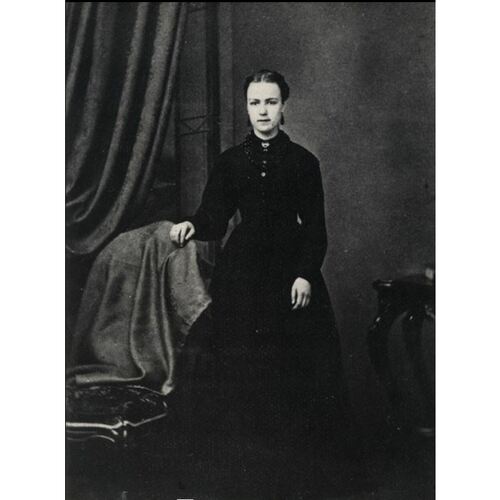

![Laure Conan (pseudonyme de Marie-Louise Félicité Angers). Date: [Vers 1870]. http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3107464

Original title: Laure Conan (pseudonyme de Marie-Louise Félicité Angers). Date: [Vers 1870]. http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3107464](/bioimages/w600.12896.jpg)

Source: Link

ANGERS, FÉLICITÉ (baptized Marie-Louise-Félicité), known as Laure Conan, novelist, biographer, journalist, and playwright; b. 9 Jan. 1845 in La Malbaie, Lower Canada, daughter of Élie Angers, a blacksmith, and Marie Perron; d. unmarried 6 June 1924 at Quebec.

Félicité Angers was one of a family of 12 children, of whom six survived to adulthood. The Angers had owned a general store and run the post office in La Malbaie since the end of the 18th century. All the children would get their higher education at Quebec. During her three years with the Ursulines, from 4 Oct. 1859 to 1 July 1862, Félicité was already attracting attention because of her literary talents. There were so many Irish Catholic girls at the convent that she lived in a naturally bilingual environment. She became fluent in English and in German as well. In 1861 she completed her literature course and won a number of prizes. The following year she was among five pupils enrolled in the higher class, which was optional and open only to the most gifted. She would be the only one to pursue a literary career. Some of her compositions and those of her close friend Suzanne Lauretta Stuart were published in the cahier d’honneur of the Papillon Littéraire, an academy whose director at the time was Abbé George-Louis Le Moine, the chaplain to the Ursulines. Le Moine criticized Félicité’s earliest writing for its “almost total lack of punctuation” and its “style” which he thought “rather stiff.” Nevertheless, Félicité’s essays were among his favourites. Their historical and religious themes, featuring heroes whose strong personalities and tragic or patriotic actions were described in minute and intimate detail, clearly revealed what would characterize the form and content of the future Laure Conan’s work.

When she returned home in the summer of 1862, Félicité apparently began seeing Pierre-Alexis Tremblay*, a surveyor and native of La Malbaie, who was then 34 years old. In January 1865 he became the mla (of a Liberal stripe) for the united ridings of Chicoutimi and Saguenay. The romantic relationship ended sometime between 1867 and 1870, the year in which Pierre-Alexis married Mary Ellen Connolly. On 2 March 1871 Félicité had a mystical vision, another experience that would remain deeply engraved in her memory. “In receiving absolution, I received the application of the blood of Jesus Christ in the most tangible manner,” she would write on 21 Feb. 1879 to her close confidante, Mother Catherine-Aurélie du Précieux-Sang [Caouette*], the founder of the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood in Saint-Hyacinthe.

Félicité would never recover from the break-up of her romance with Pierre-Alexis. Thinly veiled references to this relationship can be found in several of her novels, where she would reveal herself through the literary devices of letters and personal diary. According to a number of critics, the man she had loved and lost was the root cause of the world-weariness, low spirits, isolation, and bitter and fatalistic tone that would be found in the novelist’s work and that, despite her use of a pseudonym, would lay bare her private and public life. Some researchers ascribe the parting of the lovers to a vow of chastity that Pierre-Alexis is thought to have taken in his youth; Félicité is believed to have refused her fiancé’s offer of an unconsummated marriage. Mother Catherine-Aurélie’s letter to Félicité dated 24 Jan. 1880 suggests quite the opposite. “Your virginal dream has not then as yet disappeared from your soul and your desires, my dear Félicité? I must admit that I am afraid the Friend who would suit you might be hard to find, but what I feel certain is that it is quite simply a divine Friend who might well meet your needs.” Félicité would be unequivocal in her response. On 11 Nov. 1884 she wrote: “I have not the slightest inclination for the religious life – not the slightest for marriage either – that great Sacrament has no attraction for me. . . . Ah how I would suffer in it!”

In the space of a few years, death robbed Félicité of those closest to her: her father in 1875 and her mother in 1879. With the death of Pierre-Alexis, also in 1879, she lost all hope. She did, however, put together a network of acquaintances who would play a decisive role in her future. In the fall of 1877 and the winter of 1878 she had visited the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood, and thus met two women who would be her main correspondents, the founder of the community (letters from 1878 to 1905) and Sister Marie de Saint-François-Xavier, née Sophronie Boucher (letters from 1879 to 1918). In 1879 her brother Charles was a classmate and close friend of the future historian Thomas Chapais* when they were both studying law at the Université Laval at Quebec. They often arranged to meet at the presbytery of Narcisse Doucet, the curé of La Malbaie, where they joined other men of intellect, including Abbé Apollinaire Gingras, the curé of Saint-Fulgence, who would publish Au foyer de mon presbytère at Quebec in 1881, Abbé Paul Bruchési*, a young man spending his summer holidays there, and Félicité’s older brother Élie Angers, a notary who wrote poetry when the spirit moved him and who had been a friend of Octave Crémazie*. Félicité also participated in the group’s meetings. Chapais and Bruchési would become her chief patrons. Around 1880 Félicité discovered Father Louis Fiévez, a Redemptorist and brilliant preacher attached to the basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, her favourite place of pilgrimage. He would have to keep constantly reassuring her as to her choice of a literary vocation. Bruchési and Fiévez would serve as her spiritual directors, replacing Mgr Joseph-Sabin Raymond*, with whom she had kept up a correspondence until 1879.

It was in this context that Félicité Angers, at the age of 33, published her first work, a short story entitled “Un amour vrai,” which appeared in the Revue de Montréal in 1878 and 1879. She used the pen name of Laure Conan, apparently after reading the works of Zénaïde Fleuriot, which contain a reference to Conan III, Duc de Bretagne. Since this “first effort has been noticed” and since “I absolutely must have activities that will absorb me [and] rescue me from the bitterness of my regrets,” as she ventured to confide in Mother Catherine-Aurélie on 21 Feb. 1879, “I would like to begin writing. . . . If possible, I would like to use this talent to earn my livelihood.” “Could you not,” she beseeched her, using the English endearment “sweetest mother,” “suggest a subject for a short story or a novel?” Now an orphan, Félicité was in a precarious financial position that year, living with her brother Élie and her then unmarried sisters, Marie-Marguerite (nicknamed Mary) and Adèle (who would marry in 1884). Except for marriage and the religious life, she would consider every possible means of supporting herself: taking over the post office, which Élie had run into debt, buying lottery tickets, praying, signing “partnership agreements” with God (“Once my debts are paid off,” she would write to Mother Catherine-Aurélie on 11 Nov. 1884, “I will give him half the profits”), and writing. Only this last activity would enable her to earn a living, a rare privilege for writers of her time; she was the sole instance of a French Canadian woman doing so in this field. From then on literary works would follow in rapid succession.

“Angéline de Montbrun” appeared in the Revue canadienne (Montréal) in 1881 and 1882. From 1881 to 1919 this periodical would publish 38 articles (biographies and instalments of novels) by Laure Conan. The novelist was to bring out all her works, with but few exceptions, first in at least one periodical and then in book form. In 1882, eager to take advantage of her success with “Angéline de Montbrun” by publishing it as a book, she sought Bruchési’s advice. He recommended that she contact Henri-Raymond Casgrain*. In a letter addressed to him on 4 March 1884, she referred to him as “the father of Canadian literature.” She travelled to Rivière-Ouelle in 1882 and again in 1883 to visit her new patron. “Necessity alone has given me the extraordinary courage to get myself published,” she confessed to him on 9 Dec. 1882. Everything possible was done to help the young novelist and make her better known. Casgrain was the only man who really took her financial and intellectual situation seriously. He sought the support of Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* and Sir Hector-Louis Langevin* to get her a position as a librarian at the archives in Ottawa, but in vain. On 9 Oct. 1883, under the signature of Un Comité de Dames, Casgrain praised and promoted “Angéline de Montbrun” in the Quebec newspaper Le Courrier du Canada, since, as he had said to Chauveau the day before, “[women] must try to achieve their literary success in our country, just as men have had theirs.” He managed to get Léger Brousseau* to publish the book, for which he himself wrote the preface, and to persuade Louis Fréchette*, Narcisse-Henri-Édouard Faucher* de Saint-Maurice, Chauveau, and the poet Alfred Garneau to write reviews of it. He did not succeed, however, in inducing Laure Conan to accept the part of his preface in which he revealed her true identity. “I have never allowed my name to be associated with my pseudonym,” she told him on 14 Jan. 1884, after asking Garneau to intercede with him on her behalf. The hard-fought battle over her pseudonym led to a coolness between these two headstrong individuals, and they apparently exchanged no more letters from the time the book appeared, in 1884, until a few weeks before Casgrain’s death in 1904.

Laure Conan was now definitely launched on her career. During a visit to Europe in 1884–85, Bruchési even took the opportunity to bring her to the attention of the writers Pauline de La Ferronnays (who wrote using her married name, Mrs Augustus Craven), Xavier Marmier, and René Bazin, with whom she would exchange a few letters. Because the intimist genres encouraged critics to reveal her identity against her will, and also because the subject of “À travers les ronces,” a story published in the Quebec magazine Les Nouvelles Soirées canadiennes in 1883, had struck her as “tedious and unrewarding” (as she confessed to Sister Marie de Saint-François-Xavier on 20 April of that year), she now turned instead to historical novels and biography. Endowed with a prodigious memory, she could recite passages from the many authors she had read and quote them in her works. Her reading included Dante, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Jonathan Swift, Goethe, Alphonse de Lamartine, Victor Hugo, and Eugénie de Guérin, as well as the Bible and the church fathers. The Canadian works she referred to included those of Samuel de Champlain*, François-Xavier Garneau*, Crémazie, and Edmond de Nevers [Boisvert*], as well as the Jesuit Relations. In fact, critics would accuse her of alluding to these numerous sources of inspiration too frequently in her stories.

To document the work that would become À l’œuvre et à l’épreuve, which tells the story of the martyr Charles Garnier*, Laure Conan approached historians Louis-Édouard Bois*, Alfred Duclos De Celles (through Alfred Garneau’s daughter Élodie), and Hospice-Anthelme-Jean-Baptiste Verreau*, as well as the Jesuit Joseph-Édouard Désy, but with little success. Since she could no longer depend on Casgrain, she herself began looking for a publisher and negotiated her financial terms. Offering her new novel to Mgr Thomas-Étienne Hamel for Le Canada français, a periodical published by the Université Laval at Quebec, she pointed out on 17 Feb. 1889: “Our poor Crémazie wanted Canadian writers who did their work carefully to be paid four or five dollars per page – regular size. This is what I would like for my novel.” Through Father Désy, she eventually got À l’œuvre et à l’épreuve printed at Quebec in 1891. It was a novel for which the French government would award her the Ordre des Palmes Académiques in 1898. An edition commissioned by Marguerite d’Orléans, Princess Czartoryska, brought out in Paris in 1893, would give her a good deal of trouble because of the printer’s refusal to pay the royalties in full. She encountered the same kind of problem in 1897, when the publishers J.-A. and M.-E. Leprohon marketed a pirated edition of Un amour vrai in Montreal under the title Larmes d’amour. She sued for damages, but unfortunately lost the case, which was closed in 1899.

At the time when Laure Conan began a career in journalism, after 1890, the mass-market newspapers served various interests (political, religious, social, and cultural) and readerships. Women were taking an increasingly important place in this field and making their contribution to it in many different ways. For example, in the December 1893 issue of the Montreal paper Le Coin du feu, she replied to Joséphine Dandurand [Marchand]: “I confess to you, madam, that it seems to me not very desirable for us [to have] the right to vote. But, if it were ever granted to us – and this is a matter I care little about – I am convinced that women could hardly make worse use of it than men [do].” It was only rarely, however, that the writer publicly expressed her political beliefs or her opinion on women’s demands. As for her religious beliefs, that was quite another matter.

From 1894 to 1898 Laure Conan, who was living in Saint-Hyacinthe at the time, edited a periodical entitled La Voix du Précieux Sang, for $800 a year, plus room and board. She would contribute 90 articles to it, mostly religious biographies (including those of St Catherine of Siena, Jeanne Mance*, St Perpetua, St Felicity, and the Abbé de Rancé). In 1913 these would be collected into a volume brought out in Montreal under the title Physionomies de saints. In 1896–97 and again from 1903 to 1906 she contributed 20 biographies to Le Rosaire et les autres dévotions dominicaines (shortened in 1902 to Le Rosaire), a periodical published by the Dominicans of Saint-Hyacinthe. These articles and others (including a biography of Louis Hébert*) would make up a volume entitled Silhouettes canadiennes, which came out at Quebec in 1917 and again in 1922. From 1902 to 1907 Laure Conan wrote essays for the Montreal magazine Le Journal de Françoise [see Robertine Barry*], including in 1903 “La correspondance de Mme Julie Lavergne” – Lavergne was a French woman of letters whom she reputedly knew – and in 1904 “Un exemple aux femmes malheureuses en ménage” and “Vos morts,” as well as stories and legends for children. Pieces by her can also be found in several other periodicals. She contributed 195 articles in all to Quebec publications.

In 1900 Laure Conan wrote an account of “Nos établissements d’éducation” for Women of Canada: their life and work, a collection prepared for the universal exposition in Paris and very probably published in Montreal, where she brought out (in serial form and as a book) L’oublié, a novel intended “to shed light on . . . the beauty [and] the poetic grandeur of Montreal’s early days,” as she had told Verreau on 17 April 1899. But she was growing tired. “Mentally, I live in a terrible and very painful state of isolation,” she confided to Abbé Henri-Arthur Scott on 1 Dec. 1900. Yet she had many faithful correspondents, even outside the country. It was, indeed, her French network that would arrange for her to receive a Prix Montyon from the Académie Française for L’oublié in June 1903. Joseph Lavergne (son of the late Julie Lavergne) and Hector Fabre* (the representative in Paris of the provincial and federal governments) in all likelihood had been behind this movement to recognize the first woman in French Canada to pursue a literary career. From then on the novelist’s works were more widely circulated in schools, in both Quebec and Ontario. But Laure Conan had to endure many humiliations, in comparison, for example, to Louis Fréchette, who had been awarded a Prix Montyon in 1880. “Such gentlemen get everything, and I will always be the victim if you do not honour me with your patronage,” she wrote to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* on 18 April 1904. On 6 April she had pointed out to him, “If I were a man, I would be treated very differently.” In 1907, following the success of L’oublié, the novelist decided, on the advice of Father Edmond Rottot, to write a dramatized version of it, Aux jours de Maisonneuve.

Towards the end of her life, Laure Conan returned to intimist fiction. The open diary of a woman alienated by the emptiness of her life provides the framework for L’obscure souffrance and La vaine foi. The first was serialized in the Revue canadienne in 1915 and 1919 and published as a book at Quebec in 1919. The second came out in Montreal in 1921 in La Revue nationale and in book form. These works are not really novels, but rather collections of selected thoughts, bringing together the torments of a woman who, like Félicité Angers herself, was profoundly affected by existential, romantic, and religious crises. The writing is concise and strong, marked by a maturity lacking in Angéline de Montbrun. In a letter to her on 29 Feb. 1920, Albert Lozeau commented on the “high moral value” of the thoughts expressed by Faustine in L’obscure souffrance. From 1910 to 2 July 1923 the novelist stayed regularly at the institute of the Little Daughters of St Joseph on Rue Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes in Montreal. In the fall of 1920 she sold her possessions at auction and left the family home. She spent the summers of 1922 and 1923 in Saint-André, near Kamouraska, with the Sisters of Charity, where no doubt she frequently saw her dear friend Thomas Chapais, with whom she had secretly fallen in love. She busied herself with her publications and the production of her play, Aux jours de Maisonneuve, which was finally staged in Montreal on 14 March 1921 under the auspices of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, thanks to its president, Victor Morin. Because of the indifferent reception it received, it was not put on again, and it would not be published until 1974, in Montreal. In 1886 Laure Conan published at Quebec Si les Canadiennes le voulaient!, a dramatic work that had never been performed. Her plays, in which descriptions and interior monologues steal the spotlight from the dialogue, do not have the solidity of her so-called psychological novels.

In the winter of 1923 Félicité Angers was preparing an historical novel to enter in competition for the Prix David. She would finish writing it at the Villa Notre-Dame des Bois, run by the Religious of Jesus and Mary in Sillery, where she had been living since September 1923. On 10 March 1924 she sought advice from Lionel Groulx*: “I am working on my novel. . . . For the title, I am wavering between Au tournant tragique, Au sombre tournant and Sur l’épave, 1760.” On 18 May she asked Chapais to send for Mgr Eugène Lapointe* to hear her confession. Although she was in pain, she completed her novel on 20 May at eleven o’clock in the morning. The deadline had passed, yet she believed it might still be accepted by the jury. Six days later, Dr Roland Desmeules, her grandnephew, diagnosed her condition as ovarian cancer. She was operated on by Dr Arthur Simard*, but died of heart failure on 6 June at the Hôtel-Dieu at Quebec. She bequeathed almost all her possessions and royalties to Mgr Ovide Charlebois*, a missionary whose courage she had always admired. Her last novel, which was finally given the title La sève immortelle, would be published in Montreal in 1925 by Chapais, the executor of her will. Félicité Angers was buried in La Malbaie, in a plot next to that of Pierre-Alexis Tremblay. In 1924, in La Voix de Jésus-Marie, her unidentified biographer from Sillery would sum up her life in these words: “She served three great loves: her God, her country, and her pen.”

[The author would like to thank Sister Éliane Angers, of the convent of the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood in Trois-Rivières, Qué., for her recollections.

The following archives hold documents by or about Félicité Angers: ANQ-M, P82/109–1574; P133; ANQ-Q, CE304-S3, 10 janv. 1845; P406; ANQ-SLSJ, P2, docs.725A–Q; dossier 35.27; Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Archevêché de Montréal, 901.174 (Mgr Bruchési, corr. avec auteurs), .2.4 (Laure Conan); 990.070 (Élie Auclair, corr. avec auteurs), .2.6 (Laure Conan); RLBR (reg. des lettres de Mgr Bruchési), 5: 381–82. Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Évêché de Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., Reg. des lettres des évêques; Arch. de la Compagnie de Jésus, Prov. du Canada Français (Saint-Jérôme, Qué.), BO-165 (Émile Benoist), 3; Arch. de l’Univ. de Montréal, P56 (fonds Victor-Morin); Arch. de l’Univ. Laval, P225 (fonds Thomas-Chapais); Arch. des Religieuses de Jésus-Marie (Sillery, Qué.); Arch. des Religieuses Hospitalières de Saint-Joseph (Montréal); Arch. des Sœurs Adoratrices du Précieux-Sang (Saint-Hyacinthe), Chemise V.E.2 (Angers, Félicité, ou Laure Conan), 1879–85, 1895–1918, sans date. Arch. du Monastère des Ursulines (Québec); Arch. du Monastère des Ursulines (Trois-Rivières), III-C-2.13-277 (fonds sœur Marguerite-Marie [Eugénie Lasalle]); Arch. du Séminaire de Nicolet, Qué., F003 (L.-É. Bois); Arch. du Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe, AFG1 (fonds C.-P. Choquette); AFG2 (fonds Émile Chartier); AFG13 (fonds Rémi Ouellette); AFG34 (fonds F.-X. Solis); Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec (Montréal), mss 231 (fonds L.-H. Fréchette); Centre de Recherche Lionel-Groulx (Outremont, Qué.), P1 (fonds Lionel Groulx), A, 845; LAC, MG 26, G; MG 29, D27, D40; MG 30, D56; LMS-0009; MCQ-DSQ, P8, P9, P14, P32, P40; MCQ-FSQ, SME 9/44/62, 66, 105, 116, 165; SME 9/165/86; Musée de Charlevoix (La Malbaie, Qué.), P1 (fonds Roland Gagné); P4 (fonds Famille Desmeules); P10 (fonds Laure Conan); Univ. of Ottawa, Morisset Library, Rare Books, Laure Conan, L’oublié (Montreal, 1900), in which two letters from Laure Conan to Henri d’Arles [Henri Beaudé] are enclosed; VM-DGDA, BM2, S10, D11.

No exhaustive bibliography for the life and works of Félicité Angers has been published. The author has drawn up a list that includes Angers’s writings for periodicals, all the editions of her books, and reviews of her work, as well as articles in newspapers and magazines, theses, dissertations, chapters of books, and monographs written about her. A copy of this list, which completes and in some cases corrects the works mentioned below, is available at the DCB. m.b.]

Le Devoir, 7 juin 1924. Nicole Bourbonnais, “Angéline de Montbrun: à la jonction du vécu et du littéraire,” in L’aventure des lettres pour Roger Le Moine, Michel Gaulin et P.-L. Vaillancourt, édit. (Orléans, Ont., 1999), 63–77. Laure Conan [Félicité Angers], J’ai tant de sujets de désespoir: correspondance, 1878–1924, J.-N. Dion, édit. (Montréal, 2002); Œuvres romanesques, Roger Le Moine, édit. (3v., Montréal, 1974–75). Renée Des Ormes [Léonide Ferland], “Glanures dans les papiers pâlis de Laure Conan,” La Rev. de l’univ. Laval (Québec), 9 (1954–55): 120–35; “Laure Conan: un bouquet de souvenirs,” La Rev. de l’univ. Laval, 6 (1951–52): 383–91. René Dionne et Pierre Cantin, Bibliographie de la critique de la littérature québécoise et canadienne-française dans les revues canadiennes (1760–1899) (Ottawa, 1992). DOLQ, vols.1–2. Micheline Dumont, “Laure Conan,” Académie Canadienne-Française, Cahiers (Montréal), 7 (1963): 61–72. D. M. Hayne et Marcel Tirol, Bibliographie critique du roman canadien-français, 1837–1900 ([Québec et Toronto], 1968). Annette Hayward, “Les religieuses ratées du roman québécois avant 1960,” in La vieille fille: lectures d’un personnage, Lucie Joubert et Annette Hayward, édit. (Montréal, 2000), 51–82. Sœur Jean de l’Immaculée [Suzanne Blais], “Angéline de Montbrun,” Arch. des lettres canadiennes (Montréal et Paris), 3 (1964): 105–22; “Angéline de Montbrun: étude littéraire et psychologique” (mémoire de ma, univ. d’Ottawa, 1962). Maurice Lemire, “Félicité Angers sous l’éclairage de sa correspondance,” Voix et images (Montréal), 26 (2000–1): 128–44. Roger Le Moine, “Laure Conan et Pierre-Alexis Tremblay,” Rev. de l’univ. d’Ottawa, 36 (1966): 258–71. P. de Lokieldo, “Laure Conan à N.-D. des Bois,” La Voix de Jésus-Marie (Sillery), 4 (1924), no.4: 4. Gabrielle Poulin, “Angéline de Montbrun ou les abîmes de la critique,” Rev. d’hist. littéraire du Québec et du Canada français (Montréal), no.5 (hiver–printemps 1983): 125–32. Louise Simard, Laure Conan: la romancière aux rubans (Montréal, 1995).

Cite This Article

Manon Brunet, “ANGERS, FÉLICITÉ (baptized Marie-Louise-Félicité), known as Laure Conan,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/angers_felicite_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/angers_felicite_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Manon Brunet |

| Title of Article: | ANGERS, FÉLICITÉ (baptized Marie-Louise-Félicité), known as Laure Conan |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |