As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

ALLOUEZ, CLAUDE, priest, Jesuit, missionary, and explorer; b. 6 June 1622 at Saint-Didier-en-Forez; d. in the night of 27/28 Aug. 1689 in Miami territory, near Niles, Michigan.

Claude Allouez was 17 when, on 22 Sept. 1639, he entered the noviciate at Toulouse. He studied rhetoric (1641–42) and philosophy (1642–45) at the Collège in Billom, where he then became a teacher (1645–51); he studied theology at Toulouse (1651–55) and took his third probationary year at Rodez (1655–56); finally he was a preacher at Rodez until his departure for Canada.

The Journal des Jésuites notes his arrival at Quebec on 11 July 1658. At first he devoted himself to the study of the Huron and Algonkin languages. On 19 Sept. 1660, he left Quebec to take up an appointment as superior of the residence at Trois-Rivières. In 1663, he was named by Bishop François de Laval* vicar general of that part of the diocese of Quebec that today constitutes the central region of the United States. As a result of a misunderstanding he failed to set out in 1664, but was more successful the following year. This first trip, which is recalled for us by the Relation for 1667, was the most arduous of all, and it enables us to gauge the spiritual stature of Father Allouez. Scorned by the Ottawas, who did not want him among them, and abandoned on the shore of a lake as if he were a cumbersome dead weight, he took refuge in prayer: “In this abandoned state I withdrew into the woods, and, after thanking God for making me so acutely sensible of my slight worth, confessed before his divine Majesty that I was only a useless burden on this earth. My prayer ended, I returned to the water’s edge, where I found the disposition of that Savage who had repulsed me with such contempt entirely changed; for, unsolicited, he invited me to enter his Canoe, which I did with much alacrity, fearing he would change his mind.” The remainder of the voyage still held numerous hardships and humiliations in store for him; he was an awkward paddler, and was obliged to carry unaided over the 36 portages all his personal effects: some books, a portable altar, and a two-year supply of wine for masses.

On 1 October he arrived at Pointe du Saint Esprit, and made it the base for his apostolate. The humble birch-bark chapel that he erected there was the only one in existence west of Georgian Bay, and even west of Montreal. He gathered together the Christian Hurons who had not seen a Black Robe since the disaster of 1649. He taught the pagans of some ten nations who lived in those parts. In 1667, he went to Lake Nipigon to comfort the Christian Nipissings. He has the honour of having celebrated the first mass within the boundaries of the present diocese of Fort William. That same year, and again two years later, in 1669, he went down to Quebec in search of apostolic workers. But he did not linger there, and a few days after his arrival, he was already on the way back.

When, in 1671, Daumont de Saint-Lusson took possession of the expanses of the west in the name of the king of France, it was Father Allouez who delivered the address for the occasion. No one was better qualified to do so, both because of the prestige he enjoyed among the Indian nations and because of the fluency with which he spoke their languages and the way in which his kind of eloquence delighted his hearers. Some idea of Father Allouez’s achievements can be had if one considers that he scoured in every direction the region around the Great Lakes: Huron, Superior, Erie, and Michigan; 3,000 miles of wild country throughout which was scattered his nomadic flock: 23 nations of differing races, languages, and customs, according to the testimony of his superior, Father Claude Dablon. It is estimated that in the course of his 24 years of missionary apostolate, he personally baptized some 10,000 neophytes.

Father Allouez’s written work is extensive and important. The Relations for the years 1667 to 1676 have preserved for us considerable extracts from his diary. One document however has been attributed to him which is not entirely from his hand. In his Établissements et découvertes des Français, Pierre Margry, on the authority of Father Dablon, published a document entitled “Sentiments du P. Claude Allouez.” These notes, in Father Allouez’s handwriting, were found in his papers after his death and sent to the superior at Quebec. The latter attributed them to Father Allouez and this attribution has persisted until the present. A careful study, however, allows us to question the attribution to Father Allouez of this work in its entirety. Almost all these notes are found, at times word for word, in the “Divers sentiments et avis” that conclude the Relation for 1635. Father Allouez had copied this document in his own hand, as it was important for its spiritual and apostolic value; and he thus had as his model to the very end of his life the portrait of the ideal missionary. Father Dablon can be forgiven for not having had a clear memory in 1690 of these texts from the Relation for 1635. But his mistake of attribution is the finest tribute he could pay to Father Allouez: that of having been the living confirmation of the essential characteristics of the perfect missionary.

A contemporary of and co-worker with those apostolic giants Jacques Marquette and Claude Dablon, Claude Allouez is not their inferior in any respect. It has even been asserted, and this is our view, that he was the greatest missionary of the generation following that of the holy martyrs. “In Wisconsin,” writes Father Gilbert Garraghan, “the earliest missionary endeavors on behalf of the Indian gather around the name of Claude Allouez. On Chequamegon Bay near the modern Ashland, at De Pere, and at various points in the interior of the state, he set up mission-posts that became so many starting-points for the civilizing influences that he sought to bring to bear upon the children of the forest. His appointment to the post of vicar general by saintly Bishop Laval, July 21, 1663, marked in a way the first organization of the Church in mid-America. From his pen came the earliest published account of the Illinois Indians, who were to give their name to the future state. No other figure at the dawn of Wisconsin history rises to a more commanding height. If the name of Jacques Marquette stands apart in the fervor of its appeal to sentiment and the historical imagination, the name of Claude Allouez deserves to be remembered as that of the first organizer of Catholicism in what is now the heart of the United States.”

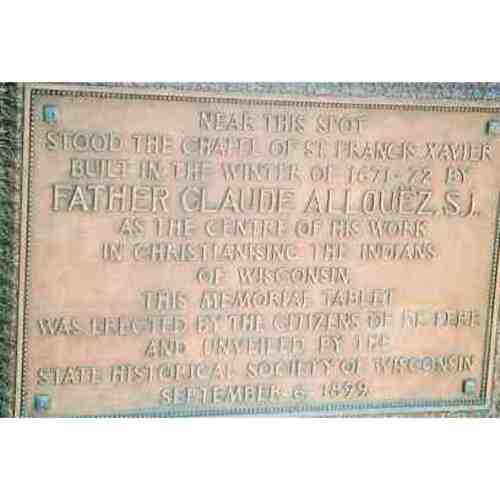

In the United States, and especially in Wisconsin, Father Allouez’s memory has always been venerated. In 1899 the Wisconsin Historical Society erected a monument to him at De Pere. It is of interest to note that the then secretary of the Society was Reuben Gold Thwaites, the peerless editor of the collection of Jesuit Relations and allied documents.

Découvertes et établissements des Français (Margry), I, 58–72. JR (Thwaites), passim. JJ (Laverdière et Casgrain). Campbell, Pioneer priests, I, 119, 121, 147–64. Delanglez, Jolliet. G. J. Garraghan, The Jesuits of the middle United States (3v., New York, 1938), I, 3–4. Francis Nelligan, “The visit of Father Allouez to Lake Nipigon in 1667,” CCHA Report, 1956, 41–52. Léon Pouliot, “La part du P. Claude Allouez dans les ‘sentiments’ qui lui sont attribués,” RHAF, XV (1961–62), 379–95. Rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle, II, 353f.

Cite This Article

Léon Pouliot, “ALLOUEZ, CLAUDE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/allouez_claude_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/allouez_claude_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Léon Pouliot |

| Title of Article: | ALLOUEZ, CLAUDE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |