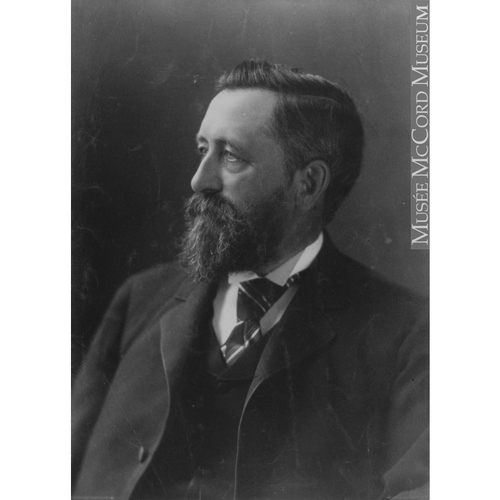

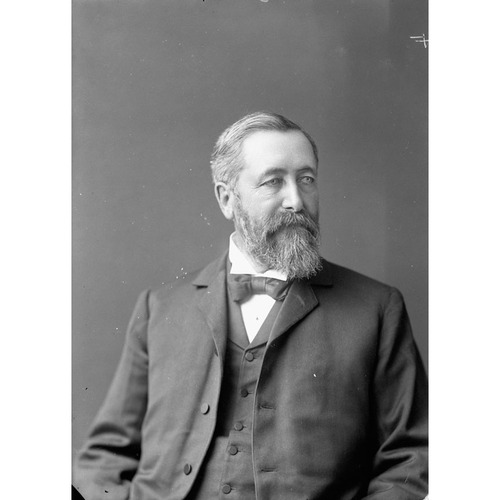

SAUNDERS, WILLIAM, pharmacist, scientist, civil servant, and author; b. 16 June 1836 in Crediton, England, son of James Saunders, a shoemaker and Methodist lay preacher, and Jane Wollacott; m. 1 Aug. 1857 Sarah Agnes Robinson, daughter of the Reverend Joseph Hiram Robinson*, and they had a daughter and five sons; d. 13 Sept. 1914 in London, Ont.

William Saunders came to Canada with his parents in 1848 and joined his brother Stephen, who had earlier settled at London. It is likely that he was privately educated as a child. At the age of 19 he was apprenticed to John Salter, a local druggist. Later in 1855 he opened his own pharmacy, which he subsequently expanded into a pharmaceutical business that sold medicinal extracts made from plants. His interest in plant diseases led him to study entomology and to begin scientific writing. Saunders was a practical botanist and agriculturalist whose interests initially tended more to the collection of samples for such naturalists as William Hincks* and David Allan Poe Watt than to theory. In 1862 he and Charles James Stewart Bethune* took steps that led the following year to the formation of the Entomological Society of Canada. A founding member in 1867 of the Canadian Pharmaceutical Society and later its president, in 1871 he helped establish the Ontario College of Pharmacy [see William Elliot*]. Six years later he became president of the American Pharmaceutical Association.

In 1869 Saunders bought a farm east of London, planted fruit-trees, and began the experiments in hybridization that he described in the publications of the Fruit Growers’ Association of Ontario, in which he was also involved. His business interests expanded in 1876 when he was made a director of the Huron and Erie Savings and Loan Company; he was its president between 1879 and 1887. These activities might have taxed many, but Saunders also found time to prepare entomological exhibits for the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 and a fruit display for the exhibition held in London, England, in 1886, to teach materia medica in the medical school of the Western University of London, Ontario, in the 1880s, to give papers to the American Forestry Congress, to serve as a public analyst and consultant to the province on agriculture and entomology, and to participate with his family in a host of musical activities. Saunders’s presidency of both the Entomological Society (1875–86) and the Fruit Growers’ Association (1882–86), his editorship of the Canadian Entomologist (1873–86), and his groundbreaking Insects injurious to fruits (Philadelphia, 1883) all served to confirm his renown as an entomologist and horticulturist. A charter-member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1882, he was its president in 1906–7.

Saunders was well known to fellow Londoner and Conservative John Carling, provincial commissioner of agriculture and public works in 1867–71 and federal minister of agriculture from 1885 to 1892. As early as 1871 Carling had enlisted Saunders’s aid to investigate a serious infestation of Colorado potato beetles in western Ontario. Carling, who must have been aware of Saunders’s membership in the Ontario agricultural commission of 1880–81, believed that science could improve Canadian agriculture and speed the development of the northwest. When he set up the Dominion Experimental Farms system in 1886, based on a study done by Saunders, the London pharmacist was made its director.

Turning over his pharmaceutical business to his sons William Edwin and Henry Scholey, Saunders moved to Ottawa in 1887. By this time he was over 50, but he brought to his position the same ability, energy, and vision that he had displayed in his youth. Five experimental farms were soon established: a central farm at Ottawa and regional farms at Nappan, N.S., Brandon, Man., Indian Head (Sask.), and Agassiz, B.C. Later, under Liberal minister of agriculture Sydney Arthur Fisher*, seven more experimental stations were set up, in locations ranging from northern Alberta to Prince Edward Island. Travelling in all seasons, by train, wagon, sleigh, and horse, Saunders personally chose most of these sites, although political considerations inevitably played a part in the selection process, particularly during Fisher’s regime.

The experimental farms, unquestionably Saunders’s most important work, conducted research in cereal culture, dairying, animal husbandry, horticulture, forestry, and the application of chemistry and botany to agriculture. Saunders and his political masters expected this research to produce practical results in the form of better varieties of grain, improved livestock, and fruit-trees that could thrive in the Canadian climate. They were not disappointed, but James Fletcher*, Charles Gordon Hewitt, and other scientists hired by Saunders often preferred to emphasize fundamental research. The conflict generated by these two concepts of the farms’ function occasionally strained Saunders’s relations with his subordinates. Politicians promoting pet projects, such as raising yaks at Brandon, also troubled him, though his own unsuccessful attempt in 1901 to plant trees on windswept Sable Island, N.S., indicates that he too could get carried away. In spite of such distractions, Saunders turned the experimental farms into a rich source of seeds and cuttings, published information, and innovation in agriculture. He developed many hardy varieties of fruit-trees, including crab-apple trees, and experimented through cross-fertilization and hybridization to find improved types of grain for prairie farmers. In 1903 he hired his son Charles Edward*, and his faith in his ability was justified when Charles, carrying on work begun by his father, developed the early maturing Marquis wheat, for decades the most important variety grown on the prairies.

William Saunders was given many honours by contemporaries, among them llds from Queen’s College in Kingston (1896) and the University of Toronto (1904) and a cmg in 1905. By 1910, however, the ageing Saunders was perceived by such younger scientists as Otto Julius Klotz* to be old-fashioned in his methods. His health failing, he retired in 1911. The Department of Agriculture sent him on a year-long tour of Europe as a gift, after which he returned to London, where he died in 1914. Two of his sons had distinguished careers of their own. Charles was knighted in 1934 for his work as dominion cerealist from 1903 and Frederick Albert became a prominent physicist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Although Saunders was one of the last of the self-taught natural scientists to rise to prominence in Canada, he was no amateur. He was a professional in the sense that he earned his living as a scientist. As an agriculturist, he made significant contributions to the settlement of the northwest and his work in establishing the experimental farms qualifies him as a pioneer of research and development in Canada.

Entries for several hundred articles published by William Saunders between 1861 and 1913 appear in Science and technology biblio. (Richardson and MacDonald), including numerous contributions to the American Pharmaceutical Assoc., Proc. of the annual meeting (Baltimore, Md, etc.); the Canadian Entomologist (London, Ont.); the Entomological Soc. of Ontario, Annual report (Toronto); the Canadian Horticulturist (St Catharines, Ont.; Toronto; etc.); and RSC, Trans. His official reports as director of the experimental farms appear in the branch’s reports for 1887–1911, in Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1888–1912. His publications also include Report of an inquiry in regard to the prevalence and ravages of the Colorado potato beetle . . . (Toronto, 1871), co-authored by Edmund Baynes Reed of the Entomological Soc. of Ontario, and the entry for “Dominion Experimental Farms” in Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 5: 79–85. A second edition of his monograph Insects injurious to fruits was published at Philadelphia in 1910.

Middlesex East Land Registry Office (London), Abstract index to deeds, London Township, concession C, lot 7 (mfm. at AO). NA, MG 29, B19; MG 30, B13, 3, book 24, 31 Oct. 1909; RG 17, A I, 781; 983; 1928: 53–62; 2745; 2747; 2755; 2766. PRO, RG 4, Mint Wesleyan Methodist Church, Exeter, Eng., RBMB, 17 July 1836 (mfm. in Devon and Cornwall Record Soc. Library, Exeter). Univ. of Western Ont. Library, Regional Coll. (London), William Saunders papers, including biog. summary. London Advertiser, 14 Sept. 1914. Can., Experimental farms service, Fifty years of progress on Dominion Experimental Farms, 1886–1936 (Ottawa, 1939). Canada, an encyclopædia, 5: 368. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Directory, London, 1856/57. Entomological Soc. of Ontario, Accounts and minutes of the London branch of the Entomological Society of Ontario, 1864–1881, ed. W. W. Judd (London, 1975); Minutes of the Entomological Society of Ontario while headquartered in London, Ontario, 1872–1906, ed. W. W. Judd (London, 1976). W. W. Judd, Early naturalists and natural history societies of London, Ontario (London, 1979). J. W. Morrison, “Marquis wheat – a triumph of scientific endeavor,” Agricultural Hist. (Urbana, Ill.), 34 (1960): 182–88. E. M. Pomeroy, William Saunders and his five sons: the story of the Marquis wheat family (Toronto, 1956). RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 9 (1915), proc.: viii-x.

Cite This Article

Ian M. Stewart, “SAUNDERS, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saunders_william_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saunders_william_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ian M. Stewart |

| Title of Article: | SAUNDERS, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 4, 2025 |