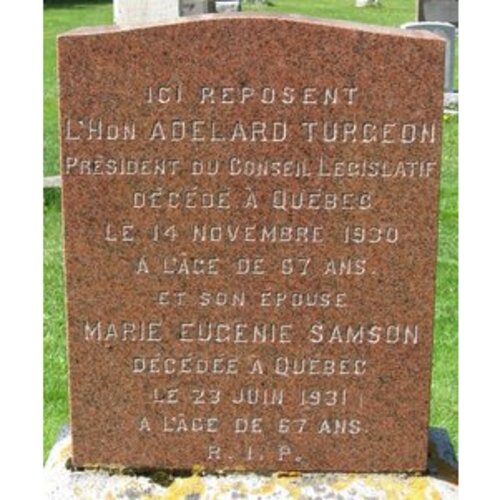

TURGEON, ADÉLARD, lawyer, politician, businessman, and philanthropist; b. 18 Dec. 1863 in Saint-Étienne-de-Beaumont (Beaumont), Lower Canada, son of Damase Turgeon, a sailor, and Christine Turgeon; m. 19 July 1887 Marie-Eugénie Samson in Lévis, Que.; they had no children; d. 14 Nov. 1930 at Quebec and was buried on 17 November in Saint-Étienne-de-Beaumont.

Adélard Turgeon, who was of Norman ancestry, came from a modest background. He attended the Collège de Lévis from 1874 to 1884 and following graduation entered the Université Laval at Quebec. While studying, he articled in the law firm of Isidore-Noël Belleau, Lawrence Stafford, and Eusèbe Belleau. After obtaining his llb and being called to the bar of the province of Quebec in 1887, he began his career in Lévis with Charles-Albert Lemay. The partners moved to Quebec in 1889, but he left Lemay that year. Turgeon, who would carry on his practice at Quebec until 1917, had other partners over the years: Henry George Carroll* from 1890 to 1897, Arthur Lachance from 1898 to 1906, Ernest Roy (who would also act as his secretary) from 1899 to 1901 and from 1906 to 1917, Auguste Tessier from 1902 to 1903, Michael Joseph Ahern from 1903 to 1906, Roméo Langlais from 1906 to 1917, Oscar-Jules Morin from 1910 to 1916, and François-Xavier Godbout from 1916 to 1917. Turgeon quickly became an important figure in Quebec legal circles and he was made a kc on 26 Aug. 1903.

Like many novice lawyers of his time who had political ambitions, Turgeon took up journalism. Along with 150 young Liberals, in 1888 he founded L’Union libérale, a feisty Quebec weekly that provided them with a training ground for future struggles. The paper, which called for a return to the great principles of liberalism, would cease publication in 1896. Under the pseudonym of Donoso, Turgeon contributed a number of articles to it between 1888 and 1890. He would also be listed as one of the five directors of Le Soleil in January 1897, shortly after this newspaper was founded.

Turgeon ran for the Liberals in Bellechasse, the stronghold of Conservative Narcisse-Henri-Édouard Faucher* de Saint-Maurice, in the provincial election of 17 June 1890. He was successful, and he retained his seat in 1892, although the Liberal party lost this election. Like François-Gilbert Miville Dechêne and Jules Tessier, he was among those who stoutly defended the integrity of Premier Honoré Mercier* at a time when it required some courage to do so. Following the Baie des Chaleurs Railway scandal, in which Mercier’s government was accused of bribery, the premier was fiercely attacked by the Conservatives, whose powerful political machine he had to face virtually alone. Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers*, a former Conservative minister, dismissed him from office on 16 Dec. 1891. Following the general election of 8 March 1892 which came at the end of an aggressive defamatory campaign, Mercier, now ill, abandoned, and ruined, found himself in opposition with 18 mlas, including Turgeon. The debates at that time contained particularly acrimonious attacks on Mercier, who was even taken to court. During his years on the opposition benches, Turgeon rose a number of times to defend him and his government. The general election of 11 May 1897 returned the Liberals to power under Félix-Gabriel Marchand*. Re-elected, Turgeon was named to the cabinet because of his prominence in the Quebec region and the fighting spirit he had shown while in opposition. He was made commissioner of colonization and mines. Returned by acclamation in 1900, he was offered the same post in Simon-Napoléon Parent*’s cabinet that year. Turgeon refused at first, but then accepted the office, which he would retain until 1901, when he was appointed secretary and registrar; in 1902 he became minister of agriculture. He was again elected by acclamation in 1904. In the Legislative Assembly in the period 1897–1904, he passionately championed the creation of a department of public instruction, and had to face frequent accusations that he was selling public resources to the Americans for a song. Forgoing this revenue (more than $15 million in 1901, according to the census), he told the assembly in 1904, would necessitate direct taxation to finance education, agriculture, and colonization.

The minister seemed headed for a brilliant career. On 27 March 1904 Olivar Asselin*, who knew Turgeon and his colleagues, wrote in the Montreal newspaper Le Nationaliste that “Mr Turgeon is virtually the head of the ministry. He has talent [and] ambition. We will judge him by his work.” But Turgeon was actively involved in the revolt against Parent and he resigned on 3 Feb. 1905, along with Lomer Gouin, whom he had known at school, and William Alexander Weir. His move was motivated by his sense of personal dignity and, given the discredit into which the Parent government had fallen, by the public interest. He was convinced that Parent had hatched a plot to humiliate them and force them to withdraw. A number of people thought that Turgeon might become premier, amongst them Senator Philippe-Auguste Choquette* (who reportedly supported his appointment) and parliamentarian Godfroy Langlois (who, by contrast, did not look kindly on this possibility). Turgeon was, however, too fond of his peace of mind, his comforts, and his travels, and he was not eager to assume too onerous responsibilities. It was Gouin who took over the office, with Turgeon’s support. In 1905 the new premier appointed Turgeon minister of lands, mines, and fisheries and then minister of lands and forests, a position he would retain until 1909.

Turgeon’s talents – his eloquence, his breadth of knowledge, his business and administrative sense – were recognized in Ottawa. In 1906 Sir Wilfrid Laurier* offered him a seat in the Senate and Charles Fitzpatrick*’s post as minister of justice and attorney general; he would also be put in charge of the Liberal forces in the Quebec region, which meant, among other things, responsibility for organization and political appointments. Because of Laurier’s friendly attitude towards Parent’s supporters, Turgeon refused this flattering offer and remained at Quebec to administer the province’s public lands. In this capacity, his principal tasks were to open new areas for colonization, create forest reserves, establish tighter control over logging, and fight forest fires more effectively.

At the height of Turgeon’s career, what became known as the Abitibi affair occurred. In 1905 the government, which was trying to attract French-speaking immigrants, wanted to establish a Belgian colony in the Abitibi region. The minister of lands and forests was sent as a delegate to the universal exposition held that year in Liège, to extol the province’s riches and attract investors. Some 15 financiers showed an interest. The influential Ferdinand-Dieudonné-Henri De L’Épine, Baron De L’Épine, acted as intermediary between a Belgian syndicate and Turgeon. According to the correspondence between De L’Épine’s wife and Mme Turgeon, the relationship between the two men took on “an intimate character” during Turgeon’s stay in Belgium. The baron filed an application to purchase 200,000 acres of land. The government gave him an option to buy at 70 cents an acre. In the course of discussions there was, however, talk of an additional sum of 30 cents an acre for the election fund. The money was to be paid to the intermediary, who would turn it over to the appropriate party. The negotiations led to an exchange of letters; one of these, from the baron to Turgeon, marked “confidential” and dated 28 Jan. 1906, proved disastrous for the minister, since it confirmed that a contribution had been solicited. Turgeon would assert that he had not received this letter, but rather another one, which did not contain the reference to the election fund. Though he was unable to provide the original, he would maintain that the letter brandished by Baron De L’Épine was a forgery, written after the fact for the purpose of ruining him – which may have been the case.

The affair came to light in 1907 during a libel suit brought against Olivar Asselin by Jean Prévost*, who had recently offered Gouin his resignation as minister of colonization, mines, and fisheries. Asselin was just waiting for this opportunity to expose the Abitibi scandal. Defence counsel Napoléon-Kemner Laflamme, who was advised by Armand La Vergne* and Charles-Alleyn Taschereau, succeeded in grilling Turgeon (who had been called as a witness because the famous letter was addressed to him), but in the end he did not uncover any misappropriation of funds, only instances of negligence and imprudence, and a few suspicions about the Liberal government. Le Nationaliste, which had extensively reported on the trial, would not let the matter drop. For weeks, under the byline of Pierre Beaudry (a pseudonym used by Jules Fournier*), it accused Turgeon of perjury. Exasperated, Turgeon sued the newspaper, and this second trial ended with a conviction on 16 Oct. 1907.

Exonerated by the courts, but weary of all the attacks, Turgeon demanded a commission of inquiry. He immediately resigned his seat as mla for Bellechasse, in order to submit his case to his true judges, the electors, and he pushed Henri Bourassa*, the leader of the Nationalistes, into a trap by challenging him to run against him. How could Bourassa, who had never set foot in this rural constituency, win against one of its own, who knew its every nook and cranny? Bourassa resigned his seat as mp for Labelle and took up the gauntlet. It was a memorable campaign. All the political powers criss-crossed the riding and Turgeon defended himself brilliantly. The municipal council of Saint-Étienne-de-Beaumont supported him. At Gouin’s request, Laurier expressed confidence in him.

On 4 November the voters made their choice. Turgeon was re-elected by a majority of 749 votes. Gouin set up the royal commission Turgeon had asked for when he resigned, naming judges François Langelier* and Napoléon Charbonneau to head it. Turgeon, who was called before it, testified that “never, at any time, was there any discussion between the Belgian syndicate, or any of its members, and myself of a contribution that was to be paid into the election campaign fund.” Given too narrow a mandate, the commission did not manage to shed any light on the matter. The evidence, which on the whole gives the impression that it was the baron who had lied, remains incomplete.

Turgeon and his party were returned in the general election of 8 June 1908. In a dramatic move, he resigned again. His resignation made it appear that he was running away, since he left the Legislative Assembly one month before Bourassa and La Vergne took their seats there. Many people saw this act as an evasion. On 16 June 1925 L’Événement would give health problems as his reason for moving to the Legislative Council, with its calmer atmosphere. Circumstances having changed greatly since 1906, he would gladly have gone to the Senate, to a position of prestige, that, moreover, was in Ottawa, where he could more easily have disappeared from public view. Although Gouin wanted to keep Turgeon in Quebec, he nevertheless contacted Laurier on his behalf, but to no avail. This “tall, handsome figure,” he wrote on 3 Aug. 1908, would do honour to Quebec. Two days later Laurier replied that he did not understand why Turgeon wanted to “fade into the background,” when, as a minister, he was “in the thick of the fray.” The upshot was that Turgeon had to be satisfied with the provincial upper house, where he took his seat on 2 Feb. 1909 at the age of 45. He represented the division of La Vallière and acted as speaker for the remaining 21 years of his life, the longest term ever served in this office.

Turgeon’s years in the upper house were happy ones. An art collector who enjoyed reading, receptions, good wine, golf, hunting, and business, the easy-going former minister lived the life of a dilettante. He travelled a good deal in Canada, France, Belgium, and New England. His oratorical skills, his charm, his “aristocratic distinction and his urbanity,” as Le Soleil would note on 14 Nov. 1930, met with success wherever he went. Turgeon cut a figure as a great lord and, thanks to his annual salary of $5,000 (in 1930) and the money his property is thought to have brought him, he became a philanthropist. For example, he gave $1,000 to the Collège de Lévis and contributed to the fund for erecting historical monuments to Samuel de Champlain* and Octave Crémazie*, among others. When Hector Fabre* died in 1910, Turgeon’s name was put forward for the post of Canadian high commissioner in Paris, but Philippe Roy, a senator from Alberta, was chosen instead. It is believed that in 1911 he wanted to succeed Sir Charles-Alphonse-Pantaléon Pelletier* as lieutenant governor of Quebec, but Parent, who was still influential, opposed the appointment. In 1917 he was rumoured to be moving to federal politics.

Along with his political life, Turgeon was involved in various organizations. In 1907, after strong opposition stemming from rivalry, during this period, between Liberals and Nationalistes, he was elected president of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Quebec City. He was named to the executive of the Quebec Technical School in 1916. In 1922 he became president of the Conseil Supérieur des Beaux-Arts and founding president of the Commission des Monuments Historiques de la Province de Québec. He was also a member of the National Battlefields Commission. Many honorary titles were awarded him: officer of the Order of Leopold in 1904, knight of the Legion of Honour in 1904 and officer in 1928, companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1906, and commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 1908. On 24 June 1901 France made him an officier de l’instruction Publique.

Turgeon also sat on numerous boards of directors. He was president of the Laurentian Water and Power Company, the Frontenac Realty Company, the Nor-Mount Realty Company Limited, and the Quebec Land Company (in which he was active in the division and sale of lots in Limoilou). He was vice-president of Provincial Securities Limited from 1918 to 1926 and of the Quebec Cartage and Transfer Company Limited, and a director of the Quebec Power Company. In 1900 he had been vice-president of the Quebec and Lake Huron Railway Company and he afterwards became a director and shareholder of the Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Saint-Laurent et Mégantic and the Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Montréal et Baie James, founded in 1902 and 1903 respectively. He had played a key role in the creation of the Quebec and Lake St John Railway [see Horace Jansen Beemer*] and he had been instrumental in founding the village of Honfleur (Sainte-Monique) in the Lac Saint-Jean region in 1898. At the beginning of the century, Turgeon put all his political weight behind Alphonse Desjardins* when the caisses populaires were being established. The federal government appointed him to a consultative committee to study the proposed St Lawrence canal system, and in 1927 he endorsed the minority report of fellow committee member Beaudry Leman, who recommended that the development of hydroelectric power be put in the hands of the state rather than of private enterprise. In so doing, as Télesphore-Damien Bouchard would state in the Legislative Assembly in 1935, Turgeon became one of the first defenders of at least partial nationalization of the province’s hydroelectric resources.

Turgeon died in office at Quebec on 14 Nov. 1930 at the age of 66 years and 11 months, following a long illness, probably of a pulmonary and respiratory nature. He had often been praised for his ability as speaker, which had been evident from his student days. His eloquence took its inspiration from French politicians and it was often compared to that of Laurier. He was tall, slender, naturally elegant, and haughty in bearing, with wavy hair that was thinning somewhat at the front. He was also a man of culture who enjoyed reading, especially history.

Given the offices he held, Adélard Turgeon played an important role in the political life of his time, but he could have gone further by becoming premier of Quebec or an influential minister in Ottawa. His carelessness and lack of willpower, the laxity of the Liberal government, circumstances, and the political practices of his day made him the whipping boy of the Nationalistes and Conservatives and marred a career that might have been even more brilliant. This highly talented son of Bellechasse in the end was a second-rank political figure, behind Wilfrid Laurier, Henri Bourassa, Lomer Gouin, and Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*.

Adélard Turgeon gave many speeches, several of which were published: Discours de l’hon. M. Lomer Gouin, premier ministre et de l’hon. M. Adélard Turgeon, ministre des Terres et Forêts, à Longueuil le 22 septembre 1907 (Québec, [1907?]); Discours prononcé par l’hon. M. Turgeon, ministre des Terres et Forêts, à St-Michel de Bellechasse, le 18 août 1907 ([Québec, 1907?]); The National Battlefields Commission: Hon. A. Turgeon in the Quebec Legislative Council reviews and explains the progress made in the work: monument to King Edward VII (Quebec, 1911); Provincial politics: speeches of Hon. A. Turgeon, minister of Lands and Forests, delivered at St. Michel of Bellechasse and Longueuil, in August and September, 1907 ([Québec?, 1908?]); The Roberts case: the judicial and social point of view: speech delivered in the Legislative Council on Wednesday, 22nd November 1922 ([Quebec, 1922?]).

ANQ-Q, CE301-S4, 19 déc. 1863; S100, 19 juill. 1887; P412; P433; P1000, D2348. Arch. de l’Assemblée Nationale (Québec), Commission royale re Abittibi, copie de la preuve, 1907–8; Procès-verbaux des séances, 1908. Arch. du Collège de Lévis, Qué., Corr. entre Wilfrid Laurier et Adélard Turgeon; Fichier des étudiants. Barreau du Québec (Montréal), Tableau de l’ordre des avocats, 1900–1. Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée Nationale (Québec), Service de la recherche, dossiers des parlementaires; Service de la reconstitution des débats, Débats, 1930–31 (texte manuscrit). Cimetière de la Paroisse Saint-Étienne (Beaumont, Qué.), Pierre tombale d’Adélard Turgeon. NA, MG 26, G (mfm. at ANQ-Q). Le Devoir, 14 nov. 1930. L’Événement, 20 août, 10 sept., 6–7 juin, 29 oct. 1907. Le Nationaliste (Montréal), 27 mars 1904; 9–10, 16, 30 juin, 7, 14, 21, 28 juill., 27 août, 22, 29 sept., 20, 27 oct., 3, 10, 17 nov., 15 déc. 1907; 18 mai 1908; 17 janv., 21 nov. 1909. La Patrie, 15 juill.–5 nov. 1907. Le Soleil, 27 nov. 1897; 4 oct. 1902; 23 nov., 21 déc. 1904; 17 mai, 26 août 1905; 30 juin 1906; 25 juin, 10 sept., 18, 24, 28 oct., 5 nov. 1907; 24 juill. 1908; 5 févr. 1914; 8 juill. 1916; 8, 28 juin 1922; 7 avril 1928; 14 nov. 1930. Georges Bellerive, Orateurs canadiens-français aux États-Unis; conférences et discours (Québec, 1908). C.-M. Boissonnault, Histoire politique de la province de Québec (1867–1920) (Québec, 1936). Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), vol.2. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). P.-A. Choquette, Un demi-siècle de vie politique (Montréal, 1936). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. Dîner offert à l’honorable Adélard Turgeon par ses amis de Lévis à l’occasion de son départ pour Québec au Club de la garnison, jeudi, le 26 septembre 1901 (Lévis, 1901). Directories, Quebec, 1880–91, 1916–21; Quebec and Levis, 1889–1916. BCF. DPQ. P. A. Dutil, “The politics of progressivism in Quebec: the Gouin ‘coup’ revisited,” CHR, 69 (1988): 441–65. Encyclopaedia of Canadian biography . . . (3v., Montreal and Toronto, 1904–7), vol.1. J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vols.2–3. Hector Laferté, Derrière le trône: mémoires d’un parlementaire québécois, 1936–1958, Gaston Deschênes, édit. (Sillery, Qué., 1998). Charles Langelier, Souvenirs politiques; récits, études et portraits (2v., Québec, 1909–12). “Le Nationaliste” devant la justice de son pays, condamné au maximum de la pénalité; remarques indignées et émues du juge: il regrette de ne pouvoir prononcer une sentence d’emprisonnement (Québec, [1907?]). 1905, the settler’s guide: province of Quebec (Quebec, 1905). Hélène Pelletier-Baillargeon, Olivar Asselin et son temps (2v. paru, [Montréal], 1996– ). Prominent men of Canada: a collection of persons distinguished in professional and political life, and in the commerce and industry of Canada, ed. G. M. Adam (Toronto, 1892). Qué., Assemblée Législative, Débats, 1890, 1892–1909. A.-B. Routhier, Québec et Lévis à l’aurore du XXe siècle (Montréal, 1900). P.-G. Roy, À travers l’histoire de Beaumont (Lévis, 1943); Les avocats de la région de Québec (Lévis, 1936 [i.e. 1937]). Robert Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec; Honoré Mercier et son temps (2v., Montréal, 1975). Gustave Turcotte, Le Conseil législatif de Québec, 1774–1933 (Beauceville, Qué., 1933). Univ. Laval, Annuaire, 1885–88. Un ministre canadien à Mortagne: réception de l’honorable Turgeon, ministre des Terres et Forêts de la province de Québec, par la Société percheronne d’histoire et d’archéologie; Discours de M. Charles Turgeon, professeur à la faculté de droit de l’université de Rennes (Bellême, France, 1905). J. S. Willison, Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberal party: a political history (2v., Toronto, 1903), 2: 34–35.

Cite This Article

Jocelyn Saint-Pierre, “TURGEON, ADÉLARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/turgeon_adelard_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/turgeon_adelard_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jocelyn Saint-Pierre |

| Title of Article: | TURGEON, ADÉLARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |

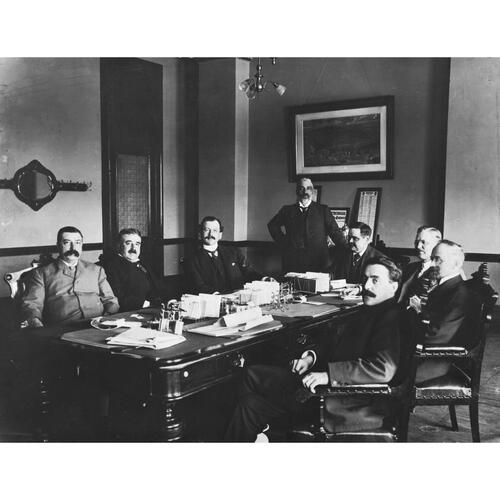

![L'honorable Adélard Turgeon, secrétaire provincial à Québec [image fixe] Original title: L'honorable Adélard Turgeon, secrétaire provincial à Québec [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.3255.jpg)