As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

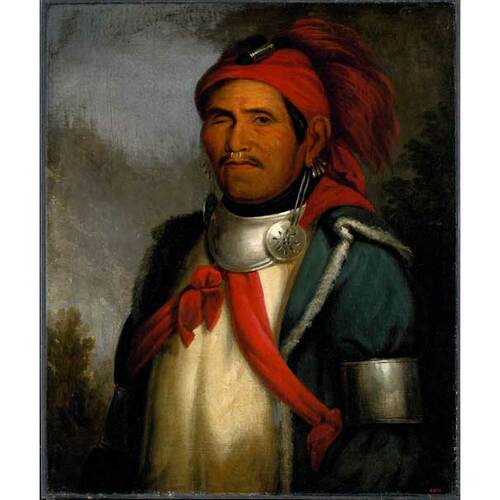

TENSKWATAWA (Elskwatawa, first named Lalawethika, also known as the Shawnee Prophet and the Prophet), Shawnee religious and political leader; b. probably in early 1775 in Old Piqua (near Springfield, Ohio), son of Puckeshinwa, a Shawnee warrior, and Methoataske, a woman of Creek descent; m. and had several children; d. November 1836 in what is now Kansas City, Kans.

Tenskwatawa’s father was killed prior to his birth and the boy was abandoned by his mother, probably in 1779. As a child he was given the name of Lalawethika, meaning “rattle” or “noisemaker,” which was indicative of his loud or boisterous personality, and he was raised by Tecumpease, an elder sister. His boyhood was overshadowed by two elder brothers, Chiksika and Tecumseh*, who were successful and admired by their peers. In contrast Lalawethika seems to have been an outcast, tolerated by his family but disliked by many members of the tribe. During his childhood he lost the sight of his right eye in an accident, and while an adolescent he became an alcoholic. As a young man he married, but failed to excel as a hunter or warrior. Although he did not participate in the Indian victories over Josiah Harmar and Arthur St Clair [see Michikinakoua*], he was present at the battle of Fallen Timbers and probably attended the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

Following the treaty Lalawethika lived in western Ohio with a small band of Shawnees led by Tecumseh. In 1797 the band moved to eastern Indiana, where Lalawethika fell under the tutelage of Penagashea (Changing Feathers), an ageing medicine man. In 1804, upon the latter’s death, he aspired to the status of shaman. Meanwhile, the Shawnees and other tribes were hard pressed to defend their traditional way of life against the advancing frontier. As the number of game animals dwindled and the fur trade declined, the Indians’ economic base disintegrated. Many tribes were forced to make land cessions. Others suffered from alcoholism and disease, while traditional values among all the tribes seemed to be dissolving.

Although Lalawethika at first failed as a shaman, in the spring of 1805 he experienced a series of visions which changed his life. He claimed that during a trance he died and was carried to heaven where the Master of Life showed him both a paradise and a hell where unrepentant alcoholics like himself were subjected to fiery tortures. He renounced alcohol and declared that the Master of Life had chosen him to deliver the Indians from all their problems. He also declared that he would take a new name: Tenskwatawa, “the open door.”

Tenskwatawa preached a doctrine which attempted to revitalize certain parts of traditional Indian culture and to modify others. He asked his followers to return to the communal life of their fathers. He also urged them to maintain good relationships with members of their families and their tribe. Above all, they should renounce alcohol and many other products of American culture. He informed his disciples that although the Master of Life had made the Indians, the British, the French, and the Spaniards, the Americans were the children of the Great Serpent, the evil power in the universe. The Indians were to avoid them. Indian women married to American men were to return to their tribes and the children of such unions were to remain with their fathers. Christian Indians were ordered to abandon their faith.

Instead, Tenskwatawa required his followers to pray to the Master of Life and provided them with “prayer sticks” inscribed with instructions for such petitions. He restored some traditional Shawnee dances and ceremonies, but forbad others and offered new rituals in their place. He ordered his followers to discard their personal medicine bags since these talismans no longer possessed any potency. If his disciples followed his instructions, game would return to the forests, and their dead friends and relatives would be brought to life. The Americans would be swept away (Tenskwatawa never provided an explicit description of this phenomenon) and the land would be restored to the Indians.

Tenskwatawa’s teachings found a receptive audience among the tribes of Ohio and Indiana. During the summer of 1805 he established a new village near Greenville, in western Ohio. In the following months many Delawares in eastern Indiana were converted, and in March 1806 at Woapikamunk, a village on the White River, Tenskwatawa assisted the Delawares in assessing the guilt of some tribesmen accused of witchcraft. The Delawares eventually burned four of their kinsmen at the stake before the witch-hunt ceased. In May, Tenskwatawa conducted a similar purge among the Wyandots on the Sandusky River, but pro-American chiefs interceded to save the accused.

Alarmed by Tenskwatawa’s growing ascendancy, William Henry Harrison, governor of Indiana Territory, attempted to discredit the Shawnee and wrote to the Delawares instructing them to ask Tenskwatawa to perform a miracle: “Ask of him to cause the sun to stand still – the moon to alter its course.” On 16 June 1806 Tenskwatawa successfully predicted a near-total eclipse of the sun and his influence was markedly increased. During 1807 and 1808 Indians from many tribes travelled hundreds of miles to meet with him at Greenville. Kickapoos, Sauks and Foxes, Potawatomis, Ottawas, Menominees, and Winnebagos all journeyed to his village, and in the summer of 1808 so many Ojibwas were en route to Greenville that white traders found most of their villages on the southern shore of Lake Superior deserted. The influx alarmed American officials who sent several parties of agents to investigate the Prophet’s movement, but he was able to convince them that his followers wished only to live in peace. The large numbers of Indians depleted his food supplies and American settlers in Ohio remained hostile to his movement. Hoping to relocate at a greater distance from the American frontier, where game was more plentiful, Tenskwatawa abandoned Greenville and in the spring of 1808 he established a new settlement, Prophetstown (Battle Ground, Ind.), at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River.

After this move Tenskwatawa developed ties with the British Indian Department. In June 1808 he sent Tecumseh to Amherstburg, Upper Canada, where he met with the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, William Claus*, and the lieutenant governor, Francis Gore*, asking for arms and provisions. To ease American suspicions, in August 1808 Tenskwatawa journeyed to Vincennes (Ind.), where he convinced Harrison that he was friendly to the United States and even persuaded him to provide food for his followers. But Tenskwatawa still could not feed all the Indians arriving at Prophetstown, and during the winter of 1808–9 many died. In the spring relations between Tenskwatawa’s movement and the United States deteriorated as the Indians became alarmed over American attempts to purchase additional lands.

On 30 Sept. 1809 the Treaty of Fort Wayne, signed by representatives from the Miamis, Delawares, and Potawatomis, transferred over three million acres of Indian lands in Illinois and Indiana to the United States. It was a watershed in Tenskwatawa’s career. Although he had opposed the agreement, he could not stop it, and many of his followers now rejected his religious leadership for the more political and military policies espoused by Tecumseh. Tenskwatawa continued to exert influence among the Indians at Prophetstown, but Tecumseh slowly eclipsed him. While Tenskwatawa remained on the Tippecanoe, Tecumseh travelled widely, using his brother’s religious movement as the base for the political and military unification of all the tribes.

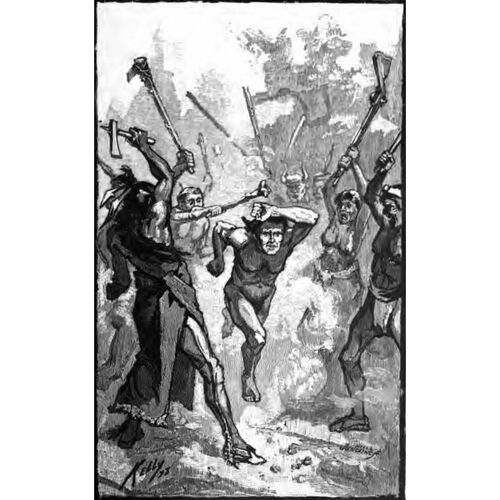

During the winter of 1810–11 the Prophet received several shipments of British provisions, and in the spring he met with a series of American emissaries sent by Harrison. Tenskwatawa treated them cordially, but in June 1811 he seized a shipment of American salt on the Wabash River. Later in the summer, when Tecumseh left Prophetstown to enlist the southern tribes, Tenskwatawa again remained behind, agreeing to protect the village but avoid a confrontation with Harrison. The governor then led an army of approximately 1,000 men against Prophetstown. They arrived at the Tippecanoe on 6 November and arranged to meet with Tenskwatawa on the following morning. Rather than surrender his village and supplies, Tenskwatawa decided to attack and he spent the night assuring his followers that his medicine would protect them from American bullets. Just before dawn on 7 November, about 700 Indians attacked the American camp while Tenskwatawa remained in the village praying for victory. After a three-hour battle the Indians withdrew and Tenskwatawa abandoned Prophetstown. Harrison claimed a victory, but both sides suffered similar casualties (60 to 70 killed).

The battle of Tippecanoe ended Tenskwatawa’s claims of religious leadership, but he remained with Tecumseh, assisting in his brother’s attempts to unify the tribes politically. A new village was built near the site of Prophetstown. Although the Shawnee brothers endeavoured to persuade the Americans that they would remain at peace, they strengthened their ties with the British. In June 1812 Tecumseh journeyed to Amherstburg while Tenskwatawa met with Indians who once again were arriving at their village. When news of the War of 1812 reached Indiana, Tenskwatawa went to Fort Wayne professing friendship to the United States, but after the fall of Detroit in August he urged the Indians in his village to attack Fort Harrison (Terre Haute, Ind.). The attack failed, and in December, after American military expeditions swept through the Wabash valley, Tenskwatawa fled to Upper Canada.

He did not remain there long. In the spring of 1813 he accompanied Tecumseh back to Indiana where they recruited warriors to assist the British in the defence of the Detroit region. They returned to Amherstburg on 16 April, and in May Tenskwatawa joined a large force of British and Canadian troops which besieged Fort Meigs (near Perrysburg, Ohio). Tenskwatawa took no part in the fighting, and following the siege he returned to Michigan where he spent the summer of 1813 at a small village on the Huron (Clinton) River. He did not participate in the British campaigns into Ohio in July and August, but he did meet with pro-American Wyandots at Brownstown (near Trenton, Mich.) where he opposed their efforts to detach the Indians from the British. In September he accompanied Major-General Henry Procter*’s forces as they abandoned Amherstburg and retreated east. On 5 Oct. 1813 Tenskwatawa was present at the battle of Moraviantown, but again took no part in the fighting and he accompanied Procter’s party when it fled before the advancing Americans.

Following the battle Tenskwatawa spent the winter at the western end of Lake Ontario, attempting to reassert his leadership. He was supported by John Norton* of the Grand River Iroquois, and in the spring he and a small band of followers moved to the Grand River where Norton supplied them with food and other provisions. Although he was reluctant to assist the British in the further defence of Canada, in the summer he finally consented to lead a war party to the Niagara frontier. Yet he arrived on 6 July 1814, after the battle of Chippawa had ended, and his precipitate withdrawal on the following day resulted in a general Indian retreat that threatened the British position. He refused to participate in any further military actions, but he attended the conference at Burlington Heights (Hamilton) in April 1815 at which Indian agents announced that the war had ended.

In June 1815 Tenskwatawa and most of the other western tribesmen moved to the Amherstburg region in preparation for a return to the United States. He attended the conference at Spring Wells, near Detroit, in September at which the American representatives met with the exiles to negotiate the conditions for their return. At first he cooperated, but when he learned the Americans opposed his return to the Wabash valley, he became angry and went back to Amherstburg. In April 1816 he crossed over to Detroit where he met with Governor Lewis Cass, but was again denied permission to go back to the Tippecanoe. Meanwhile, most of the American Indians left for their former homes, and to encourage such an exodus, the British Indian Department reduced the rations of those exiles remaining in Upper Canada. By 1817 Tenskwatawa’s followers numbered only about two dozen Shawnees, mainly relatives who relied upon him for their sustenance. Embittered, Tenskwatawa established a camp on Cedar Creek, in Essex County, where he lived for the next eight years, relying upon British rations but quarrelling with William Claus, John Askin Jr, and other Indian agents.

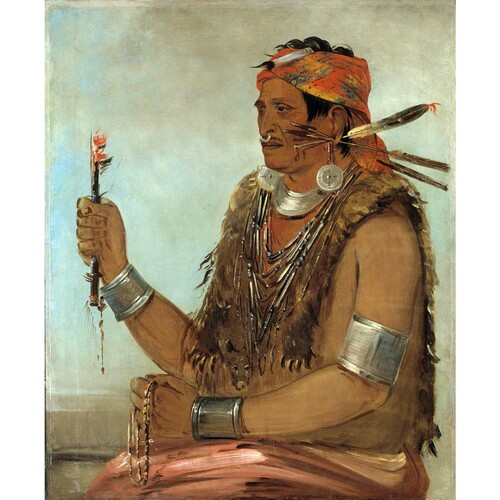

By 1824 the United States no longer considered the Prophet a threat and in July Cass invited him to return to Ohio and use his influence to persuade the Shawnees to remove west of the Mississippi. During the following summer Tenskwatawa led his handful of followers back to Wapakoneta, a Shawnee village in western Ohio, and in October 1826 he accompanied about 250 Shawnees who left Ohio for the west., After spending the winter of 1826–27 near Kaskaskia, Ill., in August 1827 they crossed the Mississippi and travelled as far as western Missouri. In the spring of 1828 they arrived at the Shawnee reservation in eastern Kansas. Tenskwatawa spent the remaining nine years of his life in relative obscurity, although he did pose for the artist George Catlin in 1832. He died in what is now Kansas City in November 1836.

During the War of 1812 and in the following decades most whites assumed that Tecumseh had dominated the Indian movement which emerged during the first decade of the century. His emphasis upon a centralized political leadership, although foreign to the tribesmen, seemed logical to them because it reflected their own political beliefs. Moreover, since Tecumseh seemed to epitomize the “noble savage,” after his death white historians and writers enshrouded his life with apocrypha which made him a legendary figure. In contrast, Tenskwatawa usually has been portrayed as a religious charlatan who briefly ascended to a position of limited importance through his association with his brother. Yet Tenskwatawa initially dominated the Indian movement and his teachings were the magnet which drew the Indians together. During periods of social and economic deprivation Indian people often have turned to religious leaders for deliverance [see Abishabis] and Tenskwatawa’s promises offered such a solution. The Indian coalescence remained a religious movement until 1810, when Tecumseh began to transform the Prophet’s followers into a political and military confederacy. Since whites possessed little understanding of Indian religious beliefs, Tenskwatawa’s teachings seemed strange and ellogical and they dismissed the Prophet as a bizarre religious figure of minor importance. Yet his faith seemed logical to people of his own culture. In the years between 1805 and 1810 Tenskwatawa was one of the most influential Indians in the Great Lakes region and he dominated the tribes’ resistance to American expansion.

For a more complete listing of material relating to Tenskwatawa, the reader is referred to R. D. Edmunds, The Shawnee Prophet (Lincoln, Nebr., and London, 1983).

Tippecanoe County Hist. Assoc., County Museum (Lafayette, Ind.), George Winter papers. Wis., State Hist. Soc., Draper mss, ser.T; 1YY–13YY. Benjamin Drake, Life of Tecumseh and of his brother the Prophet; with a historical sketch of the Shawanoe Indians (Cincinnati, Ohio, 1841; repr. New York, 1969). B. J. Lossing, The pictorial field-book of the War of 1812 . . . (New York, 1869). Messages and letters of William Henry Harrison, ed. Logan Esarey (2v., Indianapolis, Ind., 1922). “Shabonee’s account of Tippecanoe,” ed. J. W. Whickar, Ind. Magazine of Hist. (Bloomington), 17 (1921): 353–63. The battle of Tippecanoe: conflict of cultures, ed. Alameda McCollough (Lafayette, 1973). C. C. Trowbridge, Shawanese traditions: C. C. Trowbridge’s account, ed. [W.] V. Kinietz and Erminie Wheeler-Voegelin (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1939).

Cite This Article

R. David Edmunds, “TENSKWATAWA (Elskwatawa, Lalawethika) (Shawnee Prophet, Prophet),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tenskwatawa_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tenskwatawa_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. David Edmunds |

| Title of Article: | TENSKWATAWA (Elskwatawa, Lalawethika) (Shawnee Prophet, Prophet) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |