As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

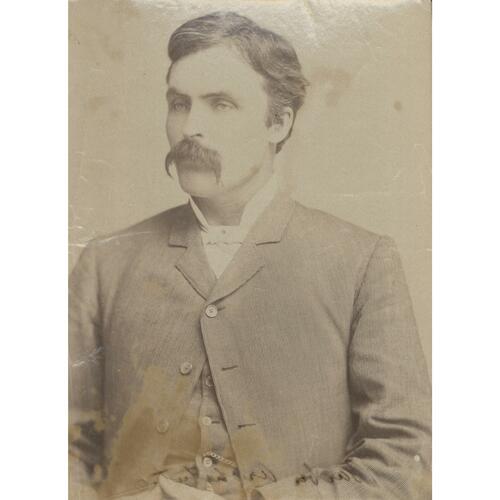

![Barber, Architect [Charles Arnold Barber] - City of Winnipeg Archives Original title: Barber, Architect [Charles Arnold Barber] - City of Winnipeg Archives](/bioimages/w600.12372.jpg)

Source: Link

BARBER, CHARLES ARNOLD, architect, inventor, and convicted extortionist; b. 9 July 1848 in Irish Creek (Jasper), Upper Canada, son of William Barber, a farmer and mason, and Maria Dunn; m. 20 Feb. 1878 Sarah C. Allison in Tyendinaga Township, Ont., and they had two sons and five daughters; d. 22 Sept. 1915 in New Westminster, B.C.

The second of nine children born to his parents, both immigrants from Ireland, Charles Barber reportedly served a five-year apprenticeship with a firm of architects and builders in Rome, N.Y, probably during 1865–70. He later stated that he had established an architectural practice in 1870. That year he formed a partnership in Ottawa and began construction of a business block. Before the work was completed, Barber left Ottawa, abandoning his partner. For the next five years, he subsequently claimed, he “had the superintendency of large railway works and several of the finest buildings in the [United] States and Canada.”

Barber arrived in Winnipeg on 19 May 1876, “principally for his health,” and did not commence advertising his practice until early September. His first known commissions in Winnipeg were the designs for Central and North Ward schools (1876–77), two Italianate structures, the first in Manitoba. His firm also supplied designs for the South Ward (or Carlton Street) School in 1880–81 and an addition to it in 1882, the Ward 5 (or Pinkham) School in 1883, and the Mulvey School in 1884. The association between Barber and the Winnipeg Protestant Board of School Trustees ended in 1884, when, during his supervision of a construction site, Barber was accused of colluding with his brother Isaac, a builder. Barber sued for libel, but the case was dismissed when the charges were withdrawn.

Another early design helped Barber secure contracts with the Church of England in Manitoba. His plans for the St John’s College Ladies’ School (1877) combined the Gothic elements favoured by Anglicans with a mansard roof in the Second Empire style. As a result of the success of this handsome brick structure, his firm was awarded the contracts for the parish school at St James (1881) and St John’s College and deanery (1883). The college was to have been a large, L-shaped complex with several high towers, executed in the Gothic style. Only a small portion was built, because the college’s governing body ran out of money.

Barber also executed a number of designs for local Presbyterians. Although his plans for Knox Presbyterian Church (1878–79) were rejected in favour of those of Balston C. Kenway and Thomas Parr, he supplied the design for Manitoba College (1881–82). His plan combined Romanesque, Second Empire, and Gothic elements to create a flamboyant structure. More conservatively styled was his new Knox Presbyterian Church (1883–84), which featured a large, central auditorium, together with Gothic windows, and towers. Both buildings were landmarks for several decades.

Another unusual design was the one he conceived for Winnipeg’s city hall (1883–86). His earlier civic works had included the town hall in Emerson (1881) and the Winnipeg police station (1883). Whereas the Emerson building was of an elegant Italianate design, and the police station combined Second Empire and Romanesque features, the Winnipeg city hall proved to be almost beyond architectural description. It featured a boxy mass topped by a large cupola, surrounded by four smaller towers at each corner of the building. With its red brick and white stone walls and its copper roof, the city hall was an extraordinary sight. Its oddity made it a readily identifiable symbol of Winnipeg.

The city hall project also marked the downfall of Barber’s architectural firm in Winnipeg. His first partner had been James R. Bowes, who stayed with him under the name of Barber and Bowes from February 1881 to March 1882, when he was replaced by Charles’s younger brother Earl William Barber. As Barber and Barber, the firm became, in 1883, the largest and busiest architectural practice in Winnipeg, with six draftsmen. Yet by 1884 Barber had acquired a somewhat unsavoury reputation. In 1882 it was alleged that a group within the board of directors of the Winnipeg General Hospital, led by Barber, was attempting to take control of the board in order to promote the use of his firm’s plans for new hospital buildings. The attempt was thwarted when directors opposed to the idea were elected. A year later, during construction of the Winnipeg police station, it was claimed that the Barbers were in collusion with the builder, David Kilpatrick. The accusation was never proved. Suspicion was augmented by the charges of complicity made in the summer of 1884, during the construction of the Mulvey School. At the same time the firm was being accused of collusion with the contractor for the construction of the city hall, Robert Dewar. The matter developed into a civic scandal in the autumn of 1884, and the Barbers were dismissed from the city hall project, although they were later exonerated.

By 1885 Winnipeggers considered their city to be a sophisticated urban centre quite finished with such youthful boom-town exuberances as Barber and Barber’s highly ornamental buildings. As a result, the firm designed no structures during 1885 and 1886. The following year only five inconsequential buildings were commissioned. After the federal election of February 1887 Barber was arrested on a charge of bribing a voter to cast his ballot in favour of Conservative candidate William Bain Scarth*. The arrest did much to push him into leaving Winnipeg the following autumn, although the charges had been quietly dropped during the summer. Charles and his brothers Earl and Ernest transferred the business to Duluth, Minn., from where they established branch offices in Superior and Ashland, Wis., as well as in Marquette, Mich. In 1892 Charles Barber reopened his practice in Winnipeg and designed a number of structures, including a plain but substantial building for Nicholas Bawlf on Princess Street to house the Winnipeg Grain and Produce Exchange. It had the then unusual feature of a second-storey truss which produced a 65-foot wide, column-free space on the first storey. Unfortunately, during the depression which started in 1893, Barber found little work in Winnipeg. By then, younger, better-educated architects with cleaner reputations, such as George Browne* Jr, dominated the scene.

Barber and Barber designed their last buildings in Manitoba during 1898. These were the extensive McIntyre Block in Winnipeg [see Alexander McIntyre*] and the public school at Gladstone. The McIntyre Block, the second to have that name, featured a wooden interior framework at a time when steel frames were coming into vogue. It possessed a handsome stone front and a stepped cornice, however, which made it immediately recognizable. The block was a fitting end to a career which had witnessed the creation of so many individualistic buildings. During the period 1876–98, Barber’s firm had produced 106 designs in Manitoba, 85 of which were built.

After 1897 Barber turned his hand to inventing various devices, including a water and ice boat, fire-door, fireproof door, and safe. In the autumn of 1901 he and his wife moved to Montreal, where he carried on a business selling his fireproof door and safe. By 1903 he was manager of the Canada Automatic Fireproof Door and Shutter Company. In late April that year he and his wife were arrested on charges of extortion with violence, committed against a wealthy wholesale grocer, Delphis-Camille Brosseau. During their trial, it was alleged that the Barbers had attempted the same type of extortion in Portage la Prairie, Man., in 1892 and in Niagara Falls, Ont., in 1901. The Barbers were also suspected of similar crimes on a circuit from Chicago to Duluth and St Louis, Mo. Barber was sentenced to seven years in jail, his wife to three. After their release, they were reunited and lived with their son Horace Greeley Barber, first in Calgary and then in Vancouver. Charles Barber died in New Westminster.

Barber was a large man, standing six feet four inches, with a heavy build and red hair. He had been, for a time, a temperance advocate and in Winnipeg he had helped found the United Temperance Benevolent and Literary Association in 1877. Although he was a competent architect with several Manitoba landmarks to his credit, he possessed a dishonest streak which may have manifested itself as early as 1870 in Ottawa. A rival architect, William Critchlow Harris, correctly observed that Barber was “an artist truly whose canvas is that of cunning and whose tools are those of deception.” Dishonest people were a part of boom towns such as Winnipeg and, like more honest individuals, they made contributions to the establishment of communities. Barber’s many architectural designs, gaudy as they often were, shaped Winnipeg’s appearance for many decades.

AO, RG 80-5-0-72, no.3579. B.C., Ministry of Health (Victoria), Vital statistics, death certificate. City of Winnipeg, Arch. and records control branch, City Council, communications, 1876, no.0981; 1892, no.2121. Holy Trinity Anglican Church (Winnipeg), RBMB, nos.1–6. NA, RG 31, C1, 1851, 1861, 1871, Bastard Township, Ont. Chicago Commercial Advertiser, 30 Aug. 1877. Daily Manitoban (Winnipeg), 9 Aug. 1886. Manitoba Free Press, 20 May, 4 Sept., 12 Oct., 13 Nov. 1876; 17 Feb., 2 May 1877; 9 March, 1, 21 May 1878; 21 Feb. 1880; 15 Aug. 1881; 26, 30 May, 4 Sept. 1882; 7, 24 May, 12 June 1883; 31 July 1884; 8 Oct. 1892; 17 Feb. 1893; 17 Dec. 1901. Montreal Daily Star, 30 April, 1 May, 8–12, 15–16 June 1903. Winnipeg Daily Sun, 14 Feb. 1882; 10 May, 10 July, 8 Sept. 1883; 6 May 1884; 22 Feb., 23 March 1887. Winnipeg Daily, Times, 7, 12 March 1881; 3 Feb., 15 Oct. 1883; 7 March, 13 Aug., 14 Oct., 13 Dec. 1884. Winnipeg Telegram, 9 May 1903, 29 Nov. 1915. Winnipeg Tribune, 17 Jan. 1880, 1 May 1903. G. B. Brooks, Plain facts about the new city hall; its inside history from the first down to the present; interesting disclosures (Winnipeg, 1884). Canadian Patent Office Record (Montreal; Ottawa), 27 (1897), no.55241; 29 (1899), no.62725; 32 (1902), no.75809; 33 (1903), no.78971. Directory, Montreal, 1902–3.

Cite This Article

Randy R. Rostecki, “BARBER, CHARLES ARNOLD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barber_charles_arnold_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barber_charles_arnold_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Randy R. Rostecki |

| Title of Article: | BARBER, CHARLES ARNOLD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |