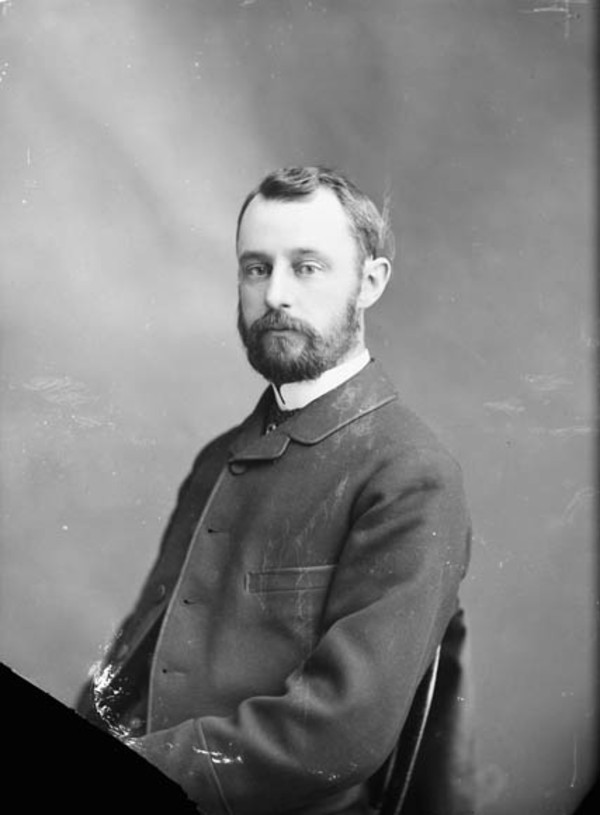

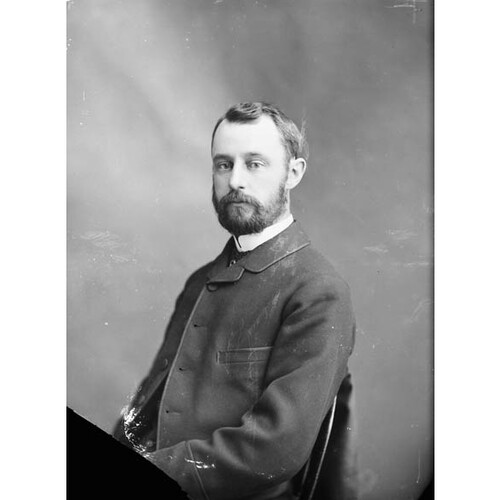

STAIRS, JOHN FITZWILLIAM, industrialist, financier, and politician; b. 19 Jan. 1848 in Halifax, second child of William James Stairs and Susan (Susanna) Duffus Morrow; m. first 27 April 1870 Charlotte Jane Fogo in Halifax, and they had seven children; m. secondly 14 Aug. 1895 Helen Eliza Gaherty, née Bell, in Almonte, Ont., and they had one daughter; d. 26 Sept. 1904 in Toronto.

John Fitzwilliam Stairs was born into a family on the verge of prominence within Halifax’s mercantile élite. His grandfather William Machin Stairs* was founder and principal of a hardware and ship chandlery firm, and his father was a partner. After the death of his eldest son in 1860, W. J. Stairs focused his hopes and ambitions on John Fitzwilliam. Young Stairs was educated at the Reverend James Woods’s school and Dalhousie College, attending the latter as an “occasional student” from 1865 to 1867. On reaching his majority in 1869 he became a partner in the family firm of William Stairs, Son and Morrow and was appointed manager of the Dartmouth Rope Works, an ambitious venture which his father had established that year to supply cordage to the department of the firm selling ship chandlery, ships’ outfits, and fishery goods.

The rope-works was a self-contained industrial community. In addition to an oakum factory, it had housing for employees, a building which served as a school on weekdays and a church on Sundays, and the longest structure in the province, a 1,200-foot rope-walk, at one end of which stood the manager’s residence, which still survives. The works flourished under Stairs’s paternalistic direction, and by the mid 1870s it was described as “the most extensive and complete” manufacturing complex of its kind in the country. It not only supplied the local market and carried on a thriving export trade with Britain and Europe, but it also led the continent in the production of binder twine. After the erection in 1883 of a factory purpose-built for manufacturing binder twine, the latter gradually replaced cordage as the most marketable product, and the works came to have a virtual monopoly on twine in Canada. Credit for turning the rope-works into the most successful one in the country belongs to Stairs, whose skills as an industrial manager it showed perfectly. In 1890 Stairs became president of the Consumers’ Cordage Company Limited, a Montreal-based combine which brought together the seven largest rope-manufacturing firms in Canada; the management of the Dartmouth Rope Works devolved on his brother George, a fellow director of Consumers’. Ownership of the works by the Stairs family firm ended in 1892 when it was purchased by Consumers’.

The success of the works was responsible for the development of the north end of Dartmouth, and it also launched Stairs’s political career. In 1877 he became alderman for Dartmouth’s Ward 3, which comprehended the north end. He served two one-year terms and in the election of 1879 lost by two votes to the incumbent warden. A Conservative like his father and an enthusiastic advocate of the system of protective tariffs introduced by the National Policy [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*], particularly because of the potential benefits of that policy to his company, Stairs entered the Nova Scotia House of Assembly in a by-election for Halifax County in November 1879. Within a month he had been appointed minister without portfolio in the cabinet of Simon Hugh Holmes*. When the ministry dissolved in May 1882 after Holmes’s resignation, Stairs declined to serve under the new premier, Attorney General John Sparrow David Thompson*. As a close associate of Holmes, he chose to follow him into retirement. Perhaps, too, he had seen the writing on the wall, since the government was defeated in the election of that year. In 1883 Stairs stood unopposed for warden of Dartmouth. He was elected to a second one-year term in 1884 but did not offer in 1885.

The rope-works provided Stairs with capital to invest in other manufacturing industries. His first, and in the event his most far-reaching, involvement was in steel making. In 1882 the Nova Scotia Steel Company was formed at New Glasgow by Graham Fraser* and George Forrest McKay to make steel and steel products. Stairs owned nearly four per cent of the stock, and a similar portion was subscribed by William Stairs, Son and Morrow. As a director of the company and its successors for 22 years, Stairs was the driving force behind the acquisitions, expansions, mergers, and recapitalizations which culminated in 1901 in the organization of the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company Limited. His involvement also represented, in the words of historian T. W. Acheson, “one of the few examples of inter-community industrial activity in this period” in the Maritimes.

Stairs’s entry into federal politics in 1883 had been engineered by Sir Charles Tupper*, the leader of the federal Conservatives in Nova Scotia, who held Stairs’s father in the highest esteem. The appointment of Matthew Henry Richey as lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia created a vacancy in the House of Commons for Halifax, and Stairs received the Conservative nomination. Because the Conservatives had taken both Halifax seats at the general election the previous year, the Liberals did not bother to field a candidate and Stairs was returned by acclamation. As a protégé of Tupper, Stairs rapidly became intimate and influential with Sir John A. Macdonald*. He urged the prime minister in 1885 to invite Thompson to join the cabinet after he himself had apparently declined a position. Although Stairs spoke infrequently in parliament and did not distinguish himself in debate, he was an excellent committee man.

Stairs’s shortcomings as a constituency politician were revealed when he faced the electorate for the first time in the general election of 1887. Relatively unknown by the voters, he conducted a poor campaign, and he was hampered by the manifesto of the Conservatives, based on the National Policy, which made no attempt to address the needs of the farmers and fishermen in the riding. The result was that he lost to the Liberal Alfred Gilpin Jones, a relation by marriage.

At the general election of 1891 the return of Tupper from Britain, where he had been Canadian high commissioner, guaranteed that Stairs would reoffer in Halifax. Rural electors, fearful of the Liberal platform of unrestricted reciprocity, forgot their resentment that the National Policy chiefly benefited the industrial urban classes and helped Stairs to defeat Jones by 927 votes. Stairs and his colleague, Thomas Edward Kenny, were, however, charged by Jones and his running mate, Edward Farrell, with bribery and other illegal acts, and although they were cleared of personal involvement the election was declared void. Kenny and Stairs were victorious in the by-election of February 1892, but their majorities were reduced by more than half.

The fact that Halifax began to develop as a centre for industrial finance during Stairs’s second term as an mp was not a coincidence, since he aggressively exploited his position to serve his business career. He had worked behind the scenes to overcome parliamentary opposition to the formation of Consumers’ Cordage, and in 1893 he procured a federal act of incorporation for the Eastern Trust Company, of which he was president and his father the principal shareholder. An example of a new kind of financial intermediary in Canada, Eastern Trust was organized with the support of the Union Bank of Halifax as a quasi-industrial development bank. Not surprisingly, it helped recapitalize Nova Scotia Steel, for which it also acted as a trustee for bond holders and a registrar of bonds. In addition, Stairs introduced bills of incorporation for new manufacturing companies in the Maritimes and for regional mergers, and he used his influence to help impose or substantially increase tariffs protective of Maritime manufacturing companies, especially those in which he was involved. He was less successful in obtaining preferential freight rates on the Intercolonial Railway that would enable manufacturers in the Maritimes to compete in central Canadian markets.

Stairs did not reoffer in the general election of 1896. His reasons for standing down in favour of Robert Laird Borden* are obscure. The received account is that he was intending to move to Montreal because of business interests, but his sojourn there was brief and he resumed his provincial political career the following year. If the intention was that Borden would be a locum tenens for one term, by its end Stairs had become too involved in provincial politics to resume his career in Ottawa and Borden had been chosen leader of the federal Conservatives.

After the defeat of the federal Conservatives in 1896, Tupper went to Nova Scotia to reorganize the provincial party and prepare it for a general election; when in October a Liberal-Conservative Union on the British model was established, Stairs became president and de facto leader of the party. The 1897 election was a disaster for the Conservatives: they returned only three candidates, Stairs finishing fifth of six in Halifax County. He had been savaged by the Liberal Morning Chronicle of Halifax, which claimed that he supported protective tariffs because of personal interest, and his reputation as a monopolist and corporate wheeler-dealer undoubtedly also hurt his electoral chances.

Stairs gamely continued as leader, but in the general election of 1901 the Conservatives were reduced to two mhas. He had stood in Colchester County, where he finished last of four, although the race was very close. Preoccupied with improving his chances of winning, Stairs had not bothered to issue an election manifesto and had left the management of the campaign largely to Charles Hazlitt Cahan*, a former Conservative house leader and close business associate. Despite his second consecutive defeat, he did not step down as leader, and in March 1904 he became president of the newly formed Liberal-Conservative Association of Nova Scotia. Ever the optimist, Stairs told the press that he had never seen the party in better shape in Nova Scotia. He did not live to witness the annihilation of the Conservatives in the federal election of November.

It is doubtful whether greater efforts by Stairs after 1896 would have improved the fortunes of the Conservatives, since the province was enjoying good economic times, the Liberals had given “a highly creditable government performance,” and the former Liberal premier William Stevens Fielding* was federal minister of finance. Notwithstanding his lack of success, however, Stairs was well thought of in the party. He was unique among Nova Scotia Conservatives of the late 19th century in voluntarily renouncing a successful career in Ottawa in order to enter the uncertain realm of provincial politics. His failure to revive the provincial party was more than balanced by his aid in giving birth to the careers in federal politics of Thompson and Borden.

If by the late 1890s Stairs was politically a spent force, his business career was flourishing as never before. A director of the Nova Scotia Sugar Refinery Limited of Halifax since 1886, he arranged a merger of the refinery, the Halifax Sugar Refinery Limited of Woodside (Dartmouth) [see George Gordon Dustan], and the Moncton Sugar Refining Company [see John Leonard Harris*] on behalf of a Scottish syndicate aiming to consolidate the Maritime sugar-refining industry. The result was the launching of the Acadia Sugar Refining Company Limited in August 1893. Stairs became president of the new combine, which was registered in England because he was unable to have it incorporated in Nova Scotia. It is likely that Eastern Trust was founded in order to ensure the successful flotation of Acadia, since the latter’s assets were mortgaged to Eastern Trust to underwrite the bond issue.

In 1895 Stairs became vice-president of the Nova Scotia Iron and Steel Company, formed by the amalgamation of the Nova Scotia Steel and Forge Company, successor to the Nova Scotia Steel Company, and the New Glasgow Iron, Coal and Railway Company, whose successful flotation in 1891 he had helped achieve. The amalgamation was in line with his belief that the firm could expand its share of the market by combining all aspects of production and marketing within one asset base and exploiting fragmentation among its competitors. In 1897 Stairs replaced Graham Fraser as president of Nova Scotia Iron and Steel, and he became president of its successor, Nova Scotia Steel and Coal, when it was created in 1901. His innovative techniques, including manipulation of the stock market in order to raise investment capital, helped Nova Scotia Steel and Coal show the largest operations in the history of Nova Scotia steel making during the fiscal year of 1903–4, the last full year of his presidency.

Other regional manufacturing concerns in which Stairs was interested were the Robb Engineering Company Limited of Amherst, N.S., of which he became a director, and the Alexander Gibson Railway and Manufacturing Company of Marysville (Fredericton) [see Alexander Gibson*], which he attempted to reorganize in 1902 and of which he also became a director. Stairs did not invest in either company, and it is possible that he got involved because the other directors believed that his name on their letterhead would attract potential investors.

During the last three years of his life Stairs entered competitively into banking, an area new to him. No eastern Canadian financier recognized more clearly that “having [Maritime banks] absorbed by [central Canadian] institutions creates a likelihood of our interests being sacrificed” to those of central Canada, and that the only way to maintain local control of Maritime banks was to amalgamate them in a single institution capable of resisting absorption by central Canadian interests. He did not, however, pretend that such a pan-Maritime bank could compete on an equal footing with banks in central Canada; his chief goals were to reduce the unhealthy competition caused by the large number of Maritime banks and ensure that regional corporate mergers were financed by a single regional investment bank.

Using as a base the Union Bank of Halifax, of which the Stairs family and their family business were the largest shareholders and Nova Scotia Steel the largest depositor, Stairs developed and began to implement a bold plan to create a pan-Maritime bank by merging smaller banks with the Union. His first acquisition was the Commercial Bank of Windsor, which the Union Bank purchased in 1902. The sale was negotiated by the young, self-styled promoter William Maxwell Aitken*. The precise circumstances of the meeting of the two men are unknown, but it appears that Aitken introduced himself out of the blue and asked Stairs for a job and that Stairs was sufficiently impressed to offer him one. Aitken was soon ensconced as executive assistant to Stairs, who began to treat him like an adopted son.

The Commercial Bank transaction earned Aitken $10,000, which he invested in a new company, Royal Securities Corporation Limited, the first agency east of Montreal for retailing stocks and bonds. Royal Securities, of which Stairs became president and Aitken secretary and general manager, opened for business in the spring of 1903. Operating in an area where, unlike banking, little or no competition existed, Royal Securities soon developed into an investment bank which helped finance the local manufacturing industry and specialized in Central American and West Indian public utilities. Among the earliest and most successful of the latter was the Trinidad Electric Company. This company had commenced operations in 1901 with Stairs as president, and its success had been partly responsible for Stairs’s decision to establish Royal Securities.

Stairs’s next objective was the People’s Bank of Halifax. In April 1903 he and “his most intimate friend,” Robert Edward Harris*, a Halifax corporate lawyer, bought 18 per cent of the stock of the bank, becoming the largest shareholders. In response to the initiative, the bank’s capital stock rose from $700,000 to $1,000,000. But the increase was artificial: the directors (chief of whom was the president, John James Stewart) and the general manager had concealed a fraud which would have caused the bank to fail because they were anxious to obtain the increase in stock and the prestige conferred on the bank by Stairs becoming a shareholder. If Aitken, George Stairs, and Royal Securities had not assumed Stairs’s liability soon after his death, his relatively modest personal estate of some $238,000 would have been exhausted when the fraud was discovered.

Although Stairs denied that he was attempting to acquire control of the People’s Bank when he purchased the stock, he intended to merge it in the national bank he was organizing. In June 1903 he headed a Halifax syndicate which petitioned parliament for an act of incorporation for the Alliance Bank of Canada. The legislation was passed on 24 October. Capitalized at $5,000,000, the new bank reportedly made “substantial progress toward organization.” Difficulties over financing, however, prevented the Alliance from applying to the Treasury Board for a certificate authorizing it to commence business within the statutory one-year period of grace, and Stairs and the provisional directors petitioned parliament for an act which would allow them an extension of nine months.

Such an act was passed on 10 Aug. 1904. Ten days or so later, Stairs and Aitken went to Toronto, ostensibly to arrange underwriting for the new bond issue by Nova Scotia Steel and Coal, but in reality to borrow money in order to finance the acquisition of the People’s Bank by the Union Bank and to start up the Alliance. Stairs caught a cold which turned to pneumonia, and he was taken to hospital on 9 September. Although he was expected to recover, 17 days later he died of heart disease, complicated by kidney failure and pneumonia. The Alliance Bank expired with him, as did any hope of Halifax remaining the eastern Canadian centre of high finance.

Stairs’s death came as a surprise to everyone, but he had been unwell for some time, suffering from lumbago and general decline, and colleagues had commented on how poorly he looked. The last photographs of him reveal a man frail and prematurely aged, and even he had accepted the necessity of a long vacation. His body was conveyed to Halifax, where he was given an imposing funeral.

Stairs had been scarcely less prominent in church and community affairs than in the business world. A pillar of Fort Massey Presbyterian Church in Halifax, where he was superintendent of the Sunday school from 1888 to 1894 and again from 1896, and of which he was elected an elder in 1903, he was president of the Nova Scotia Sunday School Association at the time of his death. He had been appointed a member of the board of governors of Dalhousie in 1893, and he was elected chairman in 1899. Stairs was an enthusiastic advocate of advanced technical education, which he believed would arrest the migration of talent to Ontario, and the School of Mines was inaugurated at Dalhousie in 1902 almost entirely because of his efforts. After his death the idea of a chair in his name at Dalhousie was suggested. Although the chair did not materialize, a memorial stained-glass window was placed in Fort Massey Church by his widow and children in 1909.

The most conspicuously successful promoter of mergers and financial intermediary in turn-of-the-century Nova Scotia, Stairs was also a major figure in the transition from industrial to finance capitalism, as evidenced by his creation of Royal Securities, an institution of a type then unknown in Canada. As the leading corporate financier in the Maritimes, he was innovative and aggressively competitive but also courageous, far-seeing, and optimistic, believing that Maritime manufacturing industries could compete successfully with central Canadian firms if they had equal access to markets through rail links and winter ports. Adept at marshalling and manipulating capital, he did not hesitate to raise money in Montreal, Toronto, and overseas. And although Stairs was a businessman first and a politician second, by becoming an important regional politician he was better able than pure businessmen to influence a potentially hostile economic environment.

Stairs was twice married. His first wife died of diphtheria in 1886, and in 1895 he married a 32-year-old widow, Mrs Helen Eliza Gaherty, to whom he had almost certainly been introduced through his fellow mp Bennett Rosamond. Stairs appears to have named the only child of his second marriage after Rosamond’s mother. He was survived by six of his eight children and his wife, who died in 1963 in her hundredth year.

[The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Dr Gregory P. Marchildon of the Center of Canadian Studies at the Johns Hopkins Univ. School of Advanced International Studies, Washington, who allowed him to consult the manuscript of his article “John F. Stairs, Max Aitken and the Scotia Group: finance capitalism and industrial decline in the Maritimes, 1890–1914,” now published in Farm, factory and fortune: new studies in the economic history of the Maritime provinces, ed. Kris Inwood (Fredericton, 1993).

The John F. Stairs archive, currently held by his daughter Mrs Margaret Stairs Budden of Toronto, is valuable though not extensive. It includes a scrapbook of obituaries of the subject collected by his widow, Mrs Helen Bell Stairs. Stairs’s correspondence with Sir John A. Macdonald, 1883–91, Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*, 1891, Sir John S. D. Thompson, 1880–84, and Sir Charles Tupper, 1887 and 1898–99, is in their papers at the NA (MG 26, A; C; D; F). The Beaverbrook papers at the House of Lords Record Office, London, contain no pre-1903 correspondence with Stairs, and Beaverbrook appears to have destroyed his diaries for 1904 and 1905 and any 1904 Stairs correspondence.

Four letters written by the subject to his mother in 1861 while he was travelling in the United States at the start of the American Civil War have been published as “A report from our man in Savannah,” Atlantic Advocate, 54 (1963–64), no.5: 59–60. The original letters, and an accompanying 1858 photograph of Stairs, are in the Stairs archive in the custody of Mrs Budden. j.b.c.]

Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), Estate papers, no.5974. House of Lords Record Office, Beaverbrook papers, ser.A, 12–19; ser.G1. PANS, MG 1, 167–70, 3197–200. T. W. Acheson, “The National Policy and the industrialization of the Maritimes, 1880–1910,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 1 (1971–72), no.2: 1–28; “The social origins of Canadian industrialism: a study in the structure of entrepreneurship” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1971). [W. M. Aitken, 1st Baron] Beaverbrook, My early life (Fredericton, 1965). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1884–87, 1892–96; Journals, 1903–4; Parl., Sessional papers, 1891–1905; Statutes, 1893–1904. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1901–4. Anne Chisholm and Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: a life (London, 1992). CPG, 1880–96. Dominion annual reg., 1879–83. J. D. Frost, “The business and political careers of John F. Stairs of Halifax, 1879–1891” (ba honours essay, Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, 1976). G. P. Marchildon, “Promotion finance and mergers in the Canadian manufacturing industry, 1885–1918” (phd thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, Univ. of London, 1990). N.S., Statutes, 1888–1901. Nova Scotia Steel Company, Reports of directors and financial statements, 1883–1910 (bound coll. in PANS, Library). A. J. P. Taylor, Beaverbrook (London, 1972). Waite, Man from Halifax.

Cite This Article

J. B. Cahill, “STAIRS, JOHN FITZWILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stairs_john_fitzwilliam_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stairs_john_fitzwilliam_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. B. Cahill |

| Title of Article: | STAIRS, JOHN FITZWILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |