Source: Link

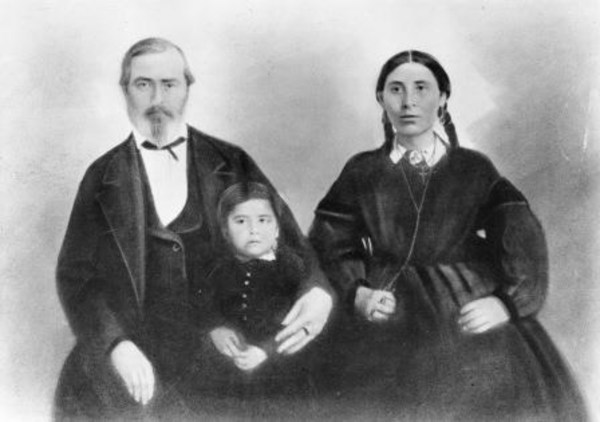

NATAWISTA (Natoyist-siksina, Natawista Iksana, known as Medicine Snake Woman), Blood Indian and peacemaker; b. c. 1824 probably in what is now southern Alberta, daughter of Stoó-kya-tosi (Two Suns), who was sometimes known as Sun Old Man and Father of Many Children; d. March 1893 at Stand Off (Alta).

The daughter of a leading chief of the Blood tribe of Blackfoot Indians, Natawista was wed according to Indian custom to Alexander Culbertson, chief trader for the Upper Missouri Outfit of the American Fur Company, in the early 1840s. Because of the intense competition between American and British traders for the Blackfoot trade, it was common for officers to marry the daughters of chiefs to cement trading relations. In 1843 naturalist John James Audubon met Natawista at Fort Union (Fort Union Trading Post, N.Dak.) on the upper Missouri River and referred to her as an “Indian princess . . . possessed of strength and grace in a marked degree.” Eight years later Swiss artist Rudolf Friedrich Kurz described her as “one of the most beautiful Indian women. . . . She would be an excellent model for a Venus.”

During these years Natawista’s brother Peenaquim* became the leading chief of the Bloods and gained considerable influence within the Blackfoot nation through his relationship with Culbertson. Natawista travelled frequently to the Blood camps and cultivated friendly relations between the Indians and American traders. In 1854 she insisted on accompanying a party of United States government negotiators led by her husband to the Blackfoot camps. “I am afraid that they and the whites will not understand each other,” she said, “but if I go, I may be able to explain things to them, and soothe them if they should be irritated. I know there is great danger.” Partly as a result of her efforts, a treaty was signed a year later. The Blackfeet agreed to live in peace with other tribes, to remain within designated hunting-grounds, and to allow white settlers and military personnel to settle in their region in exchange for the United States government’s promise of annuity payments and other assistance.

In 1858, having made a considerable fortune in the upper Missouri fur trade, Culbertson purchased an estate and show farm named Locust Grove, near Peoria, Ill., and on 9 Sept. 1859 the Culbertsons formalized their frontier marriage there with a Catholic service. During their years together they had five children. Natawista’s life in Illinois was unconventional at times. “When autumn came,” recalled a relative, “she would have a teepee set up on the lawn, take off her white woman’s clothes, don the blanket garb of the squaw and spend the Indian summer in her teepee.” She travelled frequently to the upper Missouri with her husband but fitted equally well into life at Locust Grove.

By 1868 Culbertson’s wealth was gone. The couple moved to Fort Benton (Mont.) so he could resume trading, but some time after 1870 Natawista went to the Blood camps and never returned to her husband. She lived with her nephew Red Crow [Mékaisto], and then became one of the Indian wives of Henry Alfred Kanouse, an American whisky trader from Peoria operating on the Bow River (Alta). In 1874 they were on the Oldman River when the North-West Mounted Police built Fort Macleod (Alta) near by. NWMP surgeon Richard Barrington Nevitt saw her in 1875 and expressed amazement at seeing an Indian woman wearing a “Dolly Varden style” dress and balmoral petticoat over beaded leggings and moccasins.

In 1877 Natawista accepted treaty status in Canada as a Blood Indian under the name of “Natoas-Kix-in, Mrs. H. A. Kanouse,” but by 1880 she had left her husband and was living with Red Crow on the newly established Blood Indian Reserve (Alta). She was described by Winnipeg journalist George Henry Ham in 1885 as “a neatly-dressed squaw, attired after the custom of some white ladies,” who nevertheless preferred “the wild freedom of the plains to the conventionalities of society.” At the time of her death in 1893, Natawista was living on the Blood reserve with Red Crow’s son Nina-Kisoom (Chief Moon).

Arch. of the Diocese of Peoria (Peoria, Ill.), St Mary’s Church, reg. of marriages, 9 Sept. 1859. Mont. Hist. Soc. (Helena), L. H. Morgan, “Journal of Lewis H. Morgan, 1862.” NA, RG 10, B8, 9412, Treaty paylists, Blood bands of Treaty 7, 1877, entry 37. [J. J.] Audubon, Audubon and his journals, ed. M. R. Audubon (2v., London, 1897; repr. New York, 1960), 2. R. F. Kurz, “Journal of Rudolph Friederich Kurz . . . 1846–1852,” ed. J. N. B. Hewitt, trans. Myrtis Jarrell, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bull. (Washington), 115 (1937): 224. R. B. Nevitt, A winter at Fort Macleod, ed. H. A. Dempsey ([Calgary], 1974). Daily Manitoban (Winnipeg), 30 Sept. 1885. H. M. Chittenden, The American fur trade of the far west . . . (2v., New York, 1902; repr. Santa Fe, N.Mex., 1954), 1. Myrtle Clifford, “Three women of frontier Montana” (ma thesis, State Univ. of Mont., Bozeman, 1932). J. W. Schultz, Signposts of adventure: Glacier National Park as the Indians know it (Boston and New York, 1926). “Mrs Alexander Culbertson,” Mont., Hist. Soc., Contributions (Helena), 10 (1940): 243–46. M. W. Schemm, “The major’s lady: Natawista,” Montana (Helena), 2 (1952), no.1: 5–15.

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “NATAWISTA (Natoyist-siksina, Natawista Iksana) (Medicine Snake Woman),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/natawista_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/natawista_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | NATAWISTA (Natoyist-siksina, Natawista Iksana) (Medicine Snake Woman) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |