Source: Link

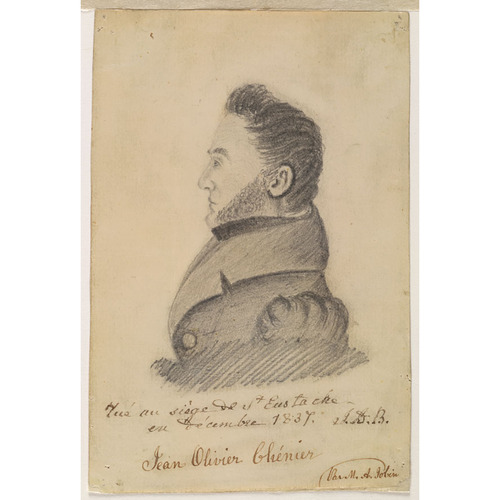

CHÉNIER, JEAN-OLIVIER, physician and Patriote; b. 9 Dec. 1806, probably in Lachine, Lower Canada, or possibly in Montreal, and baptized the following day in Montreal, son of Victor Chénier and Cécile Morel; d. 14 Dec. 1837 in Saint-Eustache, Lower Canada.

Jean-Olivier Chénier belonged to a farming family that also had some involvement in trade. His grandfather, François Chénier, had married Suzanne-Amable Blondeau, daughter of a family of wealthy merchants established in Montreal by the end of the 18th century. When Jean-Olivier was baptized, his godfather was Jean-Baptiste Trudeau (Truteau), a fur trader and explorer. Chénier seems to have owed his education to a patron, Montreal doctor René-Joseph Kimber. Wishing to follow in Kimber’s footsteps, in 1820 Chénier began training under his guidance. He was licensed to practise on 20 Feb. 1828, when he was 21.

The young doctor moved that year to Saint-Benoit (Mirabel), a village in York riding, where he soon became involved in politics. The preceding year, in a confrontation between the House of Assembly and Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay] over the question of supplies, the governor had prorogued parliament in March, and called a general election for July. When the new house chose Louis-Joseph Papineau* as speaker, Dalhousie prorogued it in November, attempting thus to assert the rights of the crown and the colonial executive. Those supporting the assembly’s rights retaliated by holding public meetings, organizing the famous petition to the imperial parliament bearing 80,000 signatures, and sending a delegation [see Denis-Benjamin Viger*] to London. York riding took an active part in this dispute. In the July elections York voters chose the Patriote party candidates, Jacques Labrie*, a doctor at Saint-Eustache, and Jean-Baptiste Lefebvre, a merchant in Vaudreuil, over those of the English party, Nicolas-Eustache Lambert* Dumont, the co-seigneur of Mille-Îles, and John Simpson*, the customs collector at Coteau-du-Lac. At Saint-Benoit in particular a symbolic gesture of opposition to the authorities was made by notary Jean-Joseph Girouard*, a captain in the Rivière-du-Chêne militia battalion, and his political friends, who neglected that summer to proceed with the annual embodying of the militia. In 1828 Chénier was one of seven persons, including Labrie and Girouard, accused of obstructionism by the officer commanding the militia, Lieutenant-Colonel Lambert Dumont.

Following the accidental death of Jean-Baptiste Lefebvre, Chénier in 1829 joined in helping William Henry Scott*, a Saint-Eustache merchant, to win election for York. In the 1830 general election, the first to be held after a redrawing of the electoral map that split York into the three ridings of Deux-Montagnes, Vaudreuil, and Ottawa, Chénier assisted Labrie and Scott in winning Deux-Montagnes. On 26 Sept. 1831, at Saint-Eustache, he married Labrie’s daughter Zéphirine. Labrie died a month later, and in December 1831 Chénier was largely instrumental in getting Girouard elected for Deux-Montagnes. In June 1832, shortly after the by-election in Montreal West during which troops opened fire and killed three people [see Daniel Tracey*], he was one of a group of leading citizens who urged the freeholders of Deux-Montagnes County to attend a meeting at Saint-Benoit “for the purpose of agreeing upon the most effective ways of preventing monopoly, speculation, and any selective system in the matter of settling uncultivated lands.” At the ensuing meeting he was appointed to a committee of 30 persons, 6 from Saint-Benoit, charged with looking out for the Canadians’ interests. According to most historians, Chénier did not leave Saint-Benoit to live in Saint-Eustache until 1834.

The 1834 elections, held after the 92 Resolutions had been passed, revealed in striking fashion the popularity of the Patriote party. Scott and Girouard won in Deux-Montagnes, despite violence and intimidation. These elections demonstrated the split between the so-called lower and upper ends of the riding – the part comprising the villages of Saint-Eustache, Saint-Benoit, and Sainte-Scholastique (Mirabel), which had been settled earlier and was largely French-speaking, and the part taking in the seigneury of Argenteuil and the townships of Chatham and Grenville, which had been populated more recently and was in good measure English-speaking. In his description of the celebration that was held after the elections, published in Relation historique des événements de l’élection du comté du lac des Deux Montagnes en 1834; épisode propre à faire connaître l’esprit public dans le Bas-Canada, Girouard himself mentioned Chénier as one of the principal architects of the victory of the Patriote cause. He added: “But it was to Dr Chénier especially that the voters showed how satisfied they were with his energetic and tireless leadership and his courage in the struggle; throughout, his lady, the worthy daughter of the late Dr Labrie, had unceasingly welcomed into her home, night and day, the habitants from outlying regions who came by the hundreds to ask her for shelter, since there was no inn in the village open to Canadians. They expressed their gratitude to this lady openly.”

In the years following, Chénier was active in the public meetings held in Deux-Montagnes County. On 11 April 1836, for example, along with Luc-Hyacinthe Masson*, a doctor from Saint-Benoit, he served as secretary for a meeting at Saint-Benoit where one of several resolutions urged people to abstain from buying “goods and products of British factories” and the idea of founding national factories was put forward. At the big meeting held on 1 June 1837 at Sainte-Scholastique as part of the protest against Lord John Russell’s resolutions, Chénier was named to the permanent committee charged with giving effect to the meeting’s proceedings. He reportedly made known his determination at that time, declaring, “What I say, I think, and I shall do it; follow me and I give you permission to kill me if ever you see me flee.” In the period from June to November 1837 the committee organized a dozen meetings. Chénier was one of its leading members, along with Girouard, Masson, and Joseph-Amable Berthelot, a Saint-Eustache notary.

There was constant friction in Deux-Montagnes County in the summer of 1837. The Patriotes’ opponents complained that they were being subjected to harassment and even violence. They resorted to making denunciations to the authorities. The government at first intended to hold an investigation and proceed with arrests, but decided instead to brandish threats of dismissal; it succeeded mainly in prompting the resignation of some justices of the peace and militia officers. A meeting at Saint-Benoit on 1 October, described by the Montreal newspaper Le Populaire in an article entitled “La révolution commence,” decided that the time had come to elect justices of the peace and to let the militiamen in each parish elect their officers. Chénier served as secretary for the subsequent meeting held on the Saint-Joachim concession at Sainte-Scholastique on 15 October, and he was one of the 22 magistrates who were voted in. On 23 October he participated with Girouard and Scott in the Assemblée des Six Comtés at Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu. At that time Scott stood out as the principal Patriote leader in Saint-Eustache, with Chénier close behind. Scott, Chénier, and Joseph Robillard, a mason and merchant, were the only ones who were members of both the permanent committee and the improvised judicial and militia organizations. Among the other leaders were notary Berthelot, surveyor Émery Féré, and farmer Jean-Baptiste Bélanger.

When arrests began on 16 Nov. 1837, Chénier was on the list of people for whom warrants had been issued. The following day Amury Girod arrived in Deux-Montagnes County and, claiming that he had the backing of Louis-Joseph Papineau and a small council of war held at Varennes, near Montreal, with Papineau, Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan*, and Jean-Philippe Boucher-Belleville*, he imposed himself as general of the forces in the county that had been mobilized to resist and to set up a provisional government. But the “general,” a striking figure who was surrounded with aides-de-camp recruited from among young Montreal lawyers, had to leave a good deal of autonomy to Chénier, who was in command of the camp at Saint-Eustache, since he himself had to travel to and fro between Saint-Benoit and Saint-Eustache. Chénier had his men and Girod his own when the two groups tried to seize arms belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company and the indigenous people residing at Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes (Oka).

The purchase and seizure of arms and food and the conduct of intelligence activities and mustering, rather than actual military training, made up Chénier’s day to day work as commander. After a defeat at Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu on 25 November the Patriote leaders found it difficult to keep up their men’s morale. Early in December Scott and Féré, who were against the use of arms, withdrew from the movement, considering it thenceforth hopeless. The parish priest of Saint-Eustache, Jacques Paquin, his assistant, François-Xavier Desève, and their friend François-Magloire Turcotte, the curé of Sainte-Rose (at Laval), tried to point out that it was madness to entertain any notion of beating the forces of the government, now preparing to attack the insurgents.

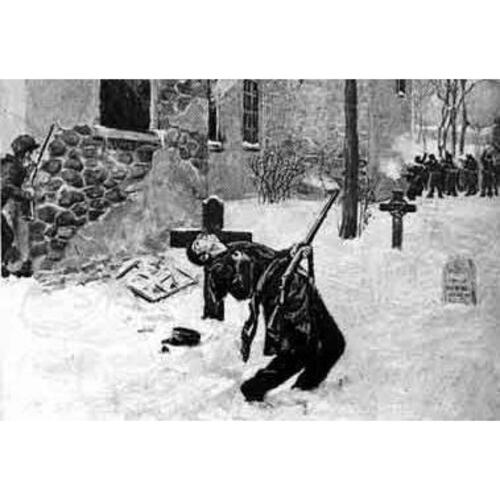

On 14 Dec. 1837 Sir John Colborne*’s troops, who had come from Montreal by way of Île Jésus, and local volunteers under Maximilien Globensky* attacked Chénier’s men. They had barricaded themselves in the church, presbytery, convent, and surrounding houses in Saint-Eustache. Chénier’s followers came mainly from Saint-Eustache, Sainte-Scholastique, and Saint-Jérôme. Girod had made off in the direction of Saint-Benoit, and the handful of young men from Montreal, who claimed they belonged to the central organization, had also left the scene. It was an uneven confrontation: of Chénier’s force, smaller in number and relatively poorly armed, some 40 men whose names are known were killed, and there were probably as many more unknown victims. Chénier himself was killed as he was trying to get out of the burning church. He had just turned 31.

There is some question whether the victorious British army treated Chénier’s body with respect [see Daniel Arnoldi] . Much has been written about the matter, particularly in the period 1883–84, when Charles-Auguste-Maximilien Globensky published La rébellion de 1837 à Saint-Eustache and Laurent-Olivier David* Les patriotes de 1837–1838. In 1952–53 once more, in the Revue de l’université Laval, Émile Castonguay, using the pseudonym Bernard Dufebvre, defended Globensky’s thesis and Robert-Lionel Séguin that of David; and in the 1970s the question resurfaced in the Saint-Eustache newspaper La Victoire. The facts themselves are less important than the implied symbolic significance. In any event, the controversy does not concern Chénier himself so much as it does the conduct of the British soldiers.

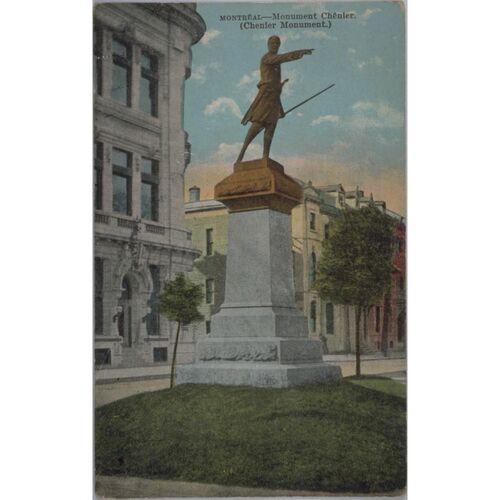

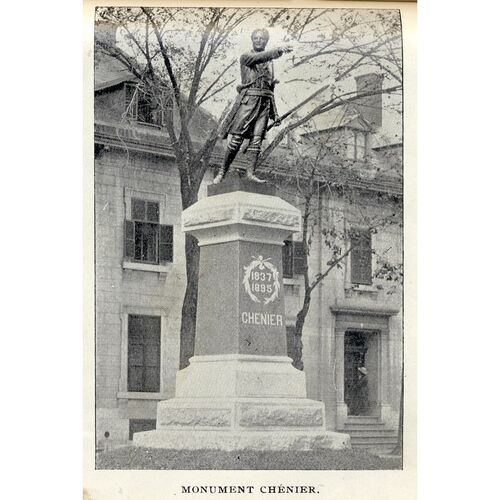

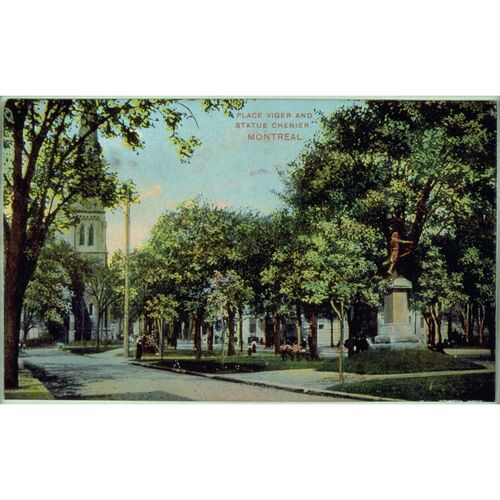

The rather extraordinary story of the monuments proposed to Chénier’s glory also demonstrates the importance that a matter of symbolic value may possess. In 1885, in the context of the David–Globensky debate and the Riel affair [see Louis Riel*], it was suggested that a monument be raised to Chénier at Saint-Eustache, the initiative being taken by David Marsil, a doctor who was mayor of Saint-Eustache from 1871 to 1875 and a defeated Liberal candidate in 1878, and by his political friends. But the opponents of the project used their influence to block it – and even to turn the occasion into an unveiling of a commemorative plaque in honour of Jacques Paquin. In 1891 Marsil thought that he could have Chénier’s remains transferred to the monument that had been raised in 1858 in Montreal's Catholic cemetery of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges in memory of the Patriotes who had died in 1837–38. He had the body exhumed from the section of the cemetery of Saint-Eustache reserved for those who had died unbaptized. The words “Here rest his remains” were even engraved under Chénier’s name on the monument. But Édouard-Charles Fabre*, the archbishop of Montreal, refused to allow the transfer of the remains and the ceremony. Marsil then served on a committee, created in 1893, that could count on Honoré Mercier*’s influence, and it gave Chénier his monument in Square Viger in Montreal on 24 April 1895. In 1937, on the centenary of his death, a monument to Chénier was raised in Saint-Eustache. His remains were held by the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal until July 1987, when they were interred in the consecrated portion of the cemetery at Saint-Eustache.

All of Chénier’s children had predeceased their father. His wife became a schoolteacher and soon married Louis-Auguste Desrochers, an office holder and music teacher. In 1852, having examined her claims, the Rebellion Losses Commission paid her a small indemnity for her share in the property that she had owned in community with Chénier and that she had lost when their house was burned in 1837. She won her case thanks in part to Jean-Joseph Girouard and his second wife, Émélie Berthelot, with whom she was friends. Other members of Chénier’s family survived him: a brother, Victor, who lived at Longueuil near Montreal, two sisters who went to live at Montebello, and a cousin, Félix, a young notary at Saint-Eustache who also had been involved in the events of 1837–38.

According to an oral statement reported by Joseph-Arthur-Calixte Éthier in a lecture delivered and published in 1905, Jean-Olivier Chénier was “a little man with broad shoulders, well built, not disagreeable, polite, but hardly timid.” There is no question that he died bravely. Of course, those who hold the general view that the cause was legitimate and the action right will speak of courage and sincere generosity, whereas those who hold the contrary view will speak rather of stubbornness and baneful influence. Emile Dubois, the historian of the rebellion of 1837 in the Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes region, gives a qualified but on the whole sympathetic picture of Chénier’s character. Fernand Ouellet, historian of the insurrectional movement as a whole, reproaches the Patriote leaders for two reasons: their ambivalence about resorting to arms, and their tendency to refuse, up to the very end, to assume the consequences of the mobilization to which their words and actions had led. Yet he makes an exception for Wolfred Nelson* at Saint-Denis on the Richelieu and for Chénier at Saint-Eustache. In his view, these two distinguished themselves by the coherence and consistency of their conduct.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 10 déc. 1806; CE6-11, 26 sept. 1831, 14 déc. 1837. ANQ-Q, E17/13, nos.665, 691, 695, 744; E17/ 14, nos.767, 770, 773, 775, 779–81, 788, 793, 800. BVM-G, Fonds Ægidius Fauteux, notes compilées par Ægidius Fauteux sur les patriotes de 1837–38 dont les noms commencent par la lettre C, carton 3. PAC, RG 4, B28, 51: 1238–41. Émélie Berthelot-Girouard, “Les journaux d’Émélie Berthelot-Girouard,” Béatrice Chassé, édit., ANQ Rapport, 1975: 1–104. [J.-J. Girouard], Relation historique des événements de l’élection du comté du lac des Deux Montagnes en 1834; épisode propre à faire connaître l’esprit public dans le Bas-Canada (Montréal, 1835; réimpr. Québec, 1968). [P.-G. Roy], Premier rapport de la Commission des monuments historiques de la province de Québec, 1922–1923 (Québec, 1923), 182, 243–46. F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891), 56. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer. Fauteux, Patriotes, 174–76. Wallace, Macmillan dict. Béatrice Chassé, “Le notaire Girouard, patriote et rebelle” (thèse de d. ès l., univ. Laval, Québec, 1974). L.-O. David, Le héros de Saint-Eustache: Jean-Olivier Chénier (Montréal, s.d.); Patriotes, 45–52, 147–51. Émile Dubois, Le feu de la Rivière-du-Chêne; étude historique sur le mouvement insurrectionnel de 1837 au nord de Montréal (Saint-Jérôme, Qué., 1937), 122. J.-A.-C. Éthier, Conférence sur Chénier (Montréal, 1905). Filteau, Hist. des patriotes (1975), 369–71. [C.-A.-M. Globensky], La rébellion de 1837 à Saint-Eustache avec un exposé préliminaire de la situation politique du Bas-Canada depuis la cession (Québec, 1883; réimpr. Montréal, 1974), 220–24. Laurin, Girouard & les patriotes, 45. Raymond Paiement, La bataille de Saint-Eustache (Montréal, [1975]). Gilles Boileau, “Mais qui donc était Chénier?” La Victoire (Saint-Eustache, Qué.), 14 oct. 1970: 12. C.-M. Boissonnault, “La bataille de Saint-Eustache,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval, 6 (1951–52): 425–41. Gaston Derome, “Le patriote Chénier,” BRH, 59 (1953): 222. Bernard Dufebvre [Émile Castonguay], “À propos du cœur de Chénier,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval, 7 (1952–53): 905–10; “Encore à propos des patriotes,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval, 8 (1953–54): 41–48. Ægidius Fauteux, “Le docteur Chénier,” BRH, 38 (1932): 715–17. Clément Laurin, “David Marsil, médecin et patriote de Saint-Eustache,” Soc. d’ hist. de Deux-Montagnes, Cahiers (Saint-Eustache), été 1978: 27–37. R.-L. Séguin, “À propos du cœur de Chénier,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval, 7: 724–29; “La dépouille de Chénier fut-elle outragée?” BRH, 58 (1952): 183–88; “Questions et réponses à propos des patriotes,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval, 8: 32–40. Soc. d’ hist. de Deux-Montagnes, Cahiers, 5 (1982), no. 2.

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE606-S9, 2 août 1832, 2 déc. 1833; CE606-S11, 8 oct. 1834, 14 sept. 1837.

Cite This Article

Jean-Paul Bernard, “CHÉNIER, JEAN-OLIVIER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chenier_jean_olivier_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chenier_jean_olivier_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Paul Bernard |

| Title of Article: | CHÉNIER, JEAN-OLIVIER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |