As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

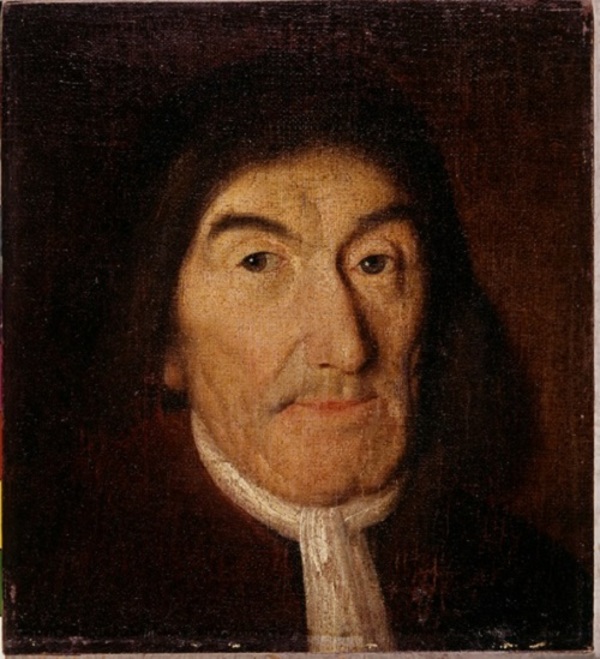

HENNEPIN, LOUIS (baptized Antoine), priest, Recollet, missionary, explorer, historiographer; b. 12 May 1626 at Ath, in Belgium, son of Gaspard Hennepin, a butcher, and of Norbertine Leleu; d. c. 1705.

Louis Hennepin attended the École latine in the town of Ath (province of Hainaut), and did his classical studies there. Around the age of 17 he donned the rough homespun of the Franciscans at the convent of Béthune (department of Pas-de-Calais), and began his noviciate under the direction of Father Gabriel de La Ribourde*. He continued his studies at the convent of Montargis (department of Loiret), with Father Paul Huet* as his master, then entered the priesthood.

Imbued with sincere missionary fervour, and adventurous into the bargain, he immediately sought to give free expression to his zeal and his natural inclination. After a period of time spent with his sister Jeanne at Ghent, where he acquired some knowledge of Flemish, he set out for Rome with the object of interesting the higher authorities of the order in his missionary ideal. He received permission to visit a number of sanctuaries and monasteries in Italy and Germany on the way back, “Whereby,” he wrote, “I began to satisfy my natural curiosity.” When he reached the low countries Hennepin settled at Hal (province of Brabant), on the order of the provincial superior, Father Guillaume Herincx. For a year he carried on a preaching ministry, then he went to Artois, staying in the convents situated along the coast: Biez, Calais, Dunkirk. His romantic mind caught fire when he heard the sailors’ stories, some of them strange ones. Indeed Hennepin, hiding behind tavern doors, drank in the adventurous seamen’s words. “I would have spent whole days and nights in this occupation, which I found so pleasant,” he wrote in the Nouvelle découverte, “because I always learned something new about the beauty, fertility, and wealth of the countries where these people had been.”

During the war started by Louis XIV in 1672 he devoted himself in Holland to the care of the wounded and sick; in 1673 he spent eight months in this fashion at Maastricht (Netherlands). A contagious illness obliged him to rest for a time; once he was cured, he took up his task again and was present at the battle of Seneffe (Hainaut) on 11 Aug. 1674.

The following year, on 22 April 1675, Louis XIV asked the Recollets to send five missionaries to New France in the near future. The superiors chose Fathers Chrestien Le Clercq*, Luc Buisset, Zénobe Membré*, Louis Hennepin, and Denis Moquet (the latter, who was sick, stayed in Europe). At the end of May 1675, with Cavelier* de La Salle, the missionaries left Europe.

The eager missionary lost no time in getting to work. He gave the Advent and Lent sermons at the Hôtel-Dieu of Quebec on Bishop Laval’s invitation, and went through countryside and village, preaching the gospel at Cap-Tourmente, Trois-Rivières, Sainte-Anne de Beaupré, and Bourg-Royal. In the spring of 1676 he went to Lake Ontario to replace Father Léonard Duchesne at Cataracoui (Fort Frontenac, now Kingston, Ont.). Hennepin’s activity never flagged; with his confrère Luc Buisset, he built a “mission house” which was soon frequented by many Iroquois.

In 1678 Hennepin went back to Quebec to take up priestly duties there. La Salle, who had returned from Europe (15 September) with royal authorization to explore the western part of New France, handed the missionary a letter from Father Hyacinthe Lefebvre, his provincial superior; the latter requested Hennepin to accompany the explorer on his travels. Armed with the articles indispensable for his task of disseminating the gospel, the missionary arrived at Fort Frontenac.

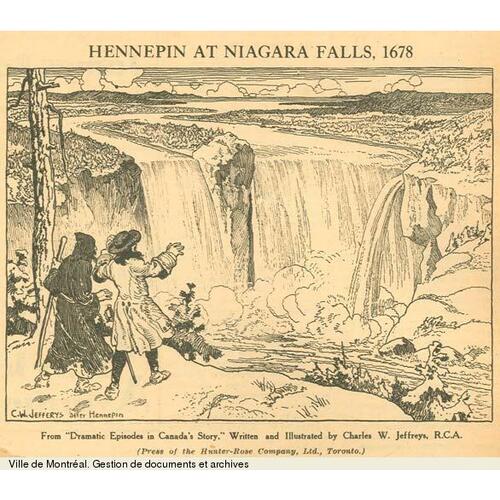

A few days later (18 November) the odyssey began: 16 passengers boarded a brigantine of 10 tons, commanded by the Sieur La Motte* de Lucière; with about a month’s advance on La Salle, Lucière’s mission was to build a fort and a bark at Niagara. Braving the inclemency of an already late season, the sailing-ship succeeded in reaching the Niagara River on 6 December; on 8 December it was at Niagara Falls, “the most beautiful and altogether the most terrifying waterfall in the universe.”

It was not long before the travellers encountered the first difficulties of the daring undertaking: the disquieting presence of Indians ever on the watch, the lack of provisions, and the discontent and grumblings of the members of the crew. They nonetheless laid a bark down as early as January (1679), and built Fort Conti during the winter. On 11 May, on La Salle’s orders, Hennepin went down to Fort Frontenac to bring back to Niagara his two confrères: Gabriel de La Ribourde and Zénobe Membré.

From 7 Aug. 1679 to 29 Feb. 1680 Hennepin accompanied Cavelier de La Salle on his explorations [for the description of this voyage see Cavelier* de La Salle]; from Fort Crèvecœur La Salle then sent him with an advance guard towards the upper Mississippi. Together with Michel Accault and Antoine Auguel, dit Le Picard Du Guay, Hennepin left in a canoe carrying a cargo worth about 1,100 livres. Hennepin claimed that he made his way to the mouth of the Mississippi between 29 February and 25 March; he had returned from there by 10 April. “After paddling all night, heading in a northerly direction,” wrote Hennepin, “we found ourselves quite far from [the] mouth [of the Illinois river].” On 11 April, at two o’clock in the afternoon, there suddenly appeared 33 canoes carrying Sioux Indians on a warlike expedition against neighbouring tribes. The French were seized immediately, but their lives were spared thanks to the pipe of peace and the gifts that they proffered; but the Sioux forced the three travellers to follow them to their village. In the midst of the war fleet the French canoe, handled by vigorous Indians, went about 250 leagues along the River Colbert (Mississippi). On “the nineteenth day of navigation, five leagues” from a waterfall that Hennepin was to name “Saint-Antoine de Pade,” the Indians went ashore, hid their canoes, and broke that of the French to pieces. Then followed a forced march of five days over marshes, lakes, and rivers to the Sioux village, situated in the Thousand Lakes region. When the escort finally reached the village, around 21 April 1680, Hennepin was exhausted; a steam bath after the Indian fashion revived him. Having been adopted by the chief, Aquipaguetin, and his six wives, Father Louis was able to take advantage of his painful captivity to study the habits, customs, and language of the tribe.

In July the village scattered for the hunting season. After “making a hole in the ground in which to put [his] silver chalice and [his] papers until he returned from hunting,” Hennepin went south with the “Great Chief Ouasicoudé.” During this expedition on the Wisconsin River there occurred the chance meeting with Daniel Greysolon Dulhut and five Frenchmen, who were visiting the Sioux (25 July); on 14 Aug. 1680 all were back in the village.

At the end of September the great chief of the Sioux gave the French permission to leave, and even drew on a piece of paper the route they could follow. “With this map,” wrote Hennepin, “we set out, eight Frenchmen in two canoes.” After wintering at Michilimackinac, the travellers started out for Quebec in Easter week (between 6 and 13 April 1681). The same year Louis Hennepin landed at Le Havre and retired to the convent of Saint-Germain-en-Laye to write up an account of his odyssey.

The Description de la Louisiane, published on 5 Jan. 1683 in Paris, had the most unqualified success: the work went through several editions, and was translated into Italian, Dutch, and German. The monk became a celebrity overnight for readers hungering for exotic stories and delighted by the description of the Mississippi and its rich valley. For a time the Recollet’s name was honoured: he was vicar of the convent of Le Cateau-Cambrésis in 1683, and superior of the convent of Renty from 1684 to 1687. But for reasons that are still not known, Hennepin suddenly fell into disgrace; he was relegated to the convent of Saint-Omer, and subsequently expelled from the ecclesiastical province of Artois. In Hainaut, where he took refuge, the Recollet resided for five years (1687–92) at Gosselies, as chaplain of the Recollet Sisters. Once more harried by the civil and ecclesiastical authorities, Hennepin had to leave this last residence. It was then that he tried to interest the king of England in the rich countries recently discovered. Thanks to the protection of William Blathwayt, William III’s secretary of war, and to the intervention of the Baron de Malqueneck, the Elector of Bavaria’s favourite, Hennepin obtained permission to go to Holland at the king’s expense, in order to publish his books and prepare for his crossing to America.

In 1696 Louis Hennepin, dressed in lay attire (the wearing of the ecclesiastical or religious habit being forbidden in Holland), left Belgium and made for Amsterdam, where he counted on publishing his works. His plan was thwarted by “serious obstacles.” By agreement with the Count of Athlone, a Dutch general in William III’s service, Hennepin set out for Utrecht. At first he lodged at the house of Martin van Blacklandt; but the latter’s wife, a shrew tainted with jansenism, made life impossible for him. He then withdrew to the house of a pious widow, Dame Renswore.

For three or four months Hennepin assisted the Dominican Louis van der Dostyne, the priest of Notre-Dame-du-Rosaire; his ministry embraced for the most part French-speaking refugees. On 1 March, in the name of their co-religionists, 58 citizens signed a petition asking authorization to establish a missionary station for French-speaking Catholics at Utrecht. Their request remained unanswered, and on 5 May Hennepin, exasperated by the slanderous rumours that continued to circulate with regard to him, began to preach, despite a formal interdict imposed by Pierre Codde, the vicar apostolic and an uncompromising Jansenist. The latter ordered Father Dostyne to close his chapel to the Recollet, then, from the pulpits of the churches of Utrecht, forbad the churchgoers to attend Father Hennepin’s sermons or masses said by him, on pain of sin (2 June).

This fresh conflict with the religious authorities of Holland still did not succeed in bringing this extraordinary man to heel. He found the time and the means to publish the Nouvelle découverte in 1697, then the Nouveau voyage in 1698, two works which recount his alleged trip down the Mississippi and add numerous details concerning his short stay in America and his troubled life in Europe. In his third book he directly attacked the vicar apostolic. Indeed La morale pratique du Jansénisme (1698) exposed the vexatious conduct of Pierre Codde and his acolyte Jacob Cats towards him, denounced Dutch jansenism, and revealed some of Hennepin’s personal grievances. Shortly afterwards the authorities of the city of Utrecht gave him notice to leave.

Before quitting this city for Rome (around 18 July), Hennepin took a step as surprising as it was unaccountable; he called on the French ambassador at The Hague, M. de Bonrepaus, requesting him to obtain permission for him to return to France and go back to America. “One might thus prevent this restless spirit from prompting the English and the Dutch to set up other establishments in America,” the ambassador wrote on 26 June. In reply to this letter, Pontchartrain [Phélypeaux] informed the ambassador on 9 July that the king of France would grant the request. The following year (May 1699), however, Louis XIV changed his mind; he plainly forbad Hennepin to set foot on American soil on pain of arrest.

From 1699 on Father Hennepin’s life still remains rather obscure to us; a few salient facts, however, permit us to reconstruct its last moments. In December 1699, while at Rome, he sought and obtained authorization to retire to the convent of Saint-Bonaventure-sur-le-Palatin, “for the purpose of attending to the salvation of his own soul there, after working for so many years for the salvation of his fellow-men.” Two years later (March 1701) we find him at the convent of Ara cœli, on the Capitoline Hill; apparently, we are informed in a document, he had “wheedled his way around Cardinal Spada, who was supplying funds for a new mission to the Mississippi countries.” Finally, from Belgium (July 1701), Hennepin dispatched to the sovereign pontiff a petition “to be granted the right and authority to devote himself to the conversion of apostate religious in Holland”; this permission was not granted.

Louis Hennepin’s story is still incomplete. In the present state of our knowledge we can at best put forward hypotheses on the most controversial problems raised by the life of this turbulent personage. Belgian by birth but French by education, he had lived in an environment of intrigues and cabals. The Description de la Louisiane earned him a glory and celebrity that were rapidly effaced by a sensational fall from favour; he was expelled from France, then pursued, hunted down to the point where he no longer felt safe, “whatever service I had rendered in all the places I had lived in until then.” It was at that time that he took refuge with William III, an ally of his country. In taking this step, should Hennepin be seen in the guise of an adventurer with few qualms as to what methods he adopted to realize his plans? As the reasons for his expulsion are still ill-defined, it is rather difficult to answer this question satisfactorily.

A man of well-tempered, enterprising, and combative character, Hennepin had to collaborate with one whose personality was as strong as his: Cavelier de La Salle. Clashes occurred, inevitably. Did La Salle subsequently become the intriguer who worked through the civil and religious authorities to bring about the Recollet’s downfall? Hennepin affirms this, but it remains to be proved.

When he came to America there was an underlying rivalry between Jesuits and Recollets. The first enjoyed the support of the bishop, the second, brought to Canada to counterbalance the influence of the sons of St Ignatius, were given a more receptive hearing by the civil authorities, who were even to criticize the bishop of Quebec for his distrust of the Recollets. In such a context, the stir made by this restless monk during his stay in New France can easily be guessed at. Moreover, mischievous rumours and libellous accusations were rife concerning the Recollet, who laid himself so readily open to reproaches. Too many writers, working from these malicious reports, have painted an unfavourable picture of him.

Louis Hennepin had a rather strange personality, made up of a mixture of qualities and defects that were equally marked. Undoubtedly, in Europe and America, he was a zealous propagator of the faith, sincerely attached to the Church; his Morale pratique du jansénisme is ample proof of this. In his autobiography – nothing for the moment justifies our calling in question the sincerity of this testimony, despite undeniable exaggerations – he appears again to be a generous man, giving of himself unstintingly. In Europe he lavished care upon the injured and the sick at the risk of his own life; when he was superior at Renty he rebuilt the convent, at Gosselies he directed the work for the reconstruction of the chapel. During his expeditionary voyage, in America, he intervened to put down revolts, prevent defections, and calm the Indians; in 1679, when they had to disembark in Lake Dauphin, he did not hesitate to jump into the water and pull the canoe to the shore, carrying “our worthy, elderly Recollet [Gabriel de La Ribourde]” on his shoulders.

A fearless disseminator of the faith, but also an independent person, disagreeable into the bargain, he more than once antagonized his associates, provoked dissension, and made enemies for himself. At the time of the crossing in 1675, imbued with a compulsive zeal, he took to task a group of girls, on the pretext that they “were making a lot of noise with their dancing, and thus preventing the sailors from getting their rest during the night”; this intervention started up a rather serious verbal battle between the monk and Cavelier de La Salle. In Canada he administered the sacraments without the bishop’s authorization; during his captivity among the Sioux, he made enemies of his two companions, Michel Accault and Antoine Auguel. In France, he firmly opposed his superiors who wanted to send him back to America; finally, in Holland, he preached and celebrated mass despite the opposition of the ecclesiastical authorities. All the wrongs were perhaps not on Father Hennepin’s side, but this conduct offered material for the most regrettable rumours.

Should one encumber the picture by including in it such unflattering epithets as plagiarist, lying, shameless, impudent, which have been lavishly applied to him by many authors? Did Hennepin really go down the mighty Mississippi in 30 days as he claimed he did? “I assure you before God that my account is faithful and honest, and that you can believe everything that is reported there.” In his Description de la Louisiane Hennepin warned the reader that he proposed to write another book. Did he then make no mention of certain facts “in order not to cause distress to the Sieur de La Salle”? The studies so far undertaken, with the aim of answering these questions, are distinctly unfavourable to Louis Hennepin. In any case, these points remain to be cleared up before a decisive answer can be given.

In his day, Louis Hennepin was the most fashionable of popular authors; his work had no fewer than 46 editions. No doubt as a writer he does not possess the flavour of a Gabriel Sagard*, for example; he was not always careful about details, and his style often lacks elegance. Nevertheless, he writes spontaneously, sometimes gives iridescent colours to his pictures, paints enthusiastically the flora and fauna of the country, and describes perceptively the Indian tribes, their way of life, their customs, and their beliefs.

Let us at least leave to this enigmatic personage the glory which is his due: that of having shared in the discoveries made in New France and of having succeeded in making them known to Europe.

Louis Hennepin, Description de la Louisiane, nouvellement découverte au sud-ouest de la Nouvelle-France par ordre du Roy. Avec la carte du pays; les mœurs et la manière de vivre des sauvages (Paris, 1683); Nouvelle découverte d’un très grand pays situé dans l’Amérique entre Le Nouveau-Mexique et la mer glaciale. Avec les cartes et les figures nécessaires et de plus l’histoire naturelle et moralle et les avantages qu’on en peust tirer par l’établissement des colonies. Le tout dédié à sa majesté Britannique Guillaume III (Utrecht, 1697); Nouveau voyage d’un pars plus grand que l’Europe. Avec les réflections des entreprises du Sieur de la Salle sur les mines de Ste Barbe etc. Enrichi de la carte, de figures expressives, des mœurs et manière de vivre des sauvages du nord et du sud, de la prise de Québec, ville capitalle de la Nouvelle-France, par les Anglois, et avantages qu’on peut retirer du chemin racourci de la Chine et du Japon, par le moien de tant de vastes contrées et de nouvelles colonies. Avec approbation et dédié à sa majesté Guillaume III Roy de la Grande Bretagne (Utrecht, 1698); La morale pratique du jansénisme . . . (Utrecht, 1698).

Father Hennepin’s works have been published in several editions in various languages: see Jérôme Goyens, “Coup d’œil sur les œuvres littéraires du père Hennepin,” Archivum Franciscanum Historicum (Florence, Italy), XVIII (1925), 341–45; and Hugolin [Stanislas Lemay], Bibliographie des bibliographies du P. Louis Hennepin (Notes bibliographiques pour servir à l’histoire des Récollets au Canada, IV, Montréal, 1933). The following are some of the most important and most recent studies on Father Louis Hennepin: Jean Delanglez, Hennepin’s Description of Louisiana, a critical essay (Institute of Jesuit history pub., Chicago, 1941); Jérôme Goyens, “Le P. Louis Hennepin, o.f.m., missionnaire au Canada au XVIIe Siècle. Quelques jalons pour sa biographie,” Archivum Franciscanum Historicum, XVIII (1925), 318–41, 473–510. [Goyens’ work should be used with caution; his arguments are not always firmly documented, and some of his conclusions have been shown to be wrong. j.–r.r.]. Father Hugolin [Stanislas Lemay] has published a series of articles on Hennepin in the journal Nos Cahiers: “Son allégeance politique et religieuse,” I (1936), 316–46; “Les Observationes de Pierre Codde, vicaire apostolique de Hollande,” II (1937), 5–37; “Une obédience pour l’Amérique en 1696, et départ pour la Hollande,” II (1937), 149–79; “Aux prises avec les jansénistes,” II (1937), 245–80; “A Utrecht, ses efforts pour y obtenir une station missionnaire en 1697,” II (1937), 375–419; “Devant Rome,” III (1938), 17–68; “A Paris, 1682,” III (1938), 105–40; “Devant l’histoire,” III (1938), 245–76, 341–74. As well, Lemay has published “Une étude bibliographique et historique sur La Morale pratique du jansénisme du père Louis Hennepin,” RSCT, 3d ser., XXXI (1937), sect.i, 127–49. Finally, he has gathered together and published some documents under the title Bibliographie du Père Louis Hennepin, récollet. Les pièces documentaires (Montréal, 1937). Armand Louant, “Le P. Louis Hennepin. Nouveaux jalons pour sa biographie,” Revue d’histoire ecclésiastique (Louvain, Belgium), XLV (1950), 186–211; LII (1957), 871–76; “Précisions nouvelles sur le Père Hennepin, missionnaire et explorateur,” Bulletin de la classe des lettres et des sciences morales de l’Académie royale de Belgique (Brussels), XLII (1956), 5e sér., 215–76. [The author examines Hennepin’s case in the light of the latest scientific studies and new documents discovered in governmental archives at Mons; two autograph letters in particular identify Louis as one of Gaspard Hennepin’s four sons. j.r.r.] C.-M. Morin, “Du nouveau sur le récollet Louis Hennepin,” RHAF, I (1947–48), 112–17. H.-A. Scott, “Un coup d’épée dans l’eau, ou, Une nouvelle apologie du P. Louis Hennepin,” RSCT, 3d ser., XXI (1927), sect.i, 113–60. J. Stengers, “Hennepin et la découverte du Mississipi,” Bulletin de la société royale belge de géographie d’Anvers, 1945, 61–82.

Cite This Article

Jean-Roch Rioux, “HENNEPIN, LOUIS (baptized Antoine),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hennepin_louis_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hennepin_louis_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Roch Rioux |

| Title of Article: | HENNEPIN, LOUIS (baptized Antoine) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |