Source: Link

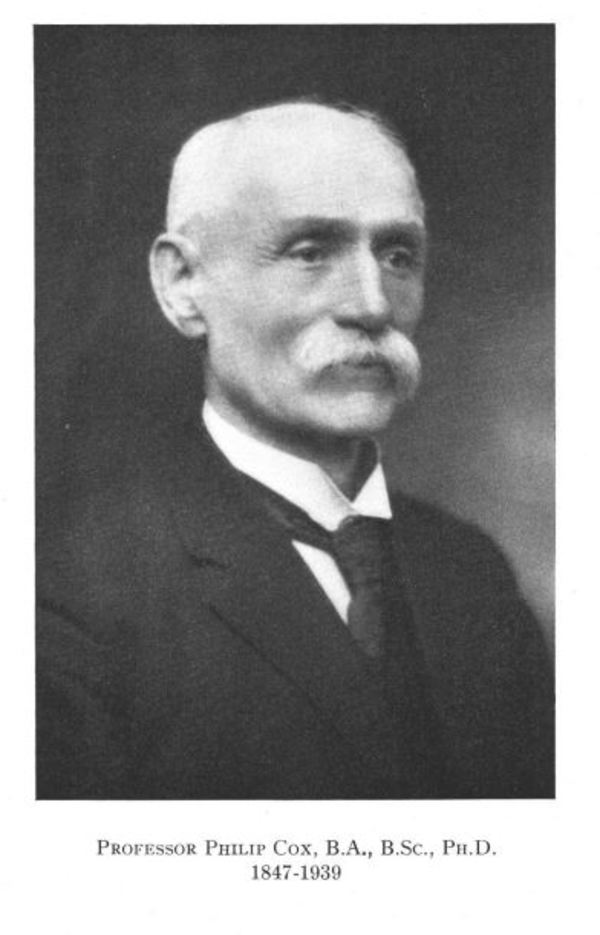

COX, PHILIP, educator, natural scientist, and author; b. 1 Sept. 1847 at Upper Maugerville, N.B., son of Philip Cox and Katherine (Catherine) Fleming; m. 12 Aug. 1903 Mary Jane Mowatt in Saint John, and they had two daughters and a son; d. 12 Sept. 1939 in St Andrews, N.B.

Philip Cox grew up on a farm in a large Irish Catholic family of limited means. He attended the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, which was unusual at the time for someone from this background. An honours student in mathematics and natural science, he took a ba in 1871 and entered the field of education. He was principal of the Queens County Grammar School at Gagetown (1871–77), an inspector of schools in northern New Brunswick (1879–84), principal of Harkins Academy and supervisor of schools at Newcastle (1885–92), and principal of the grammar school and supervisor of schools at Chatham (1897–1907). Between times he taught in Saint John, did postgraduate study at the university in Fredericton, and engaged in other activities.

In an 1885 report, inspector George William Mersereau described Cox, then at Newcastle, as an “able,” “earnest,” and “zealous” educator. As a forward-looking school inspector, Cox had been sincerely concerned for the welfare of pupils and teachers. This attitude was notable in his analysis of the difficulties faced by schools in the French-speaking areas of the province [see Valentin Landry*] when most of the authorized textbooks were written in English. While his fellow inspectors were silent on the subject, Cox pointed out in his report for 1883 and again in 1884 that, by failing to provide more books in French, the province was placing a heavy burden on francophone teachers and “closing the doors against the pupils acquiring an acquaintance with the idiomatic and classic beauty of their native tongue.” In 1893, speaking at a meeting of the Northumberland County Teachers’ Institute, he made an eloquent plea for a greater emphasis on science: “Our children must be led to examine the facts and laws of life and matter, and drink at the reservoir of eternal truth, wisdom and power, which, in the abstract, we call nature.” As a school principal and supervisor in Newcastle and Chatham, he strove to be a role model. Mersereau’s 1885 report on his performance at Harkins Academy states that every pupil is benefiting from his influence and that “the teachers under him are stimulated and encouraged by his example, no less than by his precept.” His relations with school authorities in Fredericton were less salutary, and in 1892, after he failed to win a lengthy dispute with the provincial Board of Education over which class of teaching licence he was entitled to hold, he resigned at Newcastle and took an instructional position at the Saint John Grammar School. A year later he abandoned that post as well and entered into a period of further study and part-time employment.

While pursuing his professional career, Cox expanded upon his university studies in natural science by reading, exploring, collecting, and cataloguing. He made his debut as a naturalist in 1887 with an article in Auk on “Rare birds of northeastern New Brunswick.” This was the first of three articles on birds that he contributed to this journal in the late 1880s. Later, he and the young American naturalist William Joseph Long took summer expeditions by canoe up the feeder streams of the Miramichi River, where he collected specimens of plants, animals, birds, and fishes. His scientific studies were recognized by the University of New Brunswick in 1890 with the award of a bsc degree, and more emphatically in 1894, when the university’s first phd in science was conferred on him.

In the 1890s Cox published seven papers in the Bulletin of the Natural History Society of New Brunswick, including a treatise on the “History and present state of the ichthyology of New Brunswick.” He was qualified for a college or university position, but none was available in New Brunswick. Instead, in January 1897, he accepted the principalship of the Chatham Grammar School, along with supervisory responsibility for the town’s other schools. Soon after he assumed his duties, he also organized a natural history club for adults. The Miramichi Natural History Association, of which he was recognized as a co-founder, was born of this initiative. Between 1899 and 1907 the Proceedings of the association carried eight more of his papers. As well, he played a key role in establishing the Miramichi Natural History Museum, and his donations constituted a sizeable proportion of the first exhibits.

Controversy swirled about Cox in the fall of 1900 when he shot a caribou without first purchasing a hunting licence. He said he had killed it for the use of the natural history association, but David George Smith, editor of the Miramichi Advance and an early conservationist, labelled him “a common poacher.” Smith’s relentless badgering about “L’affaire Caribou” provoked Cox to publish a long, sarcastic letter in the Chatham World, the aim of which was not so much to set the facts straight as to belittle his tormentor. It would be difficult not to agree with Smith’s characterization of it as “a lot of silly verbiage.” Cox was duly charged with violating the game laws, and although he acted “very high and mighty” at his trial, he was found guilty and required to pay a stiff fine.

Cox left Chatham in 1907, at almost 60, when the University of New Brunswick named him professor of natural history and geology, as successor to his former mentor, Loring Woart Bailey*. Professor Bailey had burned a bright light for science at the university for 46 years, and it was doubted that either of the two applicants for his position (the other being his son George Whitman Bailey, md) could do justice to his legacy. Those who supported Cox’s appointment included John Macoun* of the Geological Survey of Canada, who thought he should be given an opportunity to inspire others with “that zeal for natural history work” which had earned him “such a prominent place among Canadian Naturalists.”

During his 23 years at the university Cox taught ba and bsc candidates as well as students in the forestry and engineering programs. Early in his tenure, he found another outlet for his interests as a volunteer at the federal government’s Atlantic Biological Station in St Andrews, where he assisted with research and administration. He enthusiastically participated in the station’s investigative expeditions to the Îles de la Madeleine and elsewhere on the east coast, displaying a stamina that “put younger men to shame.” Ten papers on his scientific experiments appeared in Contributions to Canadian Biology and related publications, and he is credited by ethologist Miles H. A. Keenleyside with being one of the first Canadian scientists to report research findings on fish behaviour. From 1923 to 1935 he represented the university on the Biological Board of Canada.

Cox had a number of notable students, including William Austin Squires, who was curator of natural science for many years at the New Brunswick Museum and could be regarded as his intellectual successor. The best-known of his students, however, was William Maxwell Aitken*, later Lord Beaverbrook, whom he had taught at Harkins Academy in Newcastle. Cox and his wife took part in an overseas study tour for educators that Beaverbrook sponsored in the mid 1920s, and before Cox retired in 1930, Beaverbrook granted his former teacher a handsome lifetime annuity. Correspondence between the two men is found in the Beaverbrook Papers in the Parliamentary Archives of the British House of Lords, in which Cox writes to “Max” and Beaverbrook to “My Dear Master.” In one of his letters, Cox refers to their 40-year relationship as an example of “the lasting and sacred nature of early friendships,” and Beaverbrook confirmed its significance by visiting his old teacher shortly before his death at age 92.

Tangible reminders of Cox’s fruitful association with the university include a portrait commissioned by the class of 1927, which hangs in his former laboratory, and the Dr Philip Cox Memorial Prize for biology, which has been awarded annually since the 1940s. His contribution to scientific inquiry in the province is signified by Mount Cox, a peak in the Naturalists Mountains near Upsalquitch Lake in northern New Brunswick.

The author wishes to acknowledge the family information provided by Philip Cox’s granddaughter, Mary Oland, née Hachey, of Rothesay, N.B.

Lists of Cox’s donations to the Miramichi Natural Hist. Museum appear in issues of Miramichi Natural Hist. Assoc., Proc. (Chatham, N.B.), beginning with vol.1. No complete list of Cox’s publications has been compiled. The following are among his works: in Auk: a Quarterly Journal of Ornithology (New York): “Rare birds of northeastern New Brunswick,” 4 (1887): 205–13; with John Brittain, “Notes on the summer birds of the Restigouche valley, New Brunswick,” 6 (1889): 116–19; “A bird wave,” 6: 241–43; in N.B., Natural Hist. Soc., Bull. (Saint John): “Observations on the distribution and habits of some New Brunswick fishes,” 11 (1893): 33–42; “History and present state of the ichthyology of New Brunswick,” 13 (1895): 27–61; “Catalogue of the marine and fresh-water fishes of New Brunswick,” 13: 62–75; “Notes on the occurrence of two shrews new to New Brunswick,” 14 (1896): 53–54; “Report on zoology,” 14: 55; “Batrachia of New Brunswick,” 16 (1898): 64–66; in Miramichi Natural Hist. Assoc., Proc.: “The anoura of New Brunswick,” 1 (1899): 9–19; “Cyprinidæ of eastern Canada,” 2 (1901): 36–45; “The snakes of the Maritime provinces of Canada,” 3 (1903): 11–20; “Reduction in the number of fin-rays of certain flat-fishes,” 3: 42–47; “Life of Moses Henry Perley, writer and scientist,” 4 (1905): 33–40; “Extension of the list of New Brunswick fishes,” 4: 41–44; “The beaver in its relation to forestry,” 5 (1907): 23–29; “Lizards and salamanders of Canada,” 5: 46–55; in Contributions to Canadian Biology: Being Studies from the Biological Stations of Canada (Ottawa and [Toronto]): “Are migrating eels deterred by a range of lights – report on experimental tests,” 1916: 115–18; with Marian Anderson, “A study of the lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus L.),” new ser., 1 (1922–24), no.1: 1–20; “Larvæ of the halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.),” new ser., 1, no.21: 409–12. Cox also published articles in Canadian Forestry Journal (Ottawa), Canadian Record of Science (Montreal), Ottawa Naturalist, and RSC, Trans.

LAC, RG 31, C1, 1901, Chatham, D-5: 13. N.B. Museum (Saint John), W. F. Ganong fonds, scrapbook no.4. PANB, RS 113, 1/6; RS 141 B7, F 15905, no.1502 (mfm.); RS 141 C5, F 19354, no.23379 (mfm.). Parliamentary Arch., House of Lords Record Office (London), BBK (Beaverbrook papers). Daily Gleaner (Fredericton), 13 Sept. 1939. Miramichi Advance (Chatham), 14 Jan., 4 Feb. 1897; 18 Oct. 1900. Union Advocate (Newcastle, N.B.), 31 Aug. 1892, 12 Dec. 1900. World (Chatham), 13 Oct. 1900. Kenneth Johnstone, The aquatic explorers: a history of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada (Toronto, 1977). M. H. A. Keenleyside, “Development of research on fish behaviour as part of fisheries science in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences ([Ottawa]), 54 (1997): 2709–19. K. F. C. MacNaughton, The development of the theory and practice of education in New Brunswick, 1784–1900: a study in historical background, ed. A. G. Bailey (Fredericton, 1947). N.B., Dept. of Education, Annual report of the schools of New Brunswick (Fredericton), 1885. “Obituary,” Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada ([Toronto]), 5 (1940–42). “Professor of natural history and geology,” Univ. Monthly (Fredericton), 27 (1907), no.1: 16–17. Rayburn, Geog. names of N.B. The register: being a list of former students and graduates of the College of New Brunswick, later King’s College and since 1859, the University of New Brunswick (Fredericton, 1924). “Salmon angling, a never-failing fountain of youth,” comp. R. P. Allen, Maritime Advocate and Busy East (Sackville, N.B.), 33 (1942–43), no.7: 5–7, 28–29. “School and college,” Educational Rev. (Saint John), 20 (1906–7): 279–80. Univ. of N.B., Calendar (Fredericton).

Cite This Article

W. D. Hamilton, “COX, PHILIP,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cox_philip_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cox_philip_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. D. Hamilton |

| Title of Article: | COX, PHILIP |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |