Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ALEXANDER, WILLIAM, Earl of Stirling, remembered in the land of his birth as a scholar, poet, courtier, and the favourite of James I and Charles I of England in their dealings with Scotland; and on this side of the Atlantic as the putative founder of a new Scotland under the aegis of both monarchs; b. c. 1577; d. 1640. Though his colonizing interest is the chief concern of cisatlantic readers, it cannot be understood without reference to his poetical works, which brought him first to royal notice and subsequently to royal favour and collaboration.

William Alexander was born in the village of Menstrie. He received a thorough classical education in the grammar school of Stirling, under Dr. Thomas Buchanan, nephew of George Buchanan, tutor of James VI of Scotland; and probably attended the University of Glasgow. He made “the grand tour” (France, Spain, Italy, and Holland) at the end of the century, as the companion of his kinsman, the seventh Earl of Argyll, who later introduced him to court.

Before going to court in London he had made some reputation as a poet, with his Tragedie of Darius, published at Edinburgh in 1603 and dedicated to James VI. This was reprinted in London in 1604, together with another tragedy, Croesus. Both reflect his classical education and foreshadow the main character of his poetical works. (Aurora, a sonnet sequence published in the same year, was obviously an earlier work; and A Paraenesis to the Prince was obviously a bid for royal favour.) These were followed in 1605 by The Alexandrean Tragedy; and in 1607 by a collected edition of his tragedies, including Julius Caesar, written in the interval. In this edition the author is described as a gentleman of the Prince’s Privy Chamber.

In this year, 1607, he was granted the rights to the mines and minerals in the barony of Menstrie; and he shared equally with his father-in-law an annuity of £200. (He had married in 1601 Janet, daughter of Sir William Erskine, a relative of the Earl of Mar, who in due course bore him ten children, seven sons and three daughters; and while he was climbing the ladder of fame Providence concealed from him the fact that a grandchild eight years of age was to enjoy for a few months only the heritage of an empty title by primogeniture.) In 1608, he and a relative were made agents for collecting debts due the Crown in Scotland from 1547 to 1588, on a 50 per cent basis; he was knighted in 1609.

In 1612 he wrote An Elegie on the Death of Prince Henrie and was appointed gentleman usher in the household of Prince Charles. Two years later, he published Doomes-Day, or, The Great day of the Lords Judgement, his last poetical work of importance. He had already won on his previous works and, from this date, would continue to win the warm praise of contemporary writers, above all that of Drummond of Hawthornden. Moreover, he had been chosen by King James as collaborator in translating The Psalms of King David.

It was, therefore, as a well-known literary figure, having close associations with both England and Scotland, that he was appointed in 1614 master of requests for Scotland – whose chief duty was to ward off needy Scots from the English court – and, in 1615, a member of the Scottish Privy Council, the highest advisory authority on Scottish affairs. It was in these two positions that he was most intimately associated with King James and, having won his complete confidence, was enabled to obtain his ardent support for his colonial adventures.

During his residence at court, though as a poet Sir William still maintained the futility of human ambition, nonetheless he mingled with those who were promoting the expansion of England overseas, became aware of Scotland’s lack of any part in it, and, as a patriotic Scot, began to dream of making a name for himself by diverting the constant stream of Scottish manhood from the continental wars into a colony that should bear the name of Scotland.

He first approached Capt. John Mason, governor of Newfoundland, 1615–21, and author of A briefe discourse of the New-found-land for aid in getting room for a plantation there. Through Mason’s influence he obtained a grant of the northwestern part of that island, from the Bay of Placentia to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but, although he named it Alexandria, he made no use of it, because of a grander vision that emerged from the suggestion of Governor Mason that he consult Ferdinando Gorges, treasurer of the recently formed Council of New England. (In 1620 the London and Plymouth companies, which in 1606 were granted the territory between latitudes 34° and 45°N under the name of Virginia, were reorganized and the northern part, extended to 48°, was granted to the Council of New England.)

Acting on Mason’s advice, Alexander persuaded King James that the only way to get Scots to emigrate was to give them a new Scotland comparable to New France and New England; and the king conveyed the royal wish to the Council of New England and obtained from the latter the surrender of all their territory north of the Sainte-Croix. Thereupon the king immediately instructed the Scottish Privy Council to prepare a grant of this territory for Sir William Alexander. The grant was signed on 10 Sept. 1621 (o.s.), making Sir William, on paper at least, lord proprietor of what are now known as the three Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé peninsula – to be called for all time New Scotland or Nova Scotia.

Unfortunately, this grant included the territory that had been claimed and nominally occupied by the French as Acadia. The much neglected Charles de Biencourt and a little band of Frenchmen and their Indian allies were the unofficial representatives of French claims in the entire area; this same band under Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour was to play an important role in the later revival of French claims and in the final failure of Sir William’s colonizing projects. Meanwhile in the six years during which his title was practically unchallenged, notwithstanding the continued favour of King James and his son Charles, Alexander was unable to plant permanently a single colonist in his far-flung domain.

This is perhaps not a matter of surprise when one considers his previous lack of experience with practical affairs, the difficulty of combining the roles of a dreamer and a man of action, and the magnitude of the task which he had undertaken single-handed; for he alone had to remould the Scottish national outlook and create a favourable public opinion, whereas the promoters of Virginia, New England, and Newfoundland were numerous and had the English nation behind them.

Though Sir William lacked experience he did not lack either courage or tenacity. In 1622 he hired a ship in London and sent it to Kirkcudbright to pick up settlers and supplies; but it was delayed by the reluctance of artisans to enlist and the scarcity of supplies, encountered bad weather near Cape Breton, left the colonists in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and returned to London for more supplies. In 1623 he sent out another ship to pick up the colonists, but this party found that some of them had died, that others were out fishing, and that too few remained to found a colony. However, ten of these decided to go along with the ship to locate a fit site for a future settlement. They explored as far as Cap Nègre, landed at Port-Joli and Port-au-Mouton, formed a favourable opinion of the natural beauty and resources of the country, but returned to Newfoundland, whence they took passage to England with some of the West Country fishermen, leaving the ship to get its own load of fish. The remainder of the original party apparently became absorbed into the population of Newfoundland.

The net gain of Sir William’s first venture, at an alleged cost of £6,000, was a rather vague but flowery description of New Scotland, which he embodied in his pamphlet An encouragement to colonies, published in 1624 and accompanied by a map on which he sprinkled a number of Scottish names. Thus the Sainte-Croix becomes the Tweed; the Saint John, the Clyde; and the whole is divided into two provinces Alexandria and Caledonia.

In this pamphlet he traces colonization from Abraham through the Greeks and Romans to the Spanish, French, and British, recounts the experience of his first venture, paints a glowing picture of its advantages to gentry and commoner, merchant and missionary, and concludes with an appeal to the king to further the project by making it appear a work of his own and thereby encouraging public “helps, such as hath beene had in other parts, for the like cause” – an obvious reference to the help given by the king to the plantation of Ulster, by the creation of knight-baronets, which brought £225,000 to the royal exchequer.

In response to this appeal, King James informed the Privy Council of Scotland that he had decided to confer the dignity of knight-baronet upon any worthy Scot who would undertake to furnish a number of settlers in return for a portion of New Scotland and instructed the council to prepare a proclamation to that effect. This they did on 30 Nov. 1624, offering a barony and the title of knight-baronet in return for setting forth six men fully armed, clothed, and provisioned for two years, within a year and a day after accepting the honour, at the cost of 2,000 merks and 1,000 merks to Sir William for resigning his interest in the barony. As there was no response to this offer, on 23 March 1624/25 the king wrote the council offering the baronies for a cash payment of 3,000 merks to Sir William, who would use the 2,000 merks for furnishing the settlers. Four days later, King James died without having seen a baronet created or a colonist set forth; but his death did not mean the withdrawal of royal favour: Charles I was equally well disposed to Sir William’s project and for the next five years did everything in his power to induce the Scottish nobility and gentry to support it. By the end of May 1625 he had created eight baronets on the cash basis, with land three miles wide and six long, and on 12 July he renewed the charter of 1621 with additional provisions for a total of 150 baronets and for the incorporation of Nova Scotia into the kingdom of Scotland, in order that Sir William and the baronets could take seisin of their distant lands in the castle of Edinburgh without the necessity of going to Nova Scotia.

Despite the promising beginning, the response to the new charter was very disappointing. There was opposition on the part of the lesser barons to the special privileges offered to the knight-baronets. To meet this Charles demoted the secretary of state for Scotland, who had approved the protest of the lesser barons, and appointed Sir William in his stead. But by 25 July 1626 only 28 baronets had been created and, even if Sir William had received the full sum of 3,000 merks for each, he would have had only £4,666 13s. 4d. to finance his projected colony, considerably less than the £6,000 that he had already expended on the first attempt, for which he had a warrant from King James, still unpaid.

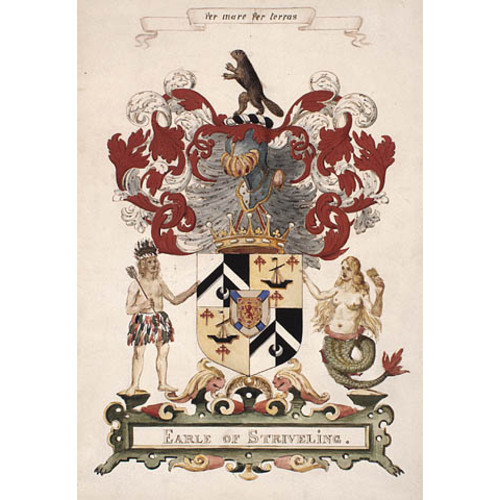

Accordingly, on 25 July 1626 King Charles authorized a committee of the council to meet frequently at stated times to see that the petitioners for the dignity of knight-baronet had satisfied Alexander and that he was prepared to surrender the lands specified, and to award the dignity forthwith. In the same commission the king awarded armorial bearings to the province. (It is from this commission that Nova Scotia derives its flag and present coat of arms.)

As only one baronet had responded by 3 March 1626/27, Charles wrote the council again to speed up matters and stated that unless the full number of baronets were created Sir William would be utterly undone, as he had already spent more on the two ships he was preparing than he had received.

The story of later creations may be summarized thus. Despite repeated urgings only 14 came forward in 1627, 21 in 1628, 7 in 1629, and even after the special badge was offered (27 Nov. 1629), 11 in 1630, and 4 in 1631. That is, 85 baronies only had been disposed of from 1625 to 1631 when Sir William was ordered to give up his colony at Port-Royal to the French and the creation of knight-baronets had degenerated into a scheme of raising money by the sale of titles. In fact 25 baronets were created between 1633 and 1637 after Port-Royal had been surrendered.

Until 1627, Sir William had to contend only with the problems of finance and the reluctance of the Scots to emigrate. But in the spring of that year he had to meet the competition of the powerful Compagnie des Cent-Associés, which Cardinal Richelieu had organized in Paris to control the destinies of New France and to challenge Sir William’s claims to Nova Scotia. The outbreak of war between France and England also brought new adventurers into the field, notably the Kirke brothers, whose brilliant achievements now threatened to supplant Alexander for the time being in the public eye. In 1628, after threatening Quebec, the Kirkes captured the supply ships of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France near Gaspé, brought Claude de Saint-Étienne de La Tour, who was returning to Acadia after seeking help for the French against the British, a prisoner to England, and applied to the king for a grant of the monopoly of trade in Canada, under the Crown of England.

Meantime in February 1627/28 Sir William, whose eldest son, William, was already in command of an expedition towards New Scotland, had induced the king to direct that all prize money collected in Scotland should be turned over to him and to grant him the lordship of Canada – an area of 50 leagues on each side of the St. Lawrence from its mouth to the mythical South Sea. He opposed the application of the Kirke brothers and, supported by the Privy Council of Scotland, obtained a compromise whereby the rival interests were united and agreed to operate under the crowns of England and Scotland. Accordingly, on 4 Feb. 1628/29 a commission was issued to Sir William Alexander the younger and others for a monopoly of the trade of the St. Lawrence, with power to confiscate the goods and ships of any interlopers, to make prizes of all French or Spanish ships, and to displant the French (Royal letters, 47).

It was under this commission that the Kirkes took the fort and trading post of Quebec and brought Champlain and other Frenchmen prisoners to England. It was under the same commission that Sir William the younger helped Sir James Stewart, Lord Ochiltree, to plant a short-lived colony at Baleine in Cape Breton – it was uprooted two months later by Charles Daniel – and that under the guidance of Claude de La Tour he planted a colony at Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal, N.S.), which had a precarious existence until 1632.

The younger Sir William decided to remain in Port-Royal over the winter of 1629–30 and to send home his ships for supplies and reinforcement and Claude de La Tour with a draft agreement for his father to sign, whereby Claude and his son Charles were to receive a large barony (from Yarmouth to Lunenberg) in exchange for their allegiance and assistance. He also sent home the Indian chief Segipt and his wife and son to do homage to King Charles.

During the winter of 1629–30 Sir William managed to get together supplies and reinforcements for his colony, confirmed the agreement with Claude de La Tour, who married a Scottish lady, made him a knight-baronet, and sent him back in May with a patent for his son Charles. However, his own son, returning in the autumn of 1630, had to report that 30 of the 70 colonists had died during the winter, that Charles de La Tour had refused to accept the title of knight-baronet, and that Claude de La Tour had therefore lost face with both those whom he brought and the original settlers at Port-Royal. He in turn found his father deep in a struggle to resist the surrender of Nova Scotia to France in accordance with the Treaty of Susa, 23 April 1629, by which the British and French had agreed on mutual restoration of all territory and shipping taken subsequent to that date. Negotiations dragged on for two years. The British admitted that Quebec had been taken since that treaty but maintained that Port-Royal had been settled in unoccupied territory to which they had good title by discovery, strengthened by the charter of Virginia, the conquest of Argall, the charters of 1621 and 1625, and the homage of the Indian chief. The French insisted that both Quebec and Port-Royal be restored to their original condition or the possessor would have an unfair advantage in negotiation. Finally, King Charles, in dire financial straits, at outs with his Parliament, and lured by the prospect of receiving the half of his wife’s dowry still unpaid by the French, agreed to instruct Sir William to withdraw his colonists with their effects and to destroy the fort and other habitations.

Though these instructions were drafted in 1631, they were not given to the French for submission to the colonists at Port-Royal until a year later, owing to the king’s insistence that the marriage portion must first be paid to his banker. They sounded the death knell of Sir William’s colonizing efforts (notwithstanding his later association with the Council of New England) and his hope of solvency, for by the end of 1632 the colony had been withdrawn and the king’s warrant for £10,000 in compensation for his losses had been dishonoured. The monopoly of minting copper coins in Scotland, given at the time, failed to restore his finances. He died so heavily in debt that his creditors surrounded his death-bed in London, and denied him a peaceful burial in the church of Stirling.

He had enjoyed royal favour to the end so far as the bestowal of titles was concerned (Viscount Stirling, Lord Alexander of Tullibody, 1630; Earl of Stirling, 1633; and Earl of Dovan [Devon], 1639), but this favour did not extend to saving his colony when put in the balance with the queen’s marriage portion. On the other hand his close association with Charles in his attempt to foist episcopacy upon Scotland cost him the affection of many Scots who were neither his debtors nor his creditors.

As to his chief colonial venture, although two centuries were to elapse before unassisted Scottish emigration made New Scotland a reality, it cannot be regarded as a complete failure so long as the name Nova Scotia survives, and its citizens treasure their armorial achievement and their flag.

Champlain, Works (Biggar), VI, 50, 210. [Sir William Alexander], The Earl of Stirling’s register of royal letters, relative to the affairs of Scotland and Nova Scotia from 1615 to 1635, ed. C. Rogers (2v., Edinburgh, 1885). Mémoires des commissaires, II, 193–276 et passim, and Memorials of the English and French commissaries, I, 38–43, 114, 141–44, 552–68 et passim. PAC Report, 1884, Note D, lx–lxii; 1912, 21–53. PRO, CSP, Col., 1574–1660. Royal letters, charters, and tracts (Laing). DNB. G. P. Insh, Scottish colonial schemes, 1620–1686 (Glasgow, 1922). Henry Kirke, The first English conquest of Canada (2d ed.; London, 1908). McGrail, Alexander (argues that the settlement of Port-Royal occurred in 1628, rather than 1629).

Cite This Article

D. C. Harvey, “ALEXANDER, WILLIAM, Earl of Stirling,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/alexander_william_1577_1640_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/alexander_william_1577_1640_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | D. C. Harvey |

| Title of Article: | ALEXANDER, WILLIAM, Earl of Stirling |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |