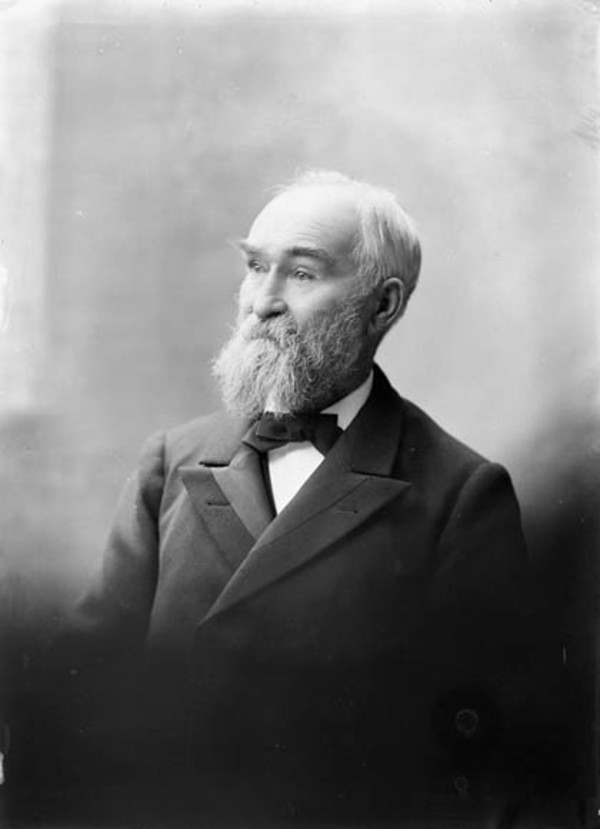

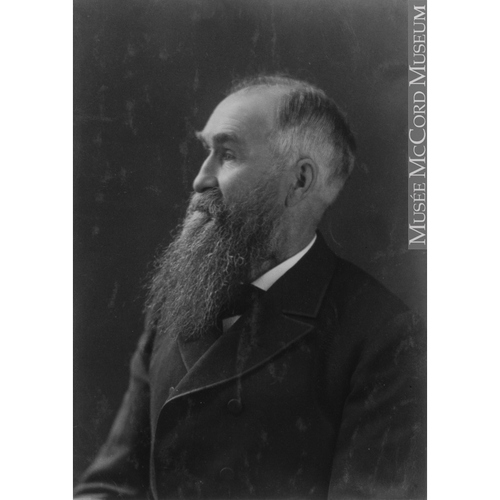

MACOUN, JOHN, teacher, botanist, naturalist, civil servant, and author; b. 17 April 1831 in the parish of Maralin, County Down (Northern Ireland), third of the four children of James Macoun, a soldier, and Anne Jane Nevin; m. 1 Jan. 1862 Ellen Terrill (d. 1921) of Brighton, Upper Canada, and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 18 July 1920 in Sidney, B.C.

John Macoun (pronounced Macown) was raised on family land that had been granted to one of his father’s ancestors almost two centuries earlier for military service. It was an ideal setting for a boy with an insatiable curiosity, and he developed a great passion for the outdoors and the natural world. Fatherless from the age of six, he became independent and exceedingly stubborn, almost self-righteous, in his determination to succeed. His education at the parochial school of the Presbyterian Church strengthened this faith in his capabilities. Macoun was a pompous young man who considered himself morally superior, because of his virtues, and seldom wrong. As well, he was prepared to fight for his beliefs, confident that he would prevail. By the time he had assumed a clerk’s position in Belfast, in his teens, he also held the same values as his fellow Ulstermen: allegiance to the crown, dedication to union with Britain, and support for the Conservative party and the Orange order.

In the spring of 1850 the Macoun family emigrated to Upper Canada, settling on a farm in Seymour Township near Anne Macoun’s brother. It was here, while working in the fields and forests, that John developed a serious interest in the local flora. Never satisfied as a farmer, he became a public-school teacher in 1856 and taught in small country schools in the district before securing a position in Belleville in 1860. Probably through his friendship with Mackenzie Bowell of the Belleville Intelligencer, Macoun became a supporter of the local Orange lodge and the Conservative party. In addition, he briefly served as a volunteer at Prescott during the Fenian troubles in 1866.

Macoun would look upon his move to Belleville as a turning-point in his career, for at that time he decided to devote every spare moment to botany and the development of a herbarium. His exhaustive fieldwork, study, and contacts with leading botanists in Canada and abroad, among them Sir William Jackson Hooker, Louis-Ovide Brunet*, and George Lawson*, established him as an expert on the flora of the region. He generally favoured field activity over difficult scientific analysis, which he often passed on to Hooker, American botanist Asa Gray, and others with formal training, and he would continue to do so even after assuming a new chair in natural history at Albert College in Belleville in 1868.

While on a collecting trip to the Owen Sound region in 1872, Macoun, or the Professor as he was popularly known, happened to meet Sandford Fleming, chief engineer of the Pacific railway, who invited him to take part in a survey of its projected route westwards. During five separate surveys of regional potential as well as railway routes, between 1872 and 1881, Macoun examined the agricultural capabilities of various western tracts and concluded, largely on the basis of natural vegetation, that all of the northwest, including the arid southern plains, was an agricultural Eden. This enthusiastic but unsubstantiated assessment dovetailed with the federal government’s expectations for the region and made Macoun a darling of the Conservative party. His evaluation was also used to justify the re-routing of the Canadian Pacific Railway across the southern prairies. Macoun would publish a full account of his western work in the extremely popular but propagandistic Manitoba and the great north-west . . . (Guelph, Ont., 1882).

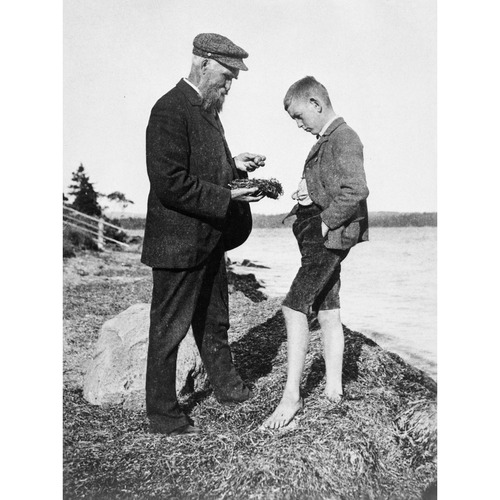

As early as 1874 Macoun’s reports had come to the attention of Alfred Richard Cecil Selwyn*, director of the Geological Survey of Canada, the scope of which was enlarged three years later to include natural history. In 1879, acting on the initiative of Mackenzie Bowell, then minister of customs, the government took the unprecedented step of hiring Macoun permanently as its explorer in the northwest. He was named dominion botanist to the GSC in November 1881 and the following year he moved with his family to Ottawa. In 1887 he was appointed the survey’s naturalist and one of its assistant directors. Macoun was to have a decisive influence on the kind of natural science pursued under the auspices of the GSC. Scorning Darwinism, he believed that a naturalist should be a jack of all fields, whose role was to assemble a complete and accurate inventory of what Macoun saw as God’s wondrous bounty. He consequently spent as much time as possible in the field each season, collecting not simply plants but all living things, often with the assistance of one of his two sons, James Melville and, to a lesser extent, William Terrill. As well, he started to produce a catalogue of Canadian plants in 1883 and then one on Canadian birds.

Macoun’s broad collecting activity mirrored the expansionist philosophy underlying the national development policies of the Conservative governments of Sir John A. Macdonald* and later of the Liberal governments of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. He saw it as his duty to provide practical information on the dominion’s natural life that could be used to further economic growth and promote national well-being. Thus, whenever he was sent to assess the potential of a particular region, he always returned brimming with optimism and frequently overstated the case. His enthusiasm knew no bounds, as evidenced by his testimony before various government committees. Macoun was convinced that the country, with its great resources, would become the home of a superior civilization where countless millions would experience a fresh start, as he had.

Not everyone was taken in by Macoun. In 1883 his superior, Lindsay Alexander Russell, deputy minister of the interior, called the temperamental naturalist “a good specialist and honest fool outside of that.” Western developer Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt*, GSC geologist George Mercer Dawson*, and retired explorer Henry Youle Hind*, who publicly challenged Macoun in 1883, knew of large areas of the northwest that in their estimate were unfit for agriculture, but it was Macoun’s contagious enthusiasm that most influenced policy. In reality, his unqualified championship, and the resulting belief that settlers required little assistance at the pioneering stage, would lead to much hardship, and thus undermine federal homestead policy.

During his 31 years with the GSC in Ottawa, the outspoken Macoun was a prominent figure in the city’s social and intellectual circles. He became a leader of the Ottawa Field-Naturalists’ Club – he was its president in 1886–87 – and gave entertaining lectures before the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society. His home at 98 James Street was often a popular gathering place for evening discussions. Through his association with some of the country’s leading scientists, he was named a charter-member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1882 and he was a regular visitor at the governor general’s residence.

Macoun’s feverish rounds of activity and travel came to an abrupt end in 1912, when he suffered a paralytic stroke and, with his ailing wife, moved to Sidney on Vancouver Island to live with their eldest daughter. Even then, however, he did not retire completely from the GSC. Right up until his death in 1920, he continued to submit reports and collect specimens along the coast, in addition to working on his autobiography. He was buried in Patricia Bay Cemetery and was reinterred in 1921, along with his wife, beside their son James at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa.

Macoun’s work in natural history, particularly for the GSC, had its costs and benefits. His annual summer field trips were little more than haphazard sweeps through a region to gather whatever was chanced upon. Because of his emphasis on making large collections, the specimens generally were poorly preserved and documented and field collections sometimes sat around for years before they were gone over. By concentrating on fieldwork, Macoun also had limited time to devote to detailed study and publication. He always believed that it was more practicable, given his broad field of enquiry, to concentrate on what he did best and leave it to others, in particular American scientists, to identify and name his difficult specimens. This obsession with collecting, with special emphasis on the discovery of unknown species, also meant that the GSC’s endeavours in natural history went in the opposite direction from those of similar institutions in Europe and the United States. Whereas many other natural scientists were increasingly concentrating on a particular field or genus, for example Rudolph Martin Anderson* (mammals), Matte Oscar Matte (botany), and Percy Algernon Taverner* (birds), Macoun’s duties, at his own request, were expanded to include all forms of natural life.

On a more positive note, without Macoun’s profound belief in himself and his work, it is unlikely that the GSC would have engaged in natural history to the extent that it did. Thanks largely to his activity, natural history came to be regarded as a legitimate concern of the survey. Macoun’s enormous collections also figured in the establishment in 1911 of the Victoria Memorial Museum (designated the National Museum of Canada in 1927). His greatest legacy, however, was his ability as a field naturalist. A tireless field man who could recognize new forms at sight and who discovered a large number of species and subspecies, many of which were named after him, he covered an incredible range of territory – from Atlantic Canada to the Pacific coast and as far north as the Yukon – making large collections in all kinds of environments. It is not too exaggerated to say that John Macoun tried almost single-handedly to roll back the natural-history frontiers of Canada.

John Macoun’s publications include Catalogue of Canadian plants . . . (7 pts. in 4v., Montreal, 1883–1902) and Catalogue of Canadian birds (3 pts., Ottawa, 1900–4, the latter co-authored by his son James Melville Macoun. The Autobiography of John Macoun, m.a. . . . was issued posthumously ([Ottawa], 1922) with an introduction by Ernest Thompson Seton*.

NA, MG 24, K28; RG 132, 1, vol.18–35. National Museum of Natural Sciences (Ottawa), Botany div., John and James Macoun, botanical field notebooks. National Museums of Canada Library (Ottawa), John and James Macoun letter-books. W. A. Waiser, The field naturalist: John Macoun, the Geological Survey, and natural science (Toronto, 1989); “A willing scapegoat: John Macoun and the route of the CPR,” Prairie Forum (Regina), 10 (1985): 65–81. Morris Zaslow, Reading the rocks: the story of the Geological Survey of Canada, 1842–1972 (Toronto and Ottawa, 1975).

Cite This Article

W. A. Waiser, “MACOUN, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macoun_john_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macoun_john_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. A. Waiser |

| Title of Article: | MACOUN, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 23, 2025 |