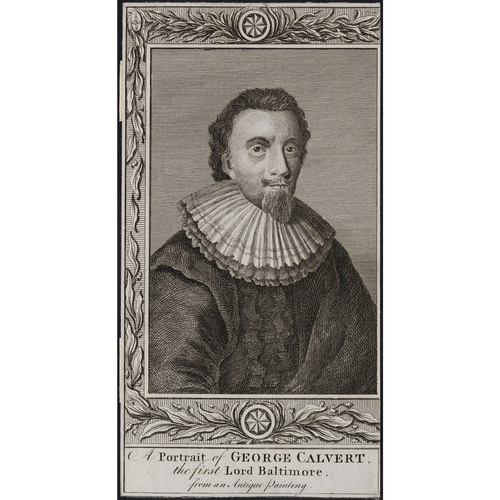

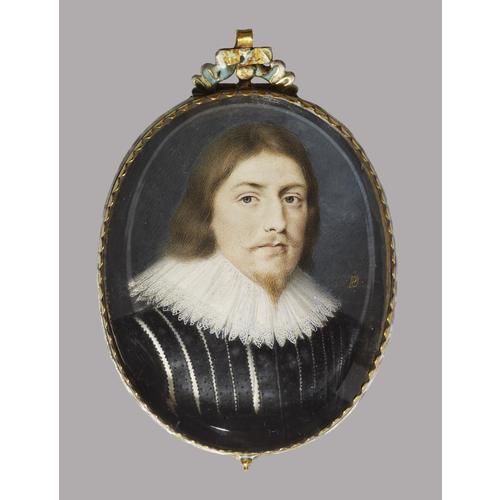

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CALVERT, GEORGE, 1st Baron Baltimore, colonizer in Newfoundland; b. at Kipling, Yorkshire, c. 1580, the son of Leonard Calvert and his wife Alice, daughter of John Crosland of Crosland; d. 15 April 1632 in England.

George Calvert was educated at Trinity College, Oxford, and, in 1606, was appointed private secretary to Sir Robert Cecil. Advancing rapidly in the public service, he became clerk of the Privy Council in 1608 and was elected M.P. for Bossiney in 1609. Knighted in 1617, two years later he was made secretary of state and a member of the Privy Council. One of the leaders of the court party, he proved an effective exponent of the royal policy in Parliament until his conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1625 led to his resignation as secretary of state. On his retirement from politics he was created Baron Baltimore of county Longford, Ireland, as a reward for his loyalty to the king.

He now had leisure to devote to the colony in Newfoundland which he had acquired from William Vaughan. Four years earlier, in 1621, he had despatched Capt. Edward Wynne with 12 men to establish a small settlement there at Ferryland, about 50 miles south of St. John’s. This struggling colony was strengthened in the following year by the arrival of a second group of settlers, 22 in number, under the command of another of Calvert’s agents, Capt. Daniel Powell. Encouraged by glowing reports from Wynne and Powell exaggerating the progress of the settlement, Calvert on 7 April 1623 procured a royal charter for his plantation, officially styled “the province of Avalon,” a name, according to Lloyd in his State Worthies, adopted “in imitation of old Avalon in Somersetshire, where Glastonbury stands, the first-fruits of christianity in Britain, as the other was in that part of America.”

Two years later, Calvert made plans to visit Avalon but was prevented from doing so because the ship Jonathan on which he intended to sail was requisitioned for the king’s service. By 1627, however, Baltimore had come to realize that inefficient management by his two local agents was ruining his plantation and that only his personal presence and direction could save it from failure. He arrived in Avalon in July and, although his stay was short, it was long enough, apparently, to convince him of the urgent need to give close attention to his Newfoundland interests. He returned there in 1628, evidently prepared to settle permanently as he brought with him his wife and all his children except his eldest son. (This was his second wife, Jane, whom he had married after the death in 1622 of his first wife, Anne, daughter of George Mynne of Hurlingfordbury, Herts., who had borne him six sons and five daughters.) He lived in considerable style, taking up residence in a substantial stone mansion, of which, in later years, Sir David Kirke was to be another distinguished occupant.

England and France were at war in 1628 – the year of Buckingham’s ill-fated expedition to the Isle of Rhé – and much of Baltimore’s energy, during his stay at Ferryland from the spring of 1628 to the fall of 1629, was occupied in repulsing the French privateers that were preying upon English fishing vessels in the harbours of Avalon. Shortly after Baltimore’s arrival at Ferryland, “de la Rade, of Dieppe” (probably Raymond de La Ralde), with three French ships, attacked the nearby harbour of Cape Broyle, capturing two English fishing craft in the port. Baltimore immediately ordered two men-of-war to the scene, rescued the two English vessels, and forced La Rade to flee northward leaving behind 67 members of his crew as prisoners. Baltimore’s ships set off in hot pursuit but, being outdistanced by the French, had to abandon the chase. In retaliation, Baltimore descended on six French fishing craft which had put in at Trepassey, some 50 miles south of Ferryland, captured them all and sent them to England as prizes together with their cargoes of codfish and cod oil. The prizes, incidentally, were the cause of a dispute between himself and the English merchants whose ships had assisted in the seizure, a dispute in which Baltimore with characteristic shrewdness sought to strengthen his case by having his letters of marque antedated. Profiting from his experience of French raids, Baltimore requested Charles I to despatch two warships to guard the coast of Avalon; only one ship, however, the St. Claude, was sent out, under the command of Leonard Calvert (1606–47), Baltimore’s second son, who later acted as the first governor of Maryland for his brother Cecil Calvert, the first proprietor.

Baltimore was plagued also by the opposition of some of the colonists to his policy of religious toleration. They resented the presence of the Roman Catholic priests whom he had brought out from England. The leader of the malcontents, Erasmus Stourton, a puritan clergyman, was banished by Baltimore for attempting to prevent the illegal celebration of mass in the colony. On his return to England, Stourton promptly denounced Baltimore to the authorities, but, apparently, without effect.

French raids, sectarian bickerings, and, above all, the severity of the winter climate decided Baltimore to abandon his infant colony. On 19 Aug. 1629, he wrote to the king from Ferryland, complaining that the winter lasted from October to May, that half his company of 100 were sick and that 10 of them were dead. He went on to petition Charles for a grant of land in Virginia, to which he could transfer some 40 of his settlers from Avalon. Without waiting for a reply to this appeal, he left for Virginia, whither his wife had preceded him in the fall of 1628. At Jamestown he was confronted with a requirement that he take the oaths of allegiance and supremacy as a condition of establishing himself there and so he returned to England. In 1632, he was given the territory north of the Potomac River, which became the province of Maryland, but he died before receiving the charter for Maryland, which was granted to his son, Cecil.

The Calvert family continued its interest in Newfoundland for several years. Cecil Calvert appointed William Hill as his deputy governor of Ferryland in 1634 and strongly protested the grant of Ferryland to Sir David Kirke in 1637. Following the Restoration he succeeded in securing recognition of the validity of his father’s Avalon charter of 1623.

Genuinely interested in colonization, Baltimore lacked the determination needed to triumph over the privations of the pioneer. Too easily discouraged by adversity, he had no lasting influence on the history of Newfoundland.

For the land purchased from Vaughan see John Mason’s map in William Vaughan, Cabrensium Caroleia (London, 1625; another issue, 1630); the enlargement by royal charter in 1623 is in PRO, C.O. 1/2, 23. Baltimore’s will is in Somerset House, P.C.C. 39 Audley. Other contemporary sources are: PRO, C.O.1/4, 1/5; CSP, Col., 1574–1660. William Vaughan [Orpheus Junior, pseud.], The golden fleece (London, 1626); The Newlanders cure (London, 1630). Richard Whitbourne, A discourse containing a loving invitation . . . (London, 1622). Edward Winne [Wynne], A letter to Sir George Calvert ([London?], 1621). DAB. DNB. J. P. Kennedy, Discourse on the life and character of Sir G. Calvert (Baltimore, 1845). Prowse, History of Nfld. L. D. Scisco, “Calvert’s proceedings against Kirke,” CHR, VIII (1927), 132–36.

Cite This Article

Allan M. Fraser, “CALVERT, GEORGE, 1st Baron BALTIMORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/calvert_george_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/calvert_george_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Allan M. Fraser |

| Title of Article: | CALVERT, GEORGE, 1st Baron BALTIMORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |