Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ULOQSAQ (Uluksuk), Copper Inuit hunter, shaman, and convicted murderer; b. c. 1887 in the Coppermine district, N.W.T., son of Anerak; he had two wives, Kukiluka (Kuilukak) and Koptana; d. 24 Sept. 1929 at the settlement of Coppermine (Kugluktuk, Nunavut).

The date of Uloqsaq’s birth is not known, but at his trial in 1917 it was stated he was about 30. The anthropologist Diamond Jenness*, at whose camp he had stayed in November 1915, reported that he was a prominent shaman who had purchased his powers from a shaman in Bathurst Inlet and could transform himself into a bear, a wolf, or even a European. His guiding spirit appeared as a dog. In March 1915 he had been asked by the Inuit of the Dolphin and Union Strait region to drive away an evil spirit which threatened to destroy them; his dog-spirit drove the evil one out and killed it in the snow. He related to Jenness that as a shaman he had lived underwater for days, brought dead men to life, seen dogs with four tails and white men with mouths on their chests, and turned men and women into wolves and musk oxen.

Late in 1913 two Oblate priests, Jean-Baptiste Rouvière and Guillaume Le Roux, were travelling north towards Coronation Gulf with the intention of winning the Inuit of the Coppermine River region over to Christianity. They had heard that a Church of England missionary was heading there “to sow tares in our fields,” and wished to forestall him; the “race for souls” was intense in this era. Sometime in November, near the mouth of the Coppermine, the priests met Uloqsaq and another hunter, Sinnisiak, who agreed to go with them to help with the sleds in return for payment in traps. But when Le Roux, or Ilogoak as he was called, became impatient and angry with the two Inuit – he was apparently short-tempered – they decided that the priests meant to kill them. At Sinnisiak’s urging, the Oblates were shot and stabbed, and part of their livers were eaten for ritualistic reasons.

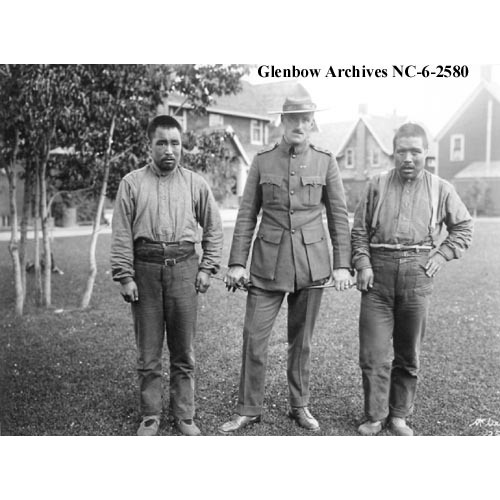

When news of the killings became known to the authorities, a Royal North-West Mounted Police patrol headed by Inspector Charles Deering La Nauze and Corporal Wyndham Valentine Bruce was sent to investigate. The two Inuit surrendered peacefully in May 1916, and willingly gave complete statements. Uloqsaq recalled: “I wanted to speak; Ilogoak put his hand over my mouth. . . . Ilogoak pointed the gun at us. I was afraid and I was crying. . . . Sinnisiak said to me ‘We ought to kill these white men before they kill us.’”

This was the second case in which Inuit had killed whites in the Canadian Arctic. In June 1912 two explorers, Harry V. Radford and Thomas George Street, had been murdered in the same area for much the same reason. The government went no further than a warning then, but in the case of the priests it felt some example had to be made. In August 1917 Sinnisiak, considered the chief perpetrator, was tried in Edmonton for the murder of Rouvière, but was acquitted, probably because the jury thought the priests’ foolish treatment of the accused had led to their deaths. Anti-Catholic prejudice may also have been a factor in this acquittal. Both men were then taken to Calgary and, in late August, tried and found guilty of killing Le Roux, the first two Inuit to be convicted of murder by Canadian courts. Their death sentences were immediately commuted to life imprisonment at the police post at Fort Resolution, N.W.T. They were kept there under minimum security for two years, and in 1919 they travelled with the police to help establish a new detachment at Tree River, on the Arctic coast. In 1922 they were permitted to return to their people.

At one time it was believed that Uloqsaq was killed in 1924 by another Inuk because living with Europeans had made him arrogant and bullying, a story that arose out of confusion over Inuit names. Uloqsaq was in fact living at Bernard Harbour in the late 1920s. In 1928 Anglican bishop Archibald Lang Fleming* found him there, destitute and unable to hunt because he had contracted tuberculosis of the spine. He sent Uloqsaq to the church hospital at Aklavik, but since it was unable to provide chronic care, he was taken home to Coppermine in the summer of 1929 on the Hudson’s Bay Company ship Baychimo. Uloqsaq died there that September, one of the many Inuit who succumbed to the terrible epidemic of tuberculosis then sweeping the region.

Can., Parl., Sessional papers, report of the Royal North-West Mounted Police, 1916. R. G. Moyles, British law and Arctic men: the celebrated 1917 murder trials of Sinnisiak and Uluksuk, first Inuit tried under white man’s law (Saskatoon, 1979). W. J. Vanast, “The death of Jennie Kanajuq: tuberculosis, religious competition and cultural conflict in Coppermine, 1929–31,” Inuit Studies (Quebec), 15 (1991), no.1: 75–104. George Whalley, The legend of John Hornby (Toronto, 1962).

Cite This Article

William R. Morrison, “ULOQSAQ (Uluksuk),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/uloqsaq_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/uloqsaq_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | William R. Morrison |

| Title of Article: | ULOQSAQ (Uluksuk) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |