Source: Link

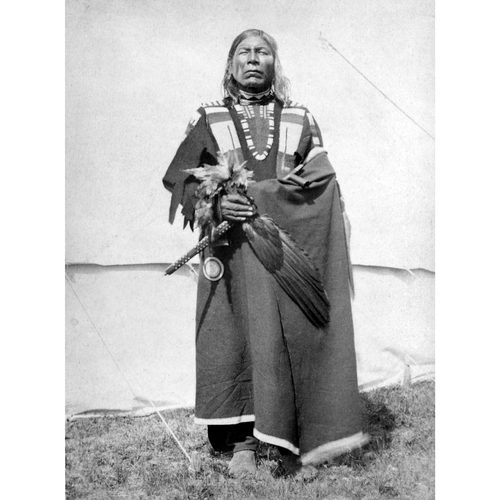

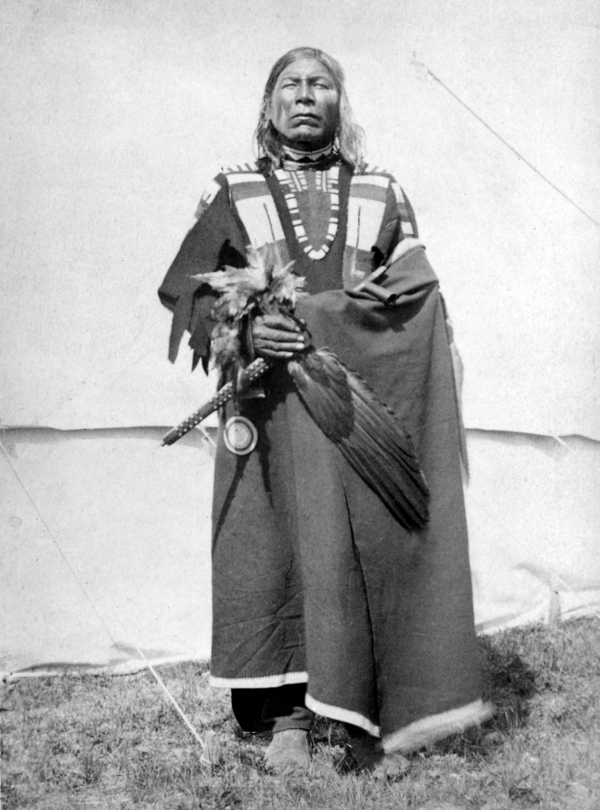

PASKWĀW (Pasquah, Pisqua, The Plain, known in French as Les Prairies, literally “it is a prairie”), Plains Cree and chief of a band of Plains Saulteaux; b. c. 1828; d. 15 March 1889 on his reserve near Fort Qu’Appelle (Sask.).

Paskwāw was said to have been the son of Mahkesīs (Mahkaysis), a prominent chief of the Plains Cree who died in 1872. Prior to 1874, Paskwāw and his band lived near Leech Lake (Sask.) where they had a few houses, gardens, and a small herd of cattle. In spite of their unusual, if meagre, efforts at agriculture, the members of the band depended primarily on the buffalo hunt, small game, and fish for their livelihood.

Paskwāw attended the negotiation of Treaty no.4 at Fort Qu’Appelle in September 1874, which brought together all the Plains Indians of what is now southern Saskatchewan. The terms of the treaty called for a cession of all Indian rights to the land in that area and a promise by the Indians to obey Canadian laws. In return, the Indians were offered a gratuity of $7 and an annuity of $5 for each band member, $15 for each headman, and $25 for each chief. They were promised a reserve of one square mile for every five Indians, the maintenance of a school on each reserve, certain farm implements, livestock, and other benefits. Each chief and headman was to receive a treaty medal and a suit of clothing every three years. Paskwāw’s only recorded contribution to the discussion of these terms concerned the sale of Rupert’s Land to Canada by the Hudson’s Bay Company. He argued that the land belonged to the Indians and that the £300,000 paid to the HBC should have been given to them. In spite of the firm refusal of the Canadian representatives [see Alexander Morris] to consider this demand, Paskwāw signed the treaty.

The following year the Indian Department officials returned to Fort Qu’Appelle to pay the annuities and to distribute some of the articles due under the terms of the treaty. They found that Paskwāw’s was the only band ready to receive its cattle and oxen. At this time he stated that he wished to have his reserve at Leech Lake, where the band had been residing. Surveyor William Wagner* was instructed to lay out the required amount of land, but Paskwāw began to vacillate. He remained near Fort Qu’Appelle and attempted to persuade other chiefs to join in refusing to have their reserves surveyed. Paskwāw apparently felt that if he allowed land to be surveyed for his band, he would be submitting to the domination of the whites. But in 1876 Indian agent Angus McKay* was able to persuade the chief to permit Wagner to lay out a reserve of 57 square miles about five miles west of Fort Qu’Appelle.

Paskwāw and his band settled on this reserve, but his intrigues did not end. In the spring of 1878 he journeyed to Winnipeg, for an interview with Lieutenant Governor Joseph-Édouard Cauchon of Manitoba. The chief complained that food and building materials promised to him had not been delivered. He also declared that there was much unrest among the Plains Indians which could be alleviated if the government were to provide him with enough food and tobacco to hold a great feast for all these Indians, at which he would speak in favour of the Canadian government’s policies. Indian Department officials interpreted this suggestion as a scheme by Paskwāw to increase his personal influence with other bands, and denied that food or building supplies had ever been promised him. In 1882 Paskwāw headed a movement of the Indians in the Fort Qu’Appelle area against the government’s policy of paying annuities to each band on its own reserve, rather than at a mass gathering at Fort Qu’Appelle. The Indian Department officials alleged that the Indians wished to be paid their annuities at large assemblies in order to intimidate the small party of officials, forcing them to distribute more provisions and to make more promises than the government thought desirable. Paskwāw had initially declared that he would not take his money but quickly capitulated on discovering that his own band would not support him.

The return of Chief Piapot [Payipwat*] from the Cypress Hills in 1883 and his agitation for better terms for the Indians of Treaty no.4 brought renewed tension to the Qu’Appelle district. Paskwāw apparently supported Piapot’s agitation but, entirely dependent upon the government for enough food to prevent starvation, he did not make this support explicit. In the spring of 1884 a false report of fighting between the North-West Mounted Police and a group of Piapot’s followers startled the members of Paskwāw’s band into hasty preparations for an armed clash with the authorities. Apart from this incident, Indian Department officials found little cause for concern with Paskwāw’s band during the tense months preceding the North-West rebellion. When the uprising occurred in the spring of 1885 [see Louis Riel], Paskwāw, together with Chief Maskawpistam (Muscowpetung) of the adjacent reserve, dispatched a telegram to Sir John A. Macdonald* proclaiming their loyalty and denouncing the insurrectionists to the north. The prime minister read the telegram in the House of Commons, and in reply to the chiefs promised that they would be well treated.

Paskwāw died of tuberculosis on 15 March 1889, after suffering from the disease for several years. Indian Agent John Bean Lash, who believed that the tribal system was a hindrance to Indian progress, successfully prevented the selection of a successor. In spite of the standing of Mahkesīs, his reputed father, Paskwāw had little influence beyond his own band. Well known for his intrigues, he succeeded only in annoying, not alarming, the Canadian government. In contrast to the actions of such other chiefs as Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa], his protests were short-sighted and his demands usually trivial.

PAC, RG 10, 133, 3582, file 889; 3584, file 1130/3A; 3602, file 1760; 3612, file 4012; 3613, file 4013; 3625, file 5489; 3632, file 6418; 3642, file 7581; 3654, file 8904; 3665, file 10094; 3672, file 10853/1; 3682, file 12667; 3686, file 13168; 3745, file 29506/4/1; 3761, file 32248; 3815, file 56405; 3875, file 90299. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 23 April 1885. Parl., Sessional papers, 1877, VII, no.11; 1884, III, no.4; 1885, III, no.3; 1890, X, no.12. [James Carnegie], Earl of Southesk, Saskatchewan and the Rocky Mountains . . . (Toronto and Edinburgh, 1875; repr. Edmonton, 1969).

Cite This Article

Kenneth J. Tyler, “PASKWĀW (Pasquah, Pisqua) (The Plain, Les Prairies),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/paskwaw_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/paskwaw_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth J. Tyler |

| Title of Article: | PASKWĀW (Pasquah, Pisqua) (The Plain, Les Prairies) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |