![Description English: Isabella Valancy Crawford Date c1919 [22 October 2007(2007-10-22) (original upload date)] Source from Canadian singers and their songs : a collection of portraits and autograph poems. Publisher: Toronto : McClelland & Stewart [Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by User:Billinghurst using CommonsHelper.] Author Caswell, Edward S. (Edward Samuel), 1861-1938 Original uploader was YUL89YYZ at en.wikipedia Permission (Reusing this file) PD-CANADA.

Original title: Description English: Isabella Valancy Crawford Date c1919 [22 October 2007(2007-10-22) (original upload date)] Source from Canadian singers and their songs : a collection of portraits and autograph poems. Publisher: Toronto : McClelland & Stewart [Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by User:Billinghurst using CommonsHelper.] Author Caswell, Edward S. (Edward Samuel), 1861-1938 Original uploader was YUL89YYZ at en.wikipedia Permission (Reusing this file) PD-CANADA.](/bioimages/w600.4578.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CRAWFORD, ISABELLA VALANCY, author and poet: b. 25 Dec. 1850 in Dublin (Republic of Ireland), daughter of Dr Stephen Dennis Crawford and Sydney Scott; d. unmarried 12 Feb. 1887 at Toronto, Ont.

Of all the literary lives of her generation in Ontario, the life of Isabella Valancy Crawford is the most obscure. How she came to write in such a variety of styles, with such a range of subject matter, when she was isolated from fellowship with other authors is a matter of wonderment and speculation. Before 1972, when Mary F. Martin published “The short life of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” the only biographical information available was offered by John William Garvin* in his preface to The collected poems (1905). His wife Katherine Hale added to that but neither biographer verified the poet’s birthdate or origins. However, research at universities gained momentum in the 1970s. A reprint of the collected poems in 1972, with an introduction by poet James Reaney, made Crawford’s work generally available; six of her short stories, edited by Penny Petrone, appeared in 1975; and in 1977 the Borealis Press published a book of fairy stories and a long unfinished poem, “Hugh and Ion.” The poem had been discovered in the Queen’s University Archives (Kingston, Ont.) by Dorothy Livesay, who named it “The Hunter’s Twain.” She also found, in Dublin Castle Archives, a genealogy of the Crawford family from 1616, when one William Crawford left “Cunningburne,” Scotland, to settle in County Antrim (Northern Ireland). His direct descendent, Stephen Crawford, was listed as a voter in Donnybrook, Dublin, from 1836 but did not live there until 1845 (the year of his death). It is therefore possible that he also had apartments above his place of business on Grafton Street, and that his second son, Dr Stephen Dennis Crawford, may have brought his wife, Sydney Scott, to that address. No record has been found of that marriage or of the birthdates and birthplaces of at least six children, of whom Isabella wrote that she was the sixth.

Epidemics in Ireland may have led to the deaths of the first five children and to the decision to emigrate to Wisconsin. The parents’ arrival date there and whether the infant Isabella accompanied them are not as yet known. But it is certain that another daughter, Emma Naomi, was born in Wisconsin in 1854, whereas a son, Stephen Walter, was born in 1856 in Ireland. In a history of the Crawford family being written by a direct descendant of this son, Mrs Catherine Humphrey, the author propounds the theory that Mrs Crawford returned to Dublin for the birth of her son whilst the doctor went to Canada in search of a home. Penny Petrone has found in the registry office at Walkerton, Ont., a record of an 1858 transaction in Paisley, Canada West, which concerned a domicile in the name of “Mrs Sydney Crawford.”

The only existing account of Crawford’s early childhood in Paisley tells of the genteel style of living of this Scots-Irish family, a style that must have been a cover for poverty. In a letter, a neighbour of the Crawfords reports that in an outlying settlement like Paisley a doctor’s duties were largely those of midwifery, and that payment was often in kind; however, “women were afraid to have him [Dr Crawford] as he was a heavy drinker, but very clever if sober.” An anonymous account (probably emanating from one of the Strickland family) records how the family left the pioneer farming community in 1864 for the more established settlement of Douro Township: “They seemed to be very poorly off and we felt real sorry for them in Canada amidst such unsuitable surroundings. My brother, knowing that there was no resident physician in the village of Lakefield, made to them the following offer. That they move to Lakefield and make use of his home during the months in which he would be away from the village.” Lakefield was a more sophisticated community, containing as it did Samuel Strickland*’s “Farm School” for gentlemen agriculturalists. But it was his sisters, the writers Susanna Moodie [Strickland] and Catharine Parr Traill [Strickland*], who must have fascinated the young Crawfords. Mrs Traill’s daughter Katie (Katharine Agnes) is thought to have been a close companion of Isabella. Moreover the Traills had a summer cottage near a Stony Indian reserve where the young girl might have picked up her interest in Indian legends and beliefs. The image of the canoe is recurrent in Crawford’s poetry and she must have delighted in canoeing on the Otonabee River and Kawartha Lake, where the Indians hunted and fished amongst the water lilies. In direct contrast to this wilderness was the bustling market town of Peterborough, where Dr Crawford set up practice in 1869.

In the Peterborough years Crawford began sending poems and stories to newspapers which she would have found in the mechanics’ institute. The Toronto Mail was the first known publisher of a poem by Crawford, “The Vesper Star,” on 24 Dec. 1873. When Dr Crawford died, on 3 July 1875, the three women became dependent on Isabella’s literary earnings. There had been a quarterly stipend from the doctor’s youngest brother, Dr John Irwin Crawford, in Ireland, but this ceased at some time, perhaps as early as the move to Peterborough. Isabella’s only living brother, Stephen Walter, had left home at 16 to seek work in northem Ontario and, though from time to time he visited his widowed mother and apparently endeavoured to help, he married in 1886 and had a family of his own to care for. Another blow had come when Emma Naomi died in 1876 at 21 “from consumption.” Faced with all their difficulties, the poet must have persuaded her mother that Toronto, the publishing centre of English Canada, was the place where she could best earn a living. When they left Peterborough is not known.

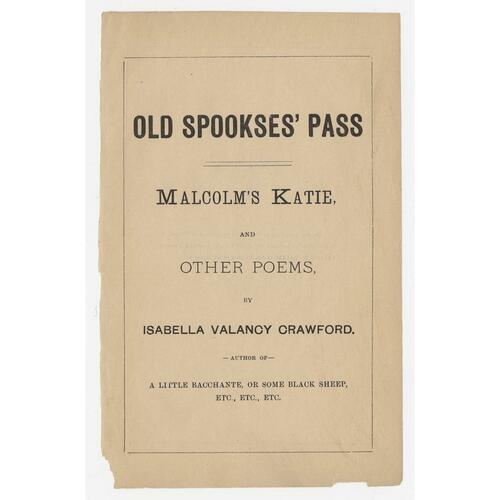

The story of Isabella Valancy Crawford’s literary struggles has been vividly sketched by Katherine Hale in the introduction to her anthology. Crawford published one book of poetry, Old Spookses’ Pass, Malcolm’s Katie and other poems, at her own expense in 1884. For this she received scant reward in her lifetime (only 50 copies were sold), although there were notices in such London journals as the Spectator, the Graphic, the Leisure Hour, and the Saturday Review. These articles pointed to “versatility of talent,” and to such qualities as “humour, vivacity, and range of power,” which were impressive and promising despite her extravagance of incident and “untrained magniloquence.” In the 20th century critics have given the work increasing respect and appreciation.

In Toronto from 1883 until her death in 1887 the poet lived with her mother in boarding-houses on Adelaide Street, then in rooms at 180 Adelaide Street West, and then at 57 John Street, sending out a quantity of “occasional” verse to the Toronto papers, a number of serialized novels and novellas for Frank Leslie’s New York publications, and articles for the Fireside Monthly. In 1886 she became the first local writer to have a novel, A little Bacchante, serialized in the Evening Globe. For the most part Crawford’s prose followed the fashion of the feuilleton of the day. It was romantic-Gothic “formula fiction.” Yet there are indications that the young woman possessed other gifts, such as the ability to write contes concerning pioneer life in Canada West. Her fairy stories written in Lakefield reveal a youthful delight in music, poetry, and nature.

A woman of brilliant intellect, well acquainted with world culture, Isabella had grown up not in her parents’ Dublin but in a pioneer society. It must have become clear to her early that there would be few sympathizers with her imaginative gifts, and she would have to leave them aside to earn a living for herself and her mother. The only avenue open was the popular magazines and newspapers, and for them she wrote light “homely” verse, humorous sketches, short romantic stories, and melodramatic novelettes. Her creative life was far from that of Emily Dickinson who perfected her poetry in seclusion.

Yet Isabella’s poetry has survived. Although no comprehensive critical analysis of her work has yet been published, the poetry is now receiving serious study. She was, in one sense, a Victorian poet, for whom Tennyson was the guide and idol. But in her long poems, “Malcolm’s Katie,” an idyll recreating the backwoods life of farm and forest, and “Old Spookses’ Pass,” relating a stampede during a cattle drive through the Rockies, she displays a remarkable flair for narrative, and for combining plot, theme, and characterization with an exuberant and arresting use of imagery. In the former poem she presents a new myth of great significance to Canadian literature: the Canadian frontier as creating “the conditions for a new Eden,” not a golden age or a millennium, but “a harmonious community, here and now.” Crawford’s social consciousness and concern for humanity’s future committed her, far ahead of her time and milieu, to write passionate pleas for brotherhood, pacifism, and the preservation of a green world. Her deeply felt belief in a just society wherein men and women would have equal status in a world free from war, class hatred, and racial prejudice dominates all her finest poetry regardless of whether she was using Graeco-Roman, Vedantist, Scandinavian, or North American Indian sources. These are sources that Longfellow too used but one has only to consider the imaginative intensity and the originality of language in her Indian “South Wind” sequences or in “Gisli, the Chieftain” to recognize how great was her talent and how well her poetry stands up to comparison with the work of her contemporaries.

[Although only one book, Old Spookses’ Pass, Malcolm’s Katie, and other poems ([Toronto], 1884), was published during her lifetime, Isabella Valancy Crawford’s contributions to newspapers and journals consisted not only of numerous poems but also of many prose works including: “A five-o’clock tea” which appeared in volume 17 (January–June 1884): 287–91, of Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly (New York); “Extradited” which was published in the Globe, 4 Sept. 1886, and was republished in volume 2 (1973), no.3: 168–73, of the Journal of Canadian Fiction (Montreal); and “A little Bacchante” which was serialized in the Evening Globe in 1886. J. W. Garvin edited the first posthumous collection of her poetry, The collected poems of Isabella Valancy Crawford (Toronto, 1905); 18 years later his wife, Katherine Hale, published Isabella Valancy Crawford (Toronto), an anthology of poetry which also included biographical information. The 1970s saw a rebirth of interest in the work of Crawford, and Garvin’s collection was reprinted in 1972 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y.) with an introduction by James Reaney. Three years later Selected stories of Isabella Valancy Crawford, edited by Penny Petrone and published in Ottawa, appeared and, in 1977, a previously undiscovered poem, named Hugh and Ion, was published by Glenn Clever More complete descriptions of Crawford’s works can be found in “Annotated bibliography of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” comp. Lynne Suo, Essays on Canadian Writing (Downsview, Ont.), 11 (summer 1978): 289–314, and “A preliminary checklist of the writings of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” comp. Margo Dunn, The Crawford symposium, ed. F. M. Tierney (Ottawa, 1979), 141–55.

Most of Crawford’s unpublished writing is held by the Queen’s University Archives and is described in Acatalogue of Canadian manuscripts collected by Lorne Pierce and presented to Queen’s University, [comp. Dorothy Harlowe, ed. E. C. Kyte] (Toronto, 1946), 100–4. d.l.]

Evening News (Toronto), 13 June 1884. Evening Telegram (Toronto), 12 June 1884, 14 Feb. 1887. Globe, 14 June 1884, 14 Feb. 1887. Graphic: an Illustrated Weekly Newspaper (London), 4 April 1885. Illustrated London News, 3 April 1886. Leisure Hour (London), 34 (1885): 165. Mail (Toronto), 24 Dec. 1873. Saturday Rev. of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art (London), 23 May 1885. Spectator (London), 18 Oct. 1884. Varsity (Toronto), 23 Jan. 1886. Week (Toronto), 11 Sept. 1884, 24 Feb. 1887. The Crawford symposium, ed. F. M. Tierney (Ottawa, 1979). Roy Daniells, “Crawford, Carman, and D. C. Scott,” Literary history of Canada: Canadian literature in English, ed. C. F. Klinck et al. (Toronto, 1965), 406–10. Margo Dunn, “The development of narrative in the writing of Isabella Valancy Crawford” (ma thesis, Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby, B.C., 1975). Pelham Edgar, “English-Canadian literature,” The Cambridge history of English literature, ed. A. W. Ward and A. R. Waller (15v., Cambridge, Eng., 1907–27), XIV: 343–60. S. R. MacGillivray, “Theme and imagery in the poetry of Isabella Valancy Crawford” (ma thesis, Univ. of New Brunswick, Fredericton, 1963). C. F. MacRae, “The Victorian age in Canadian poetry” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1953). Patricia O’Brien, “Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Peterborough, land of shining waters: an anthology (Peterborough, Ont., 1967), 379–83. James Reaney, “Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Our living tradition, second and third series, ed. R. L. McDougall (Toronto, 1959), 268–88. Frank Bessai, “The ambivalence of love in the poetry of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Queen’s Quarterly, 77 (1970): 404–18. L. J. Burpee, “Isabella Valancy Crawford: a Canadian poet,” Poet Lore: A Magazine of Letters ([Boston]), 13 (1901): 575–86. H. W. Charlesworth, “The Canadian girl: an appreciative medley,” Canadian Magazine, 1 (March–October 1893): 186–93. J. M. Elson, “Pen sketches of Canadian poets: Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Onward: a Paper for Young Canadians (Toronto), 5 March 1932. Dorothy Farmiloe, “I. V. Crawford: the growing legend,” Canadian Literature (Vancouver), 81 (summer 1979): 143–47. Northrop Frye, “Canada and its poetry,” Canadian Forum (Toronto), 23 (1943–44): 207. Robert Fulford, “Isabella Crawford: grandmother figure of Canadian literature,” Toronto Star, 10 Feb. 1973: 77. J. W. Garvin, “Who’s who in Canadian literature: Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Canadian Bookman (Toronto), 9 (1927): 131–33. E. J. Hathaway, “How Canadian novelists are using Canadian opportunities,” Canadian Bookman (Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Que.), 1 (1919), [no.31]: 18–22; “Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Canadian Magazine, 5 (May–October 1895): 569–72. K. J. Hughes, “Democratic vision of ‘Malcolm’s Katie,’” CVII: Contemporary Verse Two (Winnipeg), 1 (1975), no.2: 38–46. K. J. Hughes and Birk Sproxton, “‘Malcolm’s Katie’: images and songs,” Canadian Literature, 65 (summer 1975): 55–64. Donald Jones, “Canadian poetess’ home discovered on King Street,” Toronto Star, 29 Nov. 1980: H8. Dorothy Livesay, “The hunters twain,” Canadian Literature, 55 (winter 1973): 75–98; “Tennyson’s daughter or wilderness child? The factual and the literary background of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Journal of Canadian Fiction, 2: 161–67. M. F. Martin, “The short life of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Dalhouise Rev., 52 (1972–73): 390–400. J. B. Ower, “Isabella Valancy Crawford: ‘The canoe,’” Canadian Literature, 34 (autumn 1967): 54–62. E. M. Pomeroy, “Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Paisley Advocate (Paisley, Ont.), 12 Feb. 1930; “Isabella Valancy Crawford (December 24th, 1850–February 12th, 1887),” Canadian Poetry Magazine (Toronto), 7 (1943–44), no.4: 36–38. “A rare genius recalled,” Globe, 13 March 1926. C. S. Ross, “I. V. Crawford’s prose fiction,” Canadian Literature, 81: 47–59. M. M. Wilson, “Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Globe, Saturday magazine sect., 15, 22 April 1905. Ann Yeoman, “Towards a native mythology: the poetry of Isabella Valancy Crawford,” Canadian Literature, 52 (spring 1972): 39–47.

Cite This Article

Dorothy Livesay, “CRAWFORD, ISABELLA VALANCY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/crawford_isabella_valancy_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/crawford_isabella_valancy_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Dorothy Livesay |

| Title of Article: | CRAWFORD, ISABELLA VALANCY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |