Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

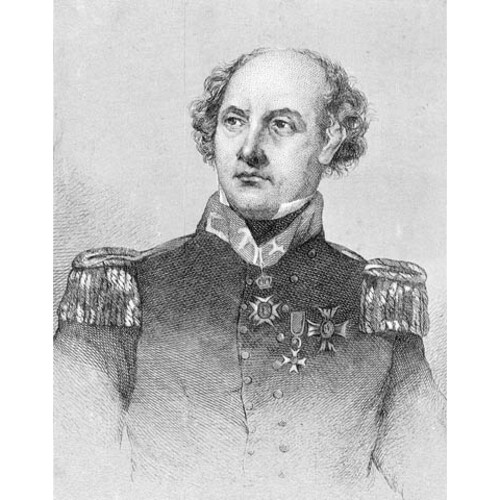

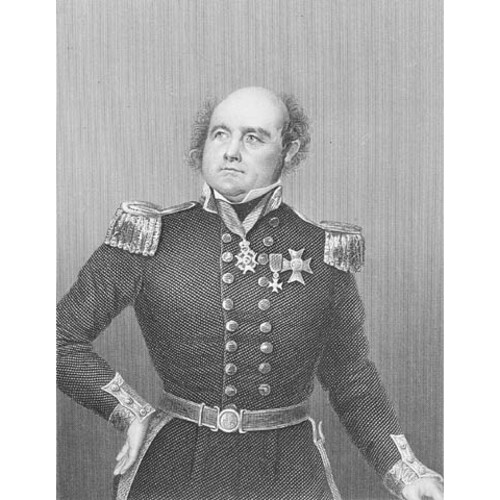

FRANKLIN, Sir JOHN, naval officer, explorer, colonial governor, and author; b. 16 April 1786 in Spilsby, England, son of Willingham Franklin and Hannah Weeks; m. first 19 Aug. 1823 Eleanor Anne Porden (d. 1825) in London, England, and they had one daughter; m. secondly 5 Nov. 1828 Jane Griffin* in Stanmore (London), England; they had no children; d. 11 June 1847, probably on board hms Erebus near King William Island (Nt).

John Franklin, the ninth child and youngest son in a family of twelve, was born over his father’s shop in the market town of Spilsby. The Franklins had formerly been landowning yeoman farmers, but John Franklin’s great-grandfather and grandfather were so improvident that his father, Willingham Franklin, had gone into trade – then socially frowned upon – as the only way to restore the family’s fortunes. Willingham met with enough success as a dry-goods and fine-cloth merchant that he was able to purchase a small country estate near the village of Mavis Enderby, thus providing his children with the basis for a claim to gentility. John and his siblings evidently shared their father’s ambitious nature: all the daughters, except one who died young and one who was an invalid, married well, and all the sons except one had impressive careers.

The exception among the sons was the eldest, Thomas Adams, who died (possibly by suicide) in 1807 at the age of 33 after an initially flourishing but ultimately disastrous business career. According to family tradition, he was brought down by an unscrupulous, conniving associate. The second son, Willingham, became a successful barrister, received a knighthood, and died of cholera in 1824, at the age of 44, while serving as a justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature in Madras (Chennai), India. The third, Major James Franklin of the East India Company’s Skinner’s Horse (1st Bengal Lancers), was elected a fellow of the Royal Society for his survey work in India; he also died at a relatively early age, succumbing to liver disease in 1834.

John Franklin, although the youngest son, thus became the head of the family, and throughout his life he maintained both warm family ties and a sense of responsibility for his many nieces and nephews. Besides watching over the offspring of Willingham and James, he took a particular interest in the children of his sisters Ann Peacock and Sarah Sellwood – who died in 1808 and 1816 respectively – and of his sister Isabella Cracroft, who was widowed in 1824. Two nieces, Mary Franklin and Sophia Cracroft, were informally adopted by Sir John and his second wife.

As a child, Franklin showed signs of a pious nature, and his father intended him to be a clergyman. However, while Franklin was studying at the King Edward VI Grammar School in Louth as a boarder, a trip to the seaside reinforced his growing interest in the navy. His father arranged for him to go on a merchant voyage to Lisbon as a cabin boy, expecting that the experience would quickly put an end to his romantic dreams, but John returned more set on his plan than ever. Franklin later wrote that his choice of career was not inspired by either the “attractive uniform” or the “hopes of getting rid of school.” Rather, he insisted, he had “pictured to myself both the hardships and pleasures of a sailor’s life (even to the extreme) before ever it was told to me.” He entered the navy as a first-class volunteer in October 1800, at the age of 14, and on 2 April 1801 he took part in the battle of Copenhagen, where British naval forces were commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson.

Soon afterwards, a new opportunity presented itself to Franklin through his family’s connection with Lieutenant Matthew Flinders (an aunt was the second wife of Flinders’s father). Franklin was selected as one of the midshipmen on Flinders’s voyage to New Holland (Australia) aboard hms Investigator. The ship sailed in July 1801. Franklin’s letters during the voyage reveal a young man eager to educate himself broadly and to advance in his profession: in October 1802 he wrote that, along with his study of subjects that included naval tactics, navigation, geography, French, and Latin, he was reading William Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, and Tobias George Smollett for enjoyment. Throughout his life Franklin was, as a niece recalled, “a devourer of books of every kind” who could spend hours “oblivious of all around him.” He learned astronomy and surveying from Flinders, and for his diligence was given the nickname of “Mr. Tycho Brahe.” Flinders reported from Port Jackson (Sydney) that “John Franklin approves himself worthy of notice. He is capable of learning every thing that we can shew him, and but for a little carelessness, I would not wish to have a son otherwise than he is.”

After having surveyed the coast of New Holland between 1801 and 1803, Flinders was forced to end his expedition owing to the unseaworthy condition of the Investigator. He and his men had to take passage in another ship, hms Porpoise, for the homeward voyage. However, the Porpoise and a merchant ship that accompanied it were wrecked near Torres Strait, northeast of mainland Australia. Franklin and 93 others spent nearly two months on a desolate coral bank a quarter of a mile in circumference. After their rescue, the party divided. Franklin’s group travelled to Canton (Guangzhou) and then returned to England with the East India Company’s merchant fleet. Along the way they were attacked by French warships. The French vessels were first repelled and then pursued; Franklin participated in the fight and was later praised by the commodore, Sir Nathaniel Dance, for his “zeal and alacrity.”

Following his return to England in August 1804, Franklin joined hms Bellerophon. The next winter, spring, and early summer were spent blockading the French port of Brest; then the Bellerophon sailed for Spain and on 21 October 1805 played a prominent role in the battle of Trafalgar. The Bellerophon was so close to the French ship L’Aigle that their yardarms became entangled. Franklin, as the midshipman in charge of signals, was stationed on the poop deck and thus was exposed, as he wrote, “for near an hour and a half … to the galling fire of musketry that was continuously poured from the tops of the enemy upon the Bellerophon.” Of the 40 men on the deck, only Franklin and six others “escaped either death or wounds.” (However, Franklin did suffer a mild degree of hearing loss from the constant noise of the cannons and guns.) Following the death of Captain John Cooke, the command fell on the Bellerophon’s first lieutenant, William Pryce Cumby. Cumby then organized a boarding party and captured L’Aigle.

This officer, who became a popular hero after the battle, was much admired by young Franklin. Years later, Franklin wrote to Cumby that he had “endeavoured to follow your model as an officer.… This example has caused me to seek by every means, consistent with the due performance of our Relative duties, the friendship of those with whom I have been associated. When this feeling is evinced on the part of the Commander, it seldom fails of producing the best exertions of your companions.” Cumby’s example did indeed become a key element in Franklin’s approach to leadership, but it was modified by another conviction which Franklin had expressed not long before Trafalgar: that a young man such as himself, who had entered the navy “without having myriads of Nabobs to back him, & insure promotion,” must “strain every nerve in order that his exertions may surpass his commander’s most sanguine expectation.” If in so doing he should “fall a victim to fate,” then his relatives could find comfort in the knowledge that he had died for his country. Franklin usually felt great loyalty to and friendship for subordinates who were willing to “strain every nerve,” but he could be sharply critical of those who were not.

In October 1807 Franklin was transferred to hms Bedford, which escorted the Portuguese royal family to Brazil and then remained in South American waters for two years. Franklin served initially as master’s mate, but on 5 December he was appointed acting lieutenant by Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith; his formal promotion to lieutenant was dated 11 Feb. 1808. Returning to England in 1810, the Bedford spent four years on blockade duty. After the Treaty of Paris was signed on 30 May 1814, ending the war with Napoleon I, the ship formed part of a naval squadron that escorted Britain’s allies, the tsar of Russia and the king of Prussia, to London for the victory celebrations. In September the Bedford sailed for New Orleans, where Franklin took part in the final battle of the War of 1812.

On 14 Dec. 1814 Franklin participated in the battle of Lake Borgne. In charge of the Bedford’s boats during an attack on American gunboats under the command of Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones, Franklin was slightly wounded; nevertheless, he was the first to board one of the American boats and accepted the surrender of its captain. Subsequently, he assisted in cutting a canal between Bayou Catalan and the Mississippi River, and the new passageway allowed the British boats on Lake Borgne to mount an attack against American fortifications on the riverbank.

On 8 Jan. 1815 Franklin was one of 600 British soldiers, sailors, and marines who, under the overall command of Colonel William Thornton, captured the American earthworks on the west bank of the Mississippi. The naval contingent, led by Captain Rowland Money, boldly stormed an American battery even though the British force lacked any artillery support. After heavy fire failed to halt the sailors, the American defenders fled. (The capture of the earthworks was the one successful British action on what was otherwise a day of defeat: the main attack on the American lines around New Orleans was a complete failure.) In a letter to Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Forrester Inglis Cochrane, Major-General John Lambert, the chief army commander, praised Franklin and four other junior naval officers “whose exertions and intelligence have so repeatedly been the admiration of the general and superior officers under whose orders they have been acting on shore.” Franklin was mentioned in dispatches, and Cochrane endorsed Lambert’s strong recommendation that he be promoted.

The Bedford returned to England in May 1815. That July, its commission ended; only a few days later, Franklin was assigned to hms Forth as first lieutenant at the special request of the commander, Captain Sir William Bolton. The Forth in turn was paid off in September; the only significant service on which it had been employed was to carry the exiled Duchesse d’Angoulême, daughter of King Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, back to France. Franklin then spent over two years ashore on half pay.

The outlook was bleak: with the coming of peace, the navy faced drastic reductions in the number of its ships and men. Willingham Franklin Sr, still suffering from the after-effects of a financial disaster that overtook him through his involvement in his son Thomas’s complicated affairs, could do nothing to assist John while he was unemployed. Flinders, who would certainly have given Franklin his support for promotion and an appointment, had died in 1814, and Franklin’s outstanding service at New Orleans seemed to count for little, perhaps because – as Franklin himself bitterly speculated – the British had suffered such an embarrassing overall defeat there. Powerful connections would have helped: Edward Curzon, one of the other lieutenants praised by Major-General Lambert, was promoted in 1815 and given a command in 1816. But as a member of an aristocratic family, Curzon had access to influential patronage networks.

For the middle-class Franklin, another voyage of exploration offered the likeliest path to success, and he therefore refreshed his surveying skills. It was not the ideal solution: as Franklin uneasily noted in a letter to the Investigator’s naturalist, Robert Brown, an absence of several years would mean losing the opportunity to advance his interests with naval officials, and when he returned, perhaps “with a constitution much shattered,” he might find the backers of the voyage either out of office or otherwise unable to secure him the promotion he so “anxiously sought.” Nevertheless, when he heard about a planned naval expedition up the Congo River early in 1816, Franklin applied, having concluded that there was “no other Branch of the Naval Service except the present expedition, which is active or calls for great exertion or is likely to lead to the most desirable result, the obtaining [of] Promotion.”

This application was unsuccessful, but in late 1817 came word that the Admiralty proposed to renew naval exploration of the Arctic. Franklin called on every connection he had: by this time, he had gained the backing of Flinders’s powerful patron, Sir Joseph Banks* (reportedly by carefully surveying part of London and presenting Banks with the result), and his brother Willingham had developed useful contacts at the Admiralty. As a result, on 14 Jan. 1818 Franklin was placed in charge of hms Trent on a new Arctic expedition led by Commander David Buchan.

Along with Buchan’s ship, hms Dorothea, the Trent was ordered to proceed north between Greenland and Spitsbergen (Svalbard, Norway) in the hope that it would be possible to sail over the North Pole and onward to Bering Strait. This plan, which in retrospect appears almost ridiculously impractical, was inspired by decades of reports from whalers that open water had been found north of Spitsbergen, allowing them to reach latitudes as high as 88º or even 89ºN. John Barrow, the second secretary of the Admiralty – a man of scientific as well as naval interests, and an associate of Banks at the Royal Society – had concluded that deep ocean waters could not permanently freeze, even in high latitudes, and he therefore believed that in a favourable season a way over the pole could be found. The moment seemed especially propitious for such a venture because the northern ice was reportedly breaking up to an unprecedented degree. At the same time, another expedition under Commander John Ross* would sail to Baffin Bay in quest of the northwest passage.

Franklin quickly formed a friendship with Ross’s second in command, William Edward Parry*. After long discussions on scientific and other matters, Parry recorded his impression that Franklin was “the most clever man of our cloth … with whom I have conversed for some time.” Like Parry, Franklin was delighted by the attention that the officers of the expedition received from both scientific men and members of fashionable society. As he reported to his family, “in all places and every Society the expedition is the grand topic of conversation and the very circumstance of belonging to it seems to be a sufficient introduction any where.” When he read an admiring poem on the expeditions by the young writer Eleanor Porden, Franklin asked for an introduction to her; five years later, she would become his wife.

Buchan’s ships sailed from Deptford (London) on 25 April 1818. Though they were equipped to winter in the Arctic, they returned in October; the ice had proved to be heavy, and the Dorothea had sustained extensive damage during a gale. Buchan’s orders were that, if one ship was disabled, he was to continue in the other; this he was loath to do, for fear that he might seem to have deserted the men in the crippled Dorothea. Franklin, determined to make the most of his opportunity, asked for permission to take the Trent on alone, so fulfilling the order not to turn back. Buchan, however, ignored the Admiralty’s instructions “rather than subject his crew to the risk of proceeding home singly in a vessel so shattered and unsafe.” He was not censured for this decision, but he was never employed on Arctic service again, nor was he promoted for his Arctic work.

Once back in England, Franklin renewed his acquaintance with Eleanor Porden. Yet his thoughts were not focused entirely on romance: Porden was an heiress, and if Franklin hoped to marry her he would have to distinguish himself. He put forward a plan for an expedition over the ice floes towards the North Pole, using boats mounted on sledge-runners. At the time, the Admiralty rejected the proposal, but at the urging of Sir Humphry Davy, it later became the basis for Parry’s 1827 expedition. (The plan would fail because the southward drift of the ice made sufficient progress impossible.) Despite the negative response, the boldness of the project and Franklin’s determination to continue as an Arctic explorer had impressed Barrow. Early in 1819 Franklin was appointed to command a new expedition.

The 1819 expedition was an overland one, intended to operate in conjunction with a voyage by Parry to Lancaster Sound. Officially, it was sent out by the colonial secretary, Lord Bathurst, but the orders were drafted by Barrow. Together, the two ventures formed Barrow’s response to the failure of the expedition undertaken by Ross the previous year. Like Buchan, Ross had turned back without reaching his objective, but to Barrow’s mind there was far less justification in his case. Barrow believed that Lancaster Sound was the most likely entrance to the northwest passage; Ross, however, was certain he saw mountains blocking the way to the west. Without further investigation, he retreated. Once Barrow learned that several junior officers were not convinced of the land’s existence, he decided to send out a new expedition to Lancaster Sound under Parry’s leadership.

Franklin, meanwhile, was to travel through Rupert’s Land northwest to the Arctic coast, likely by way of the Coppermine River, then turn eastward and continue “from thence along the Northern Shore of America to [Roes] Welcome, or Baffin’s Bay or wherever that shore may terminate.” In other words, his party was to cover most of the northwest passage in canoes or on foot, while Parry attempted to sail through the entire passage, travelling in the opposite direction in the considerably greater comfort of his ships. Strangely, while the instructions given to Buchan, Ross, and Parry carefully outlined the circumstances under which they were to abandon their missions, no such clauses were included in Franklin’s orders.

Previously, the only white man to have reached the mouth of the Coppermine was Samuel Hearne*, who arrived there in 1771 and would give its latitude as 71°55'N. The accuracy of Hearne’s narrative was often doubted, however, mainly because of persistent rumours that his original journal had been much altered by a ghostwriter before it was published in 1795. If the Coppermine met the sea at a lower latitude than Hearne had reported, the outlook for Parry’s success would be more promising. (In fact, Hearne had placed the river’s mouth too far north by about 200 miles.) It was hoped that the two expeditions might meet; if not, Franklin, during his eastward march along the Arctic coast, was to set up caches and leave information about the area he had covered for Parry’s use. Franklin was given a copy of Hearne’s original journal, and he observed that the entries were “somewhat similar to the printed book.” He therefore was “not prepared to go the length of some persons and doubt his statements altogether,” but he thought that Hearne had “left a tolerably wide field for observation” and hoped “to search beyond him.” Since 1815 Franklin had sought a peacetime outlet for his ambitions, and the overland expedition was the most promising opportunity that had thus far been offered. New geographical discoveries, as he was well aware, would make his name.

Franklin’s expedition was hastily planned and carried relatively few supplies of its own. However, the Admiralty and the Colonial Office had been assured by the representatives of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in London that ample assistance would be forthcoming. In particular, the HBC undertook to provide “Halfbreed Guides, Interpreters of the Chippewayan Language, Hunters and Attendants for the purpose of conveying provisions and Baggage.” At the last minute, application was also made to Simon McGillivray of the rival North West Company (NWC) and Franklin was given a letter of introduction to the company’s agents. At the same time, explorer Sir Alexander Mackenzie* provided detailed suggestions as to how Franklin should proceed. Franklin was instructed to gather what information he could from local sources before he decided on his final plan.

The prospect must have seemed reasonably encouraging, despite the magnitude of the task. Two days before his departure, Franklin was walking in London with Porden and nearly proposed to her, but did not because he “considered it unfair to bind the affections of any Lady at the commencement of a voyage which promised so much danger as ours did.” Porden later claimed that if she had been asked she would not have accepted him, feeling herself bound instead to look after her ageing parents, but she admitted that “I believe you carried a large share of my heart with you, for you were certainly more in my head than I could very well account for.”

Franklin’s companions were two midshipmen, George Back* and Robert Hood*, naval surgeon John Richardson*, and sailor John Hepburn*. The Colonial Office arranged passages for the members of the expedition in an HBC ship. They left England on 23 May 1819 and arrived at York Factory (Man.) on 30 August. To their surprise, the explorers found that Angus Shaw*, John George McTavish, and other partners of the NWC were being detained there as prisoners. Until then, Franklin had been ignorant of how bitter and even violent the conflict between the two trading companies had become. Now he learned that “both companies were arming to the extent of their means for a decisive contest next summer.” He quickly directed his followers to do nothing that might be construed as interference. Yet some of the NWC men had wintered farther north than their rivals, and Franklin turned to them as well as to the HBC employees for advice.

There was a clear consensus that his best course would be to follow the fur-trading routes via rivers and portages as far north as he possibly could (that is, to the Athabasca and Great Slave Lake districts); from there, he could strike out for the Coppermine. However, the HBC supplied only one boat, which was not enough to carry even the limited supplies Franklin had brought. Most of the provisions, as well as the goods brought for barter with aboriginal people, were left behind either at York Factory or along the route to Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River; the companies promised to forward them later. Franklin was eager to press ahead and make arrangements for the northern journey. He, Back, and Hepburn left Cumberland House on a nearly 800-mile snowshoe trip to Lake Athabasca in mid January 1820. Richardson and Hood were to follow in the spring with supplies, which both companies pledged to contribute.

In the Athabasca district, the NWC was far more strongly established than the HBC. The explorers therefore stayed at the NWC’s Fort Chipewyan (Alta) rather than at the HBC post. Through correspondence with Willard Ferdinand Wentzel at Fort Providence (Old Fort Providence, N.W.T.), the NWC post on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake, Franklin arranged for an indigenous band known as Copper Indians – a subgroup of the Dene sometimes called the Yellowknives – to join the expedition as hunters. He also recruited a crew of NWC voyageurs. Unfortunately, Richardson and Hood brought far fewer provisions than had been expected. When the party left Fort Chipewyan on 18 July 1820, they had only enough food for about a week and had to live mainly by fishing along the way. They met the Yellowknife leader, Akaitcho, and his band near Fort Providence and then continued their journey northward on 2 Aug. 1820. A winter station, named Fort Enterprise, was established within easy reach of the Coppermine.

During the winter, Back was sent to the Lake Athabasca posts to secure more provisions. At one of them he encountered the energetic, dictatorial George Simpson*, who had been ordered to strengthen the HBC’s position in the district. Simpson was determined to give only a minimum of assistance to the expedition, reasoning that “their necessities are a very secondary consideration to our own difficulties.” Moreover, Simpson resented the explorers’ good relations with the NWC. To a list of complaints on this score in his journal he added a number of uncomplimentary remarks about Franklin, whom he had never met. Although the senior officers of the NWC remained friendly, their representative at Fort Providence, Nicholas Weeks, compounded Franklin’s difficulties by inexplicably fuelling rumours that the explorers were merely impoverished “wretches” whose aim was to obtain food they could not pay for. When the caribou returned in the spring, Akaitcho refused to hunt until Franklin, after much effort, had convinced him that he would indeed be paid for his services in trade goods once the expedition’s supplies were brought from York Factory.

Franklin thus began his northern journey in July 1821 with inadequate provisions. He planned to survive by hunting and by obtaining food from the Inuit. But, even though over 12,000 pounds of fresh meat were consumed along the way, the requirements of men performing such heavy labour were high, and, without the stores promised by the two companies, the explorers had little to fall back on when game was scarce. Franklin might, of course, have given up altogether at this point and returned to England, but his orders did not specify the conditions under which he could consider such a course justified. Moreover, Franklin had shown great resourcefulness in advancing as far as he had done, and the ambition with which their naval training had imbued him and the other officers would scarcely have permitted them to throw away their hard-earned opportunity. If they had turned back, as Ross and Buchan had done three years earlier, they might have destroyed their careers.

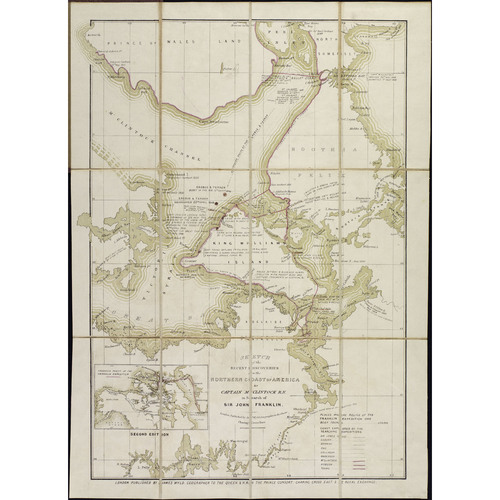

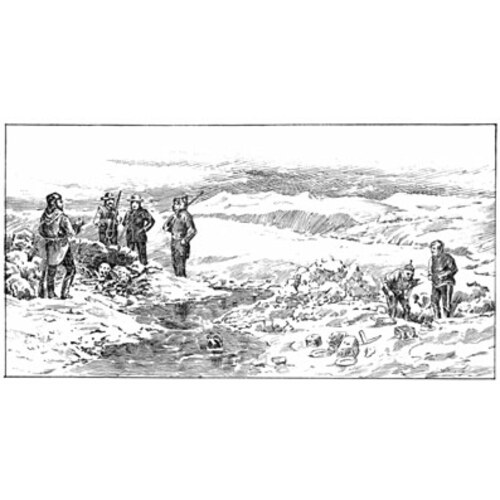

The expedition descended the Coppermine to the sea and proved that the position given in Hearne’s published journal was wrong. The eastward journey along the coast was impressive in terms of miles covered (over 600), but much less so in terms of longitude: tracing the deep indentations of Arctic Sound, Bathurst Inlet, and Melville Sound meant that they covered less than half the distance to Roes Welcome Sound, although if they had been able to travel in a straight line they would nearly have reached it.

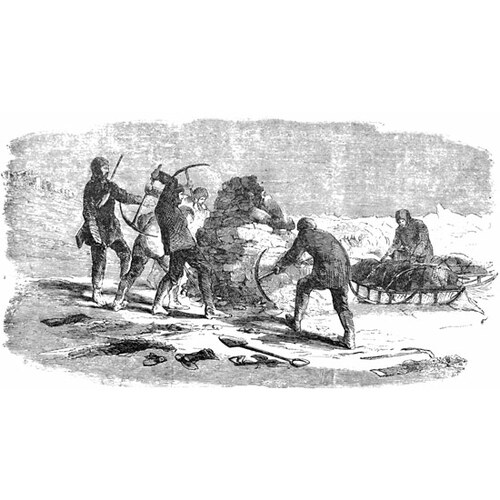

There was no contact with the Inuit after the explorers left the Coppermine, but hunting initially provided enough for survival. Franklin pushed forward until 21 August; by then it was too late to return by the same route, so he began a shorter overland trek directly to Fort Enterprise. However, the caribou had started their southward migration much earlier than in the previous year, and living off the land became barely possible. The voyageurs, unused to the naval command structure and more knowledgeable about the country, frequently clashed with the officers. The weakest members of the expedition were left behind while Franklin and others went on to find help; among the first group, murder and cannibalism took a high toll, and starvation killed some in the second. In total, 11 of the 20 men, including Hood, died before the survivors were rescued by Akaitcho’s hunters. The explorers spent the winter at Fort Resolution and then made their way back to England, where they arrived in October 1822.

For Franklin the disaster had a far-reaching and deeply personal aspect. During the winter at Fort Enterprise, his early piety had been intensified by his reading of religious books donated to the expedition by an evangelical aristocrat, Lady Juliana Lucy Barry. Some of the books were taken on the northern journey for daily reading, and these provided essential emotional sustenance not only to Franklin but also to Richardson and the sole Englishman to die on the expedition, Hood. Franklin later wrote to his brother Willingham that he had “never experienced Such … happiness from the comforts of religion as in the moments of the greatest distress, when there scarcely appeared any reason to hope that my existence could be prolonged beyond a few days.” This religious feeling was quietly yet strongly asserted in Franklin’s Narrative of a journey to the shores of the polar sea, in the years 1819, 20, 21, and 22, which was published to great acclaim in April 1823. Franklin bluntly summed up his travels as “long, fatiguing, and disastrous,” but, despite the expedition’s failure to achieve its goal and the number of deaths that had occurred, the public considered him a hero for the stoical Christian fortitude with which he had endured his sufferings.

In the expedition’s absence Franklin had been promoted commander, and on 20 Nov. 1822 he received his long-coveted captain’s commission. He and Eleanor Porden quickly became engaged; with his captain’s pay, his future wife’s inherited income, and the money he earned from his book, Franklin’s future was secure. The social and literary circles in which Porden moved were ready to welcome him as the lion of the season. Yet Franklin initially resisted his fame, feeling, as he told his bride-to-be, considerable worry “that such attention may prompt me to assume individual merit for results which are entirely to be ascribed to the superintending blessing of a Divine Providence.” Rather than indulge in social gaieties, Franklin became involved in organizations such as the Naval and Military Bible Society, at whose annual meeting he related his story. For the rest of his life Franklin’s religious beliefs and practices had a strong evangelical tinge.

His Arctic experiences had changed Franklin, and never again would he exhibit the intense ambition of his earlier years. At first the change dismayed Porden – who was eager to see him play the roles of hero and author in her social world – because she feared he would expect her to share his evangelical zeal and perhaps to give up her literary career. Over time, she became more understanding about his social diffidence. To her friend and fellow writer Mary Russell Mitford, she explained that Franklin was “a man of sense and worth, but not a literary man – or, to speak more correctly, he reads and thinks much, but is not in the habit of communicating much of what he reads and thinks, except where he is very intimate.” After their marriage, Franklin gradually gained the acceptance of his wife’s literary friends.

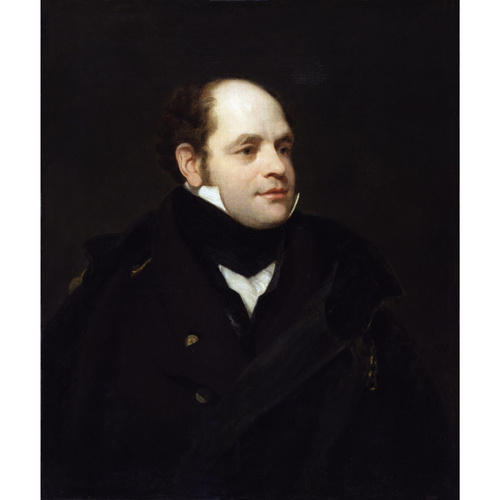

The birth of a daughter, Eleanor Isabella, on 3 June 1824 led to scenes of domestic happiness with, as Franklin later fondly recalled, “our little sprawler on the floor, and we reclining on the sophas.” Yet his wife’s health was steadily declining, although for many months the doctors failed to identify her disease as tuberculosis. Nevertheless, she emphatically insisted that he continue with his plans for a second expedition, and Franklin complied. She died on 22 Feb. 1825, only six days after he had once again sailed for the Arctic.

Parry’s expedition had proved that there almost certainly was a northwest passage. Accordingly, the Admiralty desired more information about the western Arctic coast. Even though the new expedition was broadly similar to the first in its geographical focus, because of Franklin’s careful planning and the support provided by the HBC (now merged with the NWC), no serious hardships would occur. Richardson and Back once again accompanied him; Hood’s place was taken by Edward Nicholas Kendall. Winter quarters were established at Fort Franklin on Great Bear Lake (N.W.T.) in the summer of 1825, and then in 1826 the expedition descended the Mackenzie River in specially constructed boats. From the mouth of the Mackenzie, Franklin and Back turned westward, while Richardson and Kendall went east to chart the coast between the Mackenzie and the Coppermine.

Again, Franklin was operating in conjunction with an expedition by sea. hms Blossom, commanded by Frederick William Beechey*, entered the Arctic from Bering Strait under orders to meet with Franklin if possible. Franklin’s boats were delayed by bad ice conditions and foggy weather; on 16 August, remembering the catastrophe of 1821, he reluctantly concluded that the “point beyond which perseverance would be rashness” had been reached. Although he felt “no ordinary pain” in doing so, Franklin gave the order to turn back. As he later learned, a boat sent out from the Blossom was then only 160 miles away.

A meeting with Beechey would have made Franklin even more of a popular hero than he already was, but among geographers and scientists the expedition was considered an unqualified success. The combined results of Franklin’s two ventures included the charting of more than 1,200 miles of coastline, plus important magnetic, geological, and zoological observations. Franklin returned to England in September 1827 and was knighted on 29 April 1829; other rewards included an honorary degree from the University of Oxford and the gold medal of the Société de Géographie de Paris.

Among the most charming letters Franklin ever wrote was his description of how he re-established a warm relationship with his three-year-old daughter, who of course had no memory of him: “I got her seated on the carpet with her [cousins] forming a circle round me and commenced a game of forfeits which depended on imitation which delighted the whole party, and Eleanor in particular to such a degree that our intimate acquaintance has been the result and we have been ever since amusing each other.” A concern for young Eleanor’s well-being may explain the promptness with which he began to court one of her mother’s friends, Jane Griffin. They were married just over a year after his return; sadly, Lady Franklin was not a success as a stepmother, but the relationship with her husband was a devoted one on both sides.

The government did not intend to sponsor further Arctic expeditions, and Franklin therefore sought a standard naval appointment. On 23 Aug. 1830 he became captain of hms Rainbow, stationed in the eastern Mediterranean. During this command, Franklin’s philosophy of leadership was a notable success: so harmonious was the spirit on board that the sailors nicknamed their ship Franklin’s Paradise. Originally based at Corfu (Kérkira, Greece), the Rainbow was ordered to the commercial port of Patras in the spring of 1832.

With the support of Britain, France, and Russia, Greece had recently gained its independence from Turkey; however, the country soon descended into a state of near-anarchy. Patras was occupied by a faction at odds with the provisional government, and Franklin was given the difficult task of maintaining order without the use of force. The British consul at Patras later wrote that the “worst and grossest excesses” of violence had been avoided only by Franklin’s “dignified calm.” This achievement had considerable political significance since the Russians were suspected of having fomented the disorder for their own purposes. King William IV rewarded him with the Royal Hanoverian Order, while from King Otho of Greece came the Order of the Redeemer.

Franklin returned to England at the end of 1833. Earlier that year, an overland relief party commanded by George Back had been sent out in search of John Ross’s long-absent expedition; both ventures had been privately organized. In 1836 Barrow, along with Franklin and Richardson, proposed a new naval endeavour to explore the remaining unknown coast between the Kent Peninsula, where Franklin had ended his outward journey in 1821, and Chantrey Inlet, discovered by Back (who had returned in September 1835). Franklin hoped to receive the command, but to his disappointment it was given to Back. He therefore accepted the offer of Lord Glenelg, the colonial secretary, to appoint him lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), then a convict colony.

Franklin arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on 6 Jan. 1837 and found that the elite among the free colonists were divided between the conservative adherents of the former governor, George Arthur*, and those who hoped for liberal reforms. By attempting to reconcile the two factions, Franklin merely gained the enmity of both. His chief opponent, John Montagu, had been Arthur’s secretary and was related to him by marriage. Montagu was undoubtedly an able man, with enlightened ideas on the management of convicts, but he also had a predilection for underhanded methods. During a long visit to England, Montagu viciously slandered Franklin in official quarters. In January 1842 Franklin dismissed him from his post. Once back in England, Montagu continued his campaign of vilification, with the result that Franklin was recalled by the new colonial secretary, Lord Stanley, in a letter that harshly censured his conduct. Copies of the letter were circulated in Van Diemen’s Land by Montagu’s friends. Nevertheless, many colonists were grateful to Franklin for his efforts to improve the educational system and to promote a range of scientific and cultural institutions. A large crowd turned out to cheer him as he left.

Franklin was back in England in June 1844, determined to wipe out the humiliation of Stanley’s letter. To his satisfaction, he learned that his reputation at the Admiralty had been sustained by reports from the officers of several scientific and surveying expeditions that had visited Van Diemen’s Land during his governorship. He was also interested by news that Barrow was promoting a new ship expedition to the Arctic Archipelago. However, Barrow’s plans were based on the optimistic and incorrect assumption that there was little or no land, and hence relatively open sea, along a southwesterly line from Barrow Strait to Bering Strait. Franklin did not share this belief. He knew that the expedition would encounter heavy ice and therefore would almost certainly take longer than Barrow claimed. Nevertheless, the chosen ships, Erebus and Terror, seemed likely to withstand even difficult conditions. Built to be exceptionally strong, they had been further reinforced for Sir James Clark Ross*’s 1839–43 expedition to the Antarctic, during which they had been the first ships to break through the belt of heavy pack ice north of the Ross Sea. Moreover, in 1845 Franklin insisted that they be equipped with auxiliary steam engines.

The command was offered first to James Ross but he declined it, possibly because of his recent marriage and possibly out of friendship for Franklin. Although he was almost 60, Franklin then pursued the appointment with great tenacity. His goal was not to add to his fame; rather, he wanted public proof that the Admiralty did not accept the Colonial Office’s view of him. He planned to let his officers carry out the significant exploratory and scientific work, reasoning that they would welcome the opportunity to advance their careers. His own role would be to maintain harmony and good health within the expedition. Knowing that the voyage would take two years or more, Franklin intended to supplement the rations with game whenever possible. He must have realized that, if an overland retreat became necessary, his age would make his own death certain; nevertheless, he chose to go.

The expedition, consisting of 129 officers and men, sailed on 19 May 1845. In September 1846 the Erebus and Terror were caught in heavy ice off the west coast of King William Island. Almost nothing was known about this island, which had been visited by Europeans only briefly during John Ross’s 1829–33 expedition. It proved to be an exceptionally poor hunting area. At first, success must have seemed close, for the ships were only about 100 miles from the continental coastline, where the explorers knew they would find a clear route to the west. However, the ice remained an insuperable barrier. The ships withstood the ice pressure, but without fresh game to eat the men began to weaken.

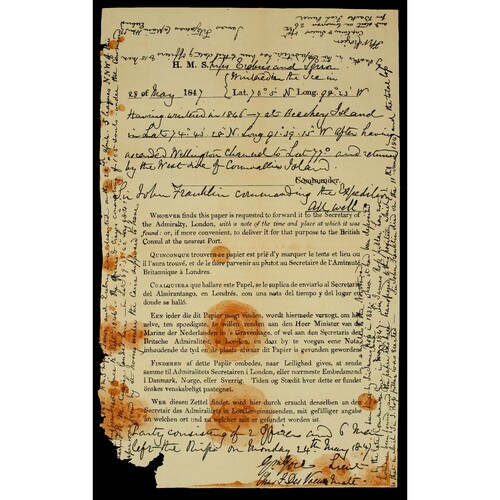

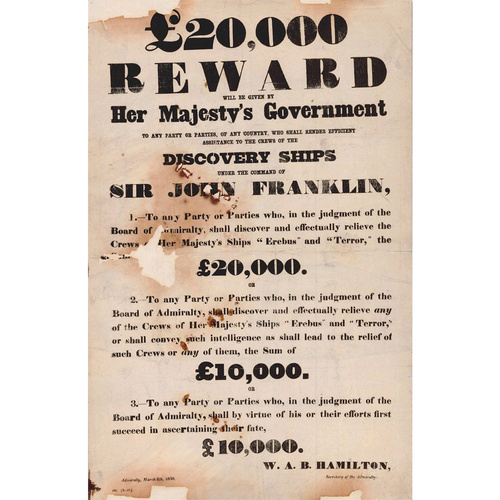

Franklin died on 11 June 1847. Neither the cause nor the exact place – whether on board ship or on land – was given in the document signed on 25 April 1848 by the second in command, Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier, at Victory Point on King William Island. In 1859 this document was found by members of a search expedition led by Francis Leopold McClintock*. It recorded that the ships had been abandoned and that the 15 officers and 90 men who remained alive would set off for the Great Fish (Back) River the next day. Presumably from there they would have tried to reach the HBC posts. There were no known survivors of the attempted retreat, during which some men resorted to cannibalism. The full details of their fate remain a mystery, despite a long series of 19th-century searches – many inspired by the tireless advocacy of Lady Franklin – and ongoing modern investigations. Oral accounts from Inuit who had encountered the dying explorers during the final stage of their retreat were collected in the 19th and early 20th centuries by John Rae*, Charles Francis Hall*, Frederick Schwatka*, and Knud Johan Victor Rasmussen*. In 2014 the wreck of the Erebus was discovered in Queen Maud Gulf, southwest of King William Island; two years later, the Terror was found near the island’s western coast.

The evidence collected by Rae, Hall, and Schwatka made the 19th-century British public well aware of the possibility that cannibalism had occurred during the expedition. However, the news had little effect on the regard in which Franklin and his men were generally held. Some commentators, following the lead of author Charles Dickens, vehemently denied that Inuit stories were reliable; others, citing the lack of physical evidence, believed that the matter could never be proved one way or the other; still others (and these perhaps voiced the most common response) accepted the fact of cannibalism but saw it as a tragic necessity, not a crime, and felt an intense compassion for the lost explorers’ suffering. One obscure poet, for example, expressed his wish to “draw with pity’ng hand a veil to hide / The last sad scene that clos’d their brave career.” Franklin featured in numerous 19th-century ballads and poems and was the subject of several admiring biographies. In the eyes of his biographers, Sir John was a hero because he embodied the virtues of stoicism, piety, and obedience to the call of duty, all of which were popularly associated with the officers of the Royal Navy.

In Canada, the idealization of Franklin as a national hero began in the early 20th century, just at the time when the first active assertions of Canadian sovereignty in the far north were being made. His status as an iconic figure in the Canadian imagination was most memorably expressed in the lyrics of Stan Rogers*’s “Northwest Passage” (1981), which is often described as an unofficial national anthem. Yet even at the time the song was written, both popular and academic historians were beginning to take a more critical view of Franklin, and his reputation has now deteriorated dramatically.

The reasons for this decline range from the trivial to the highly political. Franklin’s personality certainly lacked many of the characteristics that were expected of heroes in the late 20th century. Comments about his distinctly unheroic appearance – he was short and stocky and went bald in his 30s – abound in the literature (examples being the works of Pierre Berton*, Peter Steele, and Fergus Fleming, among others), and this aspect of the man, coupled with the frequent stodginess of his prose, led to the belief that his intelligence was not high. Some writers, such as Berton and Kenneth McGoogan, have insinuated that he was little more than the puppet of his clever and ambitious second wife. More seriously, Franklin’s interactions with northern indigenous people must now be considered from a post-colonial perspective. Unfortunately for Franklin, the views expressed in the 1930s by his very influential, but also notoriously untruthful, fellow explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson* were revived in the 1980s. Together with the rise of post-colonial criticism, Stefansson’s claims about the reasons for Franklin’s failures shaped the changing perceptions of academic historians. As a result, writers who admit that Franklin was a good and kindly man also assert that an exceptional degree of ethnocentricity and arrogance caused the disasters of his 1819–22 and 1845–48 expeditions.

Stefansson – who was eager to promote a belief in his own superiority to his predecessors – claimed that, owing to cultural prejudice, Franklin stubbornly refused to hunt like the Inuit, preferring canned English food to game or pemmican. But in fact Franklin was no more ethnocentric than most other explorers of his time, and considerably less so than some. During his two overland expeditions, Franklin subsisted mainly on game and pemmican (and, in the autumn of 1821, on lichen and maggots). In 1820 he wrote to his brother Willingham that he had become used to his new diet far more quickly than he expected. It was thanks to his advice that pemmican was taken on later ship expeditions. In 1845 over half a ton was included among the stores, and Franklin expressed his intention to hunt at every opportunity. The expedition was doomed not by ethnocentricity but by the lack of game on the west coast of King William Island – an area the Inuit avoided because of its barrenness.

As for Franklin’s intelligence, many of those who met him judged it initially by his appearance, but later realized their mistake. As his first wife’s niece observed, “I never knew any one improve so much on acquaintance.” Henry Crabb Robinson, a member of the Pordens’ literary circle, at first found Franklin disappointingly dull, but a year later described him as “a very excellent companion. His conversation [is] that of a man of knowledge and capacity, [and he has] decision of character combined with great gentleness of manners.” Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay] provided a similar account, writing that Franklin “argues not on what others say; he speaks of facts and listens as if learning from others in conversation. He speaks with slow, clear perception, with a dignified & impressive good sense, sound judgment & presence of mind.” Lady Franklin undoubtedly had a quicker intelligence than her husband, but his adroit diplomacy in Greece demonstrates that he was well able to succeed outside his usual naval sphere without her aid.

As a leader, the main point on which Franklin merits criticism is his failure to turn back soon enough on his first overland expedition. However, the nature of his orders and his awareness that Barrow expected daring rather than caution are mitigating factors. The standards by which Franklin judged his subordinates were rigid, but the men who met those standards found him an exceptional leader who, in Richardson’s words, gained not only their respect but also their affection by “the most conciliatory attentions to their feelings” and an “unremitting regard to their best interests.” His private secretary, Henry Elliot, agreed that because he identified himself so closely with “the interests and welfare of those over whom he was placed,” Franklin “won their love in an extraordinary degree.”

If Franklin was not among the greatest figures in the history of Arctic exploration, neither was he the incompetent blunderer described in so many recent books. He is perhaps best viewed as a man of middle-class origin who achieved success in a profession that favoured those with wealth and aristocratic connections, yet who was no mere careerist. His contribution to the knowledge of Canada’s coasts was second only to that of George Vancouver*. Franklin’s endeavours required intelligence, daring, and sheer driving ambition, but his benevolent personality and his deeply sincere religious beliefs raised his character to a level at which he was admired for far more than his accomplishments.

After the humiliating end of his governorship in Tasmania, Franklin decided that a new achievement was the only way to salvage his reputation. Before his first Arctic appointment, he had believed that his chances of worldly success were blocked by the Admiralty’s unjust refusal to reward his bravery at New Orleans. As a young man, he had therefore chosen to accept the risks of exploration, and he set out to make his name at all costs; in middle age, faced once again with injustice, he was determined to keep that name untarnished. Wounded pride and Barrow’s flawed plans sent him to his death. The enduring mystery of his last expedition’s fate then made him into a figure of near-mythical stature.

Sir John Franklin is the author of Narrative of a journey to the shores of the polar sea, in the years 1819, 20, 21, and 22 … (London, 1823), and Narrative of a second expedition to the shores of the polar sea, in the years 1825, 1826, and 1827: including an account of the progress of a detachment to the eastward, by John Richardson … (London, 1828). His correspondence can be found in Sir John Franklin’s journals and correspondence: the first Arctic land expedition, 1819–1822, ed. R. C. Davis (Toronto, 1995), and Sir John Franklin’s journals and correspondence: the second Arctic land expedition, 1825–1827, ed. and intro. R. C. Davis (Toronto, 1998).

Information on Franklin’s family can be found in “England, select births and christenings, 1538–1975”; “England, select marriages, 1538–1973”; “London, England, births and baptisms, 1813–1906”; and “UK, register of duties paid for apprentices’ indentures, 1710–1811,” available at www.ancestry.ca. For this biography baptismal records for his siblings, daughter, and niece Sophia Cracroft, the marriage record for his sister Isabella, and a record of duties paid for an apprenticeship by his father were consulted. A brave man and his belongings … (London, 1874) is usually attributed to Mary Anne Kendall, the eldest daughter of Franklin’s first wife’s sister, and the wife of explorer Edward Nicholas Kendall. But internal evidence suggests that it was written by her sister Eliza Margaret Jupp.

British Library (London), Add. mss 40666, 47768, 47769A, 56233. Derbyshire Record Office (Matlock, Eng.), D3311. National Maritime Museum, “The Flinders papers”: www.flinders.rmg.co.uk (consulted 14 Nov. 2016). Scott Polar Research Instit. (Cambridge, Eng.), ms 248 (Lefroy bequest). Thomas Bell, Winter evenings at home: a poem (Cambridge, 1856). Pierre Berton, The Arctic grail: the quest for the north west passage and the North Pole, 1818–1909 (Toronto, 1988). Janice Cavell, “Comparing mythologies: twentieth-century Canadian constructions of Sir John Franklin,” in Canadas of the mind: the making and unmaking of Canadian nationalisms in the twentieth century, ed. Norman Hillmer and Adam Chapnick (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2007), 15–45; “Lady Lucy Barry and evangelical reading on the first Franklin expedition,” Arctic (Calgary), 63 (2010): 131–40; “Representing Akaitcho: European vision and revision in the writing of John Franklin’s Narrative of a journey to the shores of the polar sea …,” Polar Record (Cambridge), 44 (2008): 25–34. R. J. Cyriax, Sir John Franklin’s last Arctic expedition: a chapter in the history of the Royal Navy (London, 1939; repr. West Sussex, Eng., 1997). R. C. Davis, “‘… which an affectionate heart would say’: John Franklin’s personal correspondence, 1819–1824,” Polar Record, 33 (1997): 189–212. Encyclopædia Britannica, “Sir John Richardson on Sir John Franklin”: www.britannica.com/topic/Sir-John-Richardson-on-Sir-John-Franklin-1994314 (consulted 25 July 2016). K. [E. Pitt] Fitzpatrick, Sir John Franklin in Tasmania, 1837–1843 (Melbourne, Aust., 1949). Fergus Fleming, Barrow’s boys (New York, 2000). E. M. Gell, John Franklin’s bride: Eleanor Anne Porden, born July 14th, 1795 – died February 22nd, 1825 (London, 1930). S. E. Grace, “Re-inventing Franklin,” Canadian Rev. of Comparative Literature ([Toronto]), 22 (1995): 707–25. William Jerdan, Men I have known (London, 1866). Shane McCorristine, “A manuscript history of the Franklin family by Sophia Cracroft (1853),” Polar Record, 51 (2015): 72–90. Ken McGoogan, Lady Franklin’s revenge: a true story of ambition, obsession and the remaking of Arctic history (Toronto, 2005). I. S. MacLaren, “The aesthetic mapping of nature in the second Franklin expedition,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 20 (1985–86), no.1: 39–57; “Tracing one discontinuous line through the poetry of the northwest passage,” Canadian Poetry (London, Ont.), no.39 (fall/winter 1996): 7–48. A. H. Markham, Life of Sir John Franklin and the north-west passage (London, 1891). Keith Millar et al., “A re-analysis of the supposed role of lead poisoning in Sir John Franklin’s last expedition, 1845–1848,” Polar Record, 51 (2015): 224–38. M. R. Mitford, The friendships of Mary Russell Mitford as recorded in letters from her literary correspondents, ed. A. G. L’Estrange (London, 1882). [George Ramsay, 9th Earl of] Dalhousie, The Dalhousie journals, ed. Marjorie Whitelaw (3v., [Toronto], 1978–82), 3. H. C. Robinson, Diary, reminiscences, and correspondence …, ed. Thomas Sadler (3v., London , 1869), 2. Peter Steele, The man who mapped the Arctic (Vancouver, 2003). H. D. Traill, The life of Sir John Franklin r.n. … (London, 1896). Glyn Williams, Arctic labyrinth: the quest for the Northwest Passage (Toronto, 2009).

Cite This Article

Janice Cavell, “FRANKLIN, Sir JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/franklin_john_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/franklin_john_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Janice Cavell |

| Title of Article: | FRANKLIN, Sir JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |