As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

EDA’NSA (Edensa, Edensaw, Edenshaw, Edinsa, Edinso, Idinsaw, meaning “melting ice from a glacier” from the Tlingit word for “wasting away”; Gwai-Gu-unlthin, meaning “the man who rests his head on an island”; Captain Douglas; baptized Albert Edward Edenshaw), Haida chief, trader, and pilot; b. c. 1810 in Gatlinskun Village, near Cape Ball on Graham Island, Queen Charlotte Islands (B.C.), son of Duncan and Ninasinlahelawas; m. first Ga’wu aw, the widow of his uncle Chief Edinsa, and they had a son, Ga’wu (later George Cowhoe); m. secondly Amy, the niece of his first wife, and they had a son, Henry Edenshaw; d. 16 Nov. 1894 in Masset, B.C.

The man who would become the dynamic and enigmatic native leader Eda’nsa was given the name Gwai-Gu-unlthin at birth. Legend holds that his ancestors came to the Queen Charlotte Islands from the Stikine River area. Throughout his lifetime he endeavoured to identify himself with a chiefly title dating from the early contact of the Haidas with Europeans. In 1878 he testified that his hereditary title descended from Chief Blakow-Coneehaw, who had met Captain William Douglas in 1788 and exchanged names with him to secure a trade alliance; he thus also called himself Captain Douglas. He is reported to have claimed to be associated by name or even related to Governor James Douglas*. He was by ancestry third in line to the great Haida Eagle chiefship of the Sta Stas Shongalth lineage, which descended, by matrilineal succession, from his uncle Edinsa to his cousin Yatza and then, in 1841, to him.

Now Eda’nsa in name, he set about, as was customary, demonstrating his identity. The Sta Stas headed by Eda’nsa were one of the three related lineages that vied for control of the ancient Eagle town of Kiusta on Graham Island, the other two being the Sta Stas originally from the village of Hiellen and the Q’awas, whose head, Itine, was town chief. Oral testimony indicates that when Itine died in the early 1840s, Eda’nsa took advantage of his rank as head of the senior lineage. He arrived at Kiusta with his people, built the huge Story House, and gave a potlatch, thus demonstrating his suitability as heir to the town chiefship. Kiusta passed to the Sta Stas and Eda’nsa claimed to be its “rightful chief.” All “high ranks” were trained from childhood to act in this way, but Eda’nsa seems to have been particularly anxious to become, as he later claimed, “the greatest chief of all the Haidas.” His method of acquisition was not, however, universally admired by his people.

Eda’nsa engaged in the coastal trade in Indian slaves, acquired by the natives from neighbouring native peoples by raid or barter. By 1850 he possessed twelve slaves, and he received ten more from his bride’s father when he married Ga’wu aw, a high-ranking Haida woman, about 15 years his senior, from Kaigani (Alaska). Their union suggests a marriage to promote his power, wealth, and prestige. When officers of the Royal Navy encountered him in the early 1850s they had no doubt as to his position of influence.

In September 1852 Eda’nsa was hired as pilot for the schooner Susan Sturgis, which, under the command of Matthew Rooney, was trading in the Queen Charlotte Islands. Eda’nsa knew local waters intimately and was constantly in demand among visiting masters. Ships in the area faced not only navigational dangers, however, but also raids by the Haidas, who were known to plunder vessels in difficulty. The Susan Sturgis sailed from Skidegate, on the southeast coast of Graham Island, for Kung, a village at the narrows leading to Naden Harbour, Graham Island, to which Eda’nsa was moving. Near Rose Spit some Massets, led by Chief Weah, boarded the schooner, imprisoned the white men, pillaged the strong-box, and burned the vessel. Indian testimony at a subsequent investigation by the Royal Navy suggested that Eda’nsa had told Weah of the schooner’s lack of defences. Captain Augustus Leopold Kuper of the Thetis believed that the chief had “shared in the plunder.” Eda’nsa’s complicity was never proved, however, and the chief, in fact, claimed to have saved the white men from being murdered. They were released when Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor John Work* paid a ransom.

Captain Wallace Houstoun of the Trincomalee considered Eda’nsa “a man of great influence in the neighbourhood and one worth treating with every consideration.” Captain James Charles Prevost of the Virago, on which the chief had been detained for questioning, thought him “decidedly the most advanced Indian I have met on the Coast: quick, cunning, ambitious, crafty, and, above all, anxious to obtain the good opinion of the white men.” The most thorough assessment of Eda’nsa was given by the Virago’s paymaster, William Henry Hills, who wrote: “He would make a Peter the Great, or Napoleon, with their opportunities. . . . He has great good sense and judgement, very quick, and is subtle and cunning as the serpent. . . . He is ambitious and leaves no stone unturned to increase his power and property.” Hills also noted that Eda’nsa spoke “very intelligible English.” He stood “about 5 feet 7 ins., with a shade of yellow in his complexion, hazel eyes rather small, and broad features. Square and high shoulders and a wiry form. Wears his hair in European style, and whenever we saw him was always dressed neatly.”

In his search for increased trade, especially with vessels on the Alaska and northern British Columbia coasts, Eda’nsa had built two villages: Kung, or “dream town,” established probably in 1853 (abandoned by 1884), and Yatza, founded around 1870 on the north coast of Graham Island. Although the latter site was more exposed to the environment, it was more accessible to trade than Kung and Eda’nsa settled there before moving to Masset, probably in the 1870s or 1880s. During this period the Haidas, whose population had been reduced by smallpox and other diseases from some 6,000 in the late 1830s to about 900 by 1880, were rapidly abandoning smaller villages for Masset and Skidegate; they were attracted to these locations by the activities of Anglican missionaries at Masset and Methodist ones at Skidegate.

In later years Eda’nsa competed with Chief Weah for pre-eminence at Masset. The two chiefs, baptized by Anglican minister Charles Harrison in 1884, were among the first Haidas to become Christians. Eda’nsa adopted as his Christian name Albert Edward, after the Prince of Wales, and he was confirmed by Bishop William Ridley. At this point information about Eda’nsa becomes fragmentary. Glimpses of him occur in the anthropological writings of James Gilchrist Swan, who, in 1883, hired him as a guide and pilot. Newton Henry Chittenden of the British Columbia exploratory expedition met him in 1884 and reported, “He has succeeded one after another of the chiefs of various parts of the group by virtue of the erection of carved poles to their memory, bountiful feasts and generous potlatches to their people, until he is now recognized as their greatest chief.” Eda’nsa died in 1894, predeceased by four years by his son George Cowhoe, the first native teacher on the Queen Charlotte Islands. His title or titles passed to a nephew, Tahaygen (baptized Charlie Edenshaw*), the celebrated Haida artist.

It is doubtful whether Eda’nsa was in fact the greatest of Haida chiefs; certainly he wanted to be, and he told credulous white men that he was. His life spanned the era of colonization and rampant disease among the Haidas, and he endeavoured, in the face of great structural and economic transformations among his people, to maintain and enhance his position. His achievements illustrate Haida adaptability to changing circumstances. Eda’nsa deserves to be seen as an energetic and powerful man, moved by inner forces, perhaps even by insecurities, to establish his own greatness within the framework of Haida social structure, ever mindful, it seems, of the white man’s influence and commercial advantage.

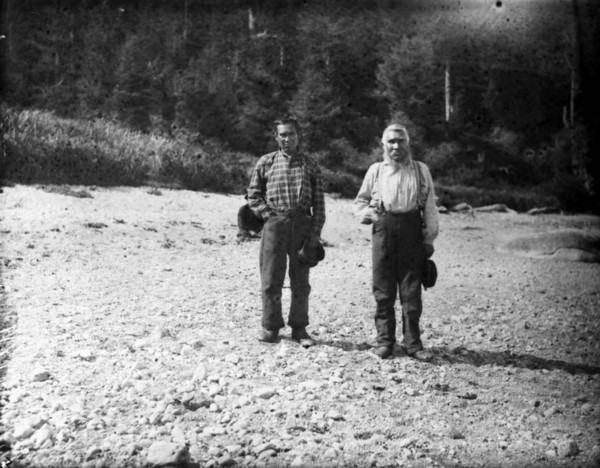

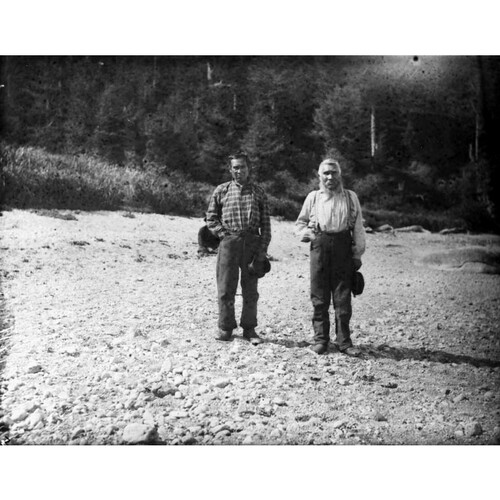

A photograph of Eda’nsa held by the National Museums of Canada (Ottawa), neg.266, is reproduced in B. M. Gough, Gunboat frontier (cited below), plate 16.

Mitchell Library (Sydney, Australia), mss 1436/1 (W. H. Hills, “Journal on board H.M.S. Portland and H.M.S. Virago, 8 Aug. 1852–8 July 1853”) (mfm. at Univ. of B.C. Library, Special Coll., Vancouver). NA, MG 24, F40. PABC, G.B., Admiralty corr., I, Merivale to Admiralty, 13 May 1852; Stafford to Moresby, 24 June 1852; Add. mss 757; Add. mss 805; OA 20.5 T731 H. PRO, ADM 1/ 5630, esp. J. C. Prevost, report to Fairfax Moresby, 23 July 1853, enclosure in Moresby to secretary of the Admiralty, 13 Oct. 1853. N. H. Chittenden, Exploration of the Queen Charlotte Islands (Victoria, 1884; repr. Vancouver, 1984). G. M. Dawson, Report on the Queen Charlotte Islands, 1878 (Montreal, 1880), app.A. “Four letters relating to the cruise of the ‘Thetis,’ 1852–53,” ed. W. K. Lamb, BCHQ, 6 (1942): 200–3. [J. C. Prevost], “Account of the plunder of the Susan Sturgis, American schooner, burnt at Queen Charlotte Islands,” Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle (London), 23 (1854): 209–12. J. G. Swan, The northwest coast; or, three years’ residence in Washington Territory (New York, 1857). Walbran, B.C. coast names, 162–63. M. B. Blackman, During my time: Florence Edenshaw Davidson, a Haida woman (Seattle, Wash., and London, 1982); Window on the past: the photographic ethnohistory of the northern and Kaigani Haida (National Museum of Man, Mercury ser., Canadian Ethnology Service paper no.74, Ottawa, 1981). J. H. van den Brink, The Haida Indians: cultural change mainly between 1876–1970 (Leiden, Netherlands, 1974). Douglas Cole, Captured heritage: the scramble for northwest coast artifacts (Vancouver and Toronto, 1985). W. H. Collison, In the wake of the war canoe . . . (London, 1915). K. E. Dalzell, The Queen Charlotte Islands, 1774–1966 (Terrace, B.C., 1968); The Queen Charlotte Islands, book 2, of places and names (Prince Rupert, B.C., 1973). R. [A.] Fisher, Contact and conflict: Indian-European relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890 (Vancouver, 1977). B. M. Gough, Gunboat frontier: British maritime authority and northwest coast Indians, 1846–1890 (Vancouver, 1984); “Haida-European encounter, 1774–1900: the Queen Charlotte Islands,” Outer shores, ed. Nicholas Gessler (forthcoming). Charles Harrison, Ancient warriors of the north Pacific: the Haidas, their laws, customs and legends, with some historical account of the Queen Charlotte Islands (London, 1925). M. L. Stearns, Haida culture in custody: the Masset band (Seattle, 1981); “Succession to chiefship in Haida society,” The Tsimshian and their neighbors of the north Pacific coast, ed. Jay Miller and C. M. Eastman (Seattle and London, 1984), 190–219. J. R. Swanton, Contributions to the ethnology of the Haida (Leiden and New York, 1905; repr. New York, [1975]). B. M. Gough, “New light on Haida chiefship: the case of Edenshaw, 1850–1853,” Ethnohistory (Lubbock, Tex.), 29 (1982): 131–39; “The records of the Royal Navy’s Pacific Station,” Journal of Pacific Hist. (Canberra, Australia), 5 (1969): 146–53.

Cite This Article

Barry M. Gough, “EDA’NSA (Edensa, Edensaw, Edenshaw, Edinsa, Edinso, Idinsaw, Gwai-Gu-unlthin, Captain Douglas) (baptized Albert Edward Edenshaw),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eda_nsa_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eda_nsa_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry M. Gough |

| Title of Article: | EDA’NSA (Edensa, Edensaw, Edenshaw, Edinsa, Edinso, Idinsaw, Gwai-Gu-unlthin, Captain Douglas) (baptized Albert Edward Edenshaw) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |