scoble* and Josiah Henson* of the Dawn settlement were pilloried almost as exhaustively as Bibb, while grudging approval was granted to the Elgin settlement under William King.

Regular publication of the Freeman was interrupted several times because of financial problems. On 30 June 1855 William P. Newman became editor, though Shadd may well have remained a powerful background force, and the paper was moved to Chatham. In January 1856 Shadd married black businessman Thomas Cary and that May she returned to the Freeman as one of its three editors. After 1856, however, it appeared only sporadically and by 1859, when the financial burden had become too debilitating, publication ceased entirely.

In the wake of the Freeman’s demise, Shadd remained in Chatham and returned to teaching. Yet she watched with great interest as the sectional crisis intensified in the United States. Her hope for the destruction of slavery in the impending conflict had been heightened by John Brown’s arrival in Canada in the spring of 1858. Part of a group that met with Brown, Shadd became privy to the visionary’s intended plans. Another member of the group, Osborne Perry Anderson, a young black, was so taken with Brown that he joined him at Harpers Ferry in October 1859 and survived the raid to record his memoirs in A voice from Harper’s Ferry, edited and prepared for publication by Shadd in 1861.

Through the early years of the Civil War, Shadd continued to teach in an interracial school in Chatham. But she soon grew tired of watching the conflict from a distance. Anxious to assist in the Northern war effort, in late 1863 she accepted an invitation from Martin Robinson Delany to serve as an enlistment recruiter; she returned to the United States to participate in the recruitment programs of several states. Shadd agonized over whether to remain in the United States after Appomattox. She finally concluded that she could best serve her people by remaining to help with the education and assimilation of the millions of newly emancipated blacks. Toward this end, in July 1868 she obtained an American teaching certificate and taught briefly in Detroit before relocating in Washington, D.C. Supporting herself by teaching, she would eventually receive a law degree from Howard University in 1883.

Shadd continued to participate in both civil rights and equal rights movements in the United States, returning to Canada only briefly, in 1881, to organize a suffragist rally. Enfeebled by rheumatism and cancer, she died in the summer of 1893.

Mary Ann Camberton Shadd is the author of Hints to the colored people of the North (Wilmington, Del., 1849) and A plea for emigration: or, notes of Canada West, in its moral, social, and political aspect . . . for the information of colored emigrants (Detroit, 1852). Her edition of Osborne Perry Anderson’s memoirs was published in Boston in 1861 as A voice from Harper’s Ferry: a narrative of events at Harper’s Ferry; with incidents prior and subsequent to its capture by Captain Brown and his men.

Amistad Research Center Library, Tulane Univ. (New Orleans), American Missionary Assoc. Arch., Mary Shadd Cary papers; Canadian files, 1846–78, Mary Shadd Cary papers (mfm. at AO). AO, MS 483 (mfm.). Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Library, Howard Univ. (Washington), ms Division, M. A. Shadd Cary papers. NA, MG 24, K22. Raleigh Township Centennial Museum (North Buxton, Ont.), Shadd family records. Jim Bearden and L. J. Butler, Shadd: the life and times of Mary Shadd Cary (Toronto, 1977). J. H. Silverman, “Mary Ann Shadd and the search for equality,” Black leaders of the nineteenth century, ed. August Meier and Leon Litwack (Urbana, Ill., 1988), 87–100; Unwelcome guests: Canada West’s response to American fugitive slaves, 1800–1865 (Millwood, N.Y., 1985). R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (London and New Haven, Conn., 1971). H. B. Hancock, “Mary Ann Shadd: negro editor, educator, and lawyer,” Del. Hist. (Wilmington), 15 (April 1973): 187–94. A. L. Murray, “The Provincial Freeman: a new source for the history of the negro in Canada,” OH, 51 (1959): 25–31.

Cite This Article

Jason H. Silverman, “SHADD, MARY ANN CAMBERTON (Cary),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shadd_mary_ann_camberton_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shadd_mary_ann_camberton_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jason H. Silverman |

| Title of Article: | SHADD, MARY ANN CAMBERTON (Cary) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |