Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

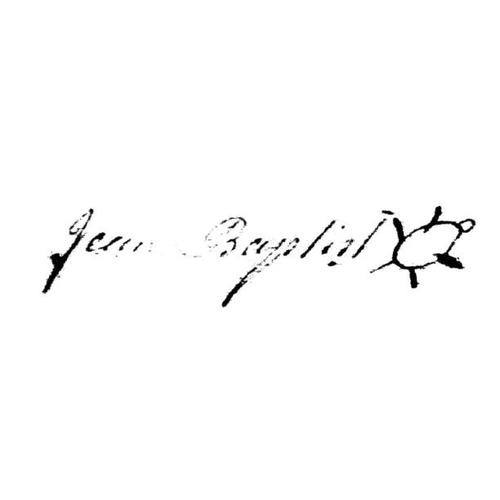

COPE (Cop, Copt, Coptk), JEAN-BAPTISTE, also sometimes called Major Cope, chief of a Micmac tribe of Shubenacadie (N.S.); d. between 1758 and 1760, probably at Miramichi (N.B.).

Jean-Baptiste Cope was involved, along with some of his family, in the Anglo-Micmac war of 1749–53. Following the erroneous statement of the Chevalier de Johnstone*, a number of historians have believed that it was Cope who on 15 Oct. 1750 (n.s.) murdered Edward How on the Missaguash River, or they have confused him with How’s real murderer, Étienne Bâtard, alleging that these two names referred to the same person. It may, at most, be presumed that Cope, an Indian chief living at Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre*’s mission, took part in the ambush organized by Bâtard in the autumn of 1750, when all the Micmacs of Acadia were gathered around Fort Beauséjour (near Sackville, N.B.).

On 14 Sept. 1752 Cope appeared at Halifax to open peace negotiations with Governor Peregrine Thomas Hopson. On 22 November a treaty was actually signed between the English and Cope, along with delegates from his tribe, on the principles of the treaty that had been negotiated at Boston in 1725 with Sauguaaram and other Penobscot chiefs. The news of the agreement with the Micmacs immediately reached Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), and the governor, Jean-Louis de Raymond*, wrote to the minister of Marine on 24 Nov. 1752 that Cope was “a drunkard and a bad lot”; the governor reassured himself with the allegation that the other Micmacs had “disowned” Cope. On 12 May 1753 Raymond returned to the subject, this time calling Cope “a bad Micmac whose conduct has always been uncertain and suspect to both nations.”

Raymond did not know how right he was. Indeed, at the time he was writing the treaty was already broken. In February 1753 an attack on a group of Micmacs by two English soldiers, James Grace and John Conner, had incited Cope to undertake an expedition to avenge his people. On 16 May 1753 he sent his son Joseph to Halifax to ask for a boat and an escort, supposedly to take provisions there. Captain Bannerman was sent, accompanied by seven men, one of whom was Anthony Casteel, to whom we owe the account of this expedition. On 19 May the crew was cut to pieces except for Casteel, who, knowing French, passed himself off for a Frenchman. Cope’s expedition then continued in the direction of Cobequid (near Truro, N.S.), Baie-Verte (N.B.), and finally Louisbourg, where Casteel was freed on 28 June.

By examining the multiple incidents of this trip we can discover the real reasons behind the expedition. Cope wanted to reassert his prestige with his warriors: on 20 May he made a speech along these lines. He also wanted to terrorize his prisoner: on 22 May Casteel was freed from a woman who wanted to torture him, but the woman, together with Cope’s daughter, “danced until froth, the size of one’s fist, came out of their mouths, which caused tears to gush from his eyes.” Cope was, however, above all intent on proving his loyalty to the French: on 23 May he burned the peace treaty which had been signed the previous year, and on 25 May he made a new speech in which he evoked Grace’s and Conner’s horrible crime and stated “that he was surprised to see that the English were the first to begin” hostilities. The peace signed by Cope had thus not lasted six months; the following summer the provincial secretary, William Cotterell, did not hesitate to write that it was Cope himself who had broken it.

According to Johnstone, Cope was in the neighbourhood of Miramichi after the fall of Louisbourg in 1758. This claim seems probable in view of the fact that many Micmacs, Acadians, missionaries, and soldiers took refuge south of the Baie des Chaleurs after the French defeat in Acadia. It is likely, therefore, that Cope died in this region before 1760, since his name does not appear on any of the peace treaties signed between the Micmacs and the English after that date.

AN, Col., B, 89, f.10; 90, f.52; 97, ff.21–22, 30–31; C11A 93, ff.169–72; 97, ff.16–34; C11B, 28, ff.40, 75, 381–87; 29, ff.63, 130f.; 30, ff.110, 113, 117, 189–91; 31, ff.62, 116, 132–35; 32, ff.163, 280f.; 33, ff.22–23, 159–62, 181–83, 197. PAC, MG 11, Nova Scotia B, 4, pp.58, 62, 106; 5, pp.69, 112–20, 139, 152, 162, 164, 178, 234; 6, pp.118, 137, 141, 183f., 254f. [Anthony Casteel], “Anthony Casteel’s journal,” Coll. doc. inédits Canada et Amérique, II (1889), III–26. Derniers fours de l’Acadie (Du Boscq de Beaumont), 72. N.S. Archives, I, 195, 671–74, 682–86, 694–98. PAC Report, 1894, 150, 195, 197f., 202; Report, 1905, II, pt.iii, 281–356. Casgrain, Un pèlerinage au pays d’Évangéline, app.I; Une seconde Acadie, 231. Murdoch, History of Nova-Scotia, II, 193, 211, 213, 219–22. Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (1884), I, 106. Richard, Acadie (D’Arles), II, 85–121, 151–69. R. O. MacFarlane, “British Indian policy in Nova Scotia to 1760,” CHR, XIX (1938), 154–67.

Cite This Article

Micheline D. Johnson, “COPE (Cop, Copt, Coptk), JEAN-BAPTISTE (Major Cope),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 9, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cope_jean_baptiste_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cope_jean_baptiste_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Micheline D. Johnson |

| Title of Article: | COPE (Cop, Copt, Coptk), JEAN-BAPTISTE (Major Cope) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1974 |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | January 9, 2025 |