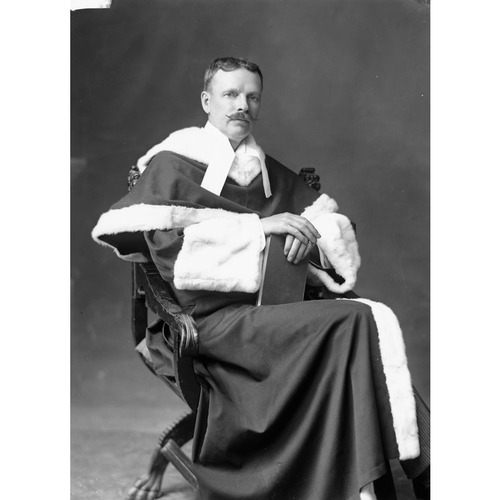

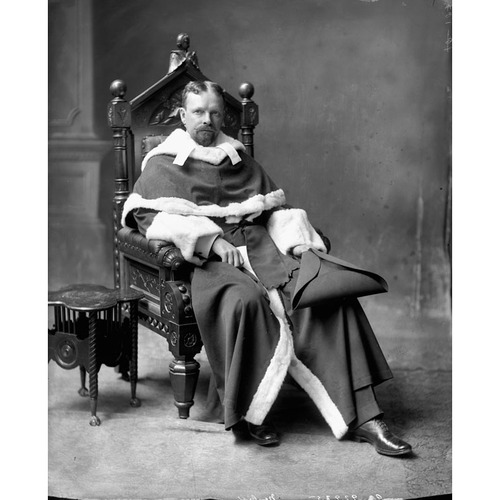

NESBITT, WALLACE, lawyer and judge; b. 13 May 1858 near Holbrook, Upper Canada, son of John W. Nesbitt and Mary Wallace; m. first 1887 Louisa Andrée Plumb, née Elliott (d. 1894); they had no children; m. secondly 1898 Amy Gertrude Beatty, and they had a son; d. 7 April 1930 in Toronto.

Wallace Nesbitt’s father, a Scot, immigrated to Canada in 1837 with his Irish wife and settled on a farm in Oxford County. The youngest of 11 children, Wallace was raised there. After attending Woodstock College, he was articled as a law clerk and studied at Osgoode Hall in Toronto, where he won prizes. Following his call to the bar in Hilary term 1881, he practised with his brother John Wallace in Hamilton. In 1883 Britton Bath Osler* persuaded him to join his Toronto firm, McCarthy, Osler, Hoskin, and Creelman. During his nine years there Nesbitt acted in such notable cases as the suit between the Canadian Pacific Railway and the contracting company of James Conmee*. In 1887 he married the New Orleans-born widow of his one-time partner Thomas Street Plumb, and became the stepfather of two young children.

In 1892 Nesbitt left McCarthy Osler for the firm of William Henry Beatty*, which largely served the Gooderham and Worts business empire. The addition of Nesbitt (who would be named a federal qc in 1896), George Tate Blackstock, William Renwick Riddell*, and Hugh Edward Rose laid the foundation for the partners’ emergence as a top litigation group. By 1898 (the year he married Beatty’s daughter), Nesbitt had been involved, according to Henry James Morgan*, in “many important suits” and was “singularly successful” as a jury lawyer. In 1900 he represented the Canadian Copper Company in its opposition to duties on nickel exports [see Andrew Trew Wood*], and within a year he had aligned himself professionally with private companies in the emerging battle over the public ownership of hydroelectric development in Ontario. By 1902, with Beatty spending much of his time running the Gooderham and Worts businesses, David Fasken had assumed the management of the law firm. This shift does not seem to have sat well with many of its members, and they began to resign. The first to leave was Nesbitt.

On 16 May 1903, at age 45, he was named by Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* to the Supreme Court of Canada. The appointment represented a break with the patronage appointments of the day since he was both a Conservative and a sound choice. As James G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan say in their history of the court, “Nesbitt had an outstanding reputation as counsel, and his nomination . . . was widely acclaimed.” Although he did not have time to produce a significant body of judgements – he would sit for only two years – his decisions, a number of them involving cases of negligence, reflected careful analyses. The support he often won from his fellow judges suggests that he had the respect of the bench, but it was not always mutual – some of his dissents were very critical of the majority.

On 4 Oct. 1905 Nesbitt resigned to return to private practice. He was the second justice to leave that year, Albert Clements Killam* having gone to the Board of Railway Commissioners. Their departures could indicate some unhappiness within the court, but Nesbitt stated simply that he was leaving “for reasons purely private.” Perhaps he wanted to assist his father-in-law, who was having a difficult year. George Gooderham* had died in May and Beatty had left his firm to assume the direct leadership of the Gooderham and Worts businesses. Beatty also found himself before the courts over the ownership of some property in northern Ontario, and Nesbitt may well have been asked to come to his aid; he would appear in court on Beatty’s behalf in December. Even before his resignation, he had joined Beatty in business ventures. In June 1905, for example, both were appointed to the board of the Canadian Niagara Power Company, with Beatty becoming president.

Instead of returning to the Beatty firm, however, likely because of the rift with Fasken, Nesbitt rejoined McCarthy Osler and resumed his career as a trial and corporation counsel. One biographical account would note that as a former, and highly regarded, Supreme Court judge, “he took up a unique and enviable position which brought him a large clientèle and ultimately considerable wealth.” He acted in many high-profile cases, for example in opposition in 1912 to Ontario Hydro’s powers of expropriation and as the nominee in 1918 of Mackenzie, Mann and Company and the Canadian Bank of Commerce in the Canadian Northern Railway arbitration [see Sir William Mackenzie]. No stranger to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain, which he steadfastly defended as Canada’s final court of appeal, he continued to argue there, appearing, among other causes, on behalf of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company in the coal case of 1908, for the dominion in a dispute over Quebec marriage law in 1912, and in the long-running reference over the constitutional authority of provinces to incorporate companies with interprovincial or international operations. In 1924 he was named to a commission to consider the Quebec act that had placed the education of Jews under Protestant school boards. In some situations, his corporate and legal interests overlapped; as president of Canadian Niagara Power, he had given way to Ontario Hydro and reached a settlement in 1916.

Since his early years in practice, Nesbitt had been active in the institutions of the legal fraternity. In 1885–86 he was president of the Osgoode Legal and Literary Society. First elected a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1906, he became its treasurer (the highest position in the Ontario bar) in 1927; two years later he personally gave it $10,000 in securities to support legal education. In 1928–29 he served as president of the Canadian Bar Association.

Nesbitt found time publicly to address matters of current interest. An opponent of reciprocity with the United States in 1911, he spoke eloquently of the need to strengthen Canada’s imperial ties with Britain and its other colonies. One means, he had argued in 1910, was the formation of a permanent imperial council. A Presbyterian, freemason, and keen golfer, clubman, and fisherman, he also took a strong interest in the St John Ambulance Association, which made him a knight of grace for his service as president of its Ontario Council. The tall, bespectacled lawyer possessed a “wide knowledge” of English literature and, in the estimate of British chancellor Lord Sankey, a “genius for friendship.”

In the summer of 1929, while at his cottage on Wawataysee Island in Georgian Bay, Nesbitt suffered a stroke from which he never fully recovered. He died the next year at his home on Warren Road in Toronto and was buried in St James’ Cemetery.

Wallace Nesbitt assisted W. H. Beatty in the preparation of The Boards of Trade General Arbitrations Act (1894) and rules of the Toronto Chamber of Arbitration: with notes and suggestions as to the conduct of a reference (Toronto, 1894). On his own, Nesbitt published The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council; a paper presented to the thirty-second annual meeting of the New York State Bar Association, held at the City of Buffalo, on the 28th and 29th of January, 1909 ([Toronto?, 1909?]), Reciprocity: an address delivered before the Canadian Club, Montreal, December 12th, 1910 ([Montreal?, 1910?]), and “Our country and its future”: speech . . . at the annual banquet of the Chatham Board of Trade, January 9th, 1911 ([Chatham, Ont.?, 1911?]).

AO, RG 22-305, nos.10412, 64362; RG 80-8-0-180, no.22220. Globe, 8 April 1930. Christopher Armstrong, The politics of federalism: Ontario’s relations with the federal government, 1867-1942 (Toronto, 1981). Beatty v. McConnell (1905), Ontario Weekly Reporter (Toronto), 6: 882-85. Canada Law Journal (Toronto), 17 (1881): 99. Canadian annual rev. Canadian Bar Assoc., Proc. (Toronto), 15 (1930): 24-25. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Curtis Cole, “McCarthy, Osler, Hoskin, and Creelman, 1882 to 1902: establishing a reputation, building a practice,” in Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty et al. (8v. to date, Toronto, 1981-?), 4 (Beyond the law: lawyers and business in Canada, 1830 to 1930, ed. Carol Wilton, 1990): 149-66; Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt: portrait of a partnership (Toronto, 1995). G. F. Henderson, “Wallace Nesbitt, k.c.,” Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 8 (1930): 283-84. “The late Hon. Wallace Nesbitt,” Manitoba Bar News (Winnipeg), 2 (1929-30), no.9: 4. J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution ([Toronto], 1985). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), 1: 380.

Cite This Article

C. Ian Kyer, “NESBITT, WALLACE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nesbitt_wallace_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nesbitt_wallace_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. Ian Kyer |

| Title of Article: | NESBITT, WALLACE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |