![<div title='Illustration gratuite pour une utilisation dans un contexte éducatif seulement et avec mention de la source originale « Vidéanthrop ». Il est interdit d'utiliser cette création à des fins commerciales, de la modifier, de la transformer ou de l'adapter. Par « contexte éducatif », nous entendons toute utilisation par un enseignant, un intervenant du monde scolaire ou un élève, pour des notes de cours, une situation d’apprentissage, la réalisation d’un site web ou tous autres travaux scolaires.'class='image-licence'><span id='bleu'></span></div>[Cérémonie de la signature du traité de la Grande Paix de Montréal en 1701 ] © <a href= Original title: Cérémonie de la signature du traité de la Grande Paix de Montréal en 1701](/bioimages/w600.537.jpg) Vidéanthrop.">

Vidéanthrop.">

Source: Link

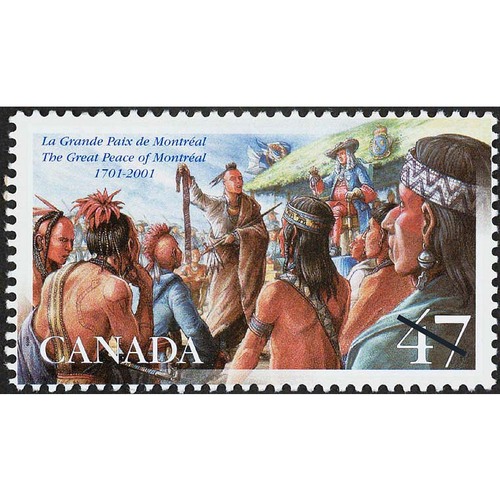

KONDIARONK (Gaspar Soiaga, Souoias, Sastaretsi), known by the French as “Le Rat”; a Tionontati or Petun Huron chief at Michilimackinac; b. c. 1649; d. 2 Aug. 1701 in Montreal, when participating in peace negotiations between the tribes of the Upper Lakes and the Iroquois.

Following the Iroquois dispersal of the Hurons in 1649, the Tionontati eventually settled at Michilimackinac, the home of several Algonkian tribes. Because they were culturally and linguistically different, the Hurons did not readily integrate with the Algonkian community, being visibly separated from the Kiskakon [Ottawa] village by a thin palisade. Although they were nominally allies of the Algonkians and traded maize to the hunting and fishing bands that gathered at the straits, the Tionontati were ready to make friendly overtures to the Iroquois if they felt their security threatened. Their immediate fear was that the latter, currently warring with the Miamis and the Illinois to the south in an attempt to gain new beaver grounds, would turn their attention to the tribes at the Straits of Mackinac.

A crisis came soon enough. While raiding westward a Seneca leader strayed, was captured by some Winnebagos, and was carried as prize to Michilimackinac. During a meeting with Henri Tonty in a Kiskakon wigwam the Seneca was murdered by an Illinois. Lest the Iroquois annihilate them, the Mackinac tribes sought the protection of the French governor and it was during negotiations with Louis de Buade* de Frontenac in 1682 that Kondiaronk first was noticed.

While the Ottawa speaker whined that they were like dead men and prayed that their father take pity on them, the Rat acknowledged “that the earth was turned upside down,” and reminded Frontenac that the Huron, his erstwhile brother, “is now thy son” and therefore entitled to protection in return for obedience. These blandishments neither convinced Frontenac nor satisfied the Kiskakons, for it was known that the Hurons had sent wampum belts to the Iroquois without confiding in the allies or giving notice to Onontio [the governor]. On being questioned, Kondiaronk claimed that the Huron action had been an attempt to settle the affair of the murdered warrior but the Kiskakons maintained that not only had the Hurons withheld the wampum belts of the Ottawas but they had blamed them for the entire incident. Having trusted the Hurons to placate the Senecas on their behalf, the Ottawas now feared unilateral dealing at their expense.

In spite of Frontenac’s efforts to get them to trust one another, both tribes returned to Michilimackinac as uneasy neighbours while Iroquois aggression against the western tribes continued unabated. In 1687 after Jacques-René Brisay de Denonville’s invasion of the Seneca country, Kondiaronk and the allies extracted from him, in return for their loyalty, a pledge that the war should not be terminated until the Iroquois were destroyed. Peace might suit the old men of the Iroquois and relieve a harassed French colony, but it posed a threat to the Hurons of Michilimackinac that Kondiaronk perceived. Without the French to divert their attention, the Iroquois would be able to concentrate on their campaigns in the west. In the summer of 1688 Kondiaronk decided to strike a blow for himself. He raised a war party and they set out to take scalps and prisoners.

Arriving at Fort Frontenac (Cataracoui, now Kingston, Ont.) to obtain information, Kondiaronk was amazed to learn from the commander that Denonville was negotiating a peace with the Five Nations, whose ambassadors were momentarily expected there for conduct to Montreal. He was advised to return home at once and to this he assented. Inwardly resenting the French decision, however, Kondiaronk withdrew across the lake to Anse de la Famine (Mexico Bay, near Oswego) where he knew the Onondaga embassy must pass before going on to the fort. Within a week the delegation appeared, composed of four councillors and 40 escorting warriors. The Hurons waited until they began to land and greeted them with a volley as they disembarked. In the confusion, a chief was killed, others were wounded and the rest were taken prisoner.

The captives were no sooner tied securely than Kondiaronk opened a fateful woods-edge council. He represented that he had acted on learning from Denonville that an Iroquois war party would soon pass that way. The chagrined Iroquois, through their chief ambassador, the noted Teganissorens, protested that they were peace envoys voyaging to Montreal. Kondiaronk feigned amazement, then rage and fury, cursing Denonville for betraying him into becoming an instrument of treachery. Then he addressed his prisoners and Teganissorens: “Go, my brothers, I release you and send you back to your people, despite the fact we are at war with you. It is the governor of the French who has made me commit this act, which is so treacherous that I shall never forgive myself for it if your Five Nations do not take their righteous vengeance.” When he propped up his words with a present of guns, powder, and balls, the Iroquois were convinced, assuring him on the spot that if the Hurons wanted a separate peace they could have it. As Kondiaronk had lost a man, however, custom entitled him to request a replacement for adoption: the Onondagas gave him an adopted Shawnee. They then turned back to their villages and the Hurons set out for Michilimackinac. Passing by Fort Frontenac Kondiaronk called on the commandant, and made this chilling boast as he left: “I have just killed the peace; we shall see how Onontio will get out of this business.”

The war party reached Michilimackinac in apparent triumph and presented the hapless “Iroquois” to the commandant who, having heard nothing of the intended peace between his government and the Iroquois, promptly condemned the man to be shot. Although the captive protested that this treatment was a violation of diplomatic immunity, Kondiaronk pretended that the man was light-headed and, even worse, afraid to die. Kondiaronk sent for an old Seneca slave to witness the execution, told him his countryman’s story, and freed him to carry the word back to the Iroquois. Kondiaronk charged him to relate how badly the French abused the custom of adoption, and how they violated their trust while deceiving the Five Nations with feigned peace negotiations.

Although one member of the Iroquois delegation attacked by Kondiaronk had escaped to Fort Frontenac where the French gave assurances of their innocence in the affair, the damage done to the peace negotiations was irreparable. The message of French perfidy passed rapidly from fire to fire the length of the Iroquois longhouse. The wampum belts were buried and the war kettles hung. Within a year of Kondiaronk’s treachery the war parties of the Five Nations descended on the Island of Montreal, sacking Lachine in the summer of 1689. Because of the renewal of French-English hostilities in Europe, the New York colony aided and abetted the Indian attacks but Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan, held the Rat responsible for provoking the Iroquois to the point where it was impossible to appease them.

In the decade of warfare that followed, Kondiaronk’s intrigues were numerous. In 1689 he was caught plotting with the Iroquois for the destruction of his Ottawa neighbours and that September, as if to witness his own mischief, he came down to Montreal and returned home unscathed, proving that the French lacked the temerity to hang him. But he was worth more alive than dead. Although it was probably he who was behind the Ottawas’ rebuff to Frontenac the following year and their proposed treaty with the Iroquois to trade at Albany, by mid-decade when the Hurons at Michilimackinac were again divided Kondiaronk was leading the pro-French faction with another Huron chief, Le Baron, leading the English-Iroquois opposition, each side having a mixed following of Ottawas. The Baron wanted to ally with the Iroquois to destroy the Miamis, but in 1697 the Rat warned the latter and attacked the former, cutting 55 Iroquois to pieces in a two-hour canoe engagement on Lake Erie. This victory ruined the possibility of a Huron-Iroquois alliance, re-established Kondiaronk’s pre-eminence, and helped to restore the tribes at Michilimackinac as children of Frontenac when they came to Montreal to council.

With the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 ending the conflict in Europe, New York and New France agreed to suspend hostilities. The withdrawal of active English support, combined with the depredations of a long war, prompted the Iroquois to make peace overtures to Frontenac. Negotiations went on for several years and led to the settlement of 1701. Kondiaronk was present whenever the allies conferred. At one of the initial meetings between Frontenac and the Ottawas over a truce with the Iroquois, a Cayuga delegate tried to embarrass the Ottawas by accusing them of having negotiated without the participation of Onontio. Kondiaronk, “the most civilized and considerable person of the Upper Nations,” rebuked the Cayuga: “We are in the presence of our father; nothing should be concealed from him, so relate the message carried in the wampum belts that you first addressed to us and to the Ottawas.” The discomfited Cayuga declined the challenge.

After Frontenac died, the Rat transferred his respect to Louis-Hector de Callière, the new Onontio. In 1700 Callière brought the various tribes together at Montreal to achieve a brittle armistice preparatory to the final settlement. On this occasion the Rat urged the Iroquois to listen to the voice of their father: “Let it not be in a forced or insincere way that you ask him for peace; for my part I return to him the hatchet he had given me, and lay it at his feet. Who will be so bold as to take it up? “ For a while the sparks flew thickly on both sides. The Iroquois speaker, having listened calmly to the Rat, replied with spirit: “Onontio had hurled the hatchet into the sky [made war] and what is up there never comes down again; but there was a little string attached to this hatchet by which he pulled it back, and struck us with it. . . .” Here the Rat took charge to remind them that “the Seneca was planning the complete destruction of the French, intending not even to spare his father [Frontenac], whom he intended to put first into the kettle, for an Iroquois threatened to drink his blood from his skull . . .” Kondiaronk said further of the Iroquois “that their hands were covered with the blood of our allies, that the allies’ flesh was even still between their teeth, that their lips were all gory with it, [and] it was well known that they were lying to hide what was in their hearts.” In the Rat’s style, one must dissipate the clouds shrouding the Tree of Peace.

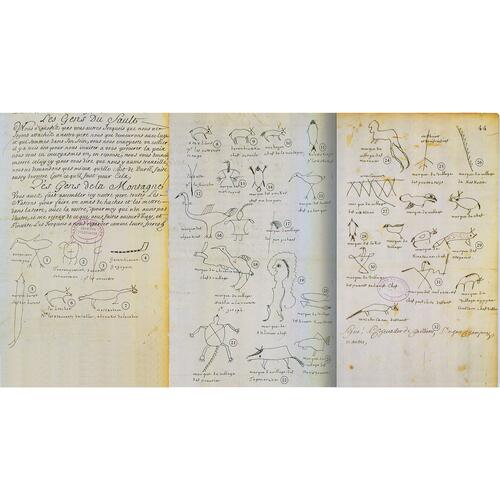

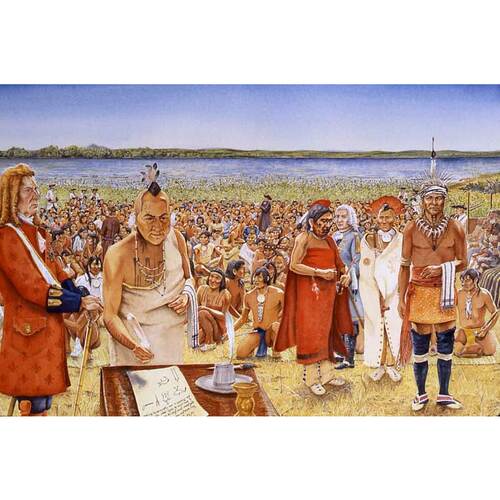

The final Indian congress was held the following year. It began 21 July 1701, when Bacqueville de La Potherie [Le Roy], the prime source on the proceedings, went to meet the delegates at the village of the Mission Indians at Sault-Saint-Louis (Caughnawaga). The first flotilla to appear consisted of 200 Iroquois, headed by the ambassadors of the Onondagas, Oneidas, and Cayugas, the Senecas having dropped by the way, and the Mohawks following later. They approached firing their guns and the salute was returned by their brethren, the mission Indians, ranged along the shore. They were properly greeted at the water’s edge by a small-fire and then led by the arm to the main council lodge where they smoked for a quarter of an hour with great composure. Next they were greeted with the “three rare words” of the ritual of requickening – wiping of tears, clearing the ears, and opening the throat – to prepare them to speak of peace the next day with Onontio.

The protocol of forest diplomacy demanded the use of metaphor, timing, manipulation of space, and reciprocal action by both parties. The kettle, the hatchet, the road, the fire, the mat, the sun, and the Tree of Peace were each subject to qualifiers appropriate to the mood or intent. Leading or receiving a procession at the woods-edge, taking guests by the arm to the main fire, arranging the council grounds, seating delegates, allowing them to withdraw to consider, and to return to reply, were part of the spatial arrangements. Wiping away tears, exchanging speeches and songs, passing the pipe, throwing wampum belts, returning prisoners, distributing presents, and apportioning the feast were expected of both hosts and guests. All of this belonged to a ritual widely shared in the lower lakes by Iroquoians and Algonkians alike, and surviving as a fragment in the Iroquois Condolence Council.

The following day the Iroquois shot the rapids to the main fire at Montreal, where they were greeted by the crash of artillery. The smoke of their feasting had scarcely disappeared when in their wake came 200 canoes of the French allies – Chippewas, Ottawas, Potawatomis, Hurons, Miamis, Winnebagos, Menominees, Sauks, Foxes, and Mascoutens – over 700 Indians to be received ceremoniously at the landing. The Far Indians performed their specialty, the Calumet Dance, to the accompaniment of gourd rattles, making friends of their hosts. By 25 July negotiations between the tribes were fully under way and the Rat spoke of the difficulties encountered in recovering Iroquois prisoners from the allies. He wondered whether the Iroquois would comply in an exchange with sincerity or cheat them of their nephews taken in the past 13 years of war. He suspected that the allies were to be deceived, although they were still willing to leave their prisoners as a gesture of good faith. The next day, however, the Iroquois admitted that they did not have the promised prisoners, saying that as small children they had been given to families for adoption and professing not to be masters of their young people. This excuse annoyed the Hurons and Miamis who had forcibly taken the Iroquois captives away from foster families. Days of wrangling followed.

The Rat, having persuaded his own and allied tribes to bring their Iroquois prisoners to Montreal, was deeply humiliated at being duped, and shortly afterwards succumbed to a violent fever. He came so ill to a council held 1 August to discuss the matter that he could not stand. Yet everyone was glad when he spoke: “He sat down first on a folding stool; [then] a large and comfortable armchair was brought for him so that he could speak with greater ease; he was given some wine to strengthen him but he asked for a herbal drink and it was realized that he wanted syrup of maiden-hair fern,” a sovereign Iroquois remedy. Having recovered somewhat, he spoke in a languid tone while the assembly listened intently for nearly two hours, occasionally voicing its approval of his points. Though he was obviously chagrined at the conduct of the Iroquois, his political skill made him take a new tack, and he reviewed at length his own diplomatic role in averting attacks on the Iroquois, in persuading reluctant tribal delegations to come to Montreal, and in recovering prisoners. “We could not help but be touched,” wrote La Potherie, “by the eloquence with which he expressed himself, and [could not fail] to recognize at the same time that he was a man of worth.” After speaking the Rat felt too weak to return to his hut, and was carried in the armchair to the hospital, where his illness steadily worsened. He died at two a.m.

The Iroquois, who love funerals, came to cover the dead. Sixty strong, they marched in solemn procession with great dignity, led by Chabert de Joncaire, with Tonatakout, the leading Seneca chief, walking at the rear and weeping. When close to the body, they sat in a circle around it, while the appointed chanter continued pacing for a quarter of an hour. He was followed by a second speaker, Aouenano, who wiped away the tears, opened the throat, and poured in a sweet medicine to re-quicken the mourners. Then producing a belt, he restored the Sun, urging the warriors to emerge from darkness to the light of peace. He then temporarily covered the body pending the main rites. There were similar gestures by other tribal delegations.

The Rat’s funeral was held the following day (3 Aug. 1701). The French wished the Hurons and their allies to know how touched they were by the loss of so considerable a person. Pierre de Saint-Ours headed a military escort of 60 men, followed by 16 Huron warriors in ranks of 4 wearing beaver robes, faces blackened as a mark of their mourning, and guns reversed; then came clergy and 6 war chiefs bearing the flower-covered coffin on which lay a plumed hat, a sword, and a gorget. Behind the train were the brother and sons of the dead chief, and files of Huron and Ottawa warriors. Madame de Champigny, attended by Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, governor of Montreal, and staff officers closed the procession. After the Christian burial service – for the Rat was a convert of the Jesuits – the soldiers and warriors fired two volleys of musketry, one for each of the two cultures represented in the rites. Then each man in passing fired his musket a third time. Kondiaronk was interred in the church of Montreal and his tomb was inscribed: “Here lies the Rat, Huron Chief.”

Today no trace of Kondiaronk’s grave remains. He lies somewhere near or beneath Montreal’s Place d’Armes.

Charlevoix, History (Shea). Indian tribes (Blair). The Iroquois book of rites, ed. Horatio Hale (Toronto, 1963). Lahontan, New voyages (Thwaites). La Poterie, Histoire (1722). NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), X. W. N. Fenton, The roll call of the Iroquois chiefs; a study of a mnemonic cane from the Six Nations reserve (Washington, 1950). Kathleen Jenkins, Montreal, island city of the St. Lawrence (Garden City, N.Y., 1966). W. V. Kinietz, The Indians of the western Great Lakes, 1615-1760 (Ann Arbor, 1940). Parkman, Count Frontenac and New France (1891). W. N. Fenton, “An Iroquois condolence council for installing Cayuga chiefs in 1945,” Washington Academy of Sciences J., XXXVI (1946), 112–27. A. F. C. Wallace, “Origins of Iroquois neutrality: The grand settlement of 1701,” Pennsylvania History, XXIV (1957), 223–35.

Cite This Article

William N. Fenton, “KONDIARONK (Gaspar Soiaga, Souoias, Sastaretsi) (Le Rat),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kondiaronk_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kondiaronk_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | William N. Fenton |

| Title of Article: | KONDIARONK (Gaspar Soiaga, Souoias, Sastaretsi) (Le Rat) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |